English-language vowel changes before historic /r/

| History and description of |

| English pronunciation |

|---|

| Historical stages |

| General development |

| Development of vowels |

| Development of consonants |

| Variable features |

| Related topics |

In English, many vowel shifts only affect vowels followed by /r/ in rhotic dialects, or vowels that were historically followed by an /r/ that has since been elided in non-rhotic dialects. Most of them involve merging of vowel distinctions, so that fewer vowel phonemes occur before /r/ than in other positions in a word.

Overview

In rhotic dialects, /r/ is pronounced in most cases. In General American (GA), /r/ is pronounced as an approximant [ɹ] or [ɻ] in most positions, but after some vowels is pronounced as r-coloring. In Scottish English, /r/ is traditionally pronounced as a flap [ɾ] or trill [r], and there are no r-colored vowels.

In non-rhotic dialects like Received Pronunciation (RP), historic /r/ is elided at the end of a syllable, and if the preceding vowel is stressed, it undergoes compensatory lengthening or breaking (diphthongization). Thus, words that historically had /r/ often have long vowels or centering diphthongs ending in a schwa /ə/, or a diphthong followed by a schwa.

- earth: GA [ɚθ], RP [ɜːθ]

- here: GA [ˈhiɚ], RP [ˈhɪə̯]

- fire: GA [ˈfaɪɚ], RP [ˈfaɪə̯]

In most English dialects, there are vowel shifts only affecting vowels before /r/, or vowels that were historically followed by /r/. Vowel shifts before historical /r/ fall into two categories: mergers and splits. Mergers are more common, and therefore most English dialects have fewer vowel distinctions before historical /r/ than in other positions in a word.

In many North American dialects, there are ten or eleven stressed monophthongs; only five or six vowel contrasts are possible before a following /r/ in the same syllable (peer, pear, purr, par, pore, poor). Often, more contrasts exist when the /r/ is not in the same syllable; in some American dialects and in most native English dialects outside North America, for example, mirror and nearer do not rhyme, and some or all of marry, merry and Mary are pronounced distinctly. (In North America, these distinctions are most likely to occur in New York City, Philadelphia, some of Eastern New England [for some, including Boston], and in conservative Southern accents.) In many dialects, however, the number of contrasts in this position tends to be reduced, and the tendency seems to be towards further reduction. The difference in how these reductions have been manifested represents one of the greatest sources of cross-dialect variation.

Non-rhotic accents in many cases show mergers in the same positions as rhotic accents do, even though there is often no /r/ phoneme present. This results partly from mergers that occurred before the /r/ was lost, and partly from later mergers of the centering diphthongs and long vowels that resulted from the loss of /r/.

The phenomenon that occurs in many dialects of the United States is one of tense–lax neutralization,[1] where the normal English distinction between tense and lax vowels is eliminated.

In some cases, the quality of a vowel before /r/ is different from the quality of the vowel elsewhere. For example, in some dialects of American English the quality of the vowel in more typically does not occur except before /r/, and is somewhere in between the vowels of maw and mow. It is similar to the vowel of the latter word, but without the glide.

It is important to note however that different mergers occur in different dialects. Among United States accents, the Boston, Eastern New England and New York accents have the lowest degree of pre-rhotic merging. Some have observed that rhotic North American accents are more likely to have such merging than non-rhotic accents, but this cannot be said of rhotic British accents like Scottish English, which is firmly rhotic and yet many varieties have all the same vowel contrasts before /r/ as before any other consonant.

Mergers before intervocalic R

Most North American English dialects merge the lax vowels with the tense vowels before /r/. "marry" and "merry" have the same vowel as "mare", "mirror" has the same vowel as "mere", "forest" has the same vowel as "corn", and "hurry" has the same vowel as "stir" for these speakers. These mergers are typically resisted for nonrhotic North Americans and are largely absent in areas of the United States that were historically largely nonrhotic.

Hurry–furry merger

|

|

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

The hurry–furry merger occurs when the vowel /ʌ/ before intervocalic /r/ is merged with /ɝ/, as in many dialects of American English, but not in the Northeast and the South[2] or in dialects outside North America. Speakers with this merger pronounce hurry so that it rhymes with furry, and turret so that it rhymes with stir it.

Mary–marry–merry merger

|

Mary-marry-merry

Example of an American speaker without the Mary-marry-merry merger |

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

One of the best-known mergers of vowels before /r/ is the Mary–marry–merry merger,[3] which consists of a merging of the vowels /æ/ (as in the name Carrie or the word marry) and /ɛ/ (as in Kerry or merry) with historical /eɪ/ (as in Cary or Mary) whenever they are realised before intervocalic /r/ (the "r" sound when occurring between vowels).[4] This merger is fairly widespread, meaning completed or at a near-complete stage, in North American English,[sample 1] but rare in other varieties of English. The following variants are common in North America:

- The full Mary–marry–merry merger (also known, in context, as the three-way merger): This is found throughout much of the United States (particularly the American West) and in all of Canada except Montreal. This is found in about 57% of US English speakers, according to a 2003 dialect survey.[5]

