Human evolution

Human evolution, also known as hominization, is the evolutionary process that led to the emergence of anatomically modern humans, beginning with the evolutionary history of primates – in particular genus Homo – and leading to the emergence of Homo sapiens as a distinct species of the hominid family, the great apes. This process involved the gradual development of traits such as human bipedalism and language.[1]

The study of human evolution involves many scientific disciplines, including physical anthropology, primatology, archaeology, paleontology, neurobiology, ethology, linguistics, evolutionary psychology, embryology and genetics.[2] Genetic studies show that primates diverged from other mammals about 85 million years ago, in the Late Cretaceous period, and the earliest fossils appear in the Paleocene, around 55 million years ago.[3]

Within the Hominoidea (apes) superfamily, the Hominidae family diverged from the Hylobatidae (gibbon) family some 15–20 million years ago; African great apes (subfamily Homininae) diverged from orangutans (Ponginae) about 14 million years ago; the Hominini tribe (humans, Australopithecines and other extinct biped genera, and chimpanzee) parted from the Gorillini tribe (gorillas) between 9 million years ago and 8 million years ago; and, in turn, the subtribes Hominina (humans and biped ancestors) and Panina (chimps) separated about 7.5 million years ago to 5.6 million years ago.[4]

Anatomical changes

Human evolution from its first separation from the last common ancestor of humans and chimpanzees is characterized by a number of morphological, developmental, physiological, and behavioral changes. The most significant of these adaptations are bipedalism, increased brain size, lengthened ontogeny (gestation and infancy), and decreased sexual dimorphism. The relationship between these changes is the subject of ongoing debate.[5] Other significant morphological changes included the evolution of a power and precision grip, a change first occurring in H. erectus.[6]

Bipedalism

Bipedalism is the basic adaptation of the hominid and is considered the main cause behind a suite of skeletal changes shared by all bipedal hominids. The earliest hominin, of presumably primitive bipedalism, is considered to be either Sahelanthropus[7] or Orrorin, both of which arose some 6 to 7 million years ago. The non-bipedal knuckle-walkers, the gorilla and chimpanzee, diverged from the hominin line over a period covering the same time, so either of Sahelanthropus or Orrorin may be our last shared ancestor. Ardipithecus, a full biped, arose somewhat later.

The early bipeds eventually evolved into the australopithecines and still later into the genus Homo. There are several theories of the adaptation value of bipedalism. It is possible that bipedalism was favored because it freed the hands for reaching and carrying food, saved energy during locomotion,[8] enabled long distance running and hunting, provided an enhanced field of vision, and helped avoid hyperthermia by reducing the surface area exposed to direct sun; features all advantageous for thriving in the new savanna and woodland environment created as a result of the East African Rift Valley uplift versus the previous closed forest habitat.[9][8][10] A new study provides support for the hypothesis that walking on two legs, or bipedalism, evolved because it used less energy than quadrupedal knuckle-walking.[11][12] However, recent studies suggest that bipedality without the ability to use fire would not have allowed global dispersal.[13] This change in gait saw a lengthening of the legs proportionately when compared to the length of the arms, which were shortened through the removal of the need for brachiation. Another change is the shape of the big toe. Recent studies suggest that Australopithecines still lived part of the time in trees as a result of maintaining a grasping big toe. This was progressively lost in Habilines.

Anatomically, the evolution of bipedalism has been accompanied by a large number of skeletal changes, not just to the legs and pelvis, but also to the vertebral column, feet and ankles, and skull.[14] The femur evolved into a slightly more angular position to move the center of gravity toward the geometric center of the body. The knee and ankle joints became increasingly robust to better support increased weight. To support the increased weight on each vertebra in the upright position, the human vertebral column became S-shaped and the lumbar vertebrae became shorter and wider. In the feet the big toe moved into alignment with the other toes to help in forward locomotion. The arms and forearms shortened relative to the legs making it easier to run. The foramen magnum migrated under the skull and more anterior.[15]

