Huancavelica

| Huancavelica | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| City | |||

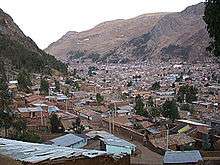

|

Panorama of the city | |||

| |||

| Nickname(s): "Villa Rica de Oropesa" | |||

Huancavelica Location of the city of Huancavelica in Peru | |||

| Coordinates: 12°47′11″S 74°58′32″W / 12.78639°S 74.97556°WCoordinates: 12°47′11″S 74°58′32″W / 12.78639°S 74.97556°W | |||

| Country |

| ||

| Region | Huancavelica | ||

| Province | Huancavelica | ||

| Government | |||

| • Mayor | Pedro Manuel Palomino Pastrana | ||

| Area | |||

| • Total | 514.10 km2 (198.50 sq mi) | ||

| Elevation | 3,676 m (12,060 ft) | ||

| Population | |||

| • Estimate (2015)[1] | 47,866 | ||

| Demonym(s) | Huancavelicano(a) | ||

| Time zone | PET (UTC-5) | ||

| • Summer (DST) | PET (UTC-5) | ||

| Website | www.munihuancavelica.gob.pe | ||

Huancavelica (Spanish pronunciation: [waŋkaβeˈlika]) or Wankawilka in Quechua is a city in Peru. It is the capital of the Huancavelica region and according to the 2007 census had a population of 40,004 people (41,334 in the metropolitan area). The city was established on August 5, 1572 by the Viceroy of Peru Francisco de Toledo. Indigenous peoples represent a major percentage of the population. It has an approximate altitude of 3,660 meters; the climate is cold and dry between the months of February and August with a rainy season between September and January. It is considered one of the poorest cities in Peru.

Geography

The Huancavelica area features a rough geography with highly varied elevation, from 1,950 metres in the valleys to more than 5,000 metres on its snow-covered summits. These mountains contain metallic deposits. They consist of the western chain of the Andes, which includes the Chunta mountain range, formed by a series of hills, the most prominent of which are: Sitaq (5,328m), Wamanrasu (5,298m) and Altar (5,268m).

Among the rivers of the region there are the Mantaro, the Pampas, the Huarpa and the Churcampa. The Mantaro River penetrates Huancavelica, forming Tayacaja's Peninsula. Another river that shapes the relief is the Pampas River which is born in the lakes of the high mountains of Huancavelica, Chuqlluqucha and Urququcha.

History

In the pre-Incan era, Huancavelica was known as the Wankawillka region or "the place where the grandsons of the Wankas live". The city itself was established on August 5, 1572.

The deposits of Huancavelica were disclosed in 1564, or 1566, by the Indian Nahuincopa to his master Jerónimo Luis de Cabrera. The Spanish Crown appropriated them in 1570 and operated them until Peruvian independence in 1821. Considered the "greatest jewel in the crown", they eliminated the need to ship mercury from Almadén. A miners guild, Gremio de Mineros, administered the mines from 1577 until 1782. Production stopped from 1813 through 1835. In 1915 E.E. Fernandini took over ownership.[2]

The area was the most prolific source of mercury in Spanish America, and as such was vital to the mining operations of the Spanish colonial era.[2] Mercury was necessary to extract silver from the ores produced in the silver mines of Peru, as well as those of Potosí in Alto Perú ("Upper Perú," now Bolivia), using amalgamation processes such as the patio process or pan amalgamation. Mercury was so essential that mercury consumption was the basis upon which the tax on precious metals, known as the quinto real ("royal fifth"), was levied.

The extraction of the quicksilver in the socavones (tunnels) was extremely difficult. Every day before the miners came down, a mass for the dead was celebrated. Due to the need of numerous hand-workers and the high rate of mortality, the Viceroy of Perù Francisco de Toledo resumed and improved the pre-Columbian mandatory service of the mita. The allotted concession were rectangular, about 67x33m. Miners were divided in carreteros and barreteros.

Due to the discovery and then the extraction of the azogue (mercury) in a hill close to the actual location of the city, the Santa Barbara mine became famous in the new world[2] and its activity led to the Viceroy of Peru, Francisco de Toledo, to establish the city in 1572 with the name of Villa Rica de Oropesa.

