S-75 Dvina

| S-75 Lea / V-750 SA-2 Guideline | |

|---|---|

|

S-75 including V-750 missile on camouflaged launcher | |

| Type | Strategic SAM system |

| Place of origin | Soviet Union |

| Service history | |

| In service | 1957–present |

| Used by | See list of present and former operators |

| Wars | Vietnam War, Six-Day War, Indo-Pakistani War of 1965, Indo-Pakistani War of 1971, Yom Kippur War, Cold War, Iran–Iraq War, Gulf War, War in Abkhazia (1992–93), First Libyan Civil War, Syrian Civil War, Yemeni Civil War (2015-present), Saudi-led intervention in Yemen (2015-present), Conflict in Najran, Jizan and Asir |

| Production history | |

| Designer |

Raspletin KB-1 (head developer), |

| Designed | 1953–1957 |

| Produced | 1957 |

| No. built | Approx 4,600 launchers produced[1] |

| Variants | S-75 Dvina, S-75M-2 Volkhov-M, S-75 Desna, S-75M Volkhov, S-75M Volga |

| Specifications (V-750[2]) | |

| Weight | 2,300 kg (5,100 lb) |

| Length | 10,600 mm (420 in) |

| Diameter | 700 mm (28 in) |

| Warhead | Frag-HE |

| Warhead weight | 200 kg (440 lb) |

Detonation mechanism | Command |

|

| |

| Propellant | Solid-fuel booster and a storable liquid-fuel upper stage |

Operational range | 45 km (28 mi) |

| Flight altitude | 25,000 m (82,000 ft) |

| Boost time | 5 s boost, then 20 s sustain |

| Speed | Mach 3.5 |

Guidance system | Radio control command guidance |

| Accuracy | 65 m |

Launch platform | Single rail, ground mounted (not mobile) |

The S-75 Dvina (Russian: С-75; NATO reporting name SA-2 Guideline) is a Soviet-designed, high-altitude air defence system, built around a surface-to-air missile with command guidance. Since its first deployment in 1957 it has become the most widely deployed air defence system in history. It scored the first destruction of an enemy aircraft by a surface-to-air missile, shooting down a Taiwanese Martin RB-57D Canberra over China, on 7 October 1959, hitting it with three V-750 (1D) missiles at an altitude of 20 km (65,600 ft). This success was attributed to Chinese fighter aircraft at the time in order to keep the S-75 program secret.[3]

This system first gained international fame when an S-75 battery, using the newer, longer-range and higher-altitude V-750VN (13D) missile was deployed in the 1960 U-2 incident, when it shot down the U-2 of Francis Gary Powers overflying the Soviet Union on May 1, 1960.[4] The system was also deployed in Cuba during the Cuban Missile Crisis, when it shot down another U-2 (piloted by Rudolf Anderson) overflying Cuba on October 27, 1962, almost precipitating a nuclear war.[5] North Vietnamese forces used the S-75 extensively during the Vietnam War to defend Hanoi and Haiphong. It has also been locally produced in the People's Republic of China using the names HQ-1 and HQ-2.[6]

History

Development

In the early 1950s, the United States Air Force rapidly accelerated its development of long-range jet bombers carrying nuclear weapons. The USAF program led to the deployment of Boeing B-47 Stratojet supported by aerial refueling aircraft to extend its range deep into the Soviet Union. The USAF quickly followed the B-47 with the development of the Boeing B-52 Stratofortress, which had greater range and payload than the B-47. The range, speed, and payload of these U.S. bombers posed a significant threat to the Soviet Union in the event of a war between the two countries.

Consequently, the Soviets initiated the development of improved air defence systems. Although the Soviet Air Defence Forces had large numbers of anti-aircraft artillery (AAA), including radar-directed batteries, the limitations of guns versus high-altitude jet bombers were obvious. Therefore, the Soviet Air Defence Forces began the development of missile systems to replace the World War II-vintage gun defences.

In 1953, KB-2 began the development of what became the S-75 under the direction of Pyotr Grushin. This program focused on producing a missile which could bring down a large, non-maneuvering, high-altitude aircraft. As such it did not need to be highly maneuverable, merely fast and able to resist aircraft counter-measures. For such a pioneering system, development proceeded rapidly, and testing began a few years later. In 1957, the wider public first became aware of the S-75 when the missile was shown at that year's May Day parade in Moscow.

