Honey War

Coordinates: 40°35′N 93°28′W / 40.58°N 93.46°W

| Honey War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| None | None | ||||||||

The Honey War was a bloodless territorial dispute in 1839 between Iowa, then Iowa Territory, and Missouri over their border.

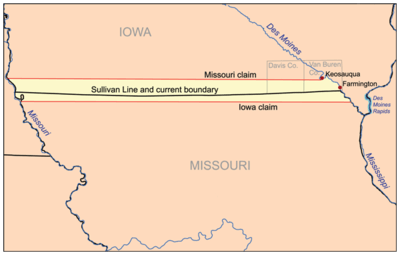

The dispute over a 9.5-mile (15.3 km) wide strip running the entire length of the border, caused by unclear wording in the Missouri Constitution on boundaries, misunderstandings over the survey of the Louisiana Purchase, and a misreading of Native American treaties, was ultimately decided by the United States Supreme Court in Iowa's favor. The decision was to affirm a nearly 30-mile (48 km) jog in the nearly straight line border between extreme southeast Iowa and northeast Missouri at Keokuk, Iowa that is now Iowa's southernmost point.

Before the issue was settled, militias from both sides faced each other at the border, a Missouri sheriff collecting taxes in Iowa was incarcerated, and three trees containing beehives were cut down.

The Southern Boundary of Iowa [1]

Early Wars (Iowa)--Iowa Pathways [2]

Timeline

- 1803: Louisiana Purchase

- 1804: Treaty of St. Louis - Sac and Fox tribes cede Missouri from the mouth of the Gasconade River through Illinois and Wisconsin

- 1808: Treaty of Fort Clark - Osage Nation cedes Missouri and Arkansas east of Fort Osage

- 1812-1815: War of 1812 - Tribes protesting the treaties side with the British in Missouri and Mississippi Valley skirmishes

- 1814: Treaty of Ghent ends the war and requires tribes to be treated as before the war

- 1815: Treaties of Portage des Sioux includes wording that the Osage, Sac and Fox agree to their earlier treaties

- 1816: John C. Sullivan surveys the Indian Boundary Line (1816) from the mouth of the Kansas River in modern-day Kansas City, Missouri to approximately Sheridan, Missouri and then east to the Des Moines River near Farmington, Iowa

- 1818: Missouri considers various boundary options for statehood.

- 1820: Missouri enters the Union with its western boundary being the Indian Boundary Line and its northern boundary being the Sullivan Line. Wording in the Constitution refers to the rapids on the river Des Moines which some perceive as ambiguous since the Des Moines has no rapids but the Mississippi nearby has rapids called the Des Moines Rapids.

- 1824: Sac and Fox cede all remaining land in Missouri and ceded the land south of the Sullivan Line between the Des Moines and Mississippi as Half Breed Tract. Missouri makes no effort to extend its claim to Half Breed Tract.

- 1830: Indian Removal Act - Efforts begin to remove all tribes to west of the Indian Boundary Line

- 1832: Black Hawk War as tribes resist the removal order

- 1834: Congress opens up Half Breed Tract to settlement but Missouri again makes no claim on the territory.

- 1836: Iowa is removed from Michigan Territory to Wisconsin Territory

- 1836: The federal government in the Platte Purchase buys the land west of the Indian Boundary line and it is annexed to Missouri with its northern border being the Sullivan Line.

- 1838: Iowa Territory is organized

- 1839: According to legend a Missouri tax collector in Iowa cuts down three hollow trees containing honey bee hives to collect the honey in lieu of taxes.

- 1839: Clark County, Missouri sheriff Uriah S. ("Sandy") Gregory is arrested by Van Buren County, Iowa sheriff while attempting to collect Missouri taxes in the disputed territory.

- 1839: Militias from both sides assemble at the border

- 1839: Matter is referred to the U.S. Supreme Court

- 1846: Iowa enters the Union

- 1849: Supreme Court issues an opinion that since Missouri never challenged its straight line border ending at the Des Moines River for more than 10 years, the border was valid. The court further upholds the Sullivan Line as the correct border but orders it resurveyed to correct quirks in Sullivan's Line which had jogs.