The most significant changes occurred in the pelvic region, where the long downward facing iliac blade was shortened and widened as a requirement for keeping the center of gravity stable while walking;[16] bipedal hominids have a shorter but broader, bowl-like pelvis due to this. A drawback is that the birth canal of bipedal apes is smaller than in knuckle-walking apes, though there has been a widening of it in comparison to that of australopithecine and modern humans, permitting the passage of newborns due to the increase in cranial size but this is limited to the upper portion, since further increase can hinder normal bipedal movement.[17]

The shortening of the pelvis and smaller birth canal evolved as a requirement for bipedalism and had significant effects on the process of human birth which is much more difficult in modern humans than in other primates. During human birth, because of the variation in size of the pelvic region, the fetal head must be in a transverse position (compared to the mother) during entry into the birth canal and rotate about 90 degrees upon exit.[18] The smaller birth canal became a limiting factor to brain size increases in early humans and prompted a shorter gestation period leading to the relative immaturity of human offspring, who are unable to walk much before 12 months and have greater neoteny, compared to other primates, who are mobile at a much earlier age.[10] The increased brain growth after birth and the increased dependency of children on mothers had a big effect upon the female reproductive cycle,[19] and the more frequent appearance of alloparenting in humans when compared with other hominids.[20] Delayed human sexual maturity also led to the evolution of menopause with one explanation providing that elderly women could better pass on their genes by taking care of their daughter's offspring, as compared to having more children of their own.[21]

Encephalization

The human species eventually developed a much larger brain than that of other primates—typically 1,330 cm3 in modern humans, nearly three times the size of that of a chimpanzee or gorilla.[22] The pattern of encephalization started with Homo habilis, after a hiatus with Australopithecus anamensis and Ardipithecus species which had smaller brains as a result of their bipedal locomotion[23] which at approximately 600 cm3 Homo habilis had a brain slightly larger than that of chimpanzees, and this evolution continued with Homo erectus (800–1,100 cm3), reaching a maximum in Neanderthals with an average size of (1,200–1,900 cm3), larger even than modern Homo sapiens. This pattern of brain increase happened through the pattern of human postnatal brain growth which differs from that of other apes (heterochrony). It also allows for extended periods of social learning and language acquisition in juvenile humans which may have begun 2 million years ago. However, the differences between the structure of human brains and those of other apes may be even more significant than differences in size.[24][25][26][27]

The increase in volume over time has affected areas within the brain unequally—the temporal lobes, which contain centers for language processing, have increased disproportionately, and seems to favor a belief that there was evolution after leaving Africa, as has the prefrontal cortex which has been related to complex decision-making and moderating social behavior.[22] Encephalization has been tied to an increasing emphasis on meat in the diet,[28][29][30] or with the development of cooking,[31] and it has been proposed that intelligence increased as a response to an increased necessity for solving social problems as human society became more complex.[32] The human brain was able to expand because of the changes in the morphology of smaller mandibles and mandible muscle attachments to the skull into allowing more room for the brain to grow.[33]

The increase in volume of the neocortex also included a rapid increase in size of the cerebellum. Traditionally the cerebellum has been associated with a paleocerebellum and archicerebellum as well as a neocerebellum. Its function has also traditionally been associated with balance, fine motor control but more recently speech and cognition. The great apes including humans and its antecessors had a more pronounced development of the cerebellum relative to the neocortex than other primates. It has been suggested that because of its function of sensory-motor control and assisting in learning complex muscular action sequences, the cerebellum may have underpinned the evolution of human's technological adaptations including the preadaptation of speech.[34][35][36][37]

The reason for this encephalization is difficult to discern, as the major changes from Homo erectus to Homo heidelbergensis were not associated with major changes in technology. It has been suggested that the changes have been associated with social changes, increased empathic abilities[38][39] and increases in size of social groupings[40][41][42]

Sexual dimorphism

The reduced degree of sexual dimorphism is visible primarily in the reduction of the male canine tooth relative to other ape species (except gibbons) and reduced brow ridges and general robustness of males. Another important physiological change related to sexuality in humans was the evolution of hidden estrus. Humans and bonobos are the only apes in which the female is fertile year round and in which no special signals of fertility are produced by the body (such as genital swelling during estrus).

