House sparrow

| House sparrow | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| Male in Germany | |

| |

| Female in England | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Passeridae |

| Genus: | Passer |

| Species: | P. domesticus |

| Binomial name | |

| Passer domesticus (Linnaeus, 1758) | |

| |

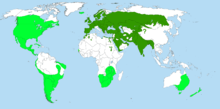

| Native range Introduced range | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

|

Fringilla domestica Linnaeus, 1758 | |

The house sparrow (Passer domesticus) is a bird of the sparrow family Passeridae, found in most parts of the world. A small bird, it has a typical length of 16 cm (6.3 in) and a mass of 24–39.5 g (0.85–1.39 oz). Females and young birds are coloured pale brown and grey, and males have brighter black, white, and brown markings. One of about 25 species in the genus Passer, the house sparrow is native to most of Europe, the Mediterranean region, and much of Asia. Its intentional or accidental introductions to many regions, including parts of Australia, Africa, and the Americas, make it the most widely distributed wild bird.

The house sparrow is strongly associated with human habitations, and can live in urban or rural settings. Though found in widely varied habitats and climates, it typically avoids extensive woodlands, grasslands, and deserts away from human development. It feeds mostly on the seeds of grains and weeds, but it is an opportunistic eater and commonly eats insects and many other foods. Its predators include domestic cats, hawks, owls, and many other predatory birds and mammals.

Because of its numbers, ubiquity, and association with human settlements, the house sparrow is culturally prominent. It is extensively, and usually unsuccessfully, persecuted as an agricultural pest. It has also often been kept as a pet, as well as being a food item and a symbol of lust, sexual potency, commonness, and vulgarity. Though it is widespread and abundant, its numbers have declined in some areas. The animal's conservation status is listed as least concern on the IUCN Red List.

Description

Measurements and shape

The house sparrow is typically about 16 cm (6.3 in) long, ranging from 14 to 18 cm (5.5 to 7.1 in).[3] It is a compact bird with a full chest and a large, rounded head. Its bill is stout and conical with a culmen length of 1.1–1.5 cm (0.43–0.59 in), strongly built as an adaptation for eating seeds. Its tail is short, at 5.2–6.5 cm (2.0–2.6 in) long. The wing chord is 6.7–8.9 cm (2.6–3.5 in), and the tarsus is 1.6–2.5 cm (0.63–0.98 in).[4][5] In mass, the house sparrow ranges from 24 to 39.5 g (0.85 to 1.39 oz). Females usually are slightly smaller than males. The median mass on the European continent for both sexes is about 30 g (1.1 oz), and in more southerly subspecies is around 26 g (0.92 oz). Younger birds are smaller, males are larger during the winter, and females are larger during the breeding season.[6] Birds at higher latitudes, colder climates, and sometimes higher altitudes are larger (under Bergmann's rule), both between and within subspecies.[6][7][8][9]

Plumage

The plumage of the house sparrow is mostly different shades of grey and brown. The sexes exhibit strong dimorphism: the female is mostly buffish above and below, while the male has boldly coloured head markings, a reddish back, and grey underparts.[8] The male has a dark grey crown from the top of its bill to its back, and chestnut brown flanking its crown on the sides of its head. It has black around its bill, on its throat, and on the spaces between its bill and eyes (lores). It has a small white stripe between the lores and crown and small white spots immediately behind the eyes (postoculars), with black patches below and above them. The underparts are pale grey or white, as are the cheeks, ear coverts, and stripes at the base of the head. The upper back and mantle are a warm brown, with broad black streaks, while the lower back, rump and uppertail coverts are greyish brown.[10]

-_Female_in_Kolkata_I_IMG_3787_(cropped).jpg)

The male is duller in fresh nonbreeding plumage, with whitish tips on many feathers. Wear and preening expose many of the bright brown and black markings, including most of the black throat and chest patch, called the "bib" or "badge".[10][11] The badge is variable in width and general size, and may signal social status or fitness. This hypothesis has led to a "veritable 'cottage industry'" of studies, which have only conclusively shown that patches increase in size with age.[12] The male's bill is black in the breeding season and horn (dark grey) during the rest of the year.[3]

.jpg)

The female has no black markings or grey crown. Its upperparts and head are brown with darker streaks around the mantle and a distinct pale supercilium. Its underparts are pale grey-brown. The female's bill is brownish-grey and becomes darker in breeding plumage approaching the black of the male's bill.[3][10]

Juveniles are similar to the adult female, but deeper brown below and paler above, with paler and less defined supercilia. Juveniles have broader buff feather edges, and tend to have looser, scruffier plumage, like moulting adults. Juvenile males tend to have darker throats and white postoculars like adult males, while juvenile female tend to have white throats. However, juveniles cannot be reliably sexed by plumage: some juvenile males lack any markings of the adult male, and some juvenile females have male features. The bills of young birds are light yellow to straw, paler than the female's bill. Immature males have paler versions of the adult male's markings, which can be very indistinct in fresh plumage. By their first breeding season, young birds generally are indistinguishable from other adults, though they may still be paler during their first year.[3][10]

Voice

Most house sparrow vocalisations are variations on its short and incessant chirping call. Transcribed as chirrup, tschilp, or philip, this note is made as a contact call by flocking or resting birds, or by males to proclaim nest ownership and invite pairing. In the breeding season, the male gives this call repetitively, with emphasis and speed, but not much rhythm, forming what is described either as a song or an "ecstatic call" similar to a song.[13][14] Young birds also give a true song, especially in captivity, a warbling similar to that of the European greenfinch.[15]

Aggressive males give a trilled version of their call, transcribed as "chur-chur-r-r-it-it-it-it". This call is also used by females in the breeding season, to establish dominance over males while displacing them to feed young or incubate eggs.[16] House sparrows give a nasal alarm call, the basic sound of which is transcribed as quer, and a shrill chree call in great distress.[17] Another vocalisation is the "appeasement call", a soft quee given to inhibit aggression, usually given between birds of a mated pair.[16] These vocalisations are not unique to the house sparrow, but are shared, with small variations, by all sparrows.[18]

Variation

-_Male_in_Kolkata_I_IMG_5904.jpg)

Some variation is seen in the 12 subspecies of house sparrows, which are divided into two groups, the Oriental P. d. indicus group, and the Palaearctic P. d. domesticus group. Birds of the P. d. domesticus group have grey cheeks, while P. d. indicus group birds have white cheeks, as well as bright colouration on the crown, a smaller bill, and a longer black bib.[19] The subspecies P. d. tingitanus differs little from the nominate subspecies, except in the worn breeding plumage of the male, in which the head is speckled with black and underparts are paler.[20] P. d. balearoibericus is slightly paler than the nominate, but darker than P. d. bibilicus.[21] P. d. bibilicus is paler than most subspecies, but has the grey cheeks of P. d. domesticus group birds. The similar P. d. persicus is paler and smaller, and P. d. niloticus is nearly identical but smaller.[20] Of the less widespread P. d. indicus group subspecies, P. d. hyrcanus is larger than P. d. indicus, P. d. hufufae is paler, P. d. bactrianus is larger and paler, and P. d. parkini is larger and darker with more black on the breast than any other subspecies.[20][22][23]

Identification

The house sparrow can be confused with a number of other seed-eating birds, especially its relatives in the genus Passer. Many of these relatives are smaller, with an appearance that is neater or "cuter", as with the Dead Sea sparrow.[24] The dull-coloured female can often not be distinguished from other females, and is nearly identical to those of the Spanish and Italian sparrows.[10] The Eurasian tree sparrow is smaller and more slender with a chestnut crown and a black patch on each cheek.[25] The male Spanish sparrow and Italian sparrow are distinguished by their chestnut crowns. The Sind sparrow is very similar but smaller, with less black on the male's throat and a distinct pale supercilium on the female.[10]

Taxonomy and systematics

Names

The house sparrow was among the first animals to be given a scientific name in the modern system of biological classification, since it was described by Carl Linnaeus, in the 1758 10th edition of Systema Naturae. It was described from a type specimen collected in Sweden, with the name Fringilla domestica.[26][27] Later, the genus name Fringilla came to be used only for the common chaffinch and its relatives, and the house sparrow has usually been placed in the genus Passer created by French zoologist Mathurin Jacques Brisson in 1760.[28][29]

The bird's scientific name and its usual English name have the same meaning. The Latin word passer, like the English word "sparrow", is a term for small active birds, coming from a root word referring to speed.[30][31] The Latin word domesticus means "belonging to the house", like the common name a reference to its association with humans.[32] The house sparrow is also called by a number of alternative English names, including English sparrow, chiefly in North America;[33][34] and Indian sparrow or Indian house sparrow, for the birds of the Indian subcontinent and Central Asia.[35] Dialectal names include sparr, sparrer, spadger, spadgick, and philip, mainly in southern England; spug and spuggy, mainly in northern England; spur and sprig, mainly in Scotland;[36][37] and spatzie or spotsie, from the German Spatz, in North America.[38]

Taxonomy

The genus Passer contains about 25 species, depending on the authority, 26 according to the Handbook of the Birds of the World.[39] Most Passer species are dull-coloured birds with short, square tails and stubby, conical beaks, between 11 and 18 cm (4.3 and 7.1 in) long.[8][40] Mitochondrial DNA studies suggest that speciation in the genus occurred during the Pleistocene and earlier, while other evidence suggests speciation occurred 25,000 to 15,000 years ago.[41][42] Within Passer, the house sparrow is part of the "Palaearctic black-bibbed sparrows" group and a close relative of the Mediterranean "willow sparrows".[39][43]

