Hormone

A hormone (from the Greek participle “ὁρμῶν”) is any member of a class of signaling molecules produced by glands in multicellular organisms that are transported by the circulatory system to target distant organs to regulate physiology and behaviour. Hormones have diverse chemical structures, mainly of 3 classes: eicosanoids, steroids, and amino acid/protein derivatives (amines, peptides, and proteins). The glands that secrete hormones comprise the endocrine signaling system. The term hormone is sometimes extended to include chemicals produced by cells that affect the same cell (autocrine or intracrine signalling) or nearby cells (paracrine signalling).

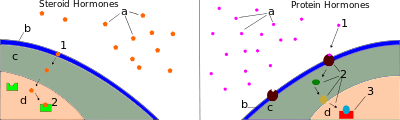

Hormones are used to communicate between organs and tissues for physiological regulation and behavioral activities, such as digestion, metabolism, respiration, tissue function, sensory perception, sleep, excretion, lactation, stress, growth and development, movement, reproduction, and mood.[1][2] Hormones affect distant cells by binding to specific receptor proteins in the target cell resulting in a change in cell function. When a hormone binds to the receptor, it results in the activation of a signal transduction pathway. This may lead to cell type-specific responses that include rapid non-genomic effects or slower genomic responses where the hormones acting through their receptors activate gene transcription resulting in increased expression of target proteins. Amino acid–based hormones (amines and peptide or protein hormones) are water-soluble and act on the surface of target cells via second messengers; steroid hormones, being lipid-soluble, move through the plasma membranes of target cells (both cytoplasmic and nuclear) to act within their nuclei.

Hormone secretion may occur in many tissues. Endocrine glands are the cardinal example, but specialized cells in various other organs also secrete hormones. Hormone secretion occurs in response to specific biochemical signals from a wide range of regulatory systems. For instance, serum calcium concentration affects parathyroid hormone synthesis; blood sugar (serum glucose concentration) affects insulin synthesis; and because the outputs of the stomach and exocrine pancreas (the amounts of gastric juice and pancreatic juice) become the input of the small intestine, the small intestine secretes hormones to stimulate or inhibit the stomach and pancreas based on how busy it is. Regulation of hormone synthesis of gonadal hormones, adrenocortical hormones, and thyroid hormones is often dependent on complex sets of direct influence and feedback interactions involving the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA), -gonadal (HPG), and -thyroid (HPT) axes.

Upon secretion, certain hormones, including protein hormones and catecholamines, are water-soluble and are thus readily transported through the circulatory system. Other hormones, including steroid and thyroid hormones, are lipid-soluble; to allow for their widespread distribution, these hormones must bond to carrier plasma glycoproteins (e.g., thyroxine-binding globulin (TBG)) to form ligand-protein complexes. Some hormones are completely active when released into the bloodstream (as is the case for insulin and growth hormones), while others are prohormones that must be activated in specific cells through a series of activation steps that are commonly highly regulated. The endocrine system secretes hormones directly into the bloodstream typically into fenestrated capillaries, whereas the exocrine system secretes its hormones indirectly using ducts. Hormones with paracrine function diffuse through the interstitial spaces to nearby target tissue.

Overview

Hormonal signaling involves the following steps:[3]

- Biosynthesis of a particular hormone in a particular tissue

- Storage and secretion of the hormone

- Transport of the hormone to the target cell(s)

- Recognition of the hormone by an associated cell membrane or intracellular receptor protein

- Relay and amplification of the received hormonal signal via a signal transduction process: This then leads to a cellular response. The reaction of the target cells may then be recognized by the original hormone-producing cells, leading to a down-regulation in hormone production. This is an example of a homeostatic negative feedback loop.

- Breakdown of the hormone.

Hormone cells are typically of a specialized cell type, residing within a particular endocrine gland, such as the thyroid gland, ovaries, and testes. Hormones exit their cell of origin via exocytosis or another means of membrane transport. The hierarchical model is an oversimplification of the hormonal signaling process. Cellular recipients of a particular hormonal signal may be one of several cell types that reside within a number of different tissues, as is the case for insulin, which triggers a diverse range of systemic physiological effects. Different tissue types may also respond differently to the same hormonal signal.

Regulation

The rate of hormone biosynthesis and secretion is often regulated by a homeostatic negative feedback control mechanism. Such a mechanism depends on factors that influence the metabolism and excretion of hormones. Thus, higher hormone concentration alone cannot trigger the negative feedback mechanism. Negative feedback must be triggered by overproduction of an "effect" of the hormone.

Hormone secretion can be stimulated and inhibited by:

- Other hormones (stimulating- or releasing -hormones)

- Plasma concentrations of ions or nutrients, as well as binding globulins

- Neurons and mental activity

- Environmental changes, e.g., of light or temperature

One special group of hormones is the tropic hormones that stimulate the hormone production of other endocrine glands. For example, thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) causes growth and increased activity of another endocrine gland, the thyroid, which increases output of thyroid hormones.