Nonetheless, humans retain a degree of sexual dimorphism in the distribution of body hair and subcutaneous fat, and in the overall size, males being around 15% larger than females. These changes taken together have been interpreted as a result of an increased emphasis on pair bonding as a possible solution to the requirement for increased parental investment due to the prolonged infancy of offspring.

Ulnar opposition

The ulnar opposition – the contact between the thumb and the tip of the little finger of the same hand – is unique to anatomically modern humans.[43][44] In other primates the thumb is short and unable to touch the little finger.[43] The ulnar opposition facilitates the precision grip and power grip of the human hand, underlying all the skilled manipulations.

Other changes

A number of other changes have also characterized the evolution of humans, among them an increased importance on vision rather than smell; a smaller gut; loss of body hair; evolution of sweat glands; a change in the shape of the dental arcade from being u-shaped to being parabolic; development of a chin (found in Homo sapiens alone); development of styloid processes; and the development of a descended larynx.

History of study

Orange labels: known ice ages.

Also see: Human timeline and Nature timeline

Before Darwin

The word homo, the name of the biological genus to which humans belong, is Latin for "human". It was chosen originally by Carl Linnaeus in his classification system. The word "human" is from the Latin humanus, the adjectival form of homo. The Latin "homo" derives from the Indo-European root *dhghem, or "earth".[45] Linnaeus and other scientists of his time also considered the great apes to be the closest relatives of humans based on morphological and anatomical similarities.

Darwin

The possibility of linking humans with earlier apes by descent became clear only after 1859 with the publication of Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species, in which he argued for the idea of the evolution of new species from earlier ones. Darwin's book did not address the question of human evolution, saying only that "Light will be thrown on the origin of man and his history."[46]

The first debates about the nature of human evolution arose between Thomas Henry Huxley and Richard Owen. Huxley argued for human evolution from apes by illustrating many of the similarities and differences between humans and apes, and did so particularly in his 1863 book Evidence as to Man's Place in Nature. However, many of Darwin's early supporters (such as Alfred Russel Wallace and Charles Lyell) did not initially agree that the origin of the mental capacities and the moral sensibilities of humans could be explained by natural selection, though this later changed. Darwin applied the theory of evolution and sexual selection to humans when he published The Descent of Man in 1871.[47]

First fossils

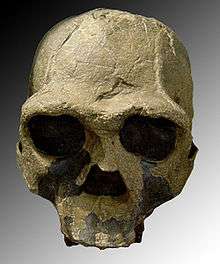

A major problem at that time was the lack of fossil intermediaries. Neanderthal remains were discovered in a limestone quarry in 1856, three years before the publication of On the Origin of Species, and Neanderthal fossils had been discovered in Gibraltar even earlier, but it was originally claimed that these were human remains of a creature suffering some kind of illness.[48] Despite the 1891 discovery by Eugène Dubois of what is now called Homo erectus at Trinil, Java, it was only in the 1920s when such fossils were discovered in Africa, that intermediate species began to accumulate. In 1925, Raymond Dart described Australopithecus africanus.[49] The type specimen was the Taung Child, an australopithecine infant which was discovered in a cave. The child's remains were a remarkably well-preserved tiny skull and an endocast of the brain.

Although the brain was small (410 cm3), its shape was rounded, unlike that of chimpanzees and gorillas, and more like a modern human brain. Also, the specimen showed short canine teeth, and the position of the foramen magnum (the hole in the skull where the spine enters) was evidence of bipedal locomotion. All of these traits convinced Dart that the Taung Child was a bipedal human ancestor, a transitional form between apes and humans.