- No merger whatsoever (also known, in context, as the three-way contrast): A lack of this merger in North America exists primarily in the Northeastern United States: most clearly documented in the accents of Philadelphia, New York City, and Rhode Island. 17% of Americans have no merger.[6][sample 2] In the Philadelphia accent, the three-way contrast is preserved, but merry tends to be merged with Murray; likewise ferry can be a homophone of furry. (See merry–Murray merger below.) The three-way contrast is found in about 17% of U.S. English speakers overall.[5]

- Mary–marry merger only: This is only found in about 16% of U.S. English speakers overall, particularly in the Northeast.[5]

- Mary–merry merger only: This is found among Anglophones in Montreal and in the American South, in about 9% of U.S. English speakers overall, particularly in the eastern half of the U.S.[5][7]

- merry-marry merger only: This merger is rare, found in only about 1% of U.S. English speakers.

The three are kept distinct outside of North America. In accents that do not have the merger, Mary has the a sound of mare, marry has the "short a" sound of mat, and merry has the "short e" sound of met. In modern RP, they are pronounced as [ˈmɛːɹi], [ˈmæɹi], and [ˈmɛɹi]; in Australian English as [ˈmeːɹi], [ˈmæɹi], and [ˈmeɹi]; in New Zealand English as [ˈmi̞əɹi], [ˈmɛɹi], and [ˈme̝ɹi]; in New York City English as [ˈmeɹi⁓ˈmɛəɹi], [ˈmæɹi], and [ˈmɛɹi]; in Philadelphia English, the same as New York except merry is [ˈmɛɹi⁓ˈmʌɹi]. There is plenty of variance in the distribution of the merger, with expatriate communities of these speakers being formed all over the country. The most common phonetic value of the merged vowel is [ɛ], so that, for example, Mary, marry, and merry for many Americans all become merged as [ˈmɛɹi].[8]

| /eər/ | /ær/ | /ɛr/ | IPA | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aaron1 | Aaron2 | Erin | ˈɛrən | with weak-vowel merger |

| airable | arable | errable | ˈɛrəbəl | |

| airer | - | error | ˈɛrər | |

| - | barrel | beryl | ˈbɛrəl | with weak-vowel merger before /l/ |

| - | Barry | berry | ˈbɛri | |

| - | Barry | bury | ˈbɛri | |

| Cary1 | Carrie | Kerry | ˈkɛri | |

| Cary1 | carry | Kerry | ˈkɛri | |

| Cary1 | Cary2 | Kerry | ˈkɛri | |

| dairy | - | Derry | ˈdɛri | |

| fairy | - | ferry | ˈfɛri | |

| - | Farrell | feral | ˈfɛrəl | with weak-vowel merger before /l/ |

| Gary1 | Gary2 | - | ˈɡɛri | |

| hairy | Harry | - | ˈhɛri | |

| Mary | marry | merry | ˈmɛri | |

| - | parish | perish | ˈpɛrɪʃ | |

| - | parry | Perry | ˈpɛri | |

| scary | - | skerry | ˈskɛri | |

| Tara | - | Terra | ˈtɛrə | |

| - | tarry | Terry | ˈtɛri | |

| vary | - | very | ˈvɛri |

Merry–Murray merger

The merry–Murray merger (sometimes called the ferry–furry merger, but that is only the case for speakers who also have the hurry–furry merger) is a merger of /ɛ/ and /ʌ/ before /r/ (both neutralized with syllabic r) is common in the Philadelphia accent.[9] This accent does not usually have the marry–merry merger. That is, "short a" /æ/ as in marry is a distinct unmerged class before /r/. Thus, merry and Murray are pronounced the same, but marry is distinct from this pair.

| /ɛr/ | /ʌr/ | IPA | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kerry | curry | ˈkʌri | |

| merry | Murray | ˈmʌri | |

| skerry | scurry | ˈskʌri |

Mirror–nearer merger

Another widespread merger is the mirror–nearer merger or Sirius–serious merger of /ɪ/ with /iː/ before intervocalic /r/ (in other words, the sound "r" when between vowels). The typical result of the merger is [i(ː)ɹ] or [i(ː)ɚ]. For speakers with this merger, common in general accents throughout North America, mirror and nearer rhyme, and Sirius is homophonous with serious. North Americans who do not merge these vowels often speak the more conservative northeastern or southern accents.

Mergers of /ɒr-/ and /ɔːr-/

Words that would have a stressed /ɒ/ before intervocalic /r/ in the UK's Received Pronunciation (RP) are treated differently in different varieties of North American English. As shown in the table below, in Canadian English, all of these are pronounced with [-ɔɹ-], as in cord (and thus merge with historic prevocalic /ɔːr/ in words like glory because of the horse–hoarse merger). In the accents of Philadelphia, southern New Jersey, and the Carolinas (and traditionally throughout the South), these words are pronounced among some with [-ɑɹ-], as in card (and thus merge with historic prevocalic /ɑːr/ in words like starry). In the accents of New York City, Long Island, and nearby parts of New Jersey, these words are pronounced with [ɒr] like in RP. However, this is met with hypercorrection of /ɑːr/, (thus still merging with historic prevocalic /ɑːr/ in starry).[10] On the other hand, the traditional Eastern New England accents (famously, the Rhode Island and Boston accents) these words are pronounced with [-ɒɹ-] without hypercorrection, just like in RP. Most of the rest of the United States (marked "General American" in the table), however, has a distinctive mixed system: while the majority of words are pronounced as in Canada, the four (sometimes five) words in the left-hand column are typically pronounced with [-ɑɹ-];[11] and the East Coast regions seem to be slowly moving toward this system over time.