Initial deployment

Wide-scale deployment started in 1957, with various upgrades following over the next few years. The S-75 was never meant to replace the S-25 Berkut surface-to-air missile sites around Moscow, but it did replace high-altitude anti-aircraft guns, such as the 130 mm KS-30 and 100 mm KS-19. Between mid-1958 and 1964, U.S. intelligence assets located more than 600 S-75 sites in the USSR. These sites tended to cluster around population centers, industrial complexes, and government control centers. A ring of sites was also located around likely bomber routes into the Soviet heartland. By the mid-1960s, the Soviet Union had ended the deployment of the S-75 with perhaps 1,000 operational sites.

In addition to the Soviet Union, several S-75 batteries were deployed during the 1960s in East Germany to protect Soviet forces stationed in that country. Later the system was sold to most Warsaw Pact countries and was provided to China, North Korea, and eventually, North Vietnam.[6]

Employment

While the shooting down of Francis Gary Powers' U-2 in 1960 is the first publicized success for the S-75, the first aircraft shot down by the S-75 was a Taiwanese Martin RB-57D Canberra high-altitude reconnaissance aircraft. The aircraft was hit by a Chinese-operated S-75 site near Beijing on October 7, 1959.[3] Over the next few years, the Taiwanese ROCAF would lose several aircraft to the S-75: both RB-57s and various drones. On May 1, 1960, Gary Powers' U-2 was shot down while flying over the testing site near Sverdlovsk. The first missile destroyed the U-2, and a further 13 were also fired, hitting a pursuing high-altitude MiG-19. That action led to the U-2 Crisis of 1960. Additionally, Chinese S-75s downed five ROCAF-piloted U-2s based in Taiwan.[7]

During the Cuban Missile Crisis, a U-2 piloted by USAF Major Rudolf Anderson was shot down over Cuba by an S-75 in October 1962.[8]

In 1965, North Vietnam asked for some assistance against American airpower, for their own air-defence system lacked the ability to shoot down aircraft flying at high altitude. After some discussion it was agreed to supply the PAVN with the S-75. The decision was not made lightly, because it greatly increased the chances that one would fall into US hands for study. Site preparation started early in the year, and the US detected the program almost immediately on 5 April 1965.

.jpg)

On 24 July 1965, a USAF F-4C aircraft was shot down by an SA-2.[9] Three days later, the US responded with Operation Iron Hand to attack the other sites before they could become operational. Most of the S-75 were deployed around the Hanoi-Haiphong area and were off-limits to attack (as were local airfields) for political reasons.

The missile system was used widely throughout the world, especially in the Middle East, where Egypt and Syria used them to defend against the Israeli Air Force, with the air defence net accounting for the majority of the downed Israeli aircraft. The last success seems to have occurred during the War in Abkhazia (1992–1993), when Georgian missiles shot down a Russian Sukhoi Su-27 fighter near Gudauta on March 19, 1993.[10]

During the Yemeni Civil War (2015-present) Houthis modified some of their S-75 into surface-to-surface ballistic missiles to attack Saudi bases with them.[11][12]

Countermeasures and counter-countermeasures

Between 1965 and 1966, the US delivered countermeasures to the S-75 problem. The Navy soon had the AGM-45 Shrike in service and mounted their first offensive strike on a site in October 1965. The Air Force fitted B-66 bombers with powerful jammers (which blinded the early warning radars) and by developing smaller jamming pods for fighters (which denied range information to the radars). Later developments included the Wild Weasel aircraft, which were fitted with anti-radiation air-to-surface missile systems made to home in on the radar from the threat. This freed them to shoot the sites with Shrikes of their own.

The Soviets and Vietnamese were able to adapt to some of these tactics. The USSR upgraded the radar several times to improve ECM (electronic counter measures) resistance. They also introduced a passive guidance mode, whereby the tracking radar could lock on the jamming signal itself and guide missiles directly towards the jamming source. This also meant the SAM site's tracking radar could be turned off, which prevented Shrikes from homing in on it. Some new tactics were developed to combat the Shrike. One of them was to point the radar to the side and then turn it off briefly. Since the Shrike was a relatively primitive anti-radiation missile, it would follow the beam away from the radar and then simply crash when it lost the signal (after the radar was turned off). SAM crews could briefly illuminate a hostile aircraft to see if the target was equipped with a Shrike. If the aircraft fired one, the Shrike could be neutralized with the side-pointing technique without sacrificing any S-75s. Another tactic was a "false launch" in which missile guidance signals were transmitted without a missile being launched. This could distract enemy pilots, or even occasionally cause them to drop ordnance prematurely to lighten their aircraft enough to dodge the nonexistent missile.