The East African fossils—and Homo naledi in South Africa

During the 1960s and 1970s, hundreds of fossils were found in East Africa in the regions of the Olduvai Gorge and Lake Turkana. The driving force of these searches was the Leakey family, with Louis Leakey and his wife Mary Leakey, and later their son Richard and daughter-in-law Meave—all successful and world-renowned fossil hunters and paleoanthropologists. From the fossil beds of Olduvai and Lake Turkana they amassed specimens of the early hominins: the australopithecines and Homo species, and even Homo erectus.

These finds cemented Africa as the cradle of humankind. In the late 1970s and the 1980s, Ethiopia emerged as the new hot spot of paleoanthropology after "Lucy", the most complete fossil member of the species Australopithecus afarensis, was found in 1974 by Donald Johanson near Hadar in the desertic Afar Triangle region of northern Ethiopia. Although the specimen had a small brain, the pelvis and leg bones were almost identical in function to those of modern humans, showing with certainty that these hominins had walked erect.[50] Lucy was classified as a new species, Australopithecus afarensis, which is thought to be more closely related to the genus Homo as a direct ancestor, or as a close relative of an unknown ancestor, than any other known hominid or hominin from this early time range; see terms "hominid" and "hominin".[51] (The specimen was nicknamed "Lucy" after the Beatles' song "Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds", which was played loudly and repeatedly in the camp during the excavations.[52]) The Afar Triangle area would later yield discovery of many more hominin fossils, particularly those uncovered or described by teams headed by Tim D. White in the 1990s, including Ardipithecus ramidus and Ardipithecus kadabba.[53]

In 2013, fossil skeletons of Homo naledi, an extinct species of hominin assigned (provisionally) to the genus Homo, were found in the Rising Star Cave system, a site in South Africa's Cradle of Humankind region in Gauteng province near Johannesburg.[54][55] As of September 2015, fossils of at least fifteen individuals, amounting to 1550 specimens, have been excavated from the cave.[55] The species is characterized by a body mass and stature similar to small-bodied human populations, a smaller endocranial volume similar to Australopithecus, and a cranial morphology (skull shape) similar to early Homo species. The skeletal anatomy combines primitive features known from australopithecines with features known from early hominins. The individuals show signs of having been deliberately disposed of within the cave near the time of death. The fossils have not yet been dated.[56]

The genetic revolution

The genetic revolution in studies of human evolution started when Vincent Sarich and Allan Wilson measured the strength of immunological cross-reactions of blood serum albumin between pairs of creatures, including humans and African apes (chimpanzees and gorillas).[57] The strength of the reaction could be expressed numerically as an immunological distance, which was in turn proportional to the number of amino acid differences between homologous proteins in different species. By constructing a calibration curve of the ID of species' pairs with known divergence times in the fossil record, the data could be used as a molecular clock to estimate the times of divergence of pairs with poorer or unknown fossil records.

In their seminal 1967 paper in Science, Sarich and Wilson estimated the divergence time of humans and apes as four to five million years ago,[57] at a time when standard interpretations of the fossil record gave this divergence as at least 10 to as much as 30 million years. Subsequent fossil discoveries, notably "Lucy", and reinterpretation of older fossil materials, notably Ramapithecus, showed the younger estimates to be correct and validated the albumin method.

Progress in DNA sequencing, specifically mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) and then Y-chromosome DNA (Y-DNA) advanced the understanding of human origins.[58][9][59] Application of the molecular clock principle revolutionized the study of molecular evolution.

On the basis of a separation from the orangutan between 10 and 20 million years ago, earlier studies of the molecular clock suggested that there were about 76 mutations per generation that were not inherited by human children from their parents; this evidence supported the divergence time between hominins and chimps noted above. However, a 2012 study in Iceland of 78 children and their parents suggests a mutation rate of only 36 mutations per generation; this datum extends the separation between humans and chimps to an earlier period greater than 7 million years ago (Ma). Additional research with 226 offspring of wild chimp populations in 8 locations suggests that chimps reproduce at age 26.5 years, on average; which suggests the human divergence from chimps occurred between 7 and 13 million years ago. And these data suggest that Ardipithecus (4.5 Ma), Orrorin (6 Ma) and Sahelanthropus (7 Ma) all may be on the hominid lineage, and even that the separation may have occurred outside the East African Rift region.

