Hong–Ou–Mandel effect

The Hong–Ou–Mandel effect is a two-photon interference effect in quantum optics which was demonstrated in 1987 by three physicists from the University of Rochester: Chung Ki Hong, Zhe Yu Ou and Leonard Mandel.[1] The effect occurs when two identical single-photon waves enter a 50:50 beam splitter, one in each input port. When the photons are identical they will extinguish each other. If they become more distinguishable, the probability of detection will increase. In this way the interferometer can accurately measure bandwidth, path lengths and timing.

Quantum-mechanical description

Physical description

When a photon enters a beam splitter, there are two possibilities: it will either be reflected or transmitted. The relative probabilities of transmission and reflection are determined by the reflectivity of the beam splitter. Here, we assume a 50:50 beam splitter, in which a photon has equal probability of being reflected and transmitted.

Next, consider two photons, one in each input mode of a 50:50 beam splitter (see figure 1). There are four possibilities for the photons to behave: 1) The photon coming in from above is reflected and the photon coming in from below is transmitted; 2) Both photons are transmitted; 3) Both photons are reflected; 4) The photon coming in from above is transmitted and the photon coming in from below is reflected. We assume now that the two photons are identical in their physical properties (i.e., polarization, spatio-temporal mode structure, and frequency).

Since the state of the beam splitter does not "record" which of the four possibilities actually happens, Feynman rules dictates that we have to add all four possibilities at the amplitude level. In addition, reflection off the bottom side of the beam splitter introduces a relative phase shift of −1 in the associated term in the superposition. This is required by the reversibility (or unitarity) of the quantum evolution of the beam splitter. Since the two photons are identical, we cannot distinguish between the output states of possibilities 2 and 3 in figure 1, and their relative minus sign ensures that these two terms cancel. This can be interpreted as destructive interference.

Mathematical description

Consider two optical modes a and b that carry annihilation and creation operators , , and , . Two identical photons in different modes can be described by the Fock states

where is a single-photon state. When the two modes a and b are mixed in a 50:50 beam splitter, they turn into new modes c and d, and the creation and annihilation operators transform accordingly:

The relative minus sign appears because the beam splitter is a unitary transformation. This can be seen most clearly when we write the two-mode beam splitter transformation in matrix form:

Unitarity of the transformation now means unitarity of the matrix. Physically, this beam splitter transformation means that reflection off one surface induces a relative phase shift of −1 with respect to reflection off the other side of the beam splitter (see the Physical Description above). Similar transformations hold for the annihilation operators.

When two photons enter the beam splitter, one on each side, the state of the two modes becomes

Since the commutator of the two creation operators and vanishes, the surviving terms in the superposition are and . Therefore, when two identical photons enter a 50:50 beam splitter, they will always exit the beam splitter in the same (but random) output mode.

Experimental signature

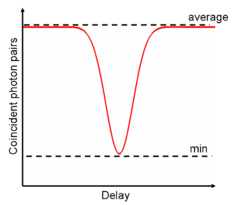

Customarily the Hong–Ou–Mandel effect is observed using two photodetectors monitoring the output modes of the beam splitter. The coincidence rate of the detectors will drop to zero when the identical input photons overlap perfectly in time. This is called the Hong–Ou–Mandel dip, or HOM dip, shown in Figure 2. The coincidence count reaches a minimum, indicated by the dotted line. The minimum drops to zero when the two photons are perfectly identical in all properties. When the two photons are perfectly distinguishable, the dip completely disappears. The precise shape of the dip is directly related to the power spectrum of the single-photon wave packet, and is therefore determined by the physical process of the source. Common shapes of the HOM dip are Gaussian and Lorentzian.

A classical analog to the HOM effect occurs when two coherent states (e.g. laser beams) interfere at the beamsplitter. If the states have a rapidly varying phase difference (i.e. faster than the integration time of the detectors) then a dip will be observed in the coincidence rate equal to one half the average coincidence count at long delays. (Nevertheless, it can be further reduced with a proper discriminating trigger level applied to the signal.) Consequently, to prove that destructive interference is two-photon quantum interference rather than a classical effect, the HOM dip must be lower than one half.

The Hong–Ou–Mandel effect can be directly observed using single-photon-sensitive, intensified cameras. Such cameras have the ability to register single photons as bright spots clearly distinguished from the low-noise background. In Figure 3 the pairs of photons are registered in the middle of the Hong-Ou-Mandel dip.[2] In most cases they appear grouped in pairs either on the left or right hand side, corresponding to two output ports of a beam-splitter. Occasionally a coincidence event occurs manifesting a residual distinguishability between the photons.