| Example words with /ɒr/ and /ɔːr/ before a vowel by dialect | ||

|---|---|---|

| Pronounced [ɒɹ] in RP and [ɑɹ~ɒɹ] in eastern coastal American English | Pronounced [ɔːɹ] in RP and eastern coastal American English | |

| Pronounced [ɔɹ] in Canadian English | ||

| Pronounced [ɒɹ~ɑɹ] in General American | Pronounced [ɔɹ] in General American | |

only these four or five words:

|

Words containing /ɒr-/:

|

Words containing /ɔːr-/ or /ɔər-/:

|

Even in the East Coast accents of the United States without the split (Boston, New York City, Rhode Island, Philadelphia, and some coastal Southern), some of the words in the original short-o class often show influence from other American dialects and end up with [-ɔɹ-] anyway. For instance, some speakers from the Northeast pronounce Florida, orange, and horrible with [-ɑɹ-], but foreign and origin with [-ɔɹ-]. Exactly which words are affected by this differs from dialect to dialect and occasionally from speaker to speaker, an example of sound change by lexical diffusion.

Mergers and splits before historic post-vocalic R

/aʊr/–/aʊər/ merger

The Middle English merger of the vowels with the spellings ⟨our⟩ and ⟨ower⟩ (what could be called a flower–flour merger) now affects all modern varieties of English that makes words like sour and hour, which originally had one syllable, have two syllables, and thus flour and flower are homophones. In accents that don't have the merger, flour has one syllable and flower has two syllables. Similar mergers also occur where "hire" gains a syllable rhyming with "flyer" and "coir" gains a syllable rhyming with "employer".[12]

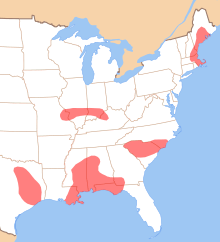

Card–cord merger

The card–cord merger or cord–card merger is a merger of Early Modern English [ɑr] with [ɒr], resulting in homophony of pairs like card/cord, barn/born and far/for. It is roughly similar to the father–bother merger, but before r. The merger is found in some Caribbean English accents, in some versions of the West Country accent in England, and in some accents of Southern American English. [13][14] Areas where the merger occurs include central Texas, Utah, and St. Louis. Dialects with the card–cord merger do not have the horse–hoarse merger. The merger is disappearing in the United States, being replaced by the more common horse–hoarse merger that other regions have.

| /ɑr/ | /ɒr/ | IPA |

|---|---|---|

| arc | orc | ˈɑrk |

| are | or | ˈɑr |

| ark | orc | ˈɑrk |

| barn | born | ˈbɑrn |

| card | chord | ˈkɑrd |

| card | cord | ˈkɑrd |

| dark | dork | ˈdɑrk |

| far | for | ˈfɑr |

| farm | form | ˈfɑrm |

| lard | lord | ˈlɑrd |

| mart | Mort | ˈmɑrt |

| spark | spork | ˈspɑrk |

| stark | stork | ˈstɑrk |

| tar | tor | ˈtɑr |

| tart | tort | ˈtɑrt |

Cure–force merger

In Modern English dialects, the reflexes of Early Modern English /uːr/ and /iur/ are highly susceptible to phonemic merger with other vowels. Words belonging to this class are most commonly spelled with oor, our, ure, or eur; examples include poor, tour, cure, Europe. Wells refers to this class as the cure words, after the keyword of the lexical set to which he assigns them.

In traditional Received Pronunciation and General American, cure words are pronounced with RP /ʊə/ (/ʊər/ before a vowel) and GenAm /ʊr/.[15] But these pronunciations are being replaced by other pronunciations in many English accents.

In southern English English it is now common to pronounce cure words with /ɔː/, so that moor is often pronounced /mɔː/, tour /tɔː/, poor /pɔː/.[16] The traditional form is much more common in the northern counties of England. A similar merger is encountered in many varieties of American English, where the pronunciations [oə] or [or]⁓[ɔr] (depending on whether the accent is rhotic or non-rhotic) prevail.[17][18]

In Australian and New Zealand English the centring diphthong /ʊə/ has practically disappeared, replaced in some words by /ʉː.ə/ (a sequence of two separate monophthongs) and in some by /oː/ (a long monophthong).[19] Which outcome occurs in a particular word is not always predictable, but for example pure, cure and tour come to rhyme with fewer, having /ʉː.ə/, while poor, moor and sure come to rhyme with for and paw, having /oː/.