Furthermore, analysis of the two species' genes in 2006 provides evidence that after human ancestors had started to diverge from chimpanzees, interspecies mating between "proto-human" and "proto-chimps" nonetheless occurred regularly enough to change certain genes in the new gene pool:

- A new comparison of the human and chimp genomes suggests that after the two lineages separated, they may have begun interbreeding... A principal finding is that the X chromosomes of humans and chimps appear to have diverged about 1.2 million years more recently than the other chromosomes.

The research suggests:

- There were in fact two splits between the human and chimp lineages, with the first being followed by interbreeding between the two populations and then a second split. The suggestion of a hybridization has startled paleoanthropologists, who nonetheless are treating the new genetic data seriously.[60]

The quest for the earliest hominin

In the 1990s, several teams of paleoanthropologists were working throughout Africa looking for evidence of the earliest divergence of the hominin lineage from the great apes. In 1994, Meave Leakey discovered Australopithecus anamensis. The find was overshadowed by Tim D. White's 1995 discovery of Ardipithecus ramidus, which pushed back the fossil record to 4.2 million years ago.

In 2000, Martin Pickford and Brigitte Senut discovered, in the Tugen Hills of Kenya, a 6-million-year-old bipedal hominin which they named Orrorin tugenensis. And in 2001, a team led by Michel Brunet discovered the skull of Sahelanthropus tchadensis which was dated as 7.2 million years ago, and which Brunet argued was a bipedal, and therefore a hominid—that is, a hominin (cf Hominidae; terms "hominids" and hominins).

Human dispersal

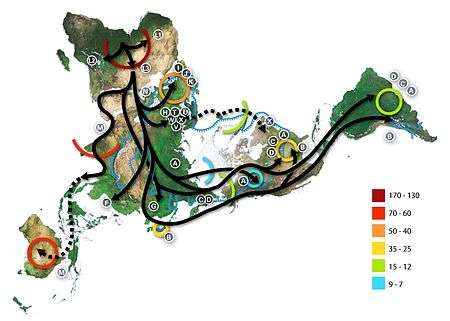

Anthropologists in the 1980s were divided regarding some details of reproductive barriers and migratory dispersals of the Homo genus. Subsequently, genetics has been used to investigate and resolve these issues. According to the Sahara pump theory evidence suggests that genus Homo have migrated out of Africa at least three and possibly four times (e.g. Homo erectus, Homo heidelbergensis and two or three times for Homo sapiens). Recent evidence suggests these dispersals are closely related to fluctuating periods of climate change.[63]

Recent evidence suggests that humans may have left Africa half a million years earlier than previously thought. A joint Franco-Indian team has found human artefacts in the Siwalk Hills north of New Delhi dating back at least 2.6 million years. This is earlier than the previous earliest finding of genus Homo at Dmanisi, in Georgia, dating to 1.85 million years. Although controversial, tools found at a Chinese cave strengthen the case that humans used tools as far back as 2.48 million years ago.[64] This suggests that the Asian "Chopper" tool tradition, found in Java and northern China may have left Africa before the appearance of the Acheulian hand axe.

Dispersal of modern Homo sapiens

Up until the genetic evidence became available there were two dominant models for the dispersal of modern humans. The multiregional hypothesis proposed that Homo genus contained only a single interconnected population as it does today (not separate species), and that its evolution took place worldwide continuously over the last couple million years. This model was proposed in 1988 by Milford H. Wolpoff.[65][66] In contrast the "out of Africa" model proposed that modern H. sapiens speciated in Africa recently (that is, approximately 200,000 years ago) and the subsequent migration through Eurasia resulted in nearly complete replacement of other Homo species. This model has been developed by Chris B. Stringer and Peter Andrews.[67][68]