Despite these advances, the US was able to come up with effective ECM packages for the B-52E and later models. When the B-52s flew large-scale raids against Hanoi and Haiphong over an eleven-day period in December 1972, 266 S-75 missiles were fired,[13] resulting in the loss of 15 of the bombers and damage to numerous others. The ECM proved to be generally effective, but repetitive USAF flight tactics early in the bombing campaign had increased the vulnerability of the bombers, and the North Vietnamese missile crews adopted a practice of firing large S-75 salvos to overwhelm the planes' defensive countermeasures (see Operation Linebacker II). By the conclusion of the Linebacker II campaign, the shootdown rate of the S-75 against the B-52s was 2% (15 losses for 729 flown sorties).

Replacement systems

Soviet Air Defence Forces started to replace the S-75 with the vastly superior S-300 system in the 1980s. The S-75 remains in widespread service throughout the world, with some level of operational ability in 35 countries. Vietnam and Egypt are tied for the largest deployments at 280 missiles each, while North Korea has 270, and Poland has 240. The Chinese also deploy the HQ-2, an upgrade of the S-75, in relatively large numbers.

Description

Soviet doctrinal organization

The Soviet Union used a fairly standard organizational structure for S-75 units. Other countries that have employed the S-75 may have modified this structure. Typically, the S-75 is organized into a regimental structure with three subordinate battalions. The regimental headquarters will control the early-warning radars and coordinate battalion actions. The battalions will contain several batteries with their associated acquisition and targeting radars.

Site layout

Each battalion will typically have six, semi-fixed, single-rail launchers for their V-750 missiles positioned approximately 60 to 100 m (200 to 330 ft) apart from each other in a hexagonal "flower" pattern, with radars and guidance systems placed in the center. It was this unique "flower" shape that led to the sites being easily recognizable in reconnaissance photos. Typically another six missiles are stored on tractor-trailers near the center of the site.

Missile

The V-750 is a two-stage missile consisting of a solid-fuel booster and a storable liquid-fuel upper stage, which burns red fuming nitric acid as the oxidizer and kerosene as the fuel. The booster fires for about 4–5 seconds and the main engine for about 22 seconds, by which time the missile is traveling at about Mach 3. The booster mounts four large, cropped-delta wing fins that have small control surfaces in their trailing edges to control roll. The upper stage has smaller cropped-deltas near the middle of the airframe, with a smaller set of control surfaces at the extreme rear and (in most models) much smaller fins on the nose.

The missiles are guided using radio control signals (sent on one of three channels) from the guidance computers at the site. The earlier S-75 models received their commands via two sets of four small antennas in front of the forward fins while the D model and later models used four much larger strip antennas running between the forward and middle fins. The guidance system at an S-75 site can handle only one target at a time, but it can direct three missiles against it. Additional missiles could be fired against the same target after one or more missiles of the first salvo had completed their run, freeing the radio channel.

The missile typically mounts a 195 kg (430 lb) fragmentation warhead, with proximity, contact, and command fusing. The warhead has a lethal radius of about 65 m (213 ft) at lower altitudes, but at higher altitudes the thinner atmosphere allows for a wider radius of up to 250 m (820 ft). The missile itself is accurate to about 75 m (246 ft), which explains why two were typically fired in a salvo. One version, the SA-2E, mounted a 295 kg (650 lb) nuclear warhead of an estimated 15 kiloton yield or a conventional warhead of similar weight.

