Homo heidelbergensis

| Homo heidelbergensis Temporal range: 0.6–0.2 Ma | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Synapsida |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Haplorhini |

| Infraorder: | Simiiformes |

| Family: | Hominidae |

| Genus: | Homo |

| Species: | H. heidelbergensis |

| Binomial name | |

| Homo heidelbergensis Schoetensack, 1908 | |

Homo heidelbergensis is an extinct species of the genus Homo that lived in Africa, Europe and western Asia between 600,000 and 200,000 years ago.

The skulls of this species share features with both Homo erectus and anatomically modern Homo sapiens; its brain was nearly as large as that of Homo sapiens.[1] Although the first discovery – a mandible – was made in 1907 near Heidelberg in Germany where it was described and named by Otto Schoetensack, the vast majority of H. heidelbergensis fossils have been found after 1996.[2] The Sima de los Huesos cave at Atapuerca in northern Spain holds particularly rich layers of deposits where excavations are still in progress.[3][4][5][6]

Neanderthals, Denisovans, and modern humans are all considered to have descended from Homo heidelbergensis[7][8] that appeared around 700,000 years ago in Africa. Fossils have been recovered in Ethiopia, Namibia and South Africa. Between 400,000 and 300,000 years ago a group of Homo heidelbergensis migrated into Europe and West Asia via yet unknown routes and eventually evolved into Neanderthals. Archaeological sites exist in Spain, Italy, France, England, Germany, Hungary and Greece.[9] Another Homo heidelbergensis group ventured eastwards into continental Asia, eventually developing into Denisovans. The African Homo heidelbergensis (Homo rhodesiensis) population evolved into Homo sapiens 300,000 to 200,000 years ago, then migrated into Europe and Asia in a second wave at some point between 125,000 and 60,000 years ago.[10][11][12][13][14]

The correct assignment of many fossils to a particular chronospecies is difficult and often controversies ensue among paleoanthropologists due to the absence of universally accepted dividing lines (autapomorphies) between Homo erectus, Homo heidelbergensis and Neanderthals. Some researchers suggest that the finds associated to Homo heidelbergensis are mere variants of Homo erectus.[15][16][17]

Morphology and interpretations

Both Homo antecessor and Homo heidelbergensis are likely to have descended from the morphologically very similar Homo ergaster from Africa. But because H. heidelbergensis had a larger brain-case – with a typical cranial volume of approximately 1,250 cm3 (76 cu in) – and had more advanced tools and behavior, it has been given a separate species classification.[18] "The anatomy [of H. heidelbergensis] is clearly more primitive than that of Neanderthal, but the harmoniously rounded dental arch and the complete row of teeth...already typically human."[19]

.jpg)

For more than half a century many experts were reluctant to accept Homo heidelbergensis as a separate taxon due to the rarity of specimens, which prevented sufficient informative morphological comparisons and the distinction of H. heidelbergensis from other known human species.[20] The species name "heidelbergensis" only experienced a renaissance with the many discoveries of the past 30 years and appears now to be recognized by an increasing number of researchers.[21][22] Yet some researchers hold the contrary view that the evolutionary development in Africa and Europe was a gradual process from H. erectus via the findings assigned to H. heidelbergensis towards Neanderthal. Any form of segregation is considered arbitrary, which is why these researchers forgo the name H. heidelbergensis altogether.[23] Paleoanthropologists often refer to the uncertainties surrounding the specimens, their dating and morphology, as “the muddle in the middle.”[24]

The fact that there seem to be no clear transitions makes it difficult to draw up a list of unique characteristics of H. heidelbergensis that distinguishes it from H. erectus and H. neanderthalensis. In general, the findings show a continuation of evolutionary trends that are emerging from around the Lower into Middle Pleistocene. Along with changes in the robustness of cranial and dental features, a remarkable increase in brain size from H. erectus towards H. heidelbergensis is noticeable.[25]

Male H. heidelbergensis averaged about 1.75 m (5 ft 9 in) tall and 62 kg (136 lb). Females averaged 1.57 m (5 ft 2 in) and 51 kg (112 lb).[26] A reconstruction of 27 complete human limb bones found in Atapuerca (Burgos, Spain) has helped to determine the height of H. heidelbergensis compared with H. neanderthalensis; the conclusion was that these H. heidelbergensis averaged about 170 cm (5 ft 7in) in height and were only slightly taller than Neanderthals.[27][28] According to Lee R. Berger of the University of the Witwatersrand, numerous fossil bones indicate some populations of H. heidelbergensis were "giants" routinely over 2.13 m (7 ft) tall and inhabited South Africa between 500,000 and 300,000 years ago.[29][30][31]