Sequencing mtDNA and Y-DNA sampled from a wide range of indigenous populations revealed ancestral information relating to both male and female genetic heritage, and strengthened the Out of Africa theory and weakened the views of Multiregional Evolutionism.[69] Aligned in genetic tree differences were interpreted as supportive of a recent single origin.[70] Analyses have shown a greater diversity of DNA patterns throughout Africa, consistent with the idea that Africa is the ancestral home of mitochondrial Eve and Y-chromosomal Adam, and that modern human dispersal out of Africa has only occurred over the last 55,000 years.[71]

"Out of Africa" has thus gained much support from research using female mitochondrial DNA and the male Y chromosome. After analysing genealogy trees constructed using 133 types of mtDNA, researchers concluded that all were descended from a female African progenitor, dubbed Mitochondrial Eve. "Out of Africa" is also supported by the fact that mitochondrial genetic diversity is highest among African populations.[72]

A broad study of African genetic diversity, headed by Sarah Tishkoff, found the San people had the greatest genetic diversity among the 113 distinct populations sampled, making them one of 14 "ancestral population clusters". The research also located a possible origin of modern human migration in south-western Africa, near the coastal border of Namibia and Angola.[73] The fossil evidence was insufficient for archaeologist Richard Leakey to resolve the debate about exactly where in Africa modern humans first appeared.[74] Studies of haplogroups in Y-chromosomal DNA and mitochondrial DNA have largely supported a recent African origin.[75] All the evidence from autosomal DNA also predominantly supports a Recent African origin. However, evidence for archaic admixture in modern humans, both in Africa and later, throughout Eurasia has recently been suggested by a number of studies.[76]

Recent sequencing of Neanderthal[77] and Denisovan[78] genomes shows that some admixture with these populations has occurred. Modern humans outside Africa have 2–4% Neanderthal alleles in their genome, and some Melanesians have an additional 4–6% of Denisovan alleles. These new results do not contradict the "out of Africa" model, except in its strictest interpretation, although they make the situation more complex. After recovery from a genetic bottleneck that could possibly be due to the Toba supervolcano catastrophe, a fairly small group left Africa and later briefly interbred on three separate occasions with Neanderthals, probably in the middle-east, on the Eurasian steppe or even in North Africa before their departure. Their still predominantly African descendants spread to populate the world. A fraction in turn interbred with Denisovans, probably in south-east Asia, before populating Melanesia.[79] HLA haplotypes of Neanderthal and Denisova origin have been identified in modern Eurasian and Oceanian populations.[80] The Denisovan EPAS1 gene has also been found in Tibetan populations.[81]

There are still differing theories on whether there was a single exodus from Africa or several. A multiple dispersal model involves the Southern Dispersal theory,[82] which has gained support in recent years from genetic, linguistic and archaeological evidence. In this theory, there was a coastal dispersal of modern humans from the Horn of Africa crossing the Bab el Mandib to Yemen at a lower sea level around 70,000 years ago. This group helped to populate Southeast Asia and Oceania, explaining the discovery of early human sites in these areas much earlier than those in the Levant.[82] This group seems to have been dependent upon marine resources for their survival.

Stephen Oppenheimer has proposed a second wave of humans may have later dispersed through the Persian Gulf oases, and the Zagros mountains into the Middle East. Alternatively it may have come across the Sinai Peninsula into Asia, from shortly after 50,000 yrs BP, resulting in the bulk of the human populations of Eurasia. It has been suggested that this second group possibly possessed a more sophisticated "big game hunting" tool technology and was less dependent on coastal food sources than the original group. Much of the evidence for the first group's expansion would have been destroyed by the rising sea levels at the end of each glacial maximum.[82] The multiple dispersal model is contradicted by studies indicating that the populations of Eurasia and the populations of Southeast Asia and Oceania are all descended from the same mitochondrial DNA L3 lineages, which support a single migration out of Africa that gave rise to all non-African populations.[83]

Stephen Oppenheimer, on the basis of the early date of Badoshan Iranian Aurignacian, suggests that this second dispersal, may have occurred with a pluvial period about 50,000 years before the present, with modern human big-game hunting cultures spreading up the Zagros Mountains, carrying modern human genomes from Oman, throughout the Persian Gulf, northward into Armenia and Anatolia, with a variant travelling south into Israel and to Cyrenicia.[84]