Applications and experiments

The Hong–Ou–Mandel effect can be used to test the degree of indistinguishability of the two incoming photons. When the HOM dip in figure 2 reaches all the way down to zero coincidence counts, the incoming photons are perfectly indistinguishable, whereas if there is no dip the photons are distinguishable. In 2002, the Hong–Ou–Mandel effect was used to demonstrate the purity of a solid-state single-photon source by feeding two successive photons from the source into a 50:50 beam splitter.[3] The interference visibility V of the dip is related to the states of the two photons and by:

If then the visibility is equal to the purity of the photons. In 2006, an experiment was performed in which two atoms independently emitted a single photon each. These photons subsequently produced the Hong–Ou–Mandel effect.[4]

The Hong–Ou–Mandel effect also underlies the basic entangling mechanism in linear optical quantum computing, and the two-photon quantum state that leads to the HOM dip is the simplest non-trivial state in a class called NOON states.

In 2015 the Hong–Ou–Mandel effect for photons was directly observed with spatial resolution using an sCMOS camera with an image intensifier.[2] Also in 2015 the effect was observed with helium-4 atoms.[5]

The HOM effect can be used to measure the biphoton wave function from a spontaneous four-wave mixing process.[6]

In 2016 a frequency converter for photons demonstrated the Hong–Ou–Mandel effect with different-color photons.[7]

Three photon interference

Three photon interference effect has been identified in experiments.[8][9][10]

See also

References

- ↑ C. K. Hong; Z. Y. Ou & L. Mandel (1987). "Measurement of subpicosecond time intervals between two photons by interference". Phys. Rev. Lett. 59 (18): 2044–2046. Bibcode:1987PhRvL..59.2044H. PMID 10035403. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.59.2044.

- 1 2 3 M. Jachura; R. Chrapkiewicz (2015). "Shot-by-shot imaging of Hong–Ou–Mandel interference with an intensified sCMOS camera". Opt. Lett. 40 (7): 1540–1543. PMID 25831379. doi:10.1364/ol.40.001540.

- ↑ C. Santori; D. Fattal; J. Vucković; G. S. Solomon & Y. Yamamoto (2002). "Indistinguishable photons from a single-photon device". Nature. 419 (6907): 594–597. PMID 12374958. doi:10.1038/nature01086.

- ↑ J. Beugnon; M. P. A. Jones; J. Dingjan; B. Darquié; G. Messin; A. Browaeys & P. Grangier (2006). "Quantum interference between two single photons emitted by independently trapped atoms". Nature. 440 (7085): 779–782. PMID 16598253. doi:10.1038/nature04628.

- ↑ R. Lopes; A. Imanaliev; A. Aspect; M. Cheneau; D. Boiron & C. I. Westbrook (2015). "Atomic Hong–Ou–Mandel experiment". Nature. 520 (7545): 66–68. PMID 25832404. arXiv:1501.03065

. doi:10.1038/nature14331.

. doi:10.1038/nature14331. - ↑ P. Chen; C. Shu; X. Guo; M. M. T. Loy & S. Du (2015). "Measuring the biphoton temporal wave function with polarization-dependent and time-resolved two-photon interference". Phys. Rev. Lett. 114 (1): 010401. PMID 25615453. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.114.010401.

- ↑ T. Kobayashi; R. Ikuta; S. Yasui; S. Miki; T. Yamashita; H. Terai; T. Yamamoto; M. Koashi & N. Imoto (2016). "Frequency-domain Hong–Ou–Mandel interference". Nature Photonics. 10: 441–444. arXiv:1601.00739

. doi:10.1038/nphoton.2016.74.

. doi:10.1038/nphoton.2016.74. - ↑ Sewell, Robert (2017-04-10). "Viewpoint: Photonic Hat Trick". Physics. 10.

- ↑ Agne, Sascha; Kauten, Thomas; Jin, Jeongwan; Meyer-Scott, Evan; Salvail, Jeff Z.; Hamel, Deny R.; Resch, Kevin J.; Weihs, Gregor; Jennewein, Thomas (2017-04-10). "Observation of Genuine Three-Photon Interference". Physical Review Letters. 118 (15): 153602. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.118.153602.

- ↑ Menssen, Adrian J.; Jones, Alex E.; Metcalf, Benjamin J.; Tichy, Malte C.; Barz, Stefanie; Kolthammer, W. Steven; Walmsley, Ian A. (2017-04-10). "Distinguishability and Many-Particle Interference". Physical Review Letters. 118 (15): 153603. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.118.153603.

External links

- Lectures on Quantum Computing: Interference (2 of 6) - David Deutsch lecture video, video of related experiment (a single photon in a sharp direction is split, mirrored and rejoined in a second splitter (joiner) output in the sharp direction).

- Can Two-Photon Interference be Considered the Interference of Two Photons? - Discussion of the interpretation of the HOM interferometer results.

- YouTube animation showing HOM effect in a semiconductor device.

- YouTube movie showing experimental results of HOM effect observed on a camera.