Otto Schoetensack described the mandible Mauer 1 in his original species description in 1907:[32]

The "nature of our object" reveals itself "at first sight" since "a certain disproportion between the jaw and the teeth" is obvious: "The teeth are too small for the bone. The available space would allow for a far greater flexibility of development" and "It shows a combination of features, which has been previously found neither on a recent nor a fossil human mandible. Even the scholar should not be blamed if he would only reluctantly accept it as human: Entirely missing is the one feature, which is regarded as particularly human, namely an outer projection of the chin portion, yet this deficiency is found to be combined with extremely strange dimensions of the mandibular body. The actual proof that we are dealing with human parts here only lies within the nature of the dentition. The completely preserved teeth bear the stamp 'human' as evidence: The canines show no trace of a stronger expression in relation to the other groups of teeth. They suggest a moderate and harmonious co-evolution, as it is the case in recent humans."

Social behavior

Recent findings[33] in a pit in Atapuerca (Spain) of 28 human skeletons suggest that H. heidelbergensis might have been the first species of the Homo genus to bury its dead.[34]

Steven Mithen[35] believes that H. heidelbergensis, like its descendant H. neanderthalensis, acquired a pre-linguistic system of communication. No forms of art have been uncovered, although red ochre, a mineral that can be used to mix a red pigment which is useful as a paint, has been found at Terra Amata excavations in the south of France.

Language

The morphology of the outer and middle ear suggests they had an auditory sensitivity similar to modern humans and very different from chimpanzees. They were probably able to differentiate between many different sounds.[36] Dental wear analysis suggests they were as likely to be right-handed as modern people.[37]

H. heidelbergensis was a close relative (probably a descendant) of Homo ergaster. H. ergaster is thought to be the first hominin to vocalize using a mix of vowels and consonants to communicate with other members of its species,[35] and that as H. heidelbergensis developed, more sophisticated culture proceeded from this point.[38]

Evidence of hunting

A 300,000-year-old archeological site in Schöningen, Germany contained eight exceptionally well-preserved spears for hunting, and various other wooden tools. Five-hundred-thousand-year-old hafted stone points used for hunting are reported from Kathu Pan 1 in South Africa, tested by way of use-wear replication.[39] This find could mean that modern humans and Neanderthals inherited the stone-tipped spear, rather than developing the technology independently.[39][40]

Evolution

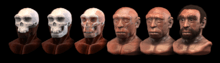

_1.jpg)

Around 700,000 years ago Homo erectus evolved in Africa into a new human species, Homo heidelbergus, with a much bigger brain who used well-manufactured stone tools (known as the Acheulean culture) which, in a second propagation wave (out of Africa II), subsequently migrated to Europe, including Germany and England. Their robust build and excellent hunting tools appeared to be well suited to dealing with the climate fluctuations in Europe. H. heidelbergensis hominins evolved into the Neanderthals approximately 250,000 to 300,000 years ago during the Wolstonian Stage,[41] however, comparison of Neanderthal and modern human DNA suggests divergence from a common ancestor (likely H. heidelbergensis) at least 400,000 years ago.[5]

Because of the migration of H. heidelbergensis out of Africa and into Europe, the two populations were mostly isolated during the Wolstonian Stage and Ipswichian Stage, the last of the prolonged Quaternary glacial periods. H. sapiens probably diverged between 200,000 and 100,000 years ago in Africa. Such fossils as the Atapuerca skull in Spain and the Kabwe skull in modern-day Zambia bear witness to the two branches of the H. heidelbergensis tree.[42] Thus, "the picture emerging is one of Homo erectus as a widespread, polytypic species, with groups persisting longer in some regions than in others. The pattern documented in China and especially in Java contrasts with that in the West, where Homo erectus seems to disappear from the record at a relatively early date".[43]

