A. E. Housman

| A. E. Housman | |

|---|---|

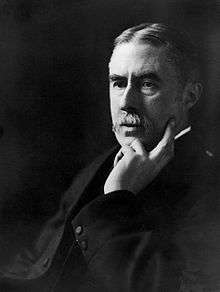

A. E. Housman photographed by E. O. Hoppé | |

| Born |

Alfred Edward Housman 26 March 1859 Bromsgrove, Worcestershire, England |

| Died |

30 April 1936 (aged 77) Cambridge, England |

| Pen name | A. E. Housman |

| Occupation | Classicist and poet |

| Nationality | British |

| Alma mater | St John's College, Oxford |

| Genre | Lyric poetry |

Alfred Edward Housman (/ˈhaʊsmən/; 26 March 1859 – 30 April 1936), usually known as A. E. Housman, was an English classical scholar and poet, best known to the general public for his cycle of poems A Shropshire Lad. Lyrical and almost epigrammatic in form, the poems wistfully evoke the dooms and disappointments of youth in the English countryside.[1] Their beauty, simplicity and distinctive imagery appealed strongly to late Victorian and Edwardian taste, and to many early 20th-century English composers both before and after the First World War. Through their song-settings, the poems became closely associated with that era, and with Shropshire itself.

Housman was one of the foremost classicists of his age and has been ranked as one of the greatest scholars who ever lived.[2][3] He established his reputation publishing as a private scholar and, on the strength and quality of his work, was appointed Professor of Latin at University College London and then at Cambridge. His editions of Juvenal, Manilius and Lucan are still considered authoritative.

Life

The eldest of seven children, Housman was born at Valley House in Fockbury, a hamlet on the outskirts of Bromsgrove in Worcestershire, to Sarah Jane (née Williams, married 17 June 1858 in Woodchester, Gloucester)[4] and Edward Housman (whose family came from Lancaster), and was baptised on 24 April 1859 at Christ Church, in Catshill.[5][6][7] His mother died on his twelfth birthday, and his father, a country solicitor, remarried, to an elder cousin, Lucy, in 1873. Housman's brother Laurence Housman and their sister Clemence Housman also became writers.

Housman was educated at King Edward's School in Birmingham and later Bromsgrove School, where he revealed his academic promise and won prizes for his poems.[7][8] In 1877 he won an open scholarship to St John's College, Oxford, where he studied classics.[7] Although introverted by nature, Housman formed strong friendships with two roommates, Moses Jackson and A. W. Pollard. Jackson became the great love of Housman's life, but he was heterosexual and did not reciprocate Housman's feelings.[9] Housman became an atheist while attending Oxford.[10][11] Housman obtained a first in classical Moderations in 1879, but his dedication to textual analysis, particularly of Propertius, led him to neglect the ancient history and philosophy that formed part of the Greats curriculum. Accordingly, he failed to obtain a degree.[7] Though some attribute Housman's unexpected failure in his final exams directly to his rejection by Jackson,[12] most biographers adduce more obvious causes. Housman was indifferent to philosophy and overconfident in his exceptional gifts; he felt contempt for inexact scholarship; and he enjoyed idling away his time with Jackson and others. He may also have been distracted by news of his father's desperate illness.[13][14][15] He felt deeply humiliated by his failure and became determined to vindicate his genius.

After Oxford, Jackson got a job as a clerk in the Patent Office in London and arranged a job there for Housman too.[7] The two shared a flat with Jackson's brother Adalbert until 1885, when Housman moved to lodgings of his own, probably after Jackson responded to a declaration of love by telling Housman that he could not reciprocate his feelings. Moses Jackson moved to India in 1887, placing more distance between himself and Housman. When Jackson returned briefly to England in 1889, to marry, Housman was not invited to the wedding and knew nothing about it until the couple had left the country. Adalbert Jackson died in 1892 and Housman commemorated him in a poem published as "XLII – A.J.J." of More Poems (1936).