Typical range for the missile is about 45 km (28 mi), with a maximum altitude around 20,000 m (66,000 ft). The radar and guidance system imposed a fairly long short-range cutoff of about 500 to 1,000 m (1,600 to 3,300 ft), making them fairly safe for engagements at low level.

| Missile | Factory index | Description |

|---|---|---|

| V-750 | 1D | Firing range 7–29 km; Firing altitude 3,000–23,000 m |

| V-750V | 11D | Firing range 7–29 km; Firing altitude 3,000–25,000 m; Weight 2,163 kg; Length 10,726 mm; Warhead weight 190 kg; Diameter 500 mm / 654 mm |

| V-750VK | 11D | Modernized missile |

| V-750VM | 11DM | Missile for firing to aircraft - jammer |

| V-750VM | 11DU | Modernized missile |

| V-750VM | 11DА | Modernized missile |

| V-750M | 20ТD | No specific information available |

| V-750SM | - | No specific information available |

| V-750VN | 13D | Firing range 7–29 km / 7–34 km; Firing altitude 3,000–25,000 m / 3,000–27,000 m; Length 10,841 mm |

| - | 13DА | Missile with new warhead weight 191 kg |

| V-750АK | - | No specific information available |

| V-753 | 13DM | Missile from naval SAM system M-2 Volkhov-M (SA-N-2 Guideline) |

| V-755 | 20D | Firing range 7–43 km; Firing altitude 3,000–30,000 m; Weight 2,360–2,396 kg; Length 10,778 mm; Warhead weight 196 kg |

| V-755 | 20DP | Missile for firing on passive flight-line, Firing range 7–45 km active, 7–56 km passive; Firing altitude 300–30,000 m / 300–35,000 m |

| V-755 | 20DА | Missile with expired guarantee period and remodeled to 20DS |

| V-755OV | 20DO | Missile for taking air samples |

| V-755U | 20DS | Missile with selective block for firing to target in low altitude (under 200 m); Firing altitude 100–30,000 m / 100–35,000 m |

| V-755U | 20DSU | Missile with selective block for firing to target in low altitude (under 200 m) and shortening time preparation missile to fire; Firing altitude 100–30,000 m / 100–35,000 m |

| V-755U | 20DU | Missile with shortening time preparation missile to fire |

| V-759 | 5Ja23 (5V23) | Firing range 6–56 km / 6–60 km / 6–66 km; Firing altitude 100–30,000 m / 100–35,000 m; Weight 2,406 kg; Length 10,806 mm; Warhead weight 197–201 kg |

| V-760 | 15D | Missile with nuclear warhead |

| V-760V | 5V29 | Missile with nuclear warhead |

| V-750IR | - | Missile with pulse radiofuse |

| V-750N | - | Test missile |

| V-750P | - | Experimental missile - with rotate wings |

| V-751 | KM | Experimental missile - flying laboratory |

| V-752 | - | Experimental missile - boosters at the sides |

| V-754 | - | Experimental missile - with semi-active homing head |

| V-757 | 17D | Experimental Missile - with scramjet |

| - | 18D | Experimental Missile - with scramjet[14] |

| V-757Kr | 3M10 | Experimental Missile - version for 2K11 Krug (SA-4 Ganef) |

| V-758 (5 JaGG) | 22D | Experimental Missile - three-stage missile; Weight 3,200 kg; Speed 4.8 mach (1,560 m/s, 5,760 km/h) |

| Korshun | - | Target missile |

| RM-75MV | - | Target missile - for low altitude |

| RM-75V | - | Target missile - for high altitude |

| Sinitsa-23 | 5Ja23 | Target missile |

| Qaher-1 | - | Modified surface-to-surface ballistic missile version developed by Houthis |

Radar

The S-75 typically uses the Spoon Rest early warning radar which has a range of about 275 km (171 mi). The Spoon Rest provides early detection of incoming aircraft, which are then handed off to the acquisition Fan Song radar. These radars, having a range of about 65 km (40 mi), are used to refine the location, altitude, and speed of the hostile aircraft. The Fan Song system consists of two antennas operating on different frequencies, one providing elevation (altitude) information and the other azimuth (bearing) information. Regimental headquarters also include a Spoon Rest, as well as a Flat Face long-range C-band radar and Side Net height-finder. Information from these radars is sent from the regiment down to the battalion Spoon Rest operators to allow them to coordinate their searches. Earlier S-75 versions used a targeting radar known as Knife Rest, which was replaced in Soviet use, but can still be found in older installations.

Major variants

Upgrades to anti-aircraft missile systems typically combine improved missiles, radars, and operator consoles. Usually missile upgrades drive changes to other components to take advantage of the missile's improved performance. Therefore, when the Soviets introduced a new S-75, it was paired with an improved radar to match the missile's greater range and altitude.

