Hügelkultur

.jpg)

Hügelkultur is a composting process employing raised beds constructed from decaying wood debris and other compostable biomass plant materials. The process helps to improve soil fertility, water retention, and soil warming, thus benefiting plants grown on or near such mounds.[1][2]

Description

.jpg)

Hügelkultur replicates the natural process of decomposition that occurs on forest floors. Trees that fall in a forest often become nurse logs[3] decaying and providing ecological facilitation to seedlings. As the wood decays, its porosity increases allowing it to store water "like a sponge". The water is slowly released back into the environment, benefiting nearby plants.[1]

Mounded hügelkultur beds are ideal for areas where the underlying soil is of poor quality or compacted. They tend to be easier to maintain due to their relative height above the ground.[3] The beds are usually about 3 feet (0.91 m) by 6 feet (1.8 m) in area and about 3 feet (0.91 m) high.[1]

History

Hügelkultur is a German word meaning mound culture or hill culture.[4] It was practiced in German and Eastern European societies for hundreds of years,[1][5] before being further developed by Sepp Holzer, an Austrian permaculture expert.[3] In addition, recent permaculture voices such as Paul Wheaton and Geoff Lawton advocate strongly for Hügelkultur beds as a perfect permaculture design.[6]

Construction

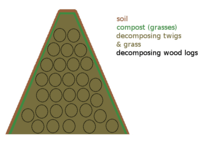

In its basic form, mounds are constructed by piling logs, branches, plant waste, compost and additional soil directly on the ground. The pile has the form of a pyramid, and is about 1.5 m high. The sides of the two slopes both have a grade of between 65 and 80 degrees.[7]

When positioned on sloped terrain, the beds need to be put at an angle to the hillside (rather than having them parallel to it). This makes sure the beds do not receive unequal amounts of water. In most cases, it's also useful to have the beds positioned against the prevailing wind direction.

The raised bed can form light-duty swales, circles and mazes.[8][9] Mounds may also be made from alternating layers of wood, sod,[10] compost, straw, and soil. Although their construction is straightforward, planning is necessary to prevent steep slopes that would result in erosion.[3][5]

Anything can be grown on the raised beds, yet if the raised bed will decompose/release its nutrients quickly (so is not made of bulky materials like tree trunks), more demanding crops such as pumpkins, courgettes, cucumbers, cabbages, tomatoes, sweet corn, celery, potatoes are grown in the first year, after which the bed is used for less demanding crops like beans, peas, and strawberries.

In his book Desert or Paradise: Restoring Endangered Landscapes Using Water Management, Including Lake and Pond Construction, Holzer describes a method of constructing Hügelkultur including a design that incorporates rubbish such as cardboard, clothes and kitchen waste. He recommends building mounds that are 1 meter (3.3 ft) wide and any length. Mounds are built in a 0.7 meters (2.3 ft) trench in sandy soil, and without a trench if the ground is wet.[7]

Danger in mistaking Hügelkultur mounds for solid earthworks

Although hügelkulture beds can safely retain water in light-duty applications (for example, conserving the moisture of rain that falls on the bed), creating heavy-duty rainwater retention areas behind hügelkulture beds on contour, to catch surface runoff from surrounding areas, can be dangerous. Some designers conflate the hügelkultur bed's appearance with that of solid earthworks, but hügelkultur beds cannot predictably control large amounts of stormwater in the way that solid earthworks can. Whereas embankment dams or the hillsides of swales can be relied on to hold back many thousands of gallons of water for weeks to allow it to seep into the ground, and berms can slow runoff, hügelkultur beds are different in two ways: earthworks have no buoyant core (whereas hügelkultur mounds contain logs), and the soil that they are made of is compacted. If fresh or dried timber is used in the bed, it may become buoyant in the water-saturated substrate, bursting from the soil covering and releasing all the sitting water through a breach. This can be an issue for years, until the wood is sufficiently rotten and infused with water. Another consideration is that hügelkultur beds will degrade, shrinking over time into much lower mounds of soft, rich soil. This means that the retention area will have less depth as time goes on, but it also means that the uncompacted soil will remain a threat to breaching even if the logs become saturated.

There is a recorded instance of a breach occurring in a new project. Upon the first rainstorm, the retention areas behind the hügelkultur beds filled with water and broke through. The released water carried the freshly-buried logs and dirt downhill, smashing a hole in a building being used as a church and filling the space with mud. No injuries were reported.[11]

Some permaculturists have taken mild positions against the "hügel swales" still being promoted by other permaculturists, citing the danger and cross-purposes of hügelkultur beds and swales.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 Miles, Melissa (August 3, 2010). "The Art and Science of Making a Hugelkultur Bed – Transforming Woody Debris into a Garden Resource". The Permaculture Research Institute. Retrieved May 2, 2014.

- ↑ "The Many Benefits of Hugelkultur". Permaculture Magazine. October 17, 2013. Retrieved May 2, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 Palmer, Kim (August 14, 2013). "A Garden Made of WOOD; Hugelkultur (Hooogellocullocher or Hewogellocullocher) A Nature-Inspired Method of Gardening in Beds Built on Logs, Touted as a Drought-Resistant Way to Produce Food". Minneapolis, MN. Star Tribune. Retrieved May 2, 2014.

- ↑ Lauterbach, Margaret (February 2, 2012). "Margaret Lauterbach: Clippings fuel fertile 'hugel' mounds". Boise, ID. Idaho Statesman. Retrieved May 3, 2014.

- 1 2 Martin, Claire (April 11, 2014). "Hugelkultur , translated: A path to richer soil". Denver, CO. Denver Post. Retrieved May 2, 2014.

- ↑ Wheaton, Paul, hugelkultur: the ultimate raised garden beds, retrieved 6/9/2014

- 1 2 Holzer, Sepp (2012). Hügelkultur. Chelsea Green Publishing. pp. 131–134, 139. ISBN 978-1603584647.

- ↑ Hemenway, Toby (2009). Gaia's Garden: A Guide to Home-Scale Permaculture. Chelsea Green Publishing. pp. 84–85. ISBN 9781603582230.

- ↑ Feineigle, Mark (January 4, 2012). "Hugelkultur: Composting Whole Trees With Ease". The Permaculture Research Institute. Retrieved May 2, 2014.

- ↑ Shein, Christopher (2013). The Vegetable Gardener's Guide to Permaculture: Creating an Edible Ecosystem. Timber Press. p. 28. ISBN 978-1604692709.

- ↑ Spirko, Jack (November 6, 2015). "Don't Try Building Hugel Swales". permaculturenews.org. Retrieved March 17, 2016.

External links

| Look up hügelkultur in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Hugelkultur: The Ultimate Raised Garden Beds by Paul Wheaton

- Hugelkultur Video

- hugelkultur forum on Hugelkultur at permies.com