Meanwhile, Housman pursued his classical studies independently, and published scholarly articles on such authors as Horace, Propertius, Ovid, Aeschylus, Euripides and Sophocles.[7] He gradually acquired such a high reputation that in 1892 he was offered and accepted the professorship of Latin at University College London (UCL).[7]

When R. W. Chambers discovered an immensely rare original Coverdale Bible of 1535 in the UCL library he presented it to the Library Committee, where Housman remarked that it would be better to sell it to "buy some really useful books with the proceeds".[16] From 1947, UCL's academic common room was dedicated to his memory as the Housman Room.[17]

In his private life Housman enjoyed gastronomy, flying in aeroplanes and making frequent visits to France, where he read "books which were banned in Britain as pornographic".[18] A. C. Benson, a fellow don, described him as being "descended from a long line of maiden aunts".[19]

Although Housman's early work and his responsibilities as a professor included both Latin and Greek, he began to specialise in Latin poetry. When asked later why he had stopped writing about Greek verse, he responded, "I found that I could not attain to excellence in both."[20]

In 1911 he took the Kennedy Professorship of Latin at Trinity College, Cambridge, where he remained for the rest of his life. G. P. Goold, Classics Professor at University College, wrote of Housman's accomplishments: "The legacy of Housman's scholarship is a thing of permanent value; and that value consists less in obvious results, the establishment of general propositions about Latin and the removal of scribal mistakes, than in the shining example he provides of a wonderful mind at work. … He was and may remain the last great textual critic." [3] Between 1903 and 1930 Housman published his critical edition of Manilius's Astronomicon in five volumes. He also edited works by Juvenal (1905) and Lucan (1926). Many colleagues were unnerved by his scathing attacks on those he thought guilty of shoddy scholarship.[7] In his paper "The Application of Thought to Textual Criticism" (1921) Housman wrote: "A textual critic engaged upon his business is not at all like Newton investigating the motion of the planets: he is much more like a dog hunting for fleas." He declared many of his contemporary scholars to be stupid, lazy, vain, or all three, saying: "Knowledge is good, method is good, but one thing beyond all others is necessary; and that is to have a head, not a pumpkin, on your shoulders, and brains, not pudding, in your head." [3][21]

His younger colleague A. S. F. Gow quoted examples of these attacks, noting that they "were often savage in the extreme".[22] Gow also related how Housman intimidated his students, sometimes reducing them to tears. According to Gow, Housman could never remember his students' names, maintaining that "had he burdened his memory by the distinction between Miss Jones and Miss Robinson, he might have forgotten that between the second and fourth declension". One notable pupil was Enoch Powell.[23] Housman found his true vocation in classical studies and treated his poems as secondary. He did not speak about his poetry in public until 1933 when he gave a lecture, "The Name and Nature of Poetry", in which he argued that poetry should appeal to emotions rather than to the intellect.

Housman died, aged 77, in Cambridge. His ashes are buried just outside St Laurence's Church, Ludlow, Shropshire.[7][24]

Poetry

A Shropshire Lad

Loveliest of trees, the cherry now

Loveliest of trees, the cherry now

Is hung with bloom along the bough,

And stands about the woodland ride

Wearing white for Eastertide.

Now, of my threescore years and ten,

Twenty will not come again,

And take from seventy springs a score,

It only leaves me fifty more.

And since to look at things in bloom

Fifty springs are little room,

About the woodlands I will go

To see the cherry hung with snow.

A Shropshire Lad II

During his years in London, A. E. Housman completed A Shropshire Lad, a cycle of 63 poems. After one publisher had turned it down, he helped subsidise its publication in 1896. At first selling slowly, it rapidly became a lasting success. Its appeal to English musicians had helped to make it widely known before World War I, when its themes struck a powerful chord with English readers. The book has been in print continuously since May 1896.[25]

The poems are marked by pessimism and preoccupation with death, without religious consolation. Housman wrote many of them while living in Highgate, London, before ever visiting Shropshire, which he presented in an idealised pastoral light as his 'land of lost content'.[26] Housman himself acknowledged that "No doubt I have been unconsciously influenced by the Greeks and Latins, but [the] chief sources of which I am conscious are Shakespeare’s songs, the Scottish Border ballads, and Heine.”[27]

Later collections

Housman began writing a new set of poems after the First World War. He was an influence on many British poets who became famous by their writing about the war, and wrote several poems as occasional verse to commemorate the war dead. This included his Epitaph on an Army of Mercenaries, honouring the British Expeditionary Force, an elite but small force of professional soldiers, 'a rapier amongst scythes'[28] sent to Belgium at the start of the war. Fighting a well-equipped and much larger German army, they suffered heavy losses.