| /ʊə/ | /ɔː/ | IPA | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| boor | boar | ˈbɔː(r) | With horse–hoarse merger. |

| boor | Boer | ˈbɔː(r) | With horse–hoarse merger. |

| boor | bore | ˈbɔː(r) | With horse–hoarse merger. |

| gourd | gaud | ˈɡɔːd | Non-rhotic. |

| gourd | gored | ˈɡɔː(r)d | With horse–hoarse merger. |

| lure | law | ˈlɔː | Non-rhotic with yod-dropping. |

| lure | lore | ˈlɔː(r) | With horse–hoarse merger and yod-dropping. |

| lured | laud | ˈlɔːd | Non-rhotic with yod-dropping. |

| lured | lawed | ˈlɔːd | Non-rhotic with yod-dropping. |

| lured | lord | ˈlɔː(r)d | With yod-dropping. |

| moor | maw | ˈmɔː | Non-rhotic. |

| moor | more | ˈmɔː(r) | With horse–hoarse merger. |

| poor | paw | ˈpɔː | Non-rhotic. |

| poor | pore | ˈpɔː(r) | With horse–hoarse merger. |

| poor | pour | ˈpɔː(r) | With horse–hoarse merger. |

| sure | shaw | ˈʃɔː | Non-rhotic. |

| sure | shore | ˈʃɔː(r) | With horse–hoarse merger. |

| tour | taw | ˈtɔː | Non-rhotic. |

| tour | tor | ˈtɔː(r) | |

| tour | tore | ˈtɔː(r) | With horse–hoarse merger. |

| toured | toward | ˈtɔːd | Non-rhotic with horse–hoarse merger. |

| whored | hoard | ˈhɔː(r)d | With horse–hoarse merger. whored also has an alternative pronunciation that is already a perfect homophone of hoard. |

| whored | horde | ˈhɔː(r)d | With horse–hoarse merger. whored also has an alternative pronunciation that is already a perfect homophone of horde. |

| your | yaw | ˈjɔː | Non-rhotic. |

| your | yore | ˈjɔː(r) | With horse–hoarse merger. |

| you're | yaw | ˈjɔː | Non-rhotic. |

| you're | yore | ˈjɔː(r) | With horse–hoarse merger. |

Cure–nurse merger

In East Anglia a cure–nurse merger in which words like fury merge to the sound of furry [ɜː] is common, especially after palatal and palatoalveolar consonants, so that sure is often pronounced [ʃɜː] (which is also a common single-word merger in American English, in which the word sure is often /ʃɚ/); yod-dropping may apply as well, yielding pronunciations such as [pɜː] for pure. Other pronunciations in cure–fir merging dialects include /pjɝ/ pure, /ˈk(j)ɝiəs/ curious, /ˈb(j)ɝoʊ/ bureau, /ˈm(j)ɝəl/ mural.[20]

| /jʊə(r)/ | /ɜː(r)/ | IPA | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| cure | cur | ˈkɜː(r) | |

| cure | curr | ˈkɜː(r) | |

| cured | curd | ˈkɜː(r)d | |

| cured | curred | ˈkɜː(r)d | |

| fury | furry | ˈfɜːri | |

| pure | per | ˈpɜː(r) | |

| pure | purr | ˈpɜː(r) |

/aɪər/–/ɑːr/ merger

Varieties of Southern American English, Midland American English, and High Tider English may merge words like fire and far or tired and tarred in the direction of the second words: /ɑːr/. This result in a tire–tar merger, but with tower kept distinct.[21]

/aɪər/–/aʊər/–/ɑːr/ merger

Some accents of southern British English (including many types of RP, as well as the accent of Norwich) have mergers of the vowels in words like tire, tar, and tower. Thus, the triphthong /aʊə/ of tower merges either with the /aɪə/ of tire (both surfacing as diphthongal [ɑə]) or with the /ɑː/ of tar. Some speakers merge all three sounds, so that tower, tire, and tar are all homophonous as [tɑː].[22]

| /aʊə(r)/ | /aɪə(r)/ | /ɑː(r)/ | IPA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bauer | buyer | bar | ˈbɑː(r) |

| coward | - | card | ˈkɑː(r)d |

| cower | - | car | ˈkɑː(r) |

| cowered | - | card | ˈkɑː(r)d |

| - | fire | far | ˈfɑː(r) |

| flour | flyer | - | ˈflɑː(r) |

| flower | flyer | - | ˈflɑː(r) |

| hour | ire | are | ˈɑː(r) |

| Howard | hired | hard | ˈhɑː(r)d |

| - | mire | mar | ˈmɑː(r) |

| our | ire | are | ˈɑː(r) |

| power | pyre | par | ˈpɑː(r) |

| sour | sire | - | ˈsɑː(r) |

| scour | - | scar | ˈskɑː(r) |

| shower | shire | - | ˈʃɑː(r) |

| showered | - | shard | ˈʃɑː(r)d |

| - | spire | spar | ˈspɑː(r) |

| tower | tire | tar | ˈtɑː(r) |

| tower | tyre | tar | ˈtɑː(r) |

Horse–hoarse merger

The horse–hoarse merger or north–force merger is the merger of the vowels /ɔ/ and /o/ before historic /r/, making pairs of words like horse–hoarse, for–four, war–wore, or–oar, morning–mourning etc. homophones. This merger occurs in most varieties of English, which historically has kept the two phonemes separate. In accents that have the merger, horse and hoarse are both pronounced [hɔː(ɹ)s], but in accents that do not have the merger hoarse is pronounced differently, usually [hoɹs] in rhotic and [hoəs] or the like in non-rhotic accents. Non-merging accents include most Scottish, Caribbean, and older Southern American accents, plus some African American vernacular, modern Southern American, Indian, Irish, and older Maine accents.[24][25] Some speakers distinguish the vowels by length rather than quality, pronouncing hoarse [hɔˑɹs] and horse [hɔɹs].[26]

