Hualapai

|

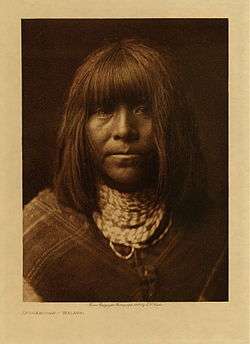

Ta'thamiche, Hualapai | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 2,300 enrolled members | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|

| |

| Languages | |

| Hualapai, English | |

| Religion | |

| Indigenous, Christianity | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Mohave, Yavapai, Havasupai |

The Hualapai (pronounced Wa-la-pie) is a federally recognized Indian tribe in Arizona with over 2300 enrolled members. Approximately 1353 enrolled members reside on the Hualapai Indian reservation, which spans over three counties in Northern Arizona (Coconino, Yavapai, and Mohave).[1]

The name, meaning "people of the tall trees", is derived from hwa:l, the Hualapai word for ponderosa pine[1] and pai “people”. Their traditional territory is a 108-mile (174 km) stretch along the pine-clad southern side of the Grand Canyon and the Colorado River with the tribal capital at Peach Springs.

Government

The Hualapai tribe is a sovereign nation and governed by an executive and judicial branch and a tribal council. The tribe provides a variety of social, cultural, educational and economic services to its members.

Language

The Hualapai language is a Pai branch of the Yuman–Cochimí languages, also spoken by the closely related Havasupai, and more distantly to Yavapai people. It is still spoken by most people over 30 on the Reservation as well as many young people. The Peach Springs School District runs a successful bilingual program for all local students, both Hualapai and non-Hualapai, in addition to immersion camps.

Reservation

The Hualapai Indian Reservation (35°54′25″N 113°07′58″W / 35.90694°N 113.13278°W), covering 1,142 square miles (2,960 km2), was created by the Presidential Executive order of Chester A. Arthur on January 4, 1883.[2]

History and culture

.jpg)

Ceremonies

Major traditional ceremonies of the Hualapai include the "Maturity" ceremony and the "Mourning" ceremony. Nowadays the modern Sobriety Festival is also celebrated in June.

Afterlife

The souls of the dead are believed to go northwestward to a beautiful land where plentiful harvest grow. This land is believed to be seen only by Hualapai spirits.

Traditional dress

Traditional Hualapai dress consists of full suits of deerskin and rabbit skin robes.

Traditional housing

Conical houses formed from cedar boughs using the single slope form called a Wikiup.

Reservation life

The Hualapai Reservation was created by executive order in 1883 on lands that just four regional bands considered as part of their home range, like the Yi Kwat Pa'a (Iquad Ba:' – “Peach Springs band”) or Ha'kasa Pa'a (Hak saha Ba:' - “Pine Springs band”). The other Hualapai regional bands (including the Havasupai) lived far away from the current reservation land. [3]

Hualapai War

The Hualapai War (1865–1870) was caused by an increase in traffic through the area on the Fort Mojave-Prescott Toll Road which elevated tensions and produced armed conflicts between the Hualapai and European Americans. The war broke out in May 1865, when the Hualapai leader Anasa was killed by a man named Hundertinark in the area of Camp Willow Grove and in March 1866. In response, a man named Clower was killed by the Hualapai, who also closed the route from Prescott, Arizona to the Colorado River ports due to the conflict. The most important and principal Hualapai leaders (called Tokoomhet or Tokumhet) at that time were: Wauba Yuba (Wauba Yuma of the Yavapai Fighters subtribe), Sherum (Shrum or Cherum of the Ha Emete Pa'a i.e. “Cerbat Mountain band” of the Middle Mountain People subtribe), Hitchi Hitchi (Hitchie-Hitchie of the Plateau People subtribe)[4] and Susquatama (Sudjikwo'dime, better known by his nickname Hualapai Charley, Hualapai Charlie, Walapai Charley or Walapai Charlie of the Middle Mountain People subtribe). It was not until William Hardy and the Hualapai leaders negotiated a peace agreement at Beale Springs that the raids and the fighting subsided. However, the agreement lasted only nine months when it was broken with the murder of Chief Wauba Yuba near present-day Kingman during a dispute with the Walker party over the treaty.