To release active hormones quickly into the circulation, hormone biosynthetic cells may produce and store biologically inactive hormones in the form of pre- or prohormones. These can then be quickly converted into their active hormone form in response to a particular stimulus.

Eicosanoids are considered to act as local hormones. They are considered to be "local" because they possess specific effects on target cells close to their site of formation. They also have a rapid degradation cycle, making sure they do not reach distal sites within the body.[4]

Receptors

Most hormones initiate a cellular response by initially binding to either cell membrane associated or intracellular receptors. A cell may have several different receptor types that recognize the same hormone but activate different signal transduction pathways, or a cell may have several different receptors that recognize different hormones and activate the same biochemical pathway.

Receptors for most peptide as well as many eicosanoid hormones are embedded in the plasma membrane at the surface of the cell and the majority of these receptors belong to the G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) class of seven alpha helix transmembrane proteins. The interaction of hormone and receptor typically triggers a cascade of secondary effects within the cytoplasm of the cell, often involving phosphorylation or dephosphorylation of various other cytoplasmic proteins, changes in ion channel permeability, or increased concentrations of intracellular molecules that may act as secondary messengers (e.g., cyclic AMP). Some protein hormones also interact with intracellular receptors located in the cytoplasm or nucleus by an intracrine mechanism.

For steroid or thyroid hormones, their receptors are located inside the cell within the cytoplasm of the target cell. These receptors belong to the nuclear receptor family of ligand-activated transcription factors. To bind their receptors, these hormones must first cross the cell membrane. They can do so because they are lipid-soluble. The combined hormone-receptor complex then moves across the nuclear membrane into the nucleus of the cell, where it binds to specific DNA sequences, regulating the expression of certain genes, and thereby increasing the levels of the proteins encoded by these genes.[5] However, it has been shown that not all steroid receptors are located inside the cell. Some are associated with the plasma membrane.[6]

Effects

Hormones have the following effects on the body:

- stimulation or inhibition of growth

- wake-sleep cycle and other circadian rhythms

- mood swings

- induction or suppression of apoptosis (programmed cell death)

- activation or inhibition of the immune system

- regulation of metabolism

- preparation of the body for mating, fighting, fleeing, and other activity

- preparation of the body for a new phase of life, such as puberty, parenting, and menopause

- control of the reproductive cycle

- hunger cravings

- sexual arousal

A hormone may also regulate the production and release of other hormones. Hormone signals control the internal environment of the body through homeostasis.

Chemical classes

As hormones are defined functionally, not structurally, they may have diverse chemical structures. Hormones occur in multicellular organisms (plants, animals, fungi, brown algae and red algae). These compounds occur also in unicellular organisms, and may act as signaling molecules,[7][8] but there is no consensus if, in this case, they can be called hormones.

Animal

Vertebrate hormones fall into three main chemical classes:

- Amino acid derived – Examples include melatonin and thyroxine.

- Peptides, polypeptides and proteins. – Small peptide hormones include TRH and vasopressin. Peptides composed of scores or hundreds of amino acids are referred to as proteins. Examples of protein hormones include insulin and growth hormone. More complex protein hormones bear carbohydrate side-chains and are called glycoprotein hormones. Luteinizing hormone, follicle-stimulating hormone and thyroid-stimulating hormone are examples of glycoprotein hormones.

- Eicosanoids – hormones derive from lipids such as arachidonic acid, lipoxins and prostaglandins. These hormones are produced by cyclooxygenases and lipoxygenases and there are many drugs that include the NSAIDs like ibuprofen and naproxen which effect the activity of the cyclooxygenases and inhibit the formation of these eicosanoid hormones.[9]

- Steroid – Hormones dervied from cholesterol. Examples of steroid hormones include the sex hormones estradiol and testosterone as well as the stress hormone cortisol.[10]

Compared with vertebrates, insects and crustaceans possess a number of structurally unusual hormones such as the juvenile hormone, a sesquiterpenoid.[11]

Plant

Plant hormones include abscisic acid, auxin, cytokinin, ethylene, and gibberellin.

Therapeutic use

Many hormones and their structural and functional analogs are used as medication. The most commonly prescribed hormones are estrogens and progestogens (as methods of hormonal contraception and as HRT),[12] thyroxine (as levothyroxine, for hypothyroidism) and steroids (for autoimmune diseases and several respiratory disorders). Insulin is used by many diabetics. Local preparations for use in otolaryngology often contain pharmacologic equivalents of adrenaline, while steroid and vitamin D creams are used extensively in dermatological practice.