The distinction was made in traditional Received Pronunciation as represented in the first and second editions of the Oxford English Dictionary. The IPA symbols used are /ɔː/ for horse and /ɔə/ for hoarse. In the online version of the Oxford English Dictionary, and in the planned third edition (on-line entries), the pronunciations of horse and hoarse are both given as /hɔːs/.[27]

In the United States, the merger is quite recent in some parts of the country. For example, fieldwork performed in the 1930s by Kurath and McDavid shows the contrast robustly present in the speech of Vermont, northern and western New York State, Virginia, central and southern West Virginia, and North Carolina;[28] but by the 1990s telephone surveys conducted by Labov, Ash, and Boberg show these areas as having almost completely undergone the merger;[29] and even in areas where the distinction is still made, the acoustic difference between the [ɔr] of horse and the [or] of hoarse is rather small for many speakers.[30]

The two groups of words merged by this rule are called the lexical sets north (including horse) and force (including hoarse) by Wells (1982). Etymologically, the north words had /ɒɹ/ and the force words had /oːɹ/.

| Horse class | Hoarse class |

|---|---|

| quarter, war, warm, warn, aura, aural, Thor, born, fortress, important, corpse | board, coarse, hoarse, door, floor, course, pour, oral, more, historian, moron, glory, borne, shorn, sworn, torn, worn, Borneo, afford, force, ford, forge, fort, forth, deport, export, import, porch, pork, port, portend, portent, porter, portion, portrait, proportion, report, sport, support, divorce, sword, corps, hoard, horde |

| /oə/ | /ɔː/ | IPA | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| boar | boor | ˈbɔː(r) | |

| board | baud | ˈbɔːd | non-rhotic |

| board | bawd | ˈbɔːd | non-rhotic |

| boarder | border | ˈbɔː(r)də(r) | |

| Boer | boor | ˈbɔː(r) | |

| bore | boor | ˈbɔː(r) | |

| bored | baud | ˈbɔːd | non-rhotic |

| bored | bawd | ˈbɔːd | non-rhotic |

| borne | bawn | ˈbɔːn | non-rhotic |

| borne | born | ˈbɔː(r)n | |

| Bourne | bawn | ˈbɔːn | non-rhotic |

| Bourne | born | ˈbɔː(r)n | |

| bourse | boss | ˈbɔːs | non-rhotic |

| core | caw | ˈkɔː | non-rhotic |

| cored | cawed | ˈkɔːd | non-rhotic |

| cored | chord | ˈkɔː(r)d | |

| cored | cord | ˈkɔː(r)d | |

| cores | cause | ˈkɔːz | non-rhotic |

| corps | caw | ˈkɔː | non-rhotic |

| court | caught | ˈkɔːt | non-rhotic |

| door | daw | ˈdɔː | non-rhotic |

| floor | flaw | ˈflɔː | non-rhotic |

| fore | for | ˈfɔː(r) | |

| fort | fought | ˈfɔːt | non-rhotic |

| four | for | ˈfɔː(r) | |

| gored | gaud | ˈɡɔːd | non-rhotic |

| hoarse | horse | ˈhɔː(r)s | |

| hoarse | hoss[31] | ˈhɔːs | non-rhotic |

| lore | law | ˈlɔː | non-rhotic |

| more | maw | ˈmɔː | non-rhotic |

| mourning | morning | ˈmɔː(r)nɪŋ | |

| oar | awe | ˈɔː | non-rhotic |

| oar | or | ˈɔː(r) | |

| ore | awe | ˈɔː | non-rhotic |

| ore | or | ˈɔː(r) | |

| pore | paw | ˈpɔː | non-rhotic |

| pores | pause | ˈpɔːz | non-rhotic |

| pour | paw | ˈpɔː | non-rhotic |

| roar | raw | ˈrɔː | non-rhotic |

| shore | shaw | ˈʃɔː | non-rhotic |

| shorn | Sean | ˈʃɔːn | non-rhotic |

| shorn | Shawn | ˈʃɔːn | non-rhotic |

| soar | saw | ˈsɔː | non-rhotic |

| soared | sawed | ˈsɔːd | non-rhotic |

| sore | saw | ˈsɔː | non-rhotic |

| source | sauce | ˈsɔːs | non-rhotic |

| sword | sawed | ˈsɔːd | non-rhotic |

| tore | taw | ˈtɔː | non-rhotic |

| tore | tor | ˈtɔː(r) | |

| wore | war | ˈwɔː(r) | |

| worn | warn | ˈwɔː(r)n | |

| yore | yaw | ˈjɔː | non-rhotic |

Near–square merger

The near–square merger or cheer–chair merger is the merger of the Early Modern English sequences /iːr/ and /ɛːr/ (and the /eːr/ between them), which is found in some accents of modern English. Many speakers in New Zealand[32][33][34] merge them in favor of the NEAR vowel, while some speakers in East Anglia and South Carolina merge them in favor of the SQUARE vowel.[35] The merger is widespread in the Anglophone Caribbean.