Evidence

The evidence on which scientific accounts of human evolution are based comes from many fields of natural science. The main source of knowledge about the evolutionary process has traditionally been the fossil record, but since the development of genetics beginning in the 1970s, DNA analysis has come to occupy a place of comparable importance. The studies of ontogeny, phylogeny and especially evolutionary developmental biology of both vertebrates and invertebrates offer considerable insight into the evolution of all life, including how humans evolved. The specific study of the origin and life of humans is anthropology, particularly paleoanthropology which focuses on the study of human prehistory.[85]

Evidence from molecular biology

The closest living relatives of humans are bonobos and chimpanzees (both genus Pan) and gorillas (genus Gorilla).[86] With the sequencing of both the human and chimpanzee genome, current estimates of the similarity between their DNA sequences range between 95% and 99%.[86][87][88] By using the technique called the molecular clock which estimates the time required for the number of divergent mutations to accumulate between two lineages, the approximate date for the split between lineages can be calculated.

The gibbons (family Hylobatidae) and then orangutans (genus Pongo) were the first groups to split from the line leading to the hominins, including humans—followed by gorillas, and, ultimately, by the chimpanzees (genus Pan). The splitting date between hominin and chimpanzee lineages is placed by some between 4 to 8 million years ago, that is, during the Late Miocene.[4][89][90] Speciation, however, appears to have been unusually drawn-out. Initial divergence occurred sometime between 7 to 13 million years ago, but ongoing hybridization blurred the separation and delayed complete separation during several millions of years. Patterson (2006) dated the final divergence at 5 to 6 million years ago.[91]

Genetic evidence has also been employed to resolve the question of whether there was any gene flow between early modern humans and Neanderthals, and to enhance our understanding of the early human migration patterns and splitting dates. By comparing the parts of the genome that are not under natural selection and which therefore accumulate mutations at a fairly steady rate, it is possible to reconstruct a genetic tree incorporating the entire human species since the last shared ancestor.

Each time a certain mutation (single-nucleotide polymorphism) appears in an individual and is passed on to his or her descendants a haplogroup is formed including all of the descendants of the individual who will also carry that mutation. By comparing mitochondrial DNA which is inherited only from the mother, geneticists have concluded that the last female common ancestor whose genetic marker is found in all modern humans, the so-called mitochondrial Eve, must have lived around 200,000 years ago.

Genetics

Human evolutionary genetics studies how one human genome differs from the other, the evolutionary past that gave rise to it, and its current effects. Differences between genomes have anthropological, medical and forensic implications and applications. Genetic data can provide important insight into human evolution.

Evidence from the fossil record

There is little fossil evidence for the divergence of the gorilla, chimpanzee and hominin lineages.[92] The earliest fossils that have been proposed as members of the hominin lineage are Sahelanthropus tchadensis dating from 7 million years ago, Orrorin tugenensis dating from 5.7 million years ago, and Ardipithecus kadabba dating to 5.6 million years ago. Each of these have been argued to be a bipedal ancestor of later hominins but, in each case, the claims have been contested. It is also possible that one or more of these species are ancestors of another branch of African apes, or that they represent a shared ancestor between hominins and other apes.

The question then of the relationship between these early fossil species and the hominin lineage is still to be resolved. From these early species, the australopithecines arose around 4 million years ago and diverged into robust (also called Paranthropus) and gracile branches, one of which (possibly A. garhi) probably went on to become ancestors of the genus Homo. The australopithecine species that is best represented in the fossil record is Australopithecus afarensis with more than one hundred fossil individuals represented, found from Northern Ethiopia (such as the famous "Lucy"), to Kenya, and South Africa. Fossils of robust australopithecines such as Au. robustus (or alternatively Paranthropus robustus) and Au./P. boisei are particularly abundant in South Africa at sites such as Kromdraai and Swartkrans, and around Lake Turkana in Kenya.