In the early 1920s, when Moses Jackson was dying in Canada, Housman wanted to assemble his best unpublished poems so that Jackson could read them before his death.[7] These later poems, mostly written before 1910, show a greater variety of subject and form than those in A Shropshire Lad but lack the consistency of his previously published work. He published them as Last Poems (1922), feeling that his inspiration was exhausted and that he should not publish more in his lifetime. After his death Housman's brother, Laurence, published further poems in More Poems (1936), A. E .H.: Some Poems, Some Letters and a Personal Memoir by his Brother (1937), and Collected Poems (1939). A. E. H. includes humorous verse such as a parody of Longfellow's poem Excelsior. Housman also wrote a parodic Fragment of a Greek Tragedy, in English, published posthumously with humorous poems under the title Unkind to Unicorns.[29]

John Sparrow quoted a letter written late in Housman's life that described the genesis of his poems:

Poetry was for him …'a morbid secretion', as the pearl is for the oyster. The desire, or the need, did not come upon him often, and it came usually when he was feeling ill or depressed; then whole lines and stanzas would present themselves to him without any effort, or any consciousness of composition on his part. Sometimes they wanted a little alteration, sometimes none; sometimes the lines needed in order to make a complete poem would come later, spontaneously or with 'a little coaxing'; sometimes he had to sit down and finish the poem with his head. That... was a long and laborious process.[30]

Sparrow himself adds, "How difficult it is to achieve a satisfactory analysis may be judged by considering the last poem in A Shropshire Lad. Of its four stanzas, Housman tells us that two were 'given' him ready made; one was coaxed forth from his subconsciousness an hour or two later; the remaining one took months of conscious composition. No one can tell for certain which was which."[30]

De Amicitia (Of Friendship)

In 1942 Laurence Housman also deposited an essay entitled "A. E. Housman's 'De Amicitia'" in the British Library, with the proviso that it was not to be published for 25 years. The essay discussed A. E. Housman's homosexuality and his love for Moses Jackson.[31] Despite the conservative nature of the times and his own caution in public life, Housman was quite open in his poetry, and especially in A Shropshire Lad, about his deeper sympathies. Poem XXX of that sequence, for instance, speaks of how "Fear contended with desire": "Others, I am not the first, / Have willed more mischief than they durst". In More Poems, he buries his love for Moses Jackson in the very act of commemorating it, as his feelings of love are not reciprocated and must be carried unfulfilled to the grave:[32]

Because I liked you better

Than suits a man to say

It irked you, and I promised

To throw the thought away.

To put the world between us

We parted, stiff and dry;

Goodbye, said you, forget me.

I will, no fear, said I

If here, where clover whitens

The dead man's knoll, you pass,

And no tall flower to meet you

Starts in the trefoiled grass,

Halt by the headstone naming

The heart no longer stirred,

And say the lad that loved you

Was one that kept his word.[1]

- ^ A. E. Housman, More Poems, Jonathan Cape, London 1936 p.48

His poem "Oh who is that young sinner with the handcuffs on his wrists?", written after the trial of Oscar Wilde, addressed more general attitudes towards homosexuals.[33] In the poem the prisoner is suffering "for the colour of his hair", a natural quality that, in a coded reference to homosexuality, is reviled as "nameless and abominable" (recalling the legal phrase peccatum illud horribile, inter Christianos non nominandum, "that horrible sin, not to be named amongst Christians").

Housman song settings

Housman's poetry, especially A Shropshire Lad, was set to music by many British, and in particular English, composers in the first half of the 20th century.[3] The national, pastoral and traditional elements of his style resonated with similar trends in English music. In 1904 the cycle A Shropshire Lad was set by Arthur Somervell, who had begun to develop the concept of the English song-cycle in his version of Tennyson's Maud a little previously. Ralph Vaughan Williams produced his most famous settings of six songs, the cycle On Wenlock Edge, for string quartet, tenor and piano (dedicated to Gervase Elwes) in 1909,[34] and it became very popular after Elwes recorded it with the London String Quartet and Frederick B. Kiddle in 1917. Between 1909 and 1911 George Butterworth produced settings in two collections or cycles, as Six Songs from A Shropshire Lad, and Bredon Hill and Other Songs. He also wrote an orchestral tone poem on A Shropshire Lad, first performed at Leeds Festival under Arthur Nikisch in 1912.[35]

Ivor Gurney, another most important setter of Housman, composed a work for voice and string quartet (Ludlow and Teme), and a song-cycle on Housman works, both of which won the Carnegie Award.[36] The fatalism of the poems and their earlier settings foreshadowed responses to the universal bereavement of the First World War and became assimilated into them. This was reinforced when their foremost interpreter and performer, Gervase Elwes, died in an accident in 1921.