After the chief's murder, raids by the Hualapai began in full force on mining camps and settlers. The cavalry from Fort Mojave responded, with the assistance of the Mohave, by attacking Hualapai rancherias and razing them. The pivotal engagement took place in January 1868, when Captain S.B.M. Young, later joined in by Lt. Johnathan D. Stevenson, surprised the rancheria of Sherum with his more than one hundred warriors. Known as the Battle of Cherum Peak, it lasted all day. Stevenson fell in the first volley. The Hualapai managed to escape, but lost twenty-one warriors, with many more wounded. The Battle broke the military resistance of the Hualapai. The Hualapai began to surrender, as whooping cough and dysentery weakened their ranks, on August 20, 1868.[5] They were led by Chief Leve Leve (Levi-Levi, half-brother to Sherum and Hualapai Charley)[6] of the Amat Whala Pa'a (Mad hwa:la Ba:' - “Hualapai Mountains band”) of the Yavapai Fighters subtribe. The warrior Sherum, who was known for his tenacity as a warrior, later surrendered, thus marking the end of the Hualapai Wars in 1870. It is estimated that one-third of the Hualapai people were killed during this war either by the conflict or disease.

Hualapai bands and villages

.jpg)

.jpg)

Ethnically, the Havasupai and the Hualapai are one people, although today, they are politically separate groups as the result of U.S. government policy. The Hualapai (Pa'a or Pai) had three subtribes - the Middle Mountain People in the northwest, Plateau People in the east, and Yavapai Fighter in the south (McGuire; 1983). The subtribes were divided into seven bands (Kroeber; 1935, Manners; 1974), which themselves were broken up into thirteen (original fourteen)[7][8] regional bands or local groups (Dobyns and Euler; 1970).[9] The local groups were composed of several extended family groups, living in small villages:[10] The Havasupai were one band of the Plateau People subtribe.[11]

Plateau People

Ko'audva Kopaya[12] included seven bands in the plateau and canyon country east of the Grand Wash Cliffs, the eastern Hualapai Valley, this area include the current Hualapai Reservation, bands listed from west to east:

- Mata'va-kapai (“Northern People”)

- Haduva Ba:' (“Clay Springs band”)

- Tafiika Ha'la Pa'a (Danyka Ba:', “Grass Springs band”)

Villages (along the edge of the Grand Wash Cliffs): Hadū'ba, Hai'ya, Hathekáva-kió, Huwuskót, Kahwāga, Kwa'thekithe'i'ta, Mati'bika, Tanyika'

- Ko'o'u-kapai (“Mesa People”)

- Qwaq We' Ba:' (“Hackberry band” or “Hackberry Springs band”)

- He:l Ba:' (“Milkweed Springs band”)

Villages (the largest settlements were near Milkweed Springs and Truxton Canyon): Crozier (American appellation), Djiwa'ldja, Hak-tala'kava, Haktutu'deva, Hê'l, Katha't-nye-ha', Muketega'de, Qwa'ga-we', Sewi', Taki'otha'wa, Wi-kanyo

- Nyav-kapai (“Eastern People”, occupied the Colorado Plateau and canyon lands)

- Yi Kwat Pa'a (Iquad Ba:' - “Peach Springs band”)

- Ha'kasa Pa'a (Hak saha Ba:' - “Pine Springs band”, also known as “Stinking Water band”, joint use areas in the northeastern part of Hualapai territory with the Havasooa Pa'a band)[13]

- Havasooa Pa'a (Hav'su Ba:', call themselves Havasu Baja or Havsuw’ Baaja - “People of the Blue Green Water”, also known as “Cataract Canyon band” of the Hualapai, today known as Havasupai)

Villages (not included are that of the Havasupai): Agwa'da, Ha'ke-takwi'va, Haksa', Hānya-djiluwa'ya, Tha've-nalnalwi'dje, Wiwakwa'ga, Yiga't

Middle Mountain People

Witoov Mi'uka Pa'a lived west of the Plateau People subtribe, ranged over the Cerbat and Black Mountains and portions of the Hualapai, Detrital, and Sacramento Valleys.

- Soto'lve-kapai (“Western People”)

- Wikawhata Pa'a (Wi gahwa da Ba:' - “Red Rock band”, lived in the northern portion of the area)

- Ha Emete Pa'a (Ha'emede: Ba:' - “Cerbat Mountain band”, also known as “White Rock Water band”, lived in the southern portion of the area, principally in the Cerbat Mountains)

Villages (most settlements were near springs along the eastern slopes of each mountain range): Chimethi'ap, Ha-kamuê', Háka-tovahádja, Hamte', Ha'theweli'-kio', Ivthi'ya-tanakwe, Kenyuā'tci, Kwatéhá, Nyi'l'ta, Quwl'-nye-há, Thawinūya, Waika'i'la, Wa-nye-ha', Wi'ka-tavata'va, Wi-kawea'ta, Winya'-ke-tawasa, Wiyakana'mo