Homo neanderthalensis retained most of the features of Homo heidelbergensis after its divergent evolution.[44] Although shorter, Neanderthals were more robust, had large brow-ridges, a slightly protruding face, and lack of prominent chin. With a virtually identical cranial capacity to Cro-Magnon, they also had a larger brain than all other hominins. Homo sapiens, on the other hand, have the smallest brows of any known hominin, are taller and more gracile, and have a flat face with a protruding chin. H. sapiens have a larger brain than H. heidelbergensis, and a smaller brain than H. neanderthalensis, on average.[30] To date, H. sapiens is the only known hominin with a high forehead, flat face, and thin, flat brows.[45]

Today's researchers, such as Chris Stringer consider it justifiable to declare Homo heidelbergensis as an independent chronospecies, as some used to hold the view that it is a cladistic ancestor to other Homo forms, sometimes improperly linked to distinct species in terms of populational genetics.[46][47]

In 2013 researchers published sequenced DNA from fossils in the Sima de los Huesos cave in the Atapuerca Mountains, all classified as members of H. heidelbergensis and thought to have given rise to Neanderthal. "The [] fossils’ identity suddenly became complicated when a study of the maternally inherited mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) from one of the bones revealed that it did not resemble that of a Neanderthal. Instead, it more closely matched the mtDNA of a Denisovan...".[48]

In an article of 2015, Matthias Meyer of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology states: “Indeed, the Sima de los Huesos specimens are early Neanderthals or related to early Neanderthals,” after his team had scanned this DNA for markers found only in Neanderthals, Denisovans or modern humans, they found that the nuclear genomes of those specimens were significantly more similar to Neanderthals. "And that suggests the Neanderthal-Denisovan split happened before 430,000 years ago".[49]

Some scenarios of survival include:

- H. heidelbergensis > H. neanderthalensis [50]

- H. heidelbergensis > Homo sp. (Denisovans)[51]

- H. heidelbergensis > Homo rhodesiensis > Homo sapiens idaltu > H. sapiens sapiens [52]

|

Fossils

Mauer 1

The first fossil discovery of this species was made on October 21, 1907, and came from Mauer, Germany. Here, the workman Daniel Hartmann spotted a jaw in a sandpit. The jaw (Mauer 1) was in good condition except for the missing premolar teeth, which were eventually found near the jaw. The workman gave it to Professor Otto Schoetensack from the University of Heidelberg, who identified and named the fossil.[53]

The next H. heidelbergensis remains were found in Steinheim an der Murr, Germany (the Steinheim Skull, 350kya); Arago, France (Arago 21); Petralona, Greece; Ciampate del Diavolo, Italy; Dali, Jinniushan and Maba (Guangdong), China. In 1925–1926 Francis Turville-Petre unearthed the "Galilee skull" at Mugharet el-Zuttiyeh in Israel, which was the first ancient hominin fossil found in Western Asia.[54]

Kabwe skull

.jpg)

Kabwe 1, also called the Broken Hill skull, was assigned by Arthur Smith Woodward in 1921 as the type specimen for Homo rhodesiensis; today most scientists now assign it to Homo heidelbergensis.[55][56] The cranium was found in a lead and zinc mine in Broken Hill, Northern Rhodesia (now Kabwe, Zambia) in 1921 by Tom Zwiglaar, a Swiss miner. In addition to the cranium, an upper jaw from another individual, a sacrum, a tibia, and two femur fragments were also found. The skull was dubbed "Rhodesian Man" at the time of the find, but is now commonly referred to as the Broken Hill skull or the Kabwe cranium.

Saldanha cranium

Saldanha cranium or Elandsfontein cranium are fossilized remains of a hominin species considered to be Homo heidelbergensis. The remains were found in 1954 in Elandsfontein, located in the Hopefield of South Africa. To date it remains the southernmost hominid find.[57]

Petralona 1

- discovered in 1959

- Site: Petralona Cave, Greece

- Age: Between 350,000 and 150,000 years old[58]

Arago 21

On 22 July 1971 near the village of Tautavel in Pyrénées-Orientales, the team of Prof. Henry de Lumley discovered a 450,000 year old human skull following seven years of excavations in a mountain cave called Caune de l'Arago. Since the discovery of Tautavel Man (Homo erectus tautavelensis), annual excavations have revealed more than one hundred human fossils, making this cave one of the largest prehistoric deposits in the world. The skeletons at Tautavel are among the oldest human remains ever discovered in Europe. The Arago Cave, very close to the village, was occupied periodically between 690,000 and 35,000 years ago. Although scientist do not explicitly relate these finds to H. heidelbergensis, morphological characteristics are those of humans who preceded Neanderthal.[59]