In 1648 the Viceroy of Peru, declared that Potosí and Huancavelica were "the two pillars that support this kingdom and that of Spain." Moreover, the viceroy thought that Spain could, if necessary, dispense with the silver from Potosí, but it could not dispense with the mercury from Huancavelica.[3]

In the modern times, due to different political and economical events, the city went through a period of decades of lack of progress from the rest of the country. Now, this situation appears to change due to the attention of the recent government administrations.

A 1977 recording of a wedding song sung by a young girl from this region was included on the Golden Record carried on board the Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 probes.

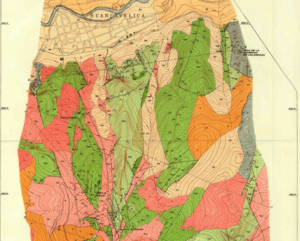

Geology

The principal ore mineral is cinnabar, which occurs within the Cretaceous Gran Farallon sandstones, and fractures found in the Jurassic Pucara and Cretaceous Machay limestones and igneous rocks. Other sulfide minerals occurring with these deposits include pyrite, arsenopyrite and realgar.[2]

Caving became top to bottom in 1806 in order to avoid several disasters in previous years. The most infamous one being the Marroquin caving which took the lives of over a hundred Indians.[2]

Most of the quicksilver was produced from 1571 until 1790, amounting to more than 1,400,000 flasks.[2]

Transportation

Buses run from Huancavelica to Huancayo and Lima by a paved road. There is another road that connects it with the city of Pisco in the coast. Buses depart from the terminal terrestre located in the west side of the city.

Huancavelica is serviced by a train which runs between it and Huancayo known as "el Tren Macho". According to popular saying, this train “leaves when it wants and arrives when it can...”.

In 2009, the line between the break-of-gauge at Huancayo to Huancavelica was being converted from 914 mm (3 ft) gauge to 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) gauge.[4] By October 2010 it was finished and it is now in service.

Education

Huancavelica is home of the local university; the Universidad Nacional de Huancavelica, which has some branches in other cities of the region. The city is home too of other technical institutes like the Instituto Superior Tecnologico and the Instituto Superior Pedagogico.

Health

The city has one hospital; the Hospital General, that serves the city and the nearby towns. Close to the hospital there is a clinic; the Policlinico EsSalud.

Places of interest

The city has monuments from the times of the colony, most of them are churches in a number of eight, located in different parts of the city, of which the most important is the cathedral located at the main square. Another important site is the former Santa Barbara mine, located about three Km. from the city in an ancient road that was famous during colonial times for the extraction of mercury.

See also

- Almadén (the other major source of mercury in the Spanish empire).

- Transport in Peru

References

- ↑ Perú: Población estimada al 30 de junio y tasa de crecimiento de las ciudades capitales, por departamento, 2011 y 2015. Perú: Estimaciones y proyecciones de población total por sexo de las principales ciudades, 2012-2015 (Report). Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática. March 2012. Retrieved 2015-06-03.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Yates, Robert; Kent, Dean; Concha, Jaime (1951). Geology of the Huancavelica Quicksilver District, Peru, USGS Bulletin 975-A. Washington: United States Government Printing Office. pp. 1–45.

- ↑ Arthur Preston Whitaker, The Huancavelica Mercury Mine: A Contribution to the History of the Bourbon Renaissance in the Spanish Empire, Harvard Historical Monographs 16 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1941).

- ↑ Trains (magazine), March 2009, p68

External links

- Pagina Web del Gobierno Regional de Huancavelica - Peru

- Web Oficial Municipalidad de la Ciudad de Huancavelica

- Rutas de Acceso a Huancavelica desde Lima - Peru

Bruno COLLIN, « L’argent du Potosi (Pérou) et les émissions monétaires françaises », Histoire et mesure, XVII - N° 3/4 - Monnaie et espace, mis en ligne le 30 octobre 2006, référence du 24 septembre 2007, disponible sur : http://histoiremesure.revues.org/document894.html.

Raul GUERRERO (Pau University, UA 911), La cartographie minière américaine. http://www.mgm.fr/PUB/Mappemonde/M488/m41_43.pdf

- Web Page of Gobierno Regional de Huancavelica - Peru

- Rutas de Acceso a Huancavelica desde Lima - Peru