- 2005: Following various disputes, the State of Missouri contracts to have the border resurveyed, which finds many of the markers from the Supreme Court survey of 1850.[3]

Background

Native American treaties

The first major Native American treaties following the Louisiana Purchase in 1803 were the Treaty of St. Louis in 1804 in which the Sac and Fox ceded much of northeast Missouri as well as southern Wisconsin and northern Illinois and the Treaty of Fort Clark in 1808 in which the Osage Nation ceded most of Missouri and Arkansas.

The United States made no formal efforts to survey the land. During the War of 1812 Native Americans sided with the British. When the war turned out to be a stalemate, the Treaty of Ghent in 1815 required that the tribes be returned to the same status they had before the war.

Various tribes met with United States representatives at Portage Des Sioux, Missouri, in 1815 to formally end the war. While most of the Treaties of Portage des Sioux were innocuous treaties with wording about lasting friendship, the treaties with the Sac, Fox and Osage also included a paragraph indicating agreement to abide by the earlier treaties.

With that in place the United States began plans to survey its territory. In the Treaty of Fort Clark, the Osage had ceded all land east of Fort Clark near Sibley, Missouri. The treaty permitted the United States to survey the new land and they were to "adjust" the boundaries for a starting point 23 miles (37 km) west to the mouth of the Kansas River with the Missouri River in Kansas City, Missouri on the far bank opposite Kaw Point.

Sullivan Survey

In 1816 United States surveyor John C. Sullivan was instructed to survey a line north from the mouth for 100 miles (160 km) and then proceed east to the Des Moines River. In addition to being a round number the 100-mile (160 km) line Indian Boundary Line (1816) also lined up in the east with the 2.4 feet (0.73 m) deep Des Moines Rapids on the Mississippi River just south of Fort Madison, Iowa, that was the northern end of navigation on the Mississippi and it also lined up with the westward adjusted boundary from the mouth of the Gasconade River the Sac had ceded in 1808. The land on the east side of the Des Moines River was the site of a Sac village which had not been ceded.

Sullivan erected survey markers along the line. The northwest corner of Missouri was established in a marker near Sheridan, Missouri. From there he continued east establishing the Sullivan Line to the Des Moines River just south of Farmington, Iowa, where he made no note of rapids and called it a "small river with shallow gentle water." He did continue his survey another 20 miles (32 km) to the Mississippi.

Confusion over the terms of the Des Moines Rapids on the Mississippi and the phrase rapids on the Des Moines River was to contribute to the border skirmish.

Missouri boundaries

When Missouri applied for statehood first in 1818 various proposals for boundaries were put forth including a western boundary at the mouth of the Nodaway River about 30 miles (48 km) west and the mouth of the Rock River (Illinois) opposite Rock Island, Illinois. Missouri was already going to be the largest state in area when it entered the Union and there was concern about making it even bigger. Sullivan was a delegate to the convention that was to ultimately declare the boundaries to be the two lines he had drawn.

The constitution defined the boundary as:

- Beginning in the middle of the Mississippi River, on the parallel of thirty-six degrees of north latitude; thence west along the said parallel of latitude to the St. Francois River; thence up and following the course of that river, in the middle of the main channel thereof, to the parallel of latitude of thirty-six degrees and thirty minutes; thence west along the same to a point where the said parallel is intersected by a meridian line passing through the middle of the mouth of the Kansas River, where the same empties into the Missouri River; thence, from the point aforesaid, north along the said meridian line, to the intersection of the parallel of latitude which passes through the rapids of the River Des Moines, making said line correspond with the Indian boundary-line; thence east from the point of intersection last aforesaid, along the said parallel of latitude, to the middle of the channel of the main fork of the said River Des Moines; thence down along the middle of the main channel of the said River Des Moines to the mouth of the same, where it empties into the Mississippi River; thence due east to the middle of the main channel of the Mississippi River; thence down and following the course of the Mississippi River, in the middle of the main channel thereof, to the place of beginning.[4]

The wording of the boundary "extending westward of the rapids of the river Des Moines" was to cause confusion.