The taxonomy of the house sparrow and its Mediterranean relatives is highly complicated. The common type of "willow sparrow" is the Spanish sparrow, which resembles the house sparrow in many respects.[44] It frequently prefers wetter habitats than the house sparrow, and it is often colonial and nomadic.[45] In most of the Mediterranean, one or both species occur, with some degree of hybridisation.[46] In North Africa, the two species hybridise extensively, forming highly variable mixed populations with a full range of characters from pure house sparrows to pure Spanish sparrows.[47][48][49]

In much of Italy, a form apparently intermediate between the house and Spanish sparrows, is known as the Italian sparrow. It resembles a hybrid between the two species, and is in other respects intermediate. Its specific status and origin are the subject of much debate.[48][50] In the Alps, the Italian sparrow intergrades over a roughly 20 km (12 mi) strip with the house sparrow,[51] but to the south it intergrades over the southern half of Italy and some Mediterranean islands with the Spanish sparrow.[48] On the Mediterranean islands of Malta, Gozo, Crete, Rhodes, and Karpathos, the other apparently intermediate birds are of unknown status.[48][52][53]

Subspecies

A large number of subspecies have been named, of which 12 were recognised in the Handbook of the Birds of the World. These subspecies are divided into two groups, the Palaearctic P. d. domesticus group, and the Oriental P. d. indicus group.[39] Several Middle Eastern subspecies, including P. d. biblicus, are sometimes considered a third, intermediate group. The subspecies P. d. indicus was described as a species, and was considered to be distinct by many ornithologists during the 19th century.[19]

Migratory birds of the subspecies P. d. bactrianus in the P. d. indicus group were recorded overlapping with P. d. domesticus birds without hybridising in the 1970s, so the Soviet scientists Edward I. Gavrilov and M. N. Korelov proposed the separation of the P. d. indicus group as a separate species.[28][54] However, P. d. indicus-group and P. d. domesticus-group birds intergrade in a large part of Iran, so this split is rarely recognised.[39]

In North America, house sparrow populations are more differentiated than those in Europe.[7] This variation follows predictable patterns, with birds at higher latitudes being larger and those in arid areas being paler.[8][55][56] However, how much this is caused by evolution or by environment is not clear.[57][58][59][60] Similar observations have been made in New Zealand,[61] and in South Africa.[62] The introduced house sparrow populations may be distinct enough to merit subspecies status, especially in North America and southern Africa,[39] and American ornithologist Harry Church Oberholser even gave the subspecies name P. d. plecticus to the paler birds of western North America.[55]

- P. d. domesticus group

- P. d. domesticus, the nominate subspecies, is found in most of Europe, across northern Asia to Sakhalin and Kamchatka. It is the most widely introduced subspecies.[26]

- P. d. balearoibericus von Jordans, 1923, described from Majorca, is found in the Balearic Islands, southern France, the Balkans, and Anatolia.[39]

- P. d. tingitanus (Loche, 1867), described from Algeria, is found in the Maghreb from Ajdabiya in Libya to Béni Abbès in Algeria, and to Morocco's Atlantic coast. It hybridises extensively with the Spanish sparrow, especially in the eastern part of its range.[63]

- P. d. niloticus Nicoll and Bonhote, 1909, described from Faiyum, Egypt, is found along the Nile north of Wadi Halfa, Sudan. It intergrades with bibilicus in the Sinai, and with rufidorsalis in a narrow zone around Wadi Halfa. It has been recorded in Somaliland.[63][64]

- P. d. persicus Zarudny and Kudashev, 1916, described from the Karun River in Khuzestan, Iran, is found in the western and central Iran south of the Alborz mountains, intergrading with indicus in eastern Iran, and Afghanistan.[39][63][65]

- P. d. biblicus Hartert, 1910, described from Palestine, is found in the Middle East from Cyprus and south-eastern Turkey to the Sinai in the west and from Azerbaijan to Kuwait in the east.[39][63]

- P. d. indicus group

- P. d. hyrcanus Zarudny and Kudashev, 1916, described from Gorgan, Iran, is found along the southern coast of the Caspian Sea from Gorgan to south-eastern Azerbaijan. It intergrades with P. d. persicus in the Alborz mountains, and with P. d. bibilicus to the west. It is the subspecies with the smallest range.[39][63]

- P. d. bactrianus Zarudny and Kudashev, 1916, described from Tashkent, is found in southern Kazakhstan to the Tian Shan and northern Iran and Afghanistan. It intergrades with persicus in Baluchistan and with indicus across central Afghanistan. Unlike most other house sparrow subspecies, it is almost entirely migratory, wintering in the plains of the northern Indian subcontinent. It is found in open country rather than in settlements, which are occupied by the Eurasian tree sparrow in its range.[39][63] There is an exceptional record from Sudan.[64]

- P. d. parkini Whistler, 1920, described from Srinagar, Kashmir, is found in the western Himalayas from the Pamir Mountains to south-eastern Nepal. It is migratory, like P. d. bactrianus.[19][63]

- P. d. indicus Jardine and Selby, 1831, described from Bangalore, is found in the Indian subcontinent south of the Himalayas, in Sri Lanka, western Southeast Asia, eastern Iran, south-western Arabia and southern Israel.[19][39][63]

- P. d. hufufae Ticehurst and Cheeseman, 1924, described from Hofuf in Saudi Arabia, is found in north-eastern Arabia.[63][66]

- P. d. rufidorsalis C. L. Brehm, 1855, described from Khartoum, Sudan, is found in the Nile valley from Wadi Halfa south to Renk in northern South Sudan,[63][64] and in eastern Sudan, northern Ethiopia to the Red Sea coast in Eritrea.[39] It has also been introduced to Mohéli in the Comoros.[67]

Distribution and habitat

The house sparrow originated in the Middle East and spread, along with agriculture, to most of Eurasia and parts of North Africa.[68] Since the mid-19th century, it has reached most of the world, chiefly due to deliberate introductions, but also through natural and shipborne dispersal.[69] Its introduced range encompasses most of North America, Central America, southern South America, southern Africa, part of West Africa, Australia, New Zealand, and islands throughout the world.[70] It has greatly extended its range in northern Eurasia since the 1850s,[71] and continues to do so, as was shown by the colonisations around 1990 of Iceland and Rishiri Island, Japan.[72] The extent of its range makes it the most widely distributed wild bird on the planet.[70]

Introductions

The house sparrow has become highly successful in most parts of the world where it has been introduced. This is mostly due to its early adaptation to living with humans, and its adaptability to a wide range of conditions.[73][74] Other factors may include its robust immune response, compared to the Eurasian tree sparrow.[75] Where introduced, it can extend its range quickly, sometimes at a rate over 230 km (140 mi) per year.[76] In many parts of the world, it has been characterised as a pest, and poses a threat to native birds.[77][78] A few introductions have died out or been of limited success, such as those to Greenland and Cape Verde.[79]

The first of many successful introductions to North America occurred when birds from England were released in New York City, in 1852 [80][81] to control the ravages of the linden moth.[82] The house sparrow now occurs from the Northwest Territories to southern Panama,[4] and it is one of the most abundant birds in North America.[77] The house sparrow was first introduced to Australia in 1863 at Melbourne and is common throughout the eastern part of the continent,[79] but has been prevented from establishing itself in Western Australia, where every house sparrow found in the state is killed.[83] House sparrows were introduced in New Zealand in 1859, and from there reached many of the Pacific islands, including Hawaii.[84]

In southern Africa, birds of both the European subspecies P. d. domesticus and the Indian subspecies P. d. indicus were introduced around 1900. Birds of P. d. domesticus ancestry are confined to a few towns, while P. d. indicus birds have spread rapidly, reaching Tanzania in the 1980s. Despite this success, native relatives such as the Cape sparrow also occur in towns, competing successfully with it.[79][85] In South America, it was first introduced near Buenos Aires around 1870, and quickly became common in most of the southern part of the continent. It now occurs almost continuously from Tierra del Fuego to the fringes of the Amazon basin, with isolated populations as far north as coastal Venezuela.[79][86][87]

Habitat

The house sparrow is closely associated with human habitation and cultivation.[88] It is not an obligate commensal of humans as some have suggested: Central Asian house sparrows usually breed away from humans in open country,[89] and birds elsewhere are occasionally found away from humans.[88][90][91] The only terrestrial habitats that the house sparrow does not inhabit are dense forest and tundra. Well adapted to living around humans, it frequently lives and even breeds indoors, especially in factories, warehouses, and zoos.[88] It has been recorded breeding in an English coal mine 640 m (2,100 ft) below ground,[92] and feeding on the Empire State Building's observation deck at night.[93] It reaches its greatest densities in urban centres, but its reproductive success is greater in suburbs, where insects are more abundant.[88][94] On a larger scale, it is most abundant in wheat-growing areas such as the Midwestern United States.[95]

It tolerates a variety of climates, but prefers drier conditions, especially in moist tropical climates.[79][88] It has several adaptations to dry areas, including a high salt tolerance[96] and an ability to survive without water by ingesting berries.[97] In most of eastern Asia, the house sparrow is entirely absent, replaced by the Eurasian tree sparrow.[98] Where these two species overlap, the house sparrow is usually more common than the Eurasian tree sparrow, but one species may replace the other in a manner that ornithologist Maud Doria Haviland described as "random, or even capricious".[99] In most of its range, the house sparrow is extremely common, despite some declines,[100] but in marginal habitats such as rainforest or mountain ranges, its distribution can be spotty.[88]