Bodo Cranium

The Bodo cranium was found by members of an expedition led by Jon Kalb in 1976 at Bodo D'ar, Awash River valley of Ethiopia.[60] The initial discovery - a lower face - was made by Alemayhew Asfaw and Charles Smart. Two weeks later, Paul Whitehead and Craig Wood found the upper portion of the face. The skull is 600,000 years old.[61]

Boxgrove Man

In 1994 British scientists unearthed a lower hominin tibia bone of Boxgrove Man a few miles away from the English Channel, along with hundreds of ancient hand axes, at the Boxgrove Quarry site. This partial leg bone is dated to between 478,000 and 524,000 years old.[62] Several H. heidelbergensis teeth were also found in subsequent seasons. H. heidelbergensis was the early proto-human species that occupied both France and Great Britain at that time; these locales were connected by a landmass during that epoch.

The tibia had been gnawed by a large carnivore, suggesting that the man had been killed by a lion or wolf, or that his unburied corpse had been scavenged after death.[63]

Sima de los Huesos

Beginning in 1992, a Spanish team has located more than 5,500 human bones dated to an age of at least 350,000 years in the Sima de los Huesos site in the Sierra de Atapuerca in northern Spain. The pit contains fossils of perhaps 32 individuals together with remains of Ursus deningeri and other carnivores and a biface nicknamed Excalibur.[64] It is hypothesized that this Acheulean axe made of red quartzite was some kind of ritual offering for a funeral. If it is so, it would be the oldest evidence of known of funerary practices.[64] Ninety percent of the known H. heidelbergensis remains have been obtained from this site. The fossil pit bones include:

- A complete cranium (skull 5), nicknamed Miguelón, and fragments of other crania, such as skull 4, nicknamed Agamemnón and skull 6, nicknamed Rui (from El Cid, a local hero).

- A complete pelvis (pelvis 1), nicknamed Elvis, in remembrance of Elvis Presley.

- Mandibles, teeth, and many postcranial bones (femurs, hand and foot bones, vertebrae, ribs, etc.)

Nearby sites contain the only known and controversial Homo antecessor fossils.

There is current debate among scholars whether the remains at Sima de los Huesos are those of H. heidelbergensis or early H. neanderthalensis.[65] In 2015, the study of mitochondrial DNA samples from three caves Sima de los Huesos revealed that they are "distantly related to the mitochondrial DNA of Denisovans rather than to that of Neanderthals."[66]

In 2016 Nuclear DNA analysis determined the Sima hominins are Neanderthals and not Denisova hominins and the divergence between Neanderthals and Denisovans predates 430,000 years ago.[67][68]

Suffolk, England

In 2005 flint tools and teeth from the water vole Mimomys savini, a key dating species, were found in the cliffs at Pakefield near Lowestoft in Suffolk. This suggests that hominins can be dated in England to 700,000 years ago, potentially a cross between H. antecessor and H. heidelbergensis.[69][70][71][72][73]

Schöningen, Germany

The Schöningen Spears are eight wooden throwing spears from the Palaeolithic Age, that were found under the management of Dr. Hartmut Thieme from the Lower Saxony State Service for Cultural Heritage (NLD) between 1994 and 1998 in the open-cast lignite mine, Schöningen, county Helmstedt, Germany, together with approx. 16,000 animal bones. More than 300,000 years old,[74][75][76][77] they are the oldest completely preserved hunting weapons in the world and they are regarded as the first evidence of the active hunt by H. heidelbergensis. These discoveries have permanently changed the picture of the cultural and social development of early man.[78][79]

See also

- Altamura man

- Homo cepranensis

- Homo rhodesiensis

- List of fossil sites (with link directory)

- List of human evolution fossils - hominina (hominin)

- Swanscombe Heritage Park

References

- ↑ "Homo heidelbergensis (600,000 to 100,000 years ago)- Species Description". WGBH Educational Foundation and Clear Blue Sky Productions, Inc. Retrieved November 29, 2015.

- ↑ "Homo heidelbergensis Online Biology Dictionary - EUGENE M. MCCARTHY, PHD". EUGENE M. MCCARTHY, PHD - macroevolution net. Retrieved November 29, 2015.

- ↑ "Archaeological Site of Atapuerca". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved November 29, 2015.