- SA-2A; SA-75 Dvina (Двина - Dvina River) with Fan Song-A guidance radar and V-750 or V-750V missiles. Initial deployment began in 1957. The combined missile and booster was 10.6 m (35 ft) long, with a booster having a diameter of 0.65 m (26 in), and the missile a diameter of 0.5 m (20 in). Launch weight is 2,287 kg (5,042 lb). The missile has a maximum effective range of 30 km (19 mi), a minimum range of 8 km (8,000 m), and an intercept altitude envelope of between 450 and 25,000 m (1,480 and 82,020 ft).

- SA-N-2A; S-75M-2 Volkhov-M (Russian Волхов - Volkhov River): Naval version of the A model fitted to the Sverdlov Class cruiser Dzerzhinski. Generally considered unsuccessful and not fitted to any other ships.

- SA-2B; S-75 Desna (Russian Десна - Desna River). This version featured upgraded Fan Song-B radars with V-750VK and V-750VN missiles. This second deployment version entered service in 1959. The missiles were slightly longer than the A versions, at 10.8 m (35 ft), due to a more powerful booster. The SA-2B could engage targets at altitudes between 500 and 30,000 m (1,600 and 98,400 ft) and ranges up to 34 km (21 mi).

- SA-2C; S-75M Volkhov. Once again, the new model featured an upgraded radar, the Fan Song-C, mated to an improved V-750M missile. The improved -2B was deployed in 1961. The V-750M was externally identical to the V-750VK/V-750VN, but it had improved performance for range up to 43 km (27 mi) and reduced lower altitude limits of 400 m (1,300 ft).

- SA-2D; Fan Song-E radar and V-750SM missiles. The V-750SM differed significantly from the A/B/C versions in having new antennas and a longer barometric nose probe. Several other differences were associated with the sustainer motor casing. The missile is 10.8 m (35 ft) long and has the same body diameters and warhead as the SA-2C, but the weight is increased to 2,450 kg (5,400 lb). The effective maximum range is 43 km (27 mi), the minimum range is 6 km (3.7 mi), and the intercept altitude envelope is between 250 and 25,000 m (820 and 82,020 ft). Improved aircraft counter measures led to the development of the Fan Song-E with its better antennas which could cut through heavy jamming.

- SA-2E: Fan Song-E radar and V-750AK missiles. Similar rocket to the D model, but with a bulbous warhead section lacking the older missile's forward fins. The SA-2E is 11.2 m (37 ft) long, has a body diameter of 0.5 m (20 in), and weighs 2,450 kg (5,400 lb) at launch. The missile can be fitted with either a command-detonated 15 kt nuclear warhead or a 295 kg (650 lb) conventional HE warhead.

- SA-2F: Fan Song-F radar and V-750SM missiles. After watching jamming in Vietnam and the Six-Day War render the SA-2 completely ineffective, the existing systems were quickly upgraded with a new radar system designed to help ignore wide-band scintillation jamming. The command system also included a home-on-jam mode to attack aircraft carrying strobe jammers, as well as a completely optical system (of limited use) when these failed. Fs were developed starting in 1968 and deployed in the USSR later that year, while shipments to Vietnam started in late 1970.

- SA-2 FC: Latest Chinese version. It can track six targets simultaneously and is able to control 3 missiles simultaneously.

- S-75M Volga (Russian С-75М Волга - Volga River). Version from 1995.

As previously mentioned, most nations with S-75s have matched parts from different versions or third-party missile systems, or they have added locally produced components. This has created a wide variety of S-75 systems which meet local needs.

- HQ-1 (Hong Qi, Red Flag): Chinese version of SA-2 with additional ECCM electronics to counter the System-12 ECM aboard U-2s flown by the Republic of China Air Force Black Cat Squadron.

- HQ-2: Upgraded HQ-1 with additional ECCM capability to counter the System-13 ECM aboard U-2s flown by Republic of China Air Force Black Cat Squadron. Upgraded HQ-2s remain in service today, and the latest version utilizes Passive electronically scanned array radar designated SJ-202, which is able to simultaneously track and engage multiple targets at 115 km (71 mi) and 80 km (50 mi), respectively. The adoption of multifunction SJ-202 radar has eliminated the need to have multiple, single-function radars, and thus greatly improved the overall effectiveness of the HQ-2 air defence system. A target drone version is designated BA-6.