Behaviour

Social behaviour

The house sparrow is a very social bird. It is gregarious at all seasons when feeding, often forming flocks with other types of birds.[101] It roosts communally, its nests are usually grouped together in clumps, and it engages in social activities such as dust or water bathing and "social singing", in which birds call together in bushes.[102][103] The house sparrow feeds mostly on the ground, but it flocks in trees and bushes.[102] At feeding stations and nests, female house sparrows are dominant despite their smaller size, and in the reproductive period (usually spring or summer), being dominant, they can fight for males.[104][105]

Sleep and roosting

House sparrows sleep with the bill tucked underneath the scapular feathers.[106] Outside of the reproductive season, they often roost communally in trees or shrubs. Much communal chirping occurs before and after the birds settle in the roost in the evening, as well as before the birds leave the roost in the morning.[102] Some congregating sites separate from the roost may be visited by the birds prior to settling in for the night.[107]

Body maintenance

Dust or water bathing is common and often occurs in groups. Anting is rare.[108] Head scratching is done with the leg over the drooped wing.[107]

Feeding

As an adult, the house sparrow mostly feeds on the seeds of grains and weeds, but it is opportunistic and adaptable, and eats whatever foods are available.[109] In towns and cities, it often scavenges for food in garbage containers and congregates in the outdoors of restaurants and other eating establishments to feed on leftover food and crumbs. It can perform complex tasks to obtain food, such as opening automatic doors to enter supermarkets,[110] clinging to hotel walls to watch vacationers on their balconies,[111] and nectar robbing kowhai flowers.[112] In common with many other birds, the house sparrow requires grit to digest the harder items in its diet. Grit can be either stone, often grains of masonry, or the shells of eggs or snails; oblong and rough grains are preferred.[113][114]

Several studies of the house sparrow in temperate agricultural areas have found the proportion of seeds in its diet to be about 90%.[109][115][116] It will eat almost any seeds, but where it has a choice, it prefers oats and wheat.[117] In urban areas, the house sparrow feeds largely on food provided directly or indirectly by humans, such as bread, though it prefers raw seeds.[116][118] The house sparrow also eats some plant matter besides seeds, including buds, berries, and fruits such as grapes and cherries.[97][116] In temperate areas, the house sparrow has an unusual habit of tearing flowers, especially yellow ones, in the spring.[119]

Animals form another important part of the house sparrow's diet, chiefly insects, of which beetles, caterpillars, dipteran flies, and aphids are especially important. Various noninsect arthropods are eaten, as are molluscs and crustaceans where available, earthworms, and even vertebrates such as lizards and frogs.[109] Young house sparrows are fed mostly on insects until about 15 days after hatching.[120] They are also given small quantities of seeds, spiders, and grit. In most places, grasshoppers and crickets are the most abundant foods of nestlings.[121] True bugs, ants, sawflies, and beetles are also important, but house sparrows take advantage of whatever foods are abundant to feed their young.[121][122][123] House sparrows have been observed stealing prey from other birds, including American robins.[4]

Locomotion

The house sparrow's flight is direct (not undulating) and flapping, averaging 45.5 km/h (28.3 mph) and about 15 wingbeats per second.[107][124] On the ground, the house sparrow typically hops rather than walks. It can swim when pressed to do so by pursuit from predators. Captive birds have been recorded diving and swimming short distances under water.[107]

Dispersal and migration

Most house sparrows do not move more than a few kilometres during their lifetimes. However, limited migration occurs in all regions. Some young birds disperse long distances, especially on coasts, and mountain birds move to lower elevations in winter.[102][125][126] Two subspecies, P. d. bactrianus and P. d. parkini, are predominantly migratory. Unlike the birds in sedentary populations that migrate, birds of migratory subspecies prepare for migration by putting on weight.[102]

Breeding

House sparrows can breed in the breeding season immediately following their hatching, and sometimes attempt to do so. Some birds breeding for the first time in tropical areas are only a few months old and still have juvenile plumage.[127] Birds breeding for the first time are rarely successful in raising young, and reproductive success increases with age, as older birds breed earlier in the breeding season, and fledge more young.[128] As the breeding season approaches, hormone releases trigger enormous increases in the size of the sexual organs and changes in day length lead males to start calling by nesting sites.[129][130] The timing of mating and egg-laying varies geographically, and between specific locations and years because a sufficient supply of insects is needed for egg formation and feeding nestlings.[131]

Males take up nesting sites before the breeding season, by frequently calling beside them. Unmated males start nest construction and call particularly frequently to attract females. When a female approaches a male during this period, the male displays by moving up and down while drooping and shivering his wings, pushing up his head, raising and spreading his tail, and showing his bib.[131] Males may try to mate with females while calling or displaying. In response, a female will adopt a threatening posture and attack a male before flying away, pursued by the male. The male displays in front of her, attracting other males, which also pursue and display to the female. This group display usually does not immediately result in copulations.[131] Other males usually do not copulate with the female.[132][133] Copulation is typically initiated by the female giving a soft dee-dee-dee call to the male. Birds of a pair copulate frequently until the female is laying eggs, and the male mounts the female repeatedly each time a pair mates.[131]

The house sparrow is monogamous, and typically mates for life. Birds from pairs often engage in extra-pair copulations, so about 15% of house sparrow fledglings are unrelated to their mother's mate.[134] Male house sparrows guard their mates carefully to avoid being cuckolded, and most extra-pair copulation occurs away from nest sites.[132][135] Males may sometimes have multiple mates, and bigamy is mostly limited by aggression between females.[136] Many birds do not find a nest and a mate, and instead may serve as helpers around the nest for mated pairs, a role which increases the chances of being chosen to replace a lost mate. Lost mates of both sexes can be replaced quickly during the breeding season.[132][137] The formation of a pair and the bond between the two birds is tied to the holding of a nest site, though paired house sparrows can recognise each other away from the nest.[131]

Nesting

Nest sites are varied, though cavities are preferred. Nests are most frequently built in the eaves and other crevices of houses. Holes in cliffs and banks, or tree hollows, are also used.[138][139] A sparrow sometimes excavates its own nests in sandy banks or rotten branches, but more frequently uses the nests of other birds such as those of swallows in banks and cliffs, and old tree cavity nests.[138] It usually uses deserted nests, though sometimes it usurps active ones.[138][140] Tree hollows are more commonly used in North America than in Europe,[138] putting the sparrows in competition with bluebirds and other North American cavity nesters, and thereby contributing to their population declines.[77]

Especially in warmer areas, the house sparrow may build its nests in the open, on the branches of trees, especially evergreens and hawthorns, or in the nests of large birds such as storks or magpies.[131][138][141] In open nesting sites, breeding success tends to be lower, since breeding begins late and the nest can easily be destroyed or damaged by storms.[138][142] Less common nesting sites include street lights and neon signs, favoured for their warmth; and the old open-topped nests of other songbirds, which are then domed over.[138][139]

The nest is usually domed, though it may lack a roof in enclosed sites.[138] It has an outer layer of stems and roots, a middle layer of dead grass and leaves, and a lining of feathers, as well as of paper and other soft materials.[139] Nests typically have external dimensions of 20 × 30 cm (8 × 12 in),[131] but their size varies greatly.[139] The building of the nest is initiated by the unmated male while displaying to females. The female assists in building, but is less active than the male.[138] Some nest building occurs throughout the year, especially after moult in autumn. In colder areas house sparrows build specially created roost nests, or roost in street lights, to avoid losing heat during the winter.[138][143] House sparrows do not hold territories, but they defend their nests aggressively against intruders of the same sex.[138]

House sparrows' nests support a wide range of scavenging insects, including nest flies such as Neottiophilum praestum, Protocalliphora blowflies,[144][145] and over 1,400 species of beetle.[146]

Eggs and young

Clutches usually comprise four or five eggs, though numbers from one to 10 have been recorded. At least two clutches are usually laid, and up to seven a year may be laid in the tropics or four a year in temperate latitudes. When fewer clutches are laid in a year, especially at higher latitudes, the number of eggs per clutch is greater. Central Asian house sparrows, which migrate and have only one clutch a year, average 6.5 eggs in a clutch. Clutch size is also affected by environmental and seasonal conditions, female age, and breeding density.[147][148]

Some intraspecific brood parasitism occurs, and instances of unusually large numbers of eggs in a nest may be the result of females laying eggs in the nests of their neighbours. Such foreign eggs are sometimes recognised and ejected by females.[147][149] The house sparrow is a victim of interspecific brood parasites, but only rarely, since it usually uses nests in holes too small for parasites to enter, and it feeds its young foods unsuitable for young parasites.[150][151] In turn, the house sparrow has once been recorded as a brood parasite of the American cliff swallow.[149][152]

The eggs are white, bluish white, or greenish white, spotted with brown or grey.[107] Subelliptical in shape,[8] they range from 20 to 22 mm (0.79 to 0.87 in) in length and 14 to 16 mm (0.55 to 0.63 in) in width,[4] have an average mass of 2.9 g (0.10 oz),[153] and an average surface area of 9.18 cm2 (1.423 in2).[154] Eggs from the tropical subspecies are distinctly smaller.[155][156] Eggs begin to develop with the deposition of yolk in the ovary a few days before ovulation. In the day between ovulation and laying, egg white forms, followed by eggshell.[157] Eggs laid later in a clutch are larger, as are those laid by larger females, and egg size is hereditary. Eggs decrease slightly in size from laying to hatching.[158] The yolk comprises 25% of the egg, the egg white 68%, and the shell 7%. Eggs are watery, being 79% liquid, and otherwise mostly protein.[159]