- ↑ "Homo heidelbergensis". Natural History Museum, London. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

- 1 2 "Homo heidelbergensis: Evolutionary Tree information". Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

- ↑ Mounier, Aurélien; Marchal, François; Condemi, Silvana (2009). "Is Homo heidelbergensis a distinct species? New insight on the Mauer mandible". Journal of Human Evolution. 56 (3): 219–46. PMID 19249816. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2008.12.006.

- ↑ "Prehistoric World Hominid Chronology by Peter Kessler Homo neanderthalis". Kessler Associates. July 26, 2005. Retrieved December 9, 2015.

- ↑ "What was Homo heidelbergensis? - DNA studies on both species indicate that the two were certainly distinct from each other, although related through their common Homo heidelbergensis ancestors.". InnovateUs Inc. Retrieved November 29, 2015.

- ↑ "Der Homo heidelbergensis - Vor etwa 700 000 Jahren taucht der Homo heidelbergensis in Afrika auf und wandert dann über eine noch unbekannte Route ebenfalls nach Europa aus...". Homo heidelbergensis von Mauer e.V. Retrieved November 29, 2015.

- ↑ Reid GB, Hetherington R (2010). The climate connection: climate change and modern human evolution. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 64. ISBN 0-521-14723-9.

- ↑ Meredith M (2011). Born in Africa: The Quest for the Origins of Human Life. New York: PublicAffairs. ISBN 1-58648-663-2.

- ↑ "Homo heidelbergensis - Comparison of Neanderthal and modern human DNA suggests that the two lineages diverged from a common ancestor, most likely Homo heidelbergensis". Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved October 29, 2015.

- ↑ "Denisovans, Neandertals, Archaics as Human Races - Anthropology can now confidently report that Neandertals, Denisovans, and others labelled archaic are in fact an interbreeding part of the modern human lineage. We are the same species.". Living Anthropologically. Retrieved October 29, 2015.

- ↑ "Homo heidelbergensis - In Europa wurde er zum Vorfahren des vor etwa 30 000 Jahren ausgestorbenen Neandertalers, während der afrikanische Homo heidelbergensis zum Vorfahren des modernen Menschen, Homo sapiens, wurde.". Homo heidelbergensis von Mauer e.V. Retrieved November 29, 2015.

- ↑ "Homo heidelbergensis - The evolutionary dividing line between Homo erectus and modern humans was not sharp.". Dennis O'Neil. Retrieved November 29, 2015.

- ↑ "Is Homo heidelbergensis a distinct species? New insight on the Mauer mandible". researchgate net. Retrieved November 29, 2015.

- ↑ "The evolution and development of cranial form" (PDF). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Department of Anthropology Harvard University. 99: 1134–1139. doi:10.1073/pnas.022440799. Retrieved December 9, 2015.

- ↑ "Homo heidelbergensis - Key physical features". Australian Museum. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ↑ Johanna Kontny u. a.: Reisetagebuch eines Fossils. In: Günther A. Wagner u. a., S. 44.

- ↑ "Homo heidelbergensis - Until the 1990s it was common to place these specimens either in H. erectus or into a broad category along with Neanderthals that was often called archaic H. sapiens.". britannica com. Retrieved November 29, 2015.

- ↑ "Homo heidelbergensis is supported as a valid taxon. - Validité du taxon Homo heidelbergensis Schoetensack, 1908" (PDF). UNIVERSITÉ DE LA MÉDITERRANÉE - FACULTE DE MÉDECINE DE MARSEILLE. October 28, 2009. Retrieved November 29, 2015.

- ↑ "Die Evolution des Menschen - Homo heidelbergensis". evolution-mensch de. Retrieved November 29, 2015.

- ↑ "Hierzu zählte noch im Jahr 2010 auch das Geologisch-Paläontologische Institut der Universität Heidelberg, das den Unterkiefer seit 1908 verwahrt und ihn als Homo erectus heidelbergensis auswies. Inzwischen wird er jedoch auch in Heidelberg als Homo heidelbergensis bezeichnet, siehe". Sammlung des Instituts für Geowissenschaften. Retrieved November 29, 2015.

- ↑ "Homo heidelbergensis essay". Institute of Human Origins. Retrieved December 9, 2015.