Among other composers who set Housman songs were John Ireland (song cycle, The Land of Lost Content (1920–21)), Michael Head (e.g. 'Ludlow Fair'), Graham Peel (a famous version of 'In Summertime on Bredon'), Ian Venables (Songs of Eternity and Sorrow), and the American Samuel Barber (e.g. 'With rue my heart is laden'). Gerald Finzi began several settings, but never finished them. Even composers not directly associated with the 'pastoral' tradition, such as Arnold Bax, Lennox Berkeley and Arthur Bliss, were attracted to Housman's poetry. A 1976 catalogue listed 400 musical settings of Housman's poems.[37] As of 2016, Lieder Net Archive records 606 settings of 187 texts.[38]

Commemorations

The earliest commemoration of Housman was in his college chapel in Cambridge, where there is a memorial brass on the south wall.[39] The Latin inscription was composed by his colleague there, A.S.F. Gow, who was also the author of a biographical and bibliographical sketch published immediately following his death.[40] Translated into English, the memorial reads:

This inscription commemorates Alfred Edward Housman, who was for twenty-five years Kennedy Professor of Latin and Fellow of the College. Following in Bentley’s footsteps he corrected the transmitted text of the Latin poets with so keen an intelligence and so ample a stock of learning, and chastised the sloth of editors so sharply and wittily, that he takes his place as the virtual second founder of textual studies. He was also a poet whose slim volumes of verse assured him of a secure place on the British Helicon. He died on 30th April 1936 at the age of seventy-six.[41]

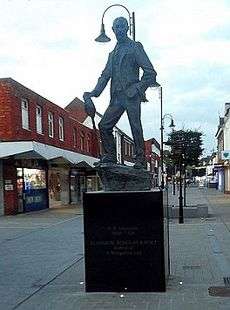

Blue plaques followed later, the first being on Byron Cottage in Highgate in 1969, recording the fact that A Shropshire Lad was written there. More followed on his Worcestershire birthplace, his homes and school in Bromsgrove.[42] The latter were encouraged by the Housman Society, which was founded in the town in 1973.[43] Another initiative was the statue in Bromsgrove High Street, showing the poet striding with walking stick in hand. The work of local sculptor Kenneth Potts, it was unveiled on 22 March 1985.[44]

The blue plaques in Worcestershire were set up on the centenary of A Shropshire Lad in 1996. In September of the same year a memorial window lozenge was dedicated at Poets' Corner in Westminster Abbey[45] The following year saw the première of Tom Stoppard's play The Invention of Love, whose subject is the relationship between Housman and Moses Jackson.[46]

As the 150th anniversary of his birth approached, London University inaugurated its Housman lectures on classical subjects in 2005, initially given every second year then annually after 2011.[47] The anniversary itself in 2009 saw the launch of a new edition of A Shropshire Lad, including pictures from across Shropshire taken by local photographer Gareth Thomas.[48] Among other events, there were performances of Vaughan Williams' On Wenlock Edge and Gurney's Ludlow and Teme at St Laurence's Church in Ludlow.[49]

Works

Poetry collections

- A Shropshire Lad (1896)

- Last Poems (1922, Henry Holt & Company)

- A Shropshire Lad: Authorized Edition (1924, Henry Holt & Company)

- More Poems (1936, Barclays)

- Collected Poems (1940, Henry Holt & Company)

- Collected Poems (1939); the poems included in this volume but not the three above are known as Additional Poems. The Penguin Edition of 1956 includes an Introduction by John Sparrow.

- Manuscript Poems: Eight Hundred Lines of Hitherto Un-collected Verse from the Author's Notebooks, ed. Tom Burns Haber (1955)

- Is My Team Ploughing

- Unkind to Unicorns: Selected Comic Verse, ed. J. Roy Birch (1995; 2nd ed. 1999)

- The Poems of A.E. Housman, ed. Archie Burnett (1997)

Classical scholarship

- P. Ovidi Nasonis Ibis (1894. In J.P. Postgate's "Corpus Poetarum Latinorum")

- M. Manilii Astronomica (1903–1930; 2nd ed. 1937; 5 vols.)