A "pharmacologic dose" or "supraphysiological dose" of a hormone is a medical usage referring to an amount of a hormone far greater than naturally occurs in a healthy body. The effects of pharmacologic doses of hormones may be different from responses to naturally occurring amounts and may be therapeutically useful, though not without potentially adverse side effects. An example is the ability of pharmacologic doses of glucocorticoids to suppress inflammation.

Hormone-behavior interactions

At the neurological level, behavior can be inferred based on: hormone concentrations; hormone-release patterns; the numbers and locations of hormone receptors; and the efficiency of hormone receptors for those involved in gene transcription. Not only do hormones influence behavior, but also behavior and the environment influence hormones. Thus, a feedback loop is formed. For example, behavior can affect hormones, which in turn can affect behavior, which in turn can affect hormones, and so on.

Three broad stages of reasoning may be used when determining hormone-behavior interactions:

- The frequency of occurrence of a hormonally dependent behavior should correspond to that of its hormonal source

- A hormonally dependent behavior is not expected if the hormonal source (or its types of action) is non-existent

- The reintroduction of a missing behaviorally dependent hormonal source (or its types of action) is expected to bring back the absent behavior

Comparison with neurotransmitters

There are various clear distinctions between hormones and neurotransmitters:

- A hormone can perform functions over a larger spatial and temporal scale than can a neurotransmitter.

- Hormonal signals can travel virtually anywhere in the circulatory system, whereas neural signals are restricted to pre-existing nerve tracts

- Assuming the travel distance is equivalent, neural signals can be transmitted much more quickly (in the range of milliseconds) than can hormonal signals (in the range of seconds, minutes, or hours). Neural signals can be sent at speeds up to 100 meters per second.

- Neural signalling is an all-or-nothing (digital) action, whereas hormonal signalling is an action that can be continuously variable as dependent upon hormone concentration.

Binding Proteins

Hormone transport and the involvement of binding proteins is an essential aspect when considering the function of hormones. There are several benefits with the formation of a complex with a binding protein: the effective half-life of the bound hormone is increased; a reservoir of bound hormones is created, which evens the variations in concentration of unbound hormones (bound hormones will replace the unbound hormones when these are eliminated).[13]

Discovery

The discovery of hormones and endocrine signaling occurred during studies of how the digestive system regulates its activities, as explained at Secretin § Discovery.

See also

- Autocrine signaling

- Cytokine

- Endocrine system

- Endocrinology

- Environmental hormones

- Growth factor

- Hormone disruptor

- Intracrine

- List of investigational hormonal agents

- Metabolomics

- Neuroendocrinology

- Paracrine signaling

- Plant hormones or plant growth regulators

- Semiochemical

- Sexual motivation and hormones

References

- ↑ Neave N (2008). Hormones and behaviour: a psychological approach. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press. ISBN 978-0521692014. Lay summary – Project Muse.

- ↑ "Hormones". MedlinePlus. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ↑ Nussey S, Whitehead S (2001). Endocrinology: an integrated approach. Oxford: Bios Scientific Publ. ISBN 978-1-85996-252-7.

- ↑ "Eicosanoids". www.rpi.edu. Retrieved 2017-02-08.

- ↑ Beato M, Chavez S, Truss M (1996). "Transcriptional regulation by steroid hormones". Steroids. 61 (4): 240–251. PMID 8733009. doi:10.1016/0039-128X(96)00030-X.

- ↑ Hammes SR (2003). "The further redefining of steroid-mediated signaling". Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 100 (5): 21680–2170. PMC 151311

. PMID 12606724. doi:10.1073/pnas.0530224100.

. PMID 12606724. doi:10.1073/pnas.0530224100. - ↑ Lenard J (1992). "Mammalian hormones in microbial cells". Trends Biochem. Sci. 17 (4): 147–50. PMID 1585458. doi:10.1016/0968-0004(92)90323-2.

- ↑ Janssens PM. "Did vertebrate signal transduction mechanisms originate in eukaryotic microbes?". Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 12: 456–459. doi:10.1016/0968-0004(87)90223-4.

- ↑ "Eicosanoid Synthesis and Metabolism: Prostaglandins, Thromboxanes, Leukotrienes, Lipoxins". themedicalbiochemistrypage.org. Retrieved 2017-02-07.

- ↑ Marieb, Elaine (2014). Anatomy & physiology. Glenview, IL: Pearson Education, Inc. ISBN 978-0321861580.

- ↑ Heyland A, Hodin J, Reitzel AM (2005). "Hormone signaling in evolution and development: a non-model system approach". BioEssays. 27 (1): 64–75. PMID 15612033. doi:10.1002/bies.20136.

- ↑ "Hormone Therapy". Cleveland Clinic.

- ↑ Boron WF, Boulpaep EL. Medical physiology : a cellular and molecular approach. Updated 2. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders Elsevier; 2012.

External links

- The Hormone Foundation

- Article on hormones and their receptors

- HMRbase: A database of hormones and their receptors

- Hormones at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)