- ↑ "Die Evolution des Menschen - Homo heidelbergensis - Die Tatsache, dass es keine klaren Übergänge zu geben scheint, macht es schwierig, eine Liste eindeutiger Merkmale des Homo heidelbergensis aufzustellen...". evolution-mensch de. Retrieved November 29, 2015.

- ↑ "Evolution of Modern Humans: Homo heidelbergensis". Behavioral Sciences Department, Palomar College. Retrieved 2012-12-01.

- ↑ "Homo heidelbergensis was only slightly taller than the Neanderthal". American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS). June 6, 2012. Retrieved November 29, 2015.

- ↑ Carretero, José-Miguel; Rodríguez, Laura; García-González, Rebeca; Arsuaga, Juan-Luis; Gómez-Olivencia, Asier; Lorenzo, Carlos; Bonmatí, Alejandro; Gracia, Ana; Martínez, Ignacio (2012). "Stature estimation from complete long bones in the Middle Pleistocene humans from the Sima de los Huesos, Sierra de Atapuerca (Spain)". Journal of Human Evolution. 62 (2): 242–55. PMID 22196156. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2011.11.004. Lay summary – ScienceDaily (June 6, 2012).

- ↑ Burger, Lee (November 2007). "Our Story: Human Ancestor Fossils". The Naked Scientists.

- 1 2 "Homo heidelbergensis essay". Institute of Human Origins. Retrieved October 29, 2015.

- ↑ "Scientists Determine Height of Homo Heidelbergensis". Sci-News. June 6, 2012. Retrieved November 29, 2015.

- ↑ "100 years of Homo heidelbergensis – life and times of a controversial taxon" (PDF). Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. Retrieved December 9, 2015.

- ↑ "Homo heidelbergensis - Eudald Carboneli et al. reported in the March 27, 2008 issue of Nature that a human jaw with a tooth dating 1.2-1.1 million years ago has been found in Sima del Elefante cave in the Atapuerca Mountains of Northern Spain.". palomar.edu. Retrieved October 29, 2015.

- ↑ The Mystery of the Pit of Bones, Atapuerca, Spain: Species Homo heidelbergensis. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved December 15, 2011.

- 1 2 Mithen, Steven (2006). The Singing Neanderthals, ISBN 978-0-674-02192-1

- ↑ Martínez I, Rosa M, Arsuaga JL, Jarabo P, Quam R, Lorenzo C, Gracia A, Carretero JM, Bermúdez de Castro JM (2004). "Auditory capacities in Middle Pleistocene humans from the Sierra de Atapuerca in Spain". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 101 (27): 9976–81. Bibcode:2004PNAS..101.9976M. JSTOR 3372572. PMC 454200

. PMID 15213327. doi:10.1073/pnas.0403595101.

. PMID 15213327. doi:10.1073/pnas.0403595101. - ↑ Lozano, Marina; Mosquera, Marina; De Castro, José María Bermúdez; Arsuaga, Juan Luis; Carbonell, Eudald (2009). "Right handedness of Homo heidelbergensis from Sima de los Huesos (Atapuerca, Spain) 500,000 years ago". Evolution and Human Behavior. 30 (5): 369–76. doi:10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2009.03.001.

- ↑ Schiller, Jon (2010). Human Evolution: Neanderthals & Homosapiens. CreateSpace.

- 1 2 Wilkins, Jayne; Schoville, Benjamin J.; Brown, Kyle S.; Chazan, Michael (2012). "Evidence for Early Hafted Hunting Technology". Science. 338 (6109): 942–6. Bibcode:2012Sci...338..942W. PMID 23161998. doi:10.1126/science.1227608. Lay summary – The Guardian (November 15, 2012).

- ↑ "Homo heidelbergensis Oldest Wooden Spear". Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved October 29, 2015.

- ↑ "A Heidelberg man of African origin". BIOPRO Baden-Württemberg. Retrieved November 30, 2015.

- ↑ "Homo heidelbergensis - Homo heidelbergensis began to develop regional differences that eventually gave rise to two species of humans". Australian Museum. Retrieved October 29, 2015.

- ↑ "Human Evolution in the Middle Pleistocene: The Role of Homo heidelbergensis by G. Philip Rightmire" (PDF). Instytut Archeologii Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego. Retrieved November 30, 2015.