- HQ-3: Development of HQ-2 with maximum ceiling increased to 30 km, specifically targeted for high altitude and high speed spy planes like SR-71. Maximum range is 42 km and launching weight is around 1 ton, and maximum speed in 3.5 Mach. A total of 150 built before the program ended and the subsequent withdraw of HQ-3 from active service, and the knowledge gained from HQ-3 was used to develop later version of HQ-2.[15][16]

- HQ-4: Further development of HQ-2 from HQ-3, with solid rocket engines, resulting in two third reduction of logistic vehicles needed for a typical SAM battalion with six launchers: from the original more than 60 vehicles for HQ-1/2/3 to just slightly over 20 vehicles for HQ-4. After 33 missiles were built (5 from batch 01, 16 from batch 02, and 12 from batch 03), the program was cancelled, but most of the technologies were continued as separate independent research programs, and these technologies were later used on later Chinese SAMs upgrades and developments such as HQ-2 and HQ-9.[15][17]

- Sayyad-1: Sayyad-1 that is Iranian upgraded version of HQ-2 SAM differ with the Chinese versions in guidance and control subsystems. Sayyad-1 equipped with an about 200-kilogram warhead and has speed of 1,200 meters per second.[18][19]

DF-7

- DF-7/Dongfeng 7/M-7/Project 8610/CSS-8: Chinese surface-to-surface tactical ballistic missile converted from HQ-1/2/3/4. M-7 missile is the only Chinese ballistic missile that can be launched at a slant angle. The rear section of the HQ SAMs are retained, but the forward half is greatly enlarged into a shuttle shape to house bigger warhead and more fuel, while the control surfaces on the forward section are deleted. Armed with a 500 kg warhead (two and half a time of that of the original SAM version) the maximum range of M-7 is 200 km (more than four times of that of the original SAM version).[20][21]

Operators

Current operators

Armenia – 79 Launchers

Armenia – 79 Launchers Azerbaijan – 25

Azerbaijan – 25 Bulgaria – 18

Bulgaria – 18 People's Republic of China

People's Republic of China Cuba

Cuba Egypt – 240, Tayer el-Sabah variant

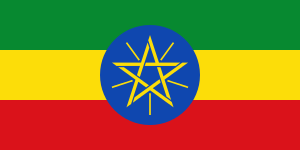

Egypt – 240, Tayer el-Sabah variant Ethiopia – Some developed into self-propelled systems[22]

Ethiopia – Some developed into self-propelled systems[22] Iran – 300+ Launchers, HQ-2J and indigenous Sayyad-1/1A & 2.[23]

Iran – 300+ Launchers, HQ-2J and indigenous Sayyad-1/1A & 2.[23] Kyrgyzstan – few

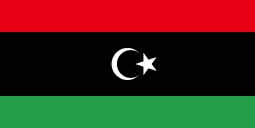

Kyrgyzstan – few Libya[24]

Libya[24].svg.png) Free Libyan Air Force

Free Libyan Air Force Mongolia

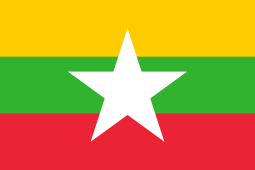

Mongolia Myanmar – 48 next 250 in 2008

Myanmar – 48 next 250 in 2008 North Korea – up to 270

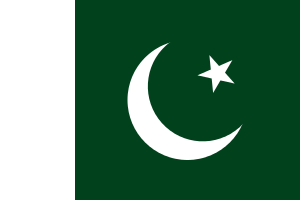

North Korea – up to 270 Pakistan – HQ-2B in service with the Pakistan Air Force.[25][26]

Pakistan – HQ-2B in service with the Pakistan Air Force.[25][26] Romania

Romania Sudan – 700

Sudan – 700 Syria – 275

Syria – 275 Tajikistan – few

Tajikistan – few Vietnam – 280

Vietnam – 280 Yemen

Yemen Zimbabwe

Zimbabwe

Former operators

Afghanistan

Afghanistan Algeria

Algeria Albania – 84 launchers

Albania – 84 launchers Czechoslovakia – 23

Czechoslovakia – 23 East Germany

East Germany Georgia[10]