Yavapai Fighters

Yavapai Fighters occupied the southern half of the Hualapai country and were the first to fight the enemy Yavapai - called by the Hualapai Ji'wha', “The Enemy” - living direct to their south, bands listed from west to east:

- Hual'la-pai (Howa'la-pai - “Pinery People”)

- Amat Whala Pa'a (Mad hwa:la Ba:' - “Hualapai Mountains band”, inhabited the Hualapai Mountains east of present-day Kingman westward to the Colorado River Valley)

Villages (were concentrated near springs and streams at the northern end of the range): Hake-djeka'dja, Ilwi'nya-ha', Kahwa't, Tak-tada'pa

- Kwe'va-kapai (Koowev Kopai) (“Southern People”)

- Tekiauvla Pa'a (Teki'aulva Pa'a - “Big Sandy River band”, also known as Haksigaela Ba:', occupied the reach of permanent river flow along the Big Sandy River between Wikieup and Signal, although ranged over in the adjacent mountain slopes)

- Burro Creek band (lived on the southern tip of the territory of the Tekiauvla Pa'a, farmed along streams and throughout canyons and plateaus along both sides of Burro Creek, intermarried oft with adjacent Yavapai - therefore they were oft mistaken by the Americans for Yavapai)[14]

Villages: Chivekaha', Djimwā'nsevio', Ha-djiluwa'ya, Hapu'k, Kwakwa', Kwal-hwa'ta, Kwathā'wa, Tak-mi'nva

- Hakia'tce-pai (“Mohon Mountain People”, also known as Talta'l-kuwa, occupied rugged mountain country)

- Ha Kiacha Pa'a (Ha gi a:ja Ba:' - “Mohon Mountains band”, also known as “Mahone Mountain band”, lived in the Mohon Mountains)

- Hwalgijapa Ba:' (“Juniper Mountains band”, lived in the Juniper Mountains)

Villages: Hakeskia'l, Hakia'ch, Ka'nyu'tekwa', Tha'va-ka-lavala'va, Wi-ka-tāva, Witevikivol, Witkitana'kwa

See also

- Bat Cave mine

- Grand Canyon Skywalk

- Kiowa Gordon, actor in New Moon

- Lucille Watahomigie, Hualapai linguist

Notes

- 1 2 The Hualapai Tribe Website. Accessed 2016-11-03

- ↑ Executive order

- ↑ Shepherd, JP (2008). ""At the Crossroads of Hualapai History, Memory, and American Colonization: Contesting Space and Place."". American Indian Quaterly. 32 (1): 16–42. Retrieved July 22, 2017. (Subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Walapai - Sociopolitical Organization

- ↑ National Register of Historic Places

- ↑ often Leve Leve is mistaken for a Yavapai leader - but he is actually only a band leader of the Yavapai Fighters subtribe, which were named for their fighting against the enemy Yavapai

- ↑ of the original 14 Hualapai bands or local groups the Red Rock band had completely mixed with the other bands before European American contact and were therefore not recognized as a distinct band

- ↑ Nina Swidler, Roger Anyon: Native Americans and Archaeologists: Stepping Stones to Common Ground, page 142, Alta Mira Press; 8. April 1997, ISBN 978-0761989011

- ↑ People of the Desert, Canyons and Pines: Prehistory of the Patayan Country in West Central Arizona, P. 27 The Hualapai Archived 2013-09-27 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ John R. Swanton: The Indian Tribes of North America, ISBN 978-0-8063-1730-4, 2003

- ↑ THE UPLAND YUMANS

- ↑ Thomas E. Sheridan: Arizona: A History, page 74, University of Arizona Press, 1995, ISBN 978-0816515158)

- ↑ About the Hualapai Nation

- ↑ Jeffrey P. Shepherd: We Are an Indian Nation: A History of the Hualapai People, University of Arizona Press, April 2010, ISBN 978-0816528288, page 142

References

- Intertribal Council of Arizona (Hualapai)

- Hualapai Reservation and Off-Reservation Trust Land, Arizona United States Census Bureau

- Hualapai Tribe

- The Havasupai and the Hualapai

- Camp Beale's Springs – Mohave Museum

- Thrapp, Dan L. (1967). The Conquest of Apacheria. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. LCCC 67-15588.

Further reading

- Billingsley, G.H. et al. (1999). Breccia-pipe and geologic map of the southwestern part of the Hualapai Indian Reservation and vicinity, Arizona [Miscellaneous Investigations Series; Map I-2554]. Reston, VA: U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Geological Survey.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hualapai. |