The female develops a brood patch of bare skin and plays the main part in incubating the eggs. The male helps, but can only cover the eggs rather than truly incubate them. The female spends the night incubating during this period, while the male roosts near the nest.[147] Eggs hatch at the same time, after a short incubation period lasting 11–14 days, and exceptionally for as many as 17 or as few as 9.[8][131][160] The length of the incubation period decreases as ambient temperature increases later in the breeding season.[161]

.jpg)

Young house sparrows remain in the nest for 11 to 23 days, normally 14 to 16 days.[107][161][162] During this time, they are fed by both parents. As newly hatched house sparrows do not have sufficient insulation, they are brooded for a few days, or longer in cold conditions.[161][163] The parents swallow the droppings produced by the hatchlings during the first few days; later, the droppings are moved up to 20 m (66 ft) away from the nest.[163][164]

The chicks' eyes open after about four days and, at an age of about eight days, the young birds get their first down.[107][162] If both parents perish, the ensuing intensive begging sounds of the young often attract replacement parents which feed them until they can sustain themselves.[163][165] All the young in the nest leave it during the same period of a few hours. At this stage, they are normally able to fly. They start feeding themselves partly after one or two days, and sustain themselves completely after 7 to 10 days, 14 at the latest.[166]

Survival

In adult house sparrows, annual survival is 45–65%.[167] After fledging and leaving the care of their parents, young sparrows have a high mortality rate, which lessens as they grow older and more experienced. Only about 20–25% of birds hatched survive to their first breeding season.[168] The oldest known wild house sparrow lived for nearly two decades; it was found dead 19 years and 9 months after it was ringed in Denmark.[169] The oldest recorded captive house sparrow lived for 23 years.[170] The typical ratio of males to females in a population is uncertain due to problems in collecting data, but a very slight preponderance of males at all ages is usual.[171]

Predation

The house sparrow's main predators are cats and birds of prey, but many other animals prey on them, including corvids, squirrels,[172] and even humans—the house sparrow has been consumed in the past by people in many parts of the world, and it still is in parts of the Mediterranean.[173] Most species of birds of prey have been recorded preying on the house sparrow in places where records are extensive. Accipiters and the merlin in particular are major predators, though cats are likely to have a greater impact on house sparrow populations.[172] The house sparrow is also a common victim of roadkill; on European roads, it is the bird most frequently found dead.[174]

Parasites and disease

The house sparrow is host to a huge number of parasites and diseases, and the effect of most is unknown. Ornithologist Ted R. Anderson listed thousands, noting that his list was incomplete.[175] The commonly recorded bacterial pathogens of the house sparrow are often those common in humans, and include Salmonella and Escherichia coli.[176] Salmonella is common in the house sparrow, and a comprehensive study of house sparrow disease found it in 13% of sparrows tested. Salmonella epidemics in the spring and winter can kill large numbers of sparrows.[175] The house sparrow hosts avian pox and avian malaria, which it has spread to the native forest birds of Hawaii.[177] Many of the diseases hosted by the house sparrow are also present in humans and domestic animals, for which the house sparrow acts as a reservoir host.[178] Arboviruses such as the West Nile virus, which most commonly infect insects and mammals, survive winters in temperate areas by going dormant in birds such as the house sparrow.[175][179] A few records indicate disease extirpating house sparrow populations, especially from Scottish islands, but this seems to be rare.[180]

The house sparrow is infested by a number of external parasites, which usually cause little harm to adult sparrows. In Europe, the most common mite found on sparrows is Proctophyllodes, the most common ticks are Argas reflexus and Ixodes arboricola, and the most common flea on the house sparrow is Ceratophyllus gallinae. A number of chewing lice occupy different niches on the house sparrow's body. Menacanthus lice occur across the house sparrow's body, where they feed on blood and feathers, while Brueelia lice feed on feathers and Philopterus fringillae occurs on the head.[144]

Physiology

House sparrows express strong circadian rhythms of activity in the laboratory. They were among the first bird species to be seriously studied in terms of their circadian activity and photoperiodism, in part because of their availability and adaptability in captivity, but also because they can "find their way" and remain rhythmic in constant darkness.[181][182] Such studies have found that the pineal gland is a central part of the house sparrow's circadian system: removal of the pineal eliminates the circadian rhythm of activity,[183] and transplant of the pineal into another individual confers to this individual the rhythm phase of the donor bird.[184] The suprachiasmatic nuclei of the hypothalamus have also been shown to be an important component of the circadian system of house sparrows.[185] The photoreceptors involved in the synchronisation of the circadian clock to the external light-dark cycle are located in the brain and can be stimulated by light reaching them directly though the skull, as revealed by experiments in which blind sparrows, which normally can still synchronise to the light-dark cycle, failed to do so once India ink was injected as a screen under the skin on top of their skulls.[186]

Similarly, even when blind, house sparrows continue to be photoperiodic, i.e. show reproductive development when the days are long, but not when the days are short. This response is stronger when the feathers on top of the head are plucked, and is eliminated when India ink is injected under the skin at the top of the head, showing that the photoreceptors involved in the photoperiodic response to day length are located inside the brain.[187]

House sparrows have also been used in studies of nonphotic entrainment (i.e. synchronisation to an external cycle other than light and dark): for example, in constant darkness, a situation in which the birds would normally reveal their endogenous, non-24-hour, "free-running" rhythms of activity, they instead show 24-hour periodicity if they are exposed to two hours of chirp playbacks every 24 hours, matching their daily activity onsets with the daily playback onsets.[188] House sparrows in constant dim light can also be entrained to a daily cycle based on the presence of food.[189] Finally, house sparrows in constant darkness can be entrained to a cycle of high and low temperature, but only if the difference between the two temperatures is large (38 versus 6 °C); some of the tested sparrows matched their activity to the warm phase, and others to the cold phase.[190]

Relationships with humans

The house sparrow is closely associated with humans. They are believed to have become associated with humans around 10,000 years ago. Subspecies P. d. bactrianus is least associated with humans and considered to be evolutionarily closer to the ancestral noncommensal populations.[191] Usually, it is regarded as a pest, since it consumes agricultural products and spreads disease to humans and their domestic animals.[192] Even birdwatchers often hold it in little regard because of its molestation of other birds.[77] In most of the world, the house sparrow is not protected by law. Attempts to control house sparrows include the trapping, poisoning, or shooting of adults; the destruction of their nests and eggs; or less directly, blocking nest holes and scaring off sparrows with noise, glue, or porcupine wire.[193] However, the house sparrow can be beneficial to humans, as well, especially by eating insect pests, and attempts at the large-scale control of the house sparrow have failed.[39]

The house sparrow has long been used as a food item. From around 1560 to at least the 19th century in northern Europe, earthenware "sparrow pots" were hung from eaves to attract nesting birds so the young could be readily harvested. Wild birds were trapped in nets in large numbers, and sparrow pie was a traditional dish, thought, because of the association of sparrows with lechery, to have aphrodisiac properties. Sparrows were also trapped as food for falconers' birds and zoo animals. In the early part of the 20th century, sparrow clubs culled many millions of birds and eggs in an attempt to control numbers of this perceived pest, but with only a localised impact on numbers.[194] House sparrows have been kept as pets at many times in history, though they have no bright plumage or attractive songs, and raising them is difficult.[195]

Status

The house sparrow has an extremely large range and population, and is not seriously threatened by human activities, so it is assessed as least concern for conservation on the IUCN Red List.[1] However, populations have been declining in many parts of the world.[196][197][198] These declines were first noticed in North America, where they were initially attributed to the spread of the house finch, but have been most severe in Western Europe.[199][200] Declines have not been universal, as no serious declines have been reported from Eastern Europe, but have even occurred in Australia, where the house sparrow was introduced recently.[201]

In Great Britain, populations peaked in the early 1970s,[202] but have since declined by 68% overall,[203] and about 90% in some regions.[204][205] In London, the house sparrow almost disappeared from the central city.[204] The numbers of house sparrows in the Netherlands have dropped in half since the 1980s,[94] so the house sparrow is even considered an endangered species.[206] This status came to widespread attention after a female house sparrow, referred to as the "Dominomus", was killed after knocking down dominoes arranged as part of an attempt to set a world record.[207] These declines are not unprecedented, as similar reductions in population occurred when the internal combustion engine replaced horses in the 1920s and a major source of food in the form of grain spillage was lost.[208][209]

Various causes for the dramatic decreases in population have been proposed, including predation, in particular by Eurasian sparrowhawks;[210][211][212] electromagnetic radiation from mobile phones;[213] and diseases.[214] A shortage of nesting sites caused by changes in urban building design is probably a factor, and conservation organisations have encouraged the use of special nest boxes for sparrows.[214][215][216][217] A primary cause of the decline seems to be an insufficient supply of insect food for nestling sparrows.[214][218] Declines in insect populations result from an increase of monoculture crops, the heavy use of pesticides,[219][220][221] the replacement of native plants in cities with introduced plants and parking areas,[222][223] and possibly the introduction of unleaded petrol, which produces toxic compounds such as methyl nitrite.[224]

Protecting insect habitats on farms,[225][226] and planting native plants in cities benefit the house sparrow, as does establishing urban green spaces.[227][228] To raise awareness of threats to the house sparrow, World Sparrow Day has been celebrated on 20 March across the world since 2010.[229] Over the recent years, the house sparrow population has been on the decline in many Asian countries, and this decline is quite evident in India. To promote the conservation of these birds, in 2012, the house sparrow was declared as the state bird of Delhi.[230]

Cultural associations

To many people across the world, the house sparrow is the most familiar wild animal and, because of its association with humans and familiarity, it is frequently used to represent the common and vulgar, or the lewd.[231] One of the reasons for the introduction of house sparrows throughout the world was their association with the European homeland of many immigrants.[81] Birds usually described later as sparrows are referred to in many works of ancient literature and religious texts in Europe and western Asia. These references may not always refer specifically to the house sparrow, or even to small, seed-eating birds, but later writers who were inspired by these texts often had the house sparrow in mind.[39][231][232] In particular, sparrows were associated by the ancient Greeks with Aphrodite, the goddess of love, due to their perceived lustfulness, an association echoed by later writers such as Chaucer and Shakespeare.[39][195][231][233] Jesus's use of "sparrows" as an example of divine providence in the Gospel of Matthew[234] also inspired later references, such as that in Shakespeare's Hamlet[231] and the Gospel hymn His Eye Is on the Sparrow.[235]

|

|

References

- 1 2 BirdLife International (2013). "Passer domesticus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2013.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 12 March 2014.