| /ɪə(r)/ | /eə(r)/ | IPA (V=ɪ or e) |

|---|---|---|

| beard | Baird | ˈbVə(r)d |

| beer | bare | ˈbVə(r) |

| beer | bear | ˈbVə(r) |

| cheer | chair | ˈtʃVə(r) |

| clear | Claire | ˈklVə(r) |

| dear | dare | ˈdVə(r) |

| deer | dare | ˈdVə(r) |

| ear | air | ˈVə(r) |

| ear | ere | ˈVə(r) |

| ear | heir | ˈVə(r) |

| fear | fair | ˈfVə(r) |

| fear | fare | ˈfVə(r) |

| fleer | flair | ˈflVə(r) |

| fleer | flare | ˈflVə(r) |

| hear | hair | ˈhVə(r) |

| hear | hare | ˈhVə(r) |

| here | hair | ˈhVə(r) |

| here | hare | ˈhVə(r) |

| leer | lair | ˈlVə(r) |

| leered | laird | ˈlVə(r)d |

| mere | mare | ˈmVə(r) |

| near | nare | ˈnVə(r) |

| peer | pair | ˈpVə(r) |

| peer | pare | ˈpVə(r) |

| peer | pear | ˈpVə(r) |

| pier | pair | ˈpVə(r) |

| pier | pare | ˈpVə(r) |

| pier | pear | ˈpVə(r) |

| rear | rare | ˈrVə(r) |

| shear | share | ˈʃVə(r) |

| sheer | share | ˈʃVə(r) |

| sneer | snare | ˈsnVə(r) |

| spear | spare | ˈspVə(r) |

| tear (weep) | tare | ˈtVə(r) |

| tear (weep) | tear (rip) | ˈtVə(r) |

| tier | tare | ˈtVə(r) |

| tier | tear (rip) | ˈtVə(r) |

| weary | wary | ˈwVəri |

| weir | ware | ˈwVə(r) |

| weir | wear | ˈwVə(r) |

| we're | ware | ˈwVə(r) |

| we're | wear | ˈwVə(r) |

Nurse mergers

This is the merger of as many as five Middle English vowels /ɛ, ɪ, ʊ, ɜ, ə/ into one vowel when historically followed by /r/ in the coda of a syllable. The merged vowel is /ɜː/ or /əː/ in Received Pronunciation, and /ɝ/ or /ɚ/ in American and Canadian English. As a result of this merger, the vowels in fir, fern and fur are the same in almost all accents of English; the exceptions are Scottish English and some varieties of Irish English. John C. Wells briefly calls this the NURSE merger.[36] The three separate vowels are retained by some speakers of Scottish English and the term–nurse merger is resisted by some Irish speakers, but the full merger is found in almost all other dialects of English.

- The nurse–fur vowel is also used in:

- The spelling ⟨or⟩ in words like attorney, word, work, world, worm, worse, worship, worst, wort, worth and worthy. Compare the surviving /ʌr/ (barring the Hurry–furry merger) in words like worry.[37]

- The spelling ⟨our⟩ in words like adjourn, courteous, courtesy, journal, journey, scourge and sojourn. Compare the surviving /ʌr/ (barring the Hurry–furry merger) in words like courage, flourish and nourish.[38][39]

- The word were (past tense of to be) uses the term–fern vowel in Scottish English.

- In words like dearth, earl, early, earn, earnest, Earp, earth, heard, hearse, Hearst, learn, learnt, pearl, rehearse, search and yearn:

- In Scottish English, these use the term–fern vowel. This makes heard and herd rhyme.

| /ɛr/ | */er/ | /ɪr/ | /ʌr/ | IPA | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bern | - | - | burn | ˈbɜː(r)n | |

| Bert | - | - | Burt | ˈbɜː(r)t | |

| berth | - | birth | - | ˈbɜː(r)θ | |

| - | earn | - | urn | ˈɜː(r)n | |

| Ernest | earnest | - | - | ˈɜː(r)nɪst | |

| herd | heard | - | - | ˈhɜː(r)d | |

| herl | - | - | hurl | ˈhɜː(r)l | |

| - | Hearst | - | hurst | ˈhɜː(r)st | |

| - | - | fir | fur | ˈfɜː(r) | |

| kerb | - | - | curb | ˈkɜː(r)b | |

| mer- | - | myrrh | murr | ˈmɜː(r) | |

| - | - | mirk | murk | ˈmɜː(r)k | |

| Perl | pearl | - | - | ˈpɜː(r)l | |

| tern | - | - | turn | ˈtɜː(r)n | |

| - | - | whirl | whorl | ˈwɜː(r)l | |

| - | - | whirled | world | ˈwɜː(r)ld | With wine–whine merger. |

Nurse–near merger

In older varieties of Southern American English and the West Country dialects of English English, words like beard is pronounced very close to bird, though more precisely as /bjɝd/,[40] meaning that there is no complete merger: word pairs like beer and burr are still distinguished as /bjɝ/ vs. /bɝ/. However, if the syllable begins with a consonant cluster (e.g. queer) or a palato-alveolar consonant (e.g. cheer), then there is no /j/ sound: /kwɝ/, /tʃɝ/. It is thus possible that pairs like steer-stir are merged in some accents as /stɝ/, although this is not explicitly reported in the literature.