- D. Iunii Iuuenalis Saturae: editorum in usum edidit (1905; 2nd ed. 1931)

- M. Annaei Lucani, Belli Ciuilis, Libri Decem: editorum in usum edidit (1926; 2nd ed. 1927)

- The Classical Papers of A. E. Housman, ed. J. Diggle and F. R. D. Goodyear (1972; 3 vols.)

- William White, "Housman's Latin Inscriptions", CJ (1955) 159 – 166

Published lectures

These lectures are listed by date of delivery, with date of first publication given separately if different.

- Introductory Lecture (1892)

- "Swinburne" (1910; published 1969)

- Cambridge Inaugural Lecture (1911; published 1969 as "The Confines of Criticism")

- "The Application of Thought to Textual Criticism" (1921; published 1922)

- "The Name and Nature of Poetry" (1933)

Prose collections

Selected Prose, edited by John Carter, Cambridge University Press, 1961

Collected letters

- The Letters of A. E. Housman, ed. Henry Maas (1971)

- The Letters of A. E. Housman, ed. Archie Burnett (2007)

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ A E Housman, The Poetry Archive

- ↑ 'a man who turned out to be not only the great English classical scholar of his time but also one of the few real and great scholars anywhere at any time'. Charles Oscar Brink, English Classical Scholarship: Historical reflections on Bentley, Porson and Housman, James Clarke & Co, Oxford, Oxford University Press, New York, 1986 p.149

- 1 2 3 4 Poetry Foundation profile

- ↑ "England Marriages, 1538–1973 for Edward Housman", Baptism record via Family Search.org

- ↑ "England Births and Christenings, 1538–1975 for Alfred Edward Housman", Baptism record via Family Search.org

- ↑ Christ Church Catshill

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Profile at Poets.org

- ↑ "Housman's 150th birthday". BBC. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- ↑ Summers (1995) p. 371

- ↑ Blocksidge, Martin. A.E. Housman: A Single Life. N.p.: n.p., 2016. Print. "Housman became an atheist whilst at Oxford..."

- ↑ Page, Norman. A.E. Housman, a Critical Biography. New York: Schocken, 1983. Print. "He became a deist at thirteen and an atheist at twenty-one."

- ↑ Cunningham (2000) p. 981.

- ↑ Norman Page, Macmillan, London (1983) A. E. Housman: A Critical Biography pp. 43–46

- ↑ Richard Perceval Graves, A. E. Housman: The Scholar-Poet Charles Scribners, New York (1979) pp. 52–55.

- ↑ Charles Oscar Brink, English Classical Scholarship pp.152

- ↑ Ricks, Christopher (1989). A. E. Housman. Collected Poems and Selected Prose. Harmondsworth: Penguin. p. 18.

- ↑ "History of the ASCR". UCL.

- ↑ Graves (1979) p155.

- ↑ Critchley (1988).

- ↑ Gow (Cambridge 1936) p5

- ↑ "The Application of Thought to Textual Criticism," (1921) Housman

- ↑ Gow (Cambridge 1936) p. 24

- ↑ Gow (Cambridge 1936) p. 18

- ↑ Wilson, Scott. Resting Places: The Burial Sites of More Than 14,000 Famous Persons, 3d ed.: 2 (Kindle Location 22231). McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers. Kindle Edition

- ↑ Peter Parker, Housman Country, London 2016, Chapter 1

- ↑ A. E. Housman, A Shropshire Lad, XL

- ↑ Richard Stokes, The Penguin Book of English Song, 2016, p.li

- ↑ Liddell Harte, B. H. (1930). The Real War, 1914–1918, p.42. Republished by Wildside Press, LLC, 2012. ISBN 978-1479412150

- ↑ J. Roy Birch and Norman Page, ed. (1995). Unkind to Unicorns. Cambridge: Silent Books.

- 1 2 Collected Poems Penguin, Harmondsworth (1956), preface by John Sparrow.

- ↑ Summers ed. 1995, 371.

- ↑ Summers (1995) p372.

- ↑ Housman (1937) p213.

- ↑ W. and R. Elwes, Gervase Elwes, The Story of his Life (Grayson and Grayson, London 1935), p. 195-97.

- ↑ Arthur Eaglefield Hull, A Dictionary of Modern Music and Musicians Dent, London (1924), 73.

- ↑ Eaglefield-Hull (1924) p205.

- ↑ Palmer and Banfield 2001.