- ↑ Summers-Smith 1988, pp. 307–313

- 1 2 3 4 Summers-Smith 1988, pp. 116–117

- 1 2 3 4 "House Sparrow". All About Birds. Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Archived from the original on 8 December 2010.

- ↑ Clement, Harris & Davis 1993, p. 443

- 1 2 Summers-Smith 1988, pp. 118–121

- 1 2 Johnston, Richard F.; Selander, Robert K (May–June 1973). "Evolution in the House Sparrow. III. Variation in Size and Sexual Dimorphism in Europe and North and South America". The American Naturalist. 107 (955): 373–390. JSTOR 2459538. doi:10.1086/282841.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Groschupf, Kathleen (2001). "Old World Sparrows". In Elphick, Chris; Dunning, John B., Jr.; Sibley, David. The Sibley Guide to Bird Life and Behaviour. London: Christopher Helm. pp. 562–564. ISBN 0-7136-6250-6.

- ↑ Felemban, Hassan M. (1997). "Morphological differences among populations of house sparrows from different altitudes in Saudi Arabia" (PDF). The Wilson Bulletin. 109 (3): 539–544.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Clement, Harris & Davis 1993, p. 444

- ↑ Anderson 2006, pp. 202–203

- ↑ Anderson 2006, pp. 224–225, 244–245

- ↑ Summers-Smith 1963, pp. 26–30

- ↑ Cramp & Perrins 1994, p. 291

- ↑ Summers-Smith 1963, p. 101

- 1 2 Summers-Smith 1963, pp. 30–31

- ↑ Summers-Smith 1963, pp. 31–32

- ↑ Summers-Smith 1988, p. 254

- 1 2 3 4 Vaurie, Charles; Koelz, Walter. "Notes on some Ploceidae from western Asia". American Museum Novitates (1406). hdl:2246/2345.

- 1 2 3 Summers-Smith 1988, p. 117

- ↑ Snow & Perrins 1998, pp. 1061–1064

- ↑ Clement, Harris & Davis 1993, p. 445

- ↑ Roberts 1992, pp. 472–477

- ↑ Mullarney et al. 1999, pp. 342–343

- ↑ Clement, Harris & Davis 1993, pp. 463–465

- 1 2 Summers-Smith 1988, pp. 121–122

- ↑ Linnaeus 1758, p. 183

- 1 2 Summers-Smith 1988, pp. 114–115

- ↑ Brisson 1760, p. 36

- ↑

Newton, Alfred (1911). "Sparrow". In Chisholm, Hugh. Encyclopædia Britannica. 25 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Newton, Alfred (1911). "Sparrow". In Chisholm, Hugh. Encyclopædia Britannica. 25 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. - ↑ Summers-Smith 1988, p. 13

- ↑ Jobling 2009, p. 138

- ↑ Saikku, Mikko (2004). "House Sparrow". In Krech, Shepard; McNeill, John Robert; Merchant, Carolyn. Encyclopedia of World Environmental History. 3. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-93734-5.

- ↑ Turcotte & Watts 1999, p. 429

- ↑ Sibley & Monroe 1990, pp. 669–670

- ↑ Lockwood 1984, pp. 114–146

- ↑ Swainson 1885, pp. 60–62

- ↑ Carver 1987, pp. 162, 199

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Summers-Smith, J. Denis (2009). "Family Passeridae (Old World Sparrows)". In del Hoyo, Josep; Elliott, Andrew; Christie, David. Handbook of the Birds of the World. Volume 14: Bush-shrikes to Old World Sparrows. Barcelona: Lynx Edicions. ISBN 978-84-96553-50-7.

- ↑ Summers-Smith 1988, pp. 253–254

- ↑ Arnaiz-Villena, Antonio; Gómez-Prieto, Pablo; Ruiz-de-Valle, Valentin (2009). "Phylogeography of finches and sparrows". Nova Science Publishers.

- ↑ Allende, Luis M.; et al. (2001). "The Old World sparrows (genus Passer) phylogeography and their relative abundance of nuclear mtDNA pseudogenes" (PDF). Journal of Molecular Evolution. 53 (2): 144–154. PMID 11479685. doi:10.1007/s002390010202. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 July 2011.

- ↑ González, Javier; Siow, Melanie; Garcia-del-Rey, Eduardo; Delgado, Guillermo; Wink, Michael (2008). Phylogenetic Relationships of the Cape Verde Sparrow based on Mitochondrial and Nuclear DNA (PDF). Systematics 2008, Göttingen. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 July 2011.

- ↑ Summers-Smith 1988, p. 164

- ↑ Summers-Smith 1988, p. 172

- ↑ Anderson 2006, p. 16

- ↑ Summers-Smith 1988, pp. 126–127

- 1 2 3 4 Töpfer, Till (2006). "The Taxonomic Status of the Italian Sparrow – Passer italiae (Vieillot 1817): Speciation by Stabilised Hybridisation? A Critical Analysis". Zootaxa. 1325: 117–145. ISSN 1175-5334.

- ↑ Metzmacher, M. (1986). "Moineaux domestiques et Moineaux espagnols, Passer domesticus et P. hispaniolensis, dans une région de l'ouest algérien : analyse comparative de leur morphologie externe". Le Gerfaut (in French and English). 76: 317–334.

- ↑ Anderson 2006, pp. 13–18, 25–26

- ↑ Summers-Smith 1988, pp. 121–126

- ↑ Summers-Smith 1988, pp. 169–170

- ↑ Summers-Smith 1992, pp. 22, 27

- ↑ Gavrilov, E. I. (1965). "On hybridisation of Indian and House Sparrows". Bulletin of the British Ornithologists' Club. 85: 112–114.

- 1 2 Oberholser 1974, p. 1009

- ↑ Johnston, Richard F.; Selander, Robert K. (March 1971). "Evolution in the House Sparrow. II. Adaptive Differentiation in North American Populations". Evolution. Society for the Study of Evolution. 25 (1): 1–28. JSTOR 2406496. doi:10.2307/2406496.

- ↑ Packard, Gary C. (March 1967). "House Sparrows: Evolution of Populations from the Great Plains and Colorado Rockies". Systematic Zoology. Society of Systematic Biologists. 16 (1): 73–89. JSTOR 2411519. doi:10.2307/2411519.

- ↑ Johnston, R. F.; Selander, R. K. (1 May 1964). "House Sparrows: Rapid Evolution of Races in North America". Science. 144 (3618): 548–550. PMID 17836354. doi:10.1126/science.144.3618.548.

- ↑ Selander, Robert K.; Johnston, Richard F. (1967). "Evolution in the House Sparrow. I. Intrapopulation Variation in North America" (PDF). The Condor. Cooper Ornithological Society. 69 (3): 217–258. JSTOR 1366314. doi:10.2307/1366314.

- ↑ Hamilton, Suzanne; Johnston, Richard F. (April 1978). "Evolution in the House Sparrow—VI. Variability and Niche Width" (PDF). The Auk. 95 (2): 313–323.

- ↑ Baker, Allan J. (July 1980). "Morphometric Differentiation in New Zealand Populations of the House Sparrow (Passer domesticus)". Evolution. Society for the Study of Evolution. 34 (4): 638–653. JSTOR 2408018. doi:10.2307/2408018.

- ↑ Summers-Smith 1988, pp. 133–135

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Summers-Smith 1988, pp. 126–128

- 1 2 3 Mackworth-Praed & Grant 1955, pp. 870–871

- ↑ Cramp & Perrins 1994, p. 289

- ↑ Vaurie, Charles (1956). "Systematic notes on Palearctic birds. No. 24, Ploceidae, the genera Passer, Petronia, and Montifringilla". American Museum Novitates (1814). hdl:2246/5394.

- ↑ Summers-Smith 1988, p. 134

- ↑ Anderson 2006, pp. 5, 9–12

- ↑ Summers-Smith 1988, pp. 129–137, 280–283

- 1 2 Anderson 2006, p. 5

- ↑ Summers-Smith 1963, pp. 171–173

- ↑ Anderson 2006, p. 22

- ↑ Summers-Smith 1988, pp. 293–296

- ↑ Martin, Lynn B., II; Fitzgerald, Lisa (2005). "A taste for novelty in invading house sparrows, Passer domesticus". Behavioral Ecology. 16 (4): 702–707. doi:10.1093/beheco/ari044.

- ↑ Lee, Kelly A.; Martin, Lynn B., II; Wikelski, Martin C. (2005). "Responding to inflammatory challenges is less costly for a successful avian invader, the house sparrow (Passer domesticus), than its less-invasive congener" (PDF). Oecologia. 145 (2): 244–251. PMID 15965757. doi:10.1007/s00442-005-0113-5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 September 2006.