Georgia[10] Hungary

Hungary Indonesia

Indonesia India

India.svg.png) Iraq

Iraq Moldova – 3 launchers

Moldova – 3 launchers Poland

Poland Russia

Russia

- Most retired in 1991–1996.[1] Missiles used as targets for training. RM-75V/MV Armavir, Sinitsa-1/6(SAM S-75M, missile 20DSU), Sinitsa-23/Korshun (Launcher S-75M3, missile 5YA23), (all in service as of 2011)

Somalia – not operational

Somalia – not operational Soviet Union – passed on to successor states

Soviet Union – passed on to successor states Yugoslavia – passed on to successor states, but retired shortly afterwards

Yugoslavia – passed on to successor states, but retired shortly afterwards

See also

- Project Devil

- Project Nike Similar US medium-high altitude anti-air missile system

References

- 1 2 "C- 75". Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- ↑ "V-75 SA-2 GUIDELINE: Specifications". GlobalSecurity.org. Retrieved 10 August 2010.

- 1 2 Steven J. Zaloga (2007). Red SAM: The SA-2 Guideline Anti-Aircraft Missile. Osprey Publishing. p. 8. ISBN 978-1-84603-062-8.

On October 7, 1959, one of the Taiwanese RB-57Ds was struck at an altitude of 65,600ft (20km) by a salvo of three V-750 missiles

- ↑ Steven J. Zaloga (2007). Red SAM: The SA-2 Guideline Anti-Aircraft Missile. Osprey Publishing. p. 9. ISBN 978-1-84603-062-8.

- ↑ Steven J. Zaloga (2007). Red SAM: The SA-2 Guideline Anti-Aircraft Missile. Osprey Publishing. p. 11. ISBN 978-1-84603-062-8.

- 1 2 "V-750 SA-2 GUIDELINE - Russia / Soviet Nuclear Forces". Federation of American Scientists.

- ↑ Thornton D. Barnes. "U-2 Black Cat Squadron in Taiwan _ ROCAF U-2 Operations over China". Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- ↑ "Cuban Missile Crisis". United States Air Force. 23 October 2007. Archived from the original on 23 July 2012. Retrieved 10 August 2010.

- ↑ http://www.airforce-magazine.com/MagazineArchive/Pages/2010/July%202010/0710weasels.aspx

- 1 2 "Moscow Defense Brief". Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- ↑ https://www.tasnimnews.com/en/news/2015/12/22/950631/yemen-adapts-surface-to-air-missile-to-hit-ground-targets

- ↑ http://alert5.com/2015/12/14/yemen-modified-s-75-missiles-into-unguided-rockets-launched-them-into-saudi-arabia/

- ↑ Zaloga, Steven J. Red SAM: The SA-2 Guideline Anti-Aircraft Missile. Osprey Publishing, 2007. ISBN 978-1-84603-062-8. P. 22

- ↑ Wade, Mark (2008). "18D". Retrieved May 24, 2010.

- 1 2 "HQ-3 & HQ-4". Retrieved 2010-06-17.

- ↑ HQ-3

- ↑ "HQ-4". lt.cjdkby.net. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- ↑ http://www.mashreghnews.ir/fa/news/64468

- ↑ http://www.mashreghnews.ir/fa/news/316229

- ↑ "M-7". china.com. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- ↑ "DF-7 / M-7 / 8610 / CSS-8". Globalsecurity. Retrieved 2015-02-02.

- ↑ Binnie, Jeremy. "Ethiopia turns S-75 SAMs into self-propelled systems". IHS Jane's 360. IHS Jane's. Retrieved 4 May 2016.

- ↑ http://presstv.com/detail/175098.html

- ↑ "The Libyan SAM Network". 2010-05-11. Retrieved 2011-02-21.

- ↑ Kapila, Viney (2002). The Indian Air Force, a Balanced Strategic and Tactical Application. Prabhat Prakashan. ISBN 9788187100997.

- ↑ Zaloga, Steven (2007). Red SAM: The SA-2 Guideline Anti-Aircraft Missile. Osprey Publishing. p. 40. ISBN 9781846030628.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to S-75. |

| Wikisource has several original texts related to: Audio recordings and transcripts with comments of actual Wild Weasel combat missions over Vietnam |

- Russian site on the S-75 from Said Aminov "Vestnik PVO" (in Russian)

- Russian site on the S-75 from Vitaly Kuzmin "Military Paritet" (in Russian)

- S-75M3 Volkhov (SA-2e Guideline) Simulator