There is evidence that African American Vernacular English speakers in Memphis, Tennessee, merge both /ɪr/ and /ɛər/ with /ɝ/, so that here and hair are both homophonous with the strong pronunciation of her.[41]

Nurse–north merger

The nurse–north merger (of words like perk towards the sound of pork) involves English vowels /ɜr/ and /ɔr/ into [ɔː] that occurs in broadest Geordie.[42]

Square–nurse merger

The square–nurse merger or fur–fair merger is a merger of /ɜː(r)/ with /eə(r)/ that occurs in some accents (for example Liverpool, new Dublin, and Belfast).[43] The phonemes are merged to [ɛ:] in Hull and Middlesbrough.[44][45][46]

Shorrocks reports that, in the dialect of Bolton, the two sets are generally merged to /ɵ:/, but some NURSE words such as first have a short /ɵ/.[47]

This merger is found in some varieties of African American Vernacular English to the sound IPA: [ɜɹ]: "A recent development reported for some AAE (in Memphis, but likely found elsewhere)".[48] This is exemplified in Chingy's song "Right Thurr"; the merger is heard at the beginning of the song, but he goes on to use standard pronunciation for the rest of the song.

Labov (1994) also reports such a merger in some western parts of the United States "with a high degree of r constriction".

| /eə(r)/ | /ɜː(r)/ | IPA | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| air | err | ˈɜː(r) | |

| Baird | bird | ˈbɜː(r)d | |

| Baird | burd | ˈbɜː(r)d | |

| Baird | burred | ˈbɜː(r)d | |

| bare | burr | ˈbɜː(r) | |

| bared | bird | ˈbɜː(r)d | |

| bared | burd | ˈbɜː(r)d | |

| bared | burred | ˈbɜː(r)d | |

| bear | burr | ˈbɜː(r) | |

| Blair | blur | ˈblɜː(r) | |

| blare | blur | ˈblɜː(r) | |

| cairn | kern | ˈkɜː(r)n | |

| care | cur | ˈkɜː(r) | |

| care | curr | ˈkɜː(r) | |

| cared | curd | ˈkɜː(r)d | |

| cared | curred | ˈkɜː(r)d | |

| cared | Kurd | ˈkɜː(r)d | |

| chair | chirr | ˈtʃɜː(r) | |

| ere | err | ˈɜː(r) | |

| fair | fir | ˈfɜː(r) | |

| fair | fur | ˈfɜː(r) | |

| fare | fir | ˈfɜː(r) | |

| fare | fur | ˈfɜː(r) | |

| hair | her | ˈhɜː(r) | |

| haired | heard | ˈhɜː(r)d | |

| haired | herd | ˈhɜː(r)d | |

| hare | her | ˈhɜː(r) | |

| heir | err | ˈɜː(r) | |

| pair | per | ˈpɜː(r) | |

| pair | purr | ˈpɜː(r) | |

| pare | per | ˈpɜː(r) | |

| pare | purr | ˈpɜː(r) | |

| pear | per | ˈpɜː(r) | |

| pear | purr | ˈpɜː(r) | |

| share | sure | ˈʃɜː(r) | with cure–fir merger |

| spare | spur | ˈspɜː(r) | |

| stair | stir | ˈstɜː(r) | |

| stare | stir | ˈstɜː(r) | |

| ware | whir | ˈwɜː(r) | with wine–whine merger |

| ware | were | ˈwɜː(r) | |

| wear | whir | ˈwɜː(r) | with wine–whine merger |

| wear | were | ˈwɜː(r) | |

| where | were | ˈwɜː(r) | with wine–whine merger |

| where | whir | ˈhwɜː(r) |

See also

- Phonological history of English

- Phonological history of English vowels

- Coil–curl merger

- English phonology

- History of English

- R-colored vowel

Sound samples

- ↑ http://www.alt-usage-english.org/mmm_bc.wav Sample of a speaker with the Mary–marry–merry merger Text: "Mary, dear, make me merry; say you'll marry me."

- ↑ http://www.alt-usage-english.org/mmm_rf.wav Sample of a speaker with the three-way distinction

References

- ↑ Wells 1982c, pp. 479–485.

- ↑ Wells 1982a, pp. 201–2, 244.

- ↑ "Dialect Survey Question 15: How do you pronounce Mary/merry/marry?". Archived from the original on November 25, 2006.

- ↑ Wells 1982c, pp. 480-82.

- 1 2 3 4 Dialect Survey.