- ↑ Blakers, Davies & Reilly 1984, p. 586

- 1 2 3 4 Franklin, K. (2007). "The House Sparrow: Scourge or Scapegoat?". Naturalist News. Audubon Naturalist Society. Archived from the original on 4 March 2009. Retrieved 17 December 2008.

- ↑ Clergeau, Philippe; Levesque, Anthony; Lorvelec, Olivier (2004). "The Precautionary Principle and Biological Invasion: The Case of the House Sparrow on the Lesser Antilles". International Journal of Pest Management. 50 (2): 83–89. doi:10.1080/09670870310001647650.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Summers-Smith, J. D. (1990). "Changes in distribution and habitat utilisation by members of the genus Passer". In Pinowski, J.; Summers-Smith, J. D. Granivorous birds in the agricultural landscape. Warszawa: Pánstwowe Wydawnictom Naukowe. pp. 11–29. ISBN 83-01-08460-X.

- ↑ Barrows 1889, p. 17

- 1 2 Healy, Michael; Mason, Travis V.; Ricou, Laurie (2009). "'hardy/unkillable clichés': Exploring the Meanings of the Domestic Alien, Passer domesticus". Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and Environment. Oxford University Press. 16 (2): 281–298. doi:10.1093/isle/isp025.

- ↑ Marshall, Peyton. "The Truth About Sparrows". Opinionator. Retrieved 2016-04-08.

- ↑ Massam, Marion. "Sparrows" (PDF). Farmnote. Agriculture Western Australia (117/99). ISSN 0726-934X. Retrieved 1 February 2009.

- ↑ Anderson 2006, p. 25

- ↑ Brooke, R. K. (1997). "House Sparrow". In Harrison, J. A.; Allan, D. G.; Underhill, L. G.; Herremans, M.; Tree, A. J.; Parker, V.; Brown, C. J. The Atlas of Southern African Birds (PDF). 1. BirdLife South Africa.

- ↑ Lever 2005, pp. 210–212

- ↑ Restall, Rodner & Lentino 2007, p. 777

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Summers-Smith 1988, pp. 137–138

- ↑ Anderson 2006, pp. 424–425

- ↑ Hobbs, J. N. (1955). "House Sparrow breeding away from Man" (PDF). The Emu. 55 (4): 202. doi:10.1071/MU955202.

- ↑ Wodzicki, Kazimierz (May 1956). "Breeding of the House Sparrow away from Man in New Zealand" (PDF). Emu. 54: 146–147. doi:10.1071/mu956143e.

- ↑ Summers-Smith 1992, pp. 128–132

- ↑ Brooke, R. K. (January 1973). "House Sparrows Feeding at Night in New York" (PDF). The Auk. 90 (1): 206.

- 1 2 van der Poel, Guus (29 January 2001). "Concerns about the population decline of the House Sparrow Passer domesticus in the Netherlands". Archived from the original on 13 February 2005.

- ↑ Summers-Smith 1988, p. 129

- ↑ Minock, Michael E. (1969). "Salinity Tolerance and Discrimination in House Sparrows (Passer domesticus)" (PDF). The Condor. 71 (1): 79–80. JSTOR 1366060. doi:10.2307/1366060.

- 1 2 Walsberg, Glenn E. (1975). "Digestive Adaptations of Phainopepla nitens Associated with the Eating of Mistletoe Berries" (PDF). The Condor. Cooper Ornithological Society. 77 (2): 169–174. JSTOR 1365787. doi:10.2307/1365787.

- ↑ Melville, David S.; Carey, Geoff J. (998). "Syntopy of Eurasian Tree Sparrow Passer montanus and House Sparrow P. domesticus in Inner Mongolia, China" (PDF). Forktail. 13: 125. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 June 2011. Retrieved 10 September 2010.

- ↑ Summers-Smith 1988, p. 228

- ↑ BirdLife International (2008). "Passer domesticus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2008. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Archived from the original on 11 February 2009.

- ↑ Anderson 2006, p. 247

- 1 2 3 4 5 Summers-Smith 1988, pp. 139–142

- ↑ McGillivray, W. Bruce (1980). "Communal Nesting in the House Sparrow" (PDF). Journal of Field Ornithology. 51 (4): 371–372.

- ↑ Johnston, Richard F. (1969). "Aggressive Foraging Behavior in House Sparrows" (PDF). The Auk. 86 (3): 558–559. doi:10.2307/4083421.

- ↑ Kalinoski, Ronald (1975). "Intra- and Interspecific Aggression in House Finches and House Sparrows" (PDF). The Condor. 77 (4): 375–384. JSTOR 1366086. doi:10.2307/1366086.

- ↑ Reebs, S. G.; Mrosovsky, N. (1990). "Photoperiodism in house sparrows: testing for induction with nonphotic zeitgebers". Physiological Zoology. 63: 587–599.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Lowther, Peter E.; Cink, Calvin L. (2006). Poole, A., ed. "House Sparrow (Passer domesticus)". The Birds of North America Online. Retrieved 21 April 2010.

- ↑ Potter, E. F. (1970). "Anting in wild birds, its frequency and probable purpose" (PDF). Auk. 87 (4): 692–713. doi:10.2307/4083703.

- 1 2 3 Anderson 2006, pp. 273–275

- ↑ Anderson 2006, p. 246

- ↑ Kalmus, H. (1984). "Wall clinging: energy saving by the House Sparrow Passer domesticus". Ibis. 126 (1): 72–74. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1984.tb03667.x.

- ↑ Stidolph, R. D. H. (1974). "The Adaptable House Sparrow". Notornis. 21 (1): 88.

- ↑ Anderson 2006, pp. 279–281

- ↑ Gionfriddo, James P.; Best, Louis B. (1995). "Grit Use by House Sparrows: Effects of Diet and Grit Size" (PDF). The Condor. 97 (1): 57–67. JSTOR 1368983. doi:10.2307/1368983.

- ↑ Summers-Smith 1963, pp. 34–35

- 1 2 3 Summers-Smith 1988, pp. 159–161

- ↑ Summers-Smith 1963, p. 33

- ↑ Gavett, Ann P.; Wakeley, James S. (1986). "Diets of House Sparrows in Urban and Rural Habitats" (PDF). The Wilson Bulletin. 98.

- ↑ Summers-Smith 1963, pp. 35, 38–39

- ↑ Vincent 2005, pp. 2–3

- 1 2 Anderson 2006, pp. 276–279

- ↑ Anderson, Ted R. (1977). "Reproductive Responses of Sparrows to a Superabundant Food Supply" (PDF). The Condor. Cooper Ornithological Society. 79 (2): 205–208. JSTOR 1367163. doi:10.2307/1367163.

- ↑ Ivanov, Bojidar (1990). "Diet of House Sparrow [Passer domesticus (L.)] nestlings on a livestock farm near Sofia, Bulgaria". In Pinowski, J.; Summers-Smith, J. D. Granivorous birds in the agricultural landscape. Warszawa: Pánstwowe Wydawnictom Naukowe. pp. 179–197. ISBN 83-01-08460-X.

- ↑ Schnell, G. D.; Hellack, J. J. (1978). "Flight speeds of Brown Pelicans, Chimney Swifts, and other birds". Bird-Banding. 49 (2): 108–112. JSTOR 4512338. doi:10.2307/4512338.

- ↑ Broun, Maurice (1972). "Apparent migratory behavior in the House Sparrow" (PDF). The Auk. 89 (1): 187–189. doi:10.2307/4084073.

- ↑ Waddington, Don C.; Cockrem, John F. (1987). "Homing Ability of the House Sparrow". Notornis. 34 (1).

- ↑ Anderson 2006, pp. 135–136

- ↑ Hatch, Margret I.; Westneat, David F. (2007). "Age-related patterns of reproductive success in house sparrows Passer domesticus". Journal of Avian Biology. 38 (5): 603–611. doi:10.1111/j.0908-8857.2007.04044.x.

- ↑ Whitfield-Rucker, M.; Cassone, V. M. (2000). "Photoperiodic Regulation of the Male House Sparrow Song Control System: Gonadal Dependent and Independent Mechanisms". General and Comparative Endocrinology. 118 (1): 173–183. PMID 10753579. doi:10.1006/gcen.2000.7455.

- ↑ Birkhead 2012, pp. 47–48

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Summers-Smith 1988, pp. 144–147

- 1 2 3 Summers-Smith 1988, pp. 142–143

- ↑ Brackbill, Hervey (1969). "Two Male House Sparrows Copulating on Ground with Same Female" (PDF). The Auk. 86 (1): 146. doi:10.2307/4083563.

- ↑ Anderson 2006, pp. 141–142

- ↑ Anderson 2006, p. 145

- ↑ Anderson 2006, pp. 143–144

- ↑ Anderson, T. R. (1990). "Excess females in a breeding population of House Sparrows [Passer domesticus (L.)]". In Pinowski, J.; Summers-Smith, J. D. Granivorous birds in the agricultural landscape. Warszawa: Pánstwowe Wydawnictom Naukowe. pp. 87–94. ISBN 83-01-08460-X.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Summers-Smith 1963, pp. 52–57

- 1 2 3 4 Indykiewicz, Piotr (1990). "Nest-sites and nests of House Sparrow [Passer domesticus (L.)] in an urban environment". In Pinowski, J.; Summers-Smith, J. D. Granivorous birds in the agricultural landscape. Warszawa: Pánstwowe Wydawnictom Naukowe. pp. 95–121. ISBN 83-01-08460-X.

- ↑ Gowaty, Patricia Adair (Summer 1984). "House Sparrows Kill Eastern Bluebirds" (PDF). Journal of Field Ornithology. 55 (3): 378–380. Retrieved 1 October 2009.