- ↑ Buck, Laura T.; Stringer, Chris B. (2014). "What is H. heidelbergensis' position in the human family tree?". Current Biology. ScienceDirect. 24 (6): R214–R215. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2013.12.048. Retrieved October 29, 2015.

- ↑ "Human Evolution: Neanderthals & Homosapiens [sic] by Jon Schiller". Google Books. Retrieved October 29, 2015.

- ↑ Stringer, Chris (2012). "Comment: What makes a modern human.". Nature. 485 (7396): 33–35 [34]. PMID 22552077. doi:10.1038/485033a.

- ↑ Hierzu zählte noch im Jahr 2010 auch das Geologisch-Paläontologische Institut der Universität Heidelberg, das den Unterkiefer seit 1908 verwahrt und ihn als Homo erectus heidelbergensis auswies. Inzwischen wird er jedoch auch in Heidelberg als Homo heidelbergensis bezeichnet, siehe Sammlung des Instituts für Geowissenschaften

- ↑ "DNA from Neandertal relative may shake up human family tree". American Association for the Advancement of Science. September 11, 2015. Retrieved November 29, 2015.

- ↑ "Researchers Sequenced 430,000-Year-Old DNA From Neanderthal Relative". IFLScience. September 13, 2015. Retrieved November 29, 2015.

- ↑ "Human Evolution in the Middle Pleistocene: The Role of Homo heidelbergensis by G. Philip Rightmire" (PDF). Instytut Archeologii UW. Retrieved October 29, 2015.

- ↑ "Hominin DNA baffles experts - Another ancient genome, another mystery. DNA gleaned from a 400,000-year-old femur from Spain has revealed an unexpected link between Europe’s hominin inhabitants of the time and a cryptic population, the Denisovans...". Nature Publishing Group. Retrieved October 29, 2015.

- ↑ "World History Encyclopedia, Volume 10 By Alfred J. Andrea, Kevin McGeough, William E. Mierse, Mark Aldenderfer, Carolyn Neel". Google Books. Retrieved October 29, 2015.

- ↑ Otto Schoetensack: Der Unterkiefer des Homo heidelbergensis aus den Sanden von Mauer bei Heidelberg. Ein Beitrag zur Paläontologie des Menschen. Leipzig, 1908, Verlag von Wilhelm Engelmann

- ↑ Cartmill, Matt; Smith, Fred H. (2009). The Human Lineage. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0471214914. Retrieved 2013-03-01.

- ↑ "Kabwe 1". The Smithsonian Institution's Human Origin Program. Retrieved 2 November 2010.

- ↑ Begun, David R., ed. (2012). "The African Origin of Homo sapiens". A Companion to Paleoanthropology. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781118332375.

- ↑ Singer, R (September 1954). "The saldanha skull from hopefield, South Africa". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 12 (3): 345–362. PMID 13207329. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330120309. Retrieved November 29, 2015.

- ↑ "Petralona 1". Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved November 29, 2015.

- ↑ "Tautavel Man". Saissac. Retrieved November 29, 2015.

- ↑ "Bodo Skull and Jaw". Skulls Unlimited. Retrieved 15 October 2012.

- ↑ "Bodo". Humanorigins.si.edu. Retrieved 15 October 2012.

- ↑ Streeter et al. 2001, Margret (2001). "Histomorphometric age assessment of the Boxgrove 1 tibial diaphysis". Journal of Human Evolution. 40 (4): 331–338. PMID 11312585. doi:10.1006/jhev.2001.0460. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- ↑ A History of Britain, Richard Dargie (2007), p. 8–9

- 1 2 "BBC - Science & Nature - The evolution of man".

- ↑ "Sorry, that's a dead link - Natural History Museum".

- ↑ "Nuclear DNA sequences from the hominin remains of Sima de los Huesos, Atapuerca, Spain // 5TH ANNUAL MEETING OF THE European Society for the study of Human Evolution, 10 – 12 SEPTEMBER 2015 LONDON/UK: Nuclear DNA sequences from the hominin" (PDF).

- ↑ magazine, Ewen Callaway, Nature. "Oldest Ancient-Human DNA Details Dawn of Neandertals". Scientific American. Retrieved 2016-03-14.

- ↑ Meyer, Matthias; Arsuaga, Juan-Luis; de Filippo, Cesare; Nagel, Sarah; Aximu-Petri, Ayinuer; Nickel, Birgit; Martínez, Ignacio; Gracia, Ana; de Castro, José María Bermúdez (2016-03-14). "Nuclear DNA sequences from the Middle Pleistocene Sima de los Huesos hominins". Nature. 531 (7595): 504–507. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 26976447. doi:10.1038/nature17405.