- ↑ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006), pp. 56

- ↑ Labov, Ash & Boberg 2006, pp. 54, 56.

- ↑ Wells 1982c, p. 485.

- ↑ Labov, Ash & Boberg 2006, pp. 54, 238.

- ↑ Labov, William (2006). The Social Stratification of English in New York City (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 29.

- ↑ Shitara 1993.

- ↑ "Guide to Pronunciation" (PDF). Merriam-Webster. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 21, 2015.

- ↑ Labov, Ash & Boberg 2006, pp. 51–53.

- ↑ Wells 1982a, pp. 158, 160, 347, 483, 548, 576–77, 582, 587.

- ↑ "Cure (AmE)". Merriam-Webster."Cure (AmE)". Dictionary.com.

- ↑ Wells 1982a, pp. 56, 65–66, 164, 237, 287–88.

- ↑ Kenyon 1951, pp. 233–34.

- ↑ Wells 1982c, p. 549.

- ↑ "Distinctive Features: Australian English". Macquarie University. Archived from the original on March 29, 2008. See also Macquarie University Dictionary and other dictionaries of Australian English.

- ↑ Hammond 1999, p. 52.

- ↑ Kurath & McDavid 1961, p. 122.

- ↑ Wells 1982b, pp. 238–42, 286, 292–93, 339.

- ↑ Labov, Ash & Boberg 2006, p. 52.

- ↑ "Chapter 8: Nearly completed mergers". Macquarie University. Archived from the original on July 19, 2006.

- ↑ Wells 1982a, pp. 159–61, 234–36, 287, 408, 421, 483, 549–50, 557, 579, 626.

- ↑ Wells 1982c, p. 483.

- ↑ OED entries for horse and hoarse

- ↑ Kurath & McDavid 1961, map 44

- ↑ Labov, Ash & Boberg 2006, map 8.2

- ↑ Labov, Ash & Boberg 2006, p. 51.

- ↑ hoss, Dictionary.com

- ↑ Bauer et al. 2007, p. 98.

- ↑ Bauer & Warren 2004, p. 592.

- ↑ Hay, Maclagan & Gordon 2008, pp. 39–41.

- ↑ Wells 1982b, pp. 338, 512, 547, 557, 608.

- ↑ Wells 1982a, p. 200.

- ↑ Oxford English Dictionary entry at worry

- ↑ Oxford English Dictionary entries

- ↑ AHD 2nd edition, 1392

- ↑ Kurath & McDavid 1961, pp. 117–18 and maps 33–36.

- ↑ "Child Phonology Laboratory". Archived from the original on April 15, 2005.

- ↑ Wells (1982b:374)

- ↑ Wells 1982c, pp. 372, 421, 444.

- ↑ Handbook of Varieties of English, page 125, Walter de Gruyter, 2004

- ↑ Williams and Kerswill in Urban Voices, Arnold, London, 1999, page 146

- ↑ Williams and Kerswill in Urban Voices, Arnold, London, 1999, page 143

- ↑ Shorrocks, Graham (1998). A Grammar of the Dialect of the Bolton Area. Pt. 1: Phonology. Bamberger Beiträge zur englischen Sprachwissenschaft; Bd. 41. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang. ISBN 3-631-33066-9.

- ↑ Thomas, Erik (2007). "Phonological and Phonetic Characteristics of African American Vernacular English". Language and Linguistics Compass 1/5. North Carolina State University. p. 466.

Bibliography

- Bauer, Laurie; Warren, Paul (2004), "New Zealand English: phonology", in Schneider, Edgar W.; Burridge, Kate; Kortmann, Bernd; Mesthrie, Rajend; Upton, Clive, A handbook of varieties of English, 1: Phonology, Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 580–602, ISBN 3-11-017532-0

- Bauer, Laurie; Warren, Paul; Bardsley, Dianne; Kennedy, Marianna; Major, George (2007), "New Zealand English", Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 37 (1): 97–102, doi:10.1017/S0025100306002830

- Hammond, Michael (1999), The Phonology of English, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-823797-9

- Hay, Jennifer; Maclagan, Margaret; Gordon, Elizabeth (2008), "2. Phonetics and Phonology", New Zealand English, Dialects of English, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, ISBN 978-0-7486-2529-1

- Kenyon, John S. (1951), American Pronunciation (10th ed.), Ann Arbor, Michigan: George Wahr Publishing Company, ISBN 1-884739-08-3

- Kurath, Hans; McDavid, Raven I. (1961), The Pronunciation of English in the Atlantic States, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, ISBN 0-8173-0129-1

- Labov, William; Ash, Sharon; Boberg, Charles (2006), The Atlas of North American English, Berlin: Mouton-de Gruyter, pp. 187–208, ISBN 3-11-016746-8

- Shitara, Yuko (1993), "A survey of American pronunciation preferences", Speech Hearing and Language, 7: 201–232

- Wells, John C. (1982a), Accents of English I: An Introduction, Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-29719-2

- Wells, John C. (1982b), Accents of English 2: The British Isles, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-24224-X

- Wells, John C. (1982c), Accents of English 3: Beyond the British Isles, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-28541-0