- ↑ Haverschmidt 1949, pp. 33–34

- ↑ Morris & Tegetmeier 1896, pp. 8–9

- ↑ Jansen, R. R. (1983). "House Sparrows build roost nests". The Loon. 55: 64–65. ISSN 0024-645X.

- 1 2 Summers-Smith 1963, pp. 131–132

- ↑ "Neottiophilum praeustum". NatureSpot. Retrieved 10 January 2012.

- ↑ Sustek, Zbyšek; Hokntchova, Daša (1983). "The beetles (Coleoptera) in the nests of Delichon urbica in Slovakia" (PDF). Acta Rerum Naturalium Musei Nationalis Slovaci, Bratislava. XXIX: 119–134. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 August 2011.

- 1 2 3 Summers-Smith 1988, pp. 148–149

- ↑ Anderson 2006, pp. 157–172

- 1 2 Anderson 2006, pp. 145–146

- ↑ Anderson 2006, p. 319

- ↑ Davies 2000, p. 55

- ↑ Stoner, Dayton (December 1939). "Parasitism of the English Sparrow on the Northern Cliff Swallow" (PDF). Wilson Bulletin. 51 (4).

- ↑ "BTO Bird facts: House Sparrow". British Trust for Ornithology. Retrieved 24 November 2009.

- ↑ Paganelli, C. V.; Olszowka, A.; Ali, A. (1974). "The Avian Egg: Surface Area, Volume, and Density" (PDF). The Condor. Cooper Ornithological Society. 76 (3): 319–325. JSTOR 1366345. doi:10.2307/1366345.

- ↑ Ogilvie-Grant 1912, pp. 201–204

- ↑ Hume & Oates 1890, pp. 169–151

- ↑ Anderson 2006, pp. 175–176

- ↑ Anderson 2006, pp. 173–175

- ↑ Anderson 2006, pp. 176–177

- ↑ Nice, Margaret Morse (1953). "The Question of Ten-day Incubation Periods" (PDF). The Wilson Bulletin. 65 (2): 81–93.

- 1 2 3 Summers-Smith 1988, pp. 149–150

- 1 2 Glutz von Blotzheim & Bauer 1997, p. 60ff

- 1 2 3 Glutz von Blotzheim & Bauer 1997, pp. 105–115

- ↑ "Der es von den Dächern pfeift: Der Haussperling (Passer domesticus)" (in German). nature-rings.de.

- ↑ Giebing, Manfred (31 October 2006). "Der Haussperling: Vogel des Jahres 2002" (in German). Archived from the original on 22 November 2007.

- ↑ Glutz von Blotzheim & Bauer 1997, pp. 79–89

- ↑ Summers-Smith 1988, pp. 154–155

- ↑ Summers-Smith 1988, pp. 137–141

- ↑ "European Longevity Records". EURING: The European Union for Bird Ringing. Retrieved 24 November 2009.

- ↑ "AnAge entry for Passer domesticus". AnAge: the Animal Ageing and Longevity Database. Retrieved 1 February 2010.

- ↑ Anderson 2006, pp. 333–336

- 1 2 Anderson 2006, pp. 304–306

- ↑ Summers-Smith 1992, pp. 30–33

- ↑ Erritzoe, J.; Mazgajski, T. D.; Rejt, L. (2003). "Bird casualties on European roads – a review" (PDF). Acta Ornithologica. 38 (2): 77–93. doi:10.3161/068.038.0204.

- 1 2 3 Anderson 2006, pp. 311–317

- ↑ Summers-Smith 1963, p. 128

- ↑ van Riper, Charles III; van Riper, Sandra G.; Hansen, Wallace R. (2002). "Epizootiology and Effect of Avian Pox on Hawaiian Forest Birds". The Auk. 119 (4): 929–942. ISSN 0004-8038. doi:10.1642/0004-8038(2002)119[0929:EAEOAP]2.0.CO;2.

- ↑ Anderson 2006, pp. 427–429

- ↑ Young, Emma (1 November 2000). "Sparrow suspect". New Scientist. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ↑ Summers-Smith 1963, p. 129

- ↑ Menaker, M. (1972). "Nonvisual light reception". Scientific American. 226 (3): 22–29. Bibcode:1972SciAm.226c..22M. PMID 5062027. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0372-22.

- ↑ Binkley, S. (1990). The clockwork sparrow: Time, clocks, and calendars in biological organisms. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

- ↑ Gaston, S.; Menaker, M. (1968). "Pineal function: The biological clock in the sparrow". Science. 160 (3832): 1125–1127. Bibcode:1968Sci...160.1125G. PMID 5647435. doi:10.1126/science.160.3832.1125.

- ↑ Zimmerman, W.; Menaker, M. (1979). "The pineal gland: A pacemaker within the circadian system of the house sparrow". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 76: 999–1003. doi:10.1073/pnas.76.2.999.

- ↑ Takahashi, J. S.; Menaker, M. (1982). "Role of the suprachiasmatic nuclei in the circadian system of the house sparrow, Passer domesticus". Journal of Neuroscience. 2 (6): 815–828. PMID 7086486.

- ↑ McMillan, J. P.; Keatts, H. C.; Menaker, M. (1975). "On the role of eyes and brain photoreceptors in the sparrow: Entrainment to light cycles". Journal of Comparative Physiology. 102 (3): 251–256. doi:10.1007/BF01464359.

- ↑ Menaker, M.; Roberts, R.; Elliott, J.; Underwood, H. (1970). "Extraretinal light perception in the sparrow, III. The eyes do not participate in photoperiodic photoreception". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 67: 320––325. Bibcode:1970PNAS...67..320M. doi:10.1073/pnas.67.1.320.

- ↑ Reebs, S.G. (1989). "Acoustical entrainment of circadian activity rhythms in house sparrows: Constant light is not necessary". Ethology. 80: 172–181. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0310.1989.tb00737.x.

- ↑ Hau, M.; Gwinner, E. (1992). "Circadian entrainment by feeding cycles in house sparrows, Passer domesticus". Journal of Comparative Physiology A. 170 (4): 403–409. doi:10.1007/BF00191457.

- ↑ Eskin, A. (1971). "Some properties of the system controlling the circadian activity rhythm of sparrows". In Menaker, M. Biochronometry. Washington: National Academy of Sciences. pp. 55–80.

- ↑ Sætre, G.-P.; et al. (2012). "Single origin of human commensalism in the house sparrow". Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 25 (4): 788–796. PMID 22320215. doi:10.1111/j.1420-9101.2012.02470.x.

- ↑ Anderson 2006, pp. 425–429

- ↑ Invasive Species Specialist Group. "ISSG Database: Ecology of Passer domesticus". Retrieved 16 January 2009.

- ↑ Cocker & Mabey 2005, pp. 436–443

- 1 2 Summers-Smith 2005, pp. 29–35

- ↑ "Even sparrows don't want to live in cities anymore". Times of India. 13 June 2005. Archived from the original on 9 August 2011.

- ↑ Daniels, R. J. Ranjit (2008). "Can we save the sparrow?" (PDF). Current Science. 95 (11): 1527–1528. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 September 2011.

- ↑ De Laet, J.; Summers-Smith, J. D. (2007). "The status of the urban house sparrow Passer domesticus in north-western Europe: a review". Journal of Ornithology. 148 (Supplement 2): 275–278. doi:10.1007/s10336-007-0154-0.

- ↑ Anderson 2006, p. 320

- ↑ Summers-Smith, J. Denis (2005). "Changes in the House Sparrow Population in Britain" (PDF). International Studies on Sparrows. 5: 23–37. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 February 2010.

- ↑ Anderson 2006, pp. 229–300

- ↑ Summers-Smith 1988, pp. 157–158, 296

- ↑ "Sparrow numbers 'plummet by 68%'". BBC News. 20 November 2008. Retrieved 6 December 2009.

- 1 2 McCarthy, Michael (16 May 2000). "It was once a common or garden bird. Now it's not common or in your garden. Why?". The Independent. Retrieved 12 December 2009.

- ↑ "House sparrow". ARKive. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- ↑ Gould, Anne Blair (29 November 2004). "House sparrow dwindling". Radio Nederland Wereldomroep. Archived from the original on 27 November 2005.

- ↑ "Sparrow death mars record attempt". BBC News. 19 November 2005. Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- ↑ Summers-Smith 1988, p. 156

- ↑ Bergtold, W. H. (April 1921). "The English Sparrow (Passer domesticus) and the Automobile" (PDF). The Auk. 38 (2): 244–250. doi:10.2307/4073887.

- ↑ MacLeod, Ross; Barnett, Phil; Clark, Jacquie; Cresswell, Will (23 March 2006). "Mass-dependent predation risk as a mechanism for house sparrow declines?". Biology Letters. 2 (1): 43–46. PMC 1617206

. PMID 17148322. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2005.0421.

. PMID 17148322. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2005.0421. - ↑ Bell, Christopher P.; Baker, Sam W.; Parkes, Nigel G.; Brooke, M. de L.; Chamberlain, Dan E. (2010). "The Role of the Eurasian Sparrowhawk (Accipiter nisus) in the Decline of the House Sparrow (Passer domesticus) in Britain". The Auk. 127 (2): 411–420. doi:10.1525/auk.2009.09108.

- ↑ McCarthy, Michael (19 August 2010). "Mystery of the vanishing sparrows still baffles scientists 10 years on". The Independent. Retrieved 24 September 2011.

- ↑ Balmori, Alfonso; Hallberg, Örjan (2007). "The Urban Decline of the House Sparrow (Passer domesticus): A Possible Link with Electromagnetic Radiation". Electromagnetic Biology and Medicine. 26 (2): 141–151. PMID 17613041. doi:10.1080/15368370701410558.