- ↑ Parfitt, Simon A.; Barendregt, René W.; Breda, Marzia; Candy, Ian; Collins, Matthew J.; Coope, G. Russell; Durbidge, Paul; Field, Mike H.; Lee, Jonathan R. (2005). "The earliest record of human activity in northern Europe". Nature. 438 (7070): 1008–12. Bibcode:2005Natur.438.1008P. PMID 16355223. doi:10.1038/nature04227.

- ↑ Roebroeks, Wil (2005). "Archaeology: Life on the Costa del Cromer". Nature. 438 (7070): 921–2. Bibcode:2005Natur.438..921R. PMID 16355198. doi:10.1038/438921a.

- ↑ Parfitt, Simon; Stuart, Tony; Stringer, Chris; Preece, Richard (January–February 2006). "700,000 years old: found in Suffolk". British Archaeology. 86.

- ↑ Good, Clare; Plouviez, Jude (2007). The Archaeology of the Suffolk Coast (PDF). Suffolk County Council Archaeological Service.

- ↑ Kinver, Mark (14 December 2005). "Tools unlock secrets of early man". BBC News. Retrieved November 16, 2012.

- ↑ Hartmut Thieme, Reinhard Maier (Hrsg.): Archäologische Ausgrabungen im Braunkohlentagebau Schöningen. Landkreis Helmstedt, Hannover 1995.

- ↑ Hartmut Thieme: Die ältesten Speere der Welt – Fundplätze der frühen Altsteinzeit im Tagebau Schöningen. In: Archäologisches Nachrichtenblatt 10, 2005, S. 409-417.

- ↑ Michael Baales, Olaf Jöris: Zur Altersstellung der Schöninger Speere. In: J. Burdukiewicz u. a. (Hrsg.): Erkenntnisjäger. Kultur und Umwelt des frühen Menschen. Veröffentlichungen des Landesamtes für Archäologie Sachsen-Anhalt 57, 2003 (Festschrift Dietrich Mania), S. 281-288.

- ↑ O. Jöris: Aus einer anderen Welt – Europa zur Zeit des Neandertalers. In: N. J. Conard u. a. (Hrsg.): Vom Neandertaler zum modernen Menschen. Ausstellungskatalog Blaubeuren 2005, S. 47-70.

- ↑ Thieme H. 2007. Der große Wurf von Schöningen: Das neue Bild zur Kultur des frühen Menschen in: Thieme H. (ed.) 2007: Die Schöninger Speere – Mensch und Jagd vor 400 000 Jahren. S. 224-228 Konrad Theiss Verlag, Stuttgart ISBN 3-89646-040-4

- ↑ Haidle M.N. 2006: Menschenaffen? Affenmenschen? Mensch! Kognition und Sprache im Altpaläolithikum. In Conard N.J. (ed.): Woher kommt der Mensch. S. 69-97. Attempto Verlag. Tübingen ISBN 3-89308-381-2

Further reading

- Sauer, A. (1985). Erläuterungen zur Geol. Karte 1 : 25 000 Baden-Württ. Stuttgart.

- Schoetensack, O. (1908). Der Unterkiefer des Homo heidelbergensis aus den Sanden von Mauer bei Heidelberg. Leipzig: Wilhelm Engelmann.

- Weinert, Hans (1937). "Dem Unterkiefer von Mauer zur 30jährigen Wiederkehr seiner Entdeckung". Zeitschrift für Morphologie und Anthropologie (in German). 37 (1): 102–13. JSTOR 25749563.

- Rice, Stanley (2006). Encyclopedia of Evolution. Facts on File, Inc.

- Back ache: it’s been a pain for millions of years - University of Cambridge

- Studies on the condition and structure of bone of the Saldanha fossil cranium

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Homo heidelbergensis. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1920 Encyclopedia Americana article Heidelberg Man. |

- Homo heidelbergensis – The Smithsonian Institution's Human Origins Program

- Theme park: The Grafenrain sand mine

- homepage of Mauer 1 Club

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre - Archaeological Site of Atapuerca

- Human Timeline (Interactive) – Smithsonian, National Museum of Natural History (August 2016).