- ↑ LNA, list of authors

- ↑ Trinity College chapel

- ↑ A.E.Housman, Classical Scholar, Bloomsbury 2009, N. Hopkinson, “Housman and J.P. Postgate”

- ↑ In its original Latin the plaque reads: HOC TITVLO COMMEMORATVR / ALFRED EDWARD HOUSMAN [sic] / PER XXV ANNOS LINGVAE LATINAE PROFESSOR KENNEDIANVS / ET HVIVS COLLEGII SOCIVS / QVI BENTLEII INSISTENS VESTIGIIS / TEXTVM TRADITVM POETARVM LATINORVM / TANTO INGENII ACVMINE TANTIS DOCTRINAE COPIIS / EDITORVM SOCORDIAM / TAM ACRI CAVILLATIONE CASTIGAVIT / VT HORVM STVDIORVM PAENE REFORMATOR EXSTITERIT / IDEM POETA / TENVI CARMINVM FASCICVLO / SEDEM SIBI TVTAM IN HELICONE NOSTRO VINDICAVIT / OBIIT PRID.KAL.MAI./ A.S.MDCCCCXXXVI AETATIS SVAE LXXVII

- ↑ Open Plaques

- ↑ Housman Society Newsletter 38, “Early history of the Society”, pp.7–8

- ↑ Public Monuments and Sculpture Association

- ↑ Westminster Abbey.

- ↑ Guardian article"Hades and gentlemen" 5 October 1997

- ↑ UCL

- ↑ Merlin Unwin

- ↑ "A.E. Housman: 150th birth anniversary", Shropshire Life, 21 April 2007

Sources

- Critchley, Julian, 'Homage to a lonely lad', Weekend Telegraph (UK), 23 April 1988.

- Cunningham, Valentine ed., The Victorians: An Anthology of Poetry and Poetics (Oxford: Blackwell, 2000)

- Gow, A. S. F., A. E. Housman: A Sketch Together with a List of his Writings and Indexes to his Classical Papers (Cambridge 1936)

- Graves, Richard Perceval, A.E. Housman: The Scholar-Poet (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1979), p. 155

- Housman, Laurence, A. E .H.: Some Poems, Some Letters and a Personal Memoir by his Brother (London: Jonathan Cape, 1937)

- Page, Norman, ‘Housman, Alfred Edward (1859–1936)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004)

- Palmer, Christopher and Stephen Banfield, 'A. E. Housman', The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (London: Macmillan, 2001)

- Richardson, Donna, 'The Can Of Ail: A. E. Housman’s Moral Irony,' Victorian Poetry, Volume 48, Number 2, Summer 2010 (267–285)

- Shaw, Robin, "Housman's Places" (The Housman Society, 1995)

- Summers, Claude J. ed., The Gay and Lesbian Literary Heritage (New York: Henry Holt and Co., 1995)

Further reading

- Brink, C. O. Lutterworth.com, English Classical Scholarship: Historical Reflections on Bentley, Porson and Housman, James Clarke & Co (2009), ISBN 978-0-227-17299-5.

- C. Efrati, The road of danger, guilt, and shame: the lonely way of A. E. Housman (Associated University Presse, 2002) ISBN 0-8386-3906-2

- Philip Gardner ed., A. E. Housman: The Critical Heritage, a collection of reviews and essays on Housman’s poetry (London: Routledge 1992)

- Holden, A. W. and J. R. Birch, A. E Housman – A Reassessment (Palgrave Macmillan, London 1999)

- Peter Parker: Housman country : into the heart of England, London : Little, Brown, [2016], ISBN 978-1-4087-0613-8

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: A. E. Housman |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Alfred Edward Housman |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Alfred Edward Housman. |

- Bibliowiki has original media or text related to this article: Alfred Edward Housman (in the public domain in Canada)

- Profile and poems at Poets.org

- Profile and poems at Poetry Foundation

- London Review of Books review of "The Letters of A.E. Housman" 5 July 2007

- BBC Profile 24 June 2009

- "Star man": An article in the TLS by Robert Douglas Fairhurst, 20 June 2007

- "Lost Horizon: The sad and savage wit of A. E. Housman" New Yorker article (5 pages) by Anthony Lane 19 February 2001

- The Housman Society

- The Papers of A. E. Housman, Bryn Mawr College Special Collections

- Recording of part of the 1996 Shropshire Lad centenary reading by the Housman Society

- Catalogus Philologorum Classicorum

Works

- Works by A. E. Housman at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about A. E. Housman at Internet Archive

- Works by A. E. Housman at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Works by A. E. Housman at Open Library