- 1 2 3 McCarthy, Michael (20 November 2008). "Mystery of the vanishing sparrow". The Independent. Retrieved 17 January 2009.

- ↑ Vincent, Kate; Baker Shepherd Gillespie (2006). The provision of birds in buildings; turning buildings into bird-friendly habitats (PowerPoint presentation). Ecobuild exhibition. Retrieved 10 January 2010.

- ↑ De Laet, Jenny; Summers-Smith, Denis; Mallord, John (2009). "Meeting on the Decline of the Urban House Sparrow Passer domesticus: Newcastle 2009 (24–25 Feb)" (PDF). International Studies on Sparrows. 33: 17–32. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 July 2011.

- ↑ Butler, Daniel (2 February 2009). "Helping birds to nest on Valentine's Day". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- ↑ Peach, W. J.; Vincent, K. E.; Fowler, J. A.; Grice, P. V. (2008). "Reproductive success of house sparrows along an urban gradient" (PDF). Animal Conservation. 11 (6): 1–11. doi:10.1111/j.1469-1795.2008.00209.x.

- ↑ Vincent 2005, pp. 265–270

- ↑ Vincent, Kate E.; Peach, Will; Fowler, Jim (2009). An investigation in to the breeding biology and nestling diet of the house sparrow in urban Britain (PowerPoint presentation). International Ornithological Congress. Retrieved 17 January 2009.

- ↑ Vincent, Kate E. (2009). Reproductive success of house sparrows along an urban gradient (PowerPoint presentation). LIPU – Passeri in crisis?. Pisa, Italy. Retrieved 17 January 2010.

- ↑ Clover, Charles (20 November 2008). "On the trail of our missing house sparrows". The Telegraph. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ↑ Smith, Lewis (20 November 2008). "Drivers and gardeners the secret behind flight of house sparrows". The Times. Retrieved 17 January 2009.

- ↑ Summers-Smith, J. Denis (September 2007). "Is unleaded petrol a factor in urban House Sparrow decline?". British Birds. 100: 558. ISSN 0007-0335.

- ↑ Hole, D. G.; et al. (2002). "Ecology and conservation of rural house sparrows". Ecology of Threatened Species. Royal Society for the Protection of Birds. Archived from the original on 3 January 2010. Retrieved 17 January 2010.

- ↑ Hole, David G.; Whittingham, M. J.; Bradbury, Richard B.; Anderson, Guy Q. A.; Lee, Patricia L. M.; Wilson, Jeremy D.; Krebs, John R. (29 August 2002). "Agriculture: Widespread local house-sparrow extinctions". Nature. 418 (6901): 931–932. PMID 12198534. doi:10.1038/418931a.

- ↑ Adam, David (20 November 2009). "Leylandii may be to blame for house sparrow decline, say scientists". The Guardian. Retrieved 17 January 2009.

- ↑ Mukherjee, Sarah (20 November 2008). "Making a garden sparrow-friendly". BBC News. Retrieved 17 January 2009.

- ↑ Sathyendran, Nita (21 March 2012). "Spare a thought for the sparrow". The Hindu. Retrieved 22 March 2012.

- ↑ "Save our sparrows". The Hindu. 11 March 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 Summers-Smith 1963, pp. 49, 215

- ↑ Shipley, A. E. (1899). "Sparrow". In Cheyne, Thomas Kelley; Black, J. Sutherland. Encyclopaedia Biblica. 4.

- ↑ "Sparrow". A Dictionary of Literary Symbols. 2007.

- ↑ Matthew 10:29-31

- ↑ Todd 2012, pp. 56–58

- ↑ Houlihan & Goodman 1986, pp. 136–137

- ↑ Wilkinson 1847, pp. 211–212

Works cited

- Anderson, Ted R. (2006). Biology of the Ubiquitous House Sparrow: from Genes to Populations. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-530411-X.

- Barrows, Walter B. (1889). "The English Sparrow (Passer domesticus) in North America, Especially in its Relations to Agriculture". United States Department of Agriculture, Division of Economic Ornithology and Mammalology Bulletin. Washington: Government Printing Office (1).

- Birkhead, Tim (2012). Bird Sense: What It's Like to Be a Bird. New York: Walker & Company. ISBN 978-0-8027-7966-3.

- Blakers, M.; Davies, S. J. J. F.; Reilly, P. N. (1984). The Atlas of Australian Birds. Melbourne University Press. ISBN 0-522-84285-2.

- Brisson, Mathurin Jacques (1760). Ornithologie ou Méthode contenant la division des oiseaux en Ordres, Sections, Genres, Especes & leurs Variétés: a Laquelle on a joint une Description exacte de chaque Espece, avec les Citations des Auteurs qui en ont traité, les Noms qu'ils leur ont donnés, ceux que leur ont donnés les différentes Nations, & les Noms vulgaires (in French). IV. Paris: Bauche.

- Carver, Craig M. (1987). American Regional Dialects: a Word Geography. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-10076-7.

- Cocker, Mark; Mabey, Richard (2005). Birds Britannica. London: Chatto & Windus. ISBN 0701169079.

- Clement, Peter; Harris, Alan; Davis, John (1993). Finches and Sparrows: an Identification Guide. London: Christopher Helm. ISBN 0-7136-8017-2.

- Cramp, S.; Perrins, C. M., eds. (1994). The Birds of the Western Palearctic. Volume 8, Crows to Finches. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Davies, Nick B. (2000). Cuckoos, Cowbirds, and Other Cheats. illustrated by David Quinn. London: T. & A. D. Poyser. ISBN 0-85661-135-2.

- Glutz von Blotzheim, U. N.; Bauer, K. M. (1997). Handbuch der Vögel Mitteleuropas, Band 14-I; Passeriformes (5. Teil). AULA-Verlag. ISBN 3-923527-00-4.

- Haverschmidt, François (1949). The Life of the White Stork. Leiden: E. J. Brill.

- Houlihan, Patrick E.; Goodman, Steven M. (1986). The Natural History of Egypt, Volume I: The Birds of Ancient Egypt. Warminster: Aris & Philips. ISBN 0-85668-283-7.

- Hume, Allan O.; Oates, Eugene William (1890). The Nests and Eggs of Indian Birds. II (2nd. ed.). London: R. H. Porter.

- Jobling, James A. (2009). Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. ISBN 1-4081-2501-3.

- Lever, Christopher (2005). Naturalised Birds of the World. T. & A. D. Poyser. ISBN 0-7136-7006-1.

- Linnaeus, Carolus (1758). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin). I (10th revised ed.). Holmius: Laurentius Salvius.

- Lockwood, W. B. (1984). The Oxford Book of British Bird Names. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-214155-4.

- Mackworth-Praed, C. W.; Grant, C. H. B. (1955). African Handbook of Birds. Series 1: Birds of Eastern and North Eastern Africa. 2. Toronto: Longmans, Green, and Co.

- Morris, F. O.; Tegetmeier, W. B. (1896). A Natural History of the Nests and Eggs of British Birds. II (4th. ed.).

- Mullarney, Killian; Svensson, Lars; Zetterstrom, Dan; Grant, Peter (1999). Collins Bird Guide (1st. ed.). London: HarperCollins. ISBN 0-00-219728-6.

- Oberholser, Harry C. (1974). The Bird Life of Texas. 2. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-292-70711-8.

- Ogilvie-Grant, W. R. (1912). Catalogue of the Collection of Birds' Eggs in the British Museum (Natural History) Volume V: Carinatæ (Passeriformes completed). London: Taylor and Francis.

- Restall, Robin; Rodner, Clemencia; Lentino, Miguel (2007). The Birds of Northern South America: An Identification Guide. I. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-10862-0.

- Roberts, Tom J. (1992). The Birds of Pakistan. Volume 2: Passeriformes: Pittas to Buntings. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-577405-1.

- Sibley, Charles Gald; Monroe, Burt Leavelle (1990). Distribution and Taxonomy of Birds of the World. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-04969-2.

- Snow, David; Perrins, Christopher M., editors (1998). The Birds of the Western Palearctic. 2 (Concise ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-854099-X.

- Summers-Smith, J. Denis (1963). The House Sparrow. New Naturalist (1st. ed.). London: Collins.

- Summers-Smith, J. Denis (1988). The Sparrows. illustrated by Robert Gillmor. Calton, Staffs, England: T. & A. D. Poyser. ISBN 0-85661-048-8.

- Summers-Smith, J. Denis (1992). In Search of Sparrows. illustrated by Euan Dunn. London: T. & A. D. Poyser. ISBN 0-85661-073-9.

- Summers-Smith, J. Denis (2005). On Sparrows and Man: A Love-Hate Relationship. Guisborough. ISBN 0-9525383-2-6.

- Swainson, William (1885). Provincial Names and Folk Lore of British Birds. London: Trübner and Co.

- Todd, Kim (2012). Sparrow. Animal. Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1-86189-875-3.

- Turcotte, William H.; Watts, David L. (1999). Birds of Mississippi. University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 1-57806-110-5.

- Vincent, Kate E. (October 2005). "Investigating the causes of the decline of the urban House Sparrow Passer domesticus population in Britain" (PDF). Retrieved 2 December 2009.

- Wilkinson, John Gardner (1847). The manners and customs of the ancient Egyptians. 5. Edinburgh: John Murray.

External links

- "House sparrow media". Internet Bird Collection.

- House sparrow media at ARKive

- House sparrow at the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds website

- Indian sparrow and house sparrow at Birds of Kazakhstan

- World Sparrow Day

- Save the Indian House Sparrow

- House sparrow photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)