In the Treaty of Washington (1824) the Sac and Fox ceded their land in Missouri. The land below the Sullivan Line between the Des Moines and Mississippi was set aside as Half Breed Tract.

In the Indian Removal Act of 1830, all tribes were moved west and south of the line Sullivan had drawn.

In 1834 Half Breed Tract was opened to public settlement. This, along with the transfer of the territory of modern-day Iowa to the Wisconsin Territory, was to spur Missouri to reconsider its northern border, first by extending its border west to the Missouri River in the Platte Purchase in northwest Missouri and then by reconsidering the northeast corner.

The "War"

In 1837 the Missouri General Assembly ordered the line to be resurveyed. When Wisconsin Territory refused to participate in the survey, J.C. Brown began a survey in which he ignored the traditional definition of the rapids below Fort Madison on the Mississippi and instead looked for rapids on the Des Moines River itself and identified the rapids as being at Keosauqua, Iowa, about 9.5 miles (15.3 km) into modern Iowa.

As the dispute heated up, Missouri was to note there were rapids on the Des Moines all the way to Des Moines, Iowa. Meanwhile, Iowa was to maintain its ownership extended to a line about 15 miles (24 km) into modern Missouri at the mouth of the Des Moines.

Tax agents from Kahoka, Missouri, tried to collect taxes in what is now Van Buren County, Iowa, and Davis County, Iowa. The Iowa residents, allegedly carrying pitchforks, chased away the tax collectors who, legend has it, chopped down three honey bee trees in what is now Lacey-Keosauqua State Park to collect the honey for partial payment.

Missouri governor Lilburn Boggs sent 11 mounted members of the 14th Division of the Missouri State Militia under Major General David Willock, from Palmyra, Missouri, to the disputed border to protect the tax collector.[5] General Willock was unwilling to shed blood over an issue that should have been resolved peacefully by the governors or by Congress, and an Iowa mob succeeded in capturing the sheriff of Clark County, Missouri, and incarcerated him in the Muscatine, Iowa, jail. The Iowa militia was also called out by Iowa Territory governor Robert Lucas. Authorization for a total payment of $46 to the Missouri Militia was for 7 days in active service.

According to one description about the Iowans:[6]

- in the ranks were to be found men armed with blunderbusses, flintlocks, and quaint old ancestral swords that had probably adorned the walls for many generations. One private carried a plow coulter over his shoulder by means of a log chain, another had an old-fashioned sausage stuffer for a weapon, while a third shouldered a sheet iron sword about six feet long.

The two governors agreed to allow Congress resolve the issue. An arbitrary line was drawn between the two positions. However, when Iowa entered the Union Congress was to rule the border was in fact at the Mississippi confluence, a position that was upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court in State of Missouri v. State of Iowa, 48 U.S. 660 (1849).[7][8]

See also

- List of incidents of civil unrest in the United States

- State of Missouri v. State of Iowa (1849)

- Sullivan Line

References

- ↑ http://ir.uiowa.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1986&context=annals-of-iowa

- ↑ http://www.iptv.org/iowapathways/mypath.cfm?ounid=ob_000260

- ↑ Hayes, Troy (March–April 2006), "Missouri-Iowa Boundary Line Investigation" (PDF), The American Surveyor, Cheves Media, retrieved 2009-03-31

- ↑ STATE OF MISSOURI v. STATE OF IOWA, 48 U.S. 660 (1849)

- ↑ Laws of Missouri, First Session of the Twelfth General Assembly, 1843, page 89

- ↑ The Territorial Militia - History of The Iowa National Guard by Stephen N. Kallestad

- ↑ Stories of Iowa for Boys and Girls by Bruce E. Mahan - 1931 - reprinted on Iowa History Project

- ↑ Country Facts and Folklore By Andy Reddick (republished on rootsweb)

Further reading

- Supreme Court decision

- One Sloppy Land Surveyor Almost Caused a War Between Missouri and Iowa

- Everett, Derek R. (2008, Fall). To Shed Our Blood for Our Beloved Territory: The Iowa-Missouri Borderland. The Annals of Iowa, 67(4), 269–297.