The earliest member of the genus Homo is Homo habilis which evolved around 2.8 million years ago.[93] Homo habilis is the first species for which we have positive evidence of the use of stone tools. They developed the Oldowan lithic technology, named after the Olduvai Gorge in which the first specimens were found. Some scientists consider Homo rudolfensis, a larger bodied group of fossils with similar morphology to the original H. habilis fossils, to be a separate species while others consider them to be part of H. habilis—simply representing intraspecies variation, or perhaps even sexual dimorphism. The brains of these early hominins were about the same size as that of a chimpanzee, and their main adaptation was bipedalism as an adaptation to terrestrial living.

During the next million years, a process of encephalization began and, by the arrival (about 1.9 million years ago) of Homo erectus in the fossil record, cranial capacity had doubled. Homo erectus were the first of the hominins to emigrate from Africa, and, from 1.8 to 1.3 million years ago, this species spread through Africa, Asia, and Europe. One population of H. erectus, also sometimes classified as a separate species Homo ergaster, remained in Africa and evolved into Homo sapiens. It is believed that these species, H. erectus and H. ergaster, were the first to use fire and complex tools.

The earliest transitional fossils between H. ergaster/erectus and archaic H. sapiens are from Africa, such as Homo rhodesiensis, but seemingly transitional forms were also found at Dmanisi, Georgia. These descendants of African H. erectus spread through Eurasia from ca. 500,000 years ago evolving into H. antecessor, H. heidelbergensis and H. neanderthalensis. The earliest fossils of anatomically modern humans are from the Middle Paleolithic, about 200,000 years ago such as the Omo remains of Ethiopia; later fossils from Es Skhul cave in Israel and Southern Europe begin around 90,000 years ago (0.09 million years ago).

As modern humans spread out from Africa, they encountered other hominins such as Homo neanderthalensis and the so-called Denisovans, who may have evolved from populations of Homo erectus that had left Africa around 2 million years ago. The nature of interaction between early humans and these sister species has been a long-standing source of controversy, the question being whether humans replaced these earlier species or whether they were in fact similar enough to interbreed, in which case these earlier populations may have contributed genetic material to modern humans.[94][95]

This migration out of Africa is estimated to have begun about 70,000 years BP and modern humans subsequently spread globally, replacing earlier hominins either through competition or hybridization. They inhabited Eurasia and Oceania by 40,000 years BP, and the Americas by at least 14,500 years BP.[96]

Before Homo

Early evolution of primates

Evolutionary history of the primates can be traced back 65 million years.[97] One of the oldest known primate-like mammal species, the Plesiadapis, came from North America;[98] another, Archicebus, came from China.[99] Other similar basal primates were widespread in Eurasia and Africa during the tropical conditions of the Paleocene and Eocene.

David R. Begun [100] concluded that early primates flourished in Eurasia and that a lineage leading to the African apes and humans, including to Dryopithecus, migrated south from Europe or Western Asia into Africa. The surviving tropical population of primates—which is seen most completely in the Upper Eocene and lowermost Oligocene fossil beds of the Faiyum depression southwest of Cairo—gave rise to all extant primate species, including the lemurs of Madagascar, lorises of Southeast Asia, galagos or "bush babies" of Africa, and to the anthropoids, which are the Platyrrhines or New World monkeys, the Catarrhines or Old World monkeys, and the great apes, including humans and other hominids.

The earliest known catarrhine is Kamoyapithecus from uppermost Oligocene at Eragaleit in the northern Great Rift Valley in Kenya, dated to 24 million years ago.[101] Its ancestry is thought to be species related to Aegyptopithecus, Propliopithecus, and Parapithecus from the Faiyum, at around 35 million years ago.[102] In 2010, Saadanius was described as a close relative of the last common ancestor of the crown catarrhines, and tentatively dated to 29–28 million years ago, helping to fill an 11-million-year gap in the fossil record.[103]

In the Early Miocene, about 22 million years ago, the many kinds of arboreally adapted primitive catarrhines from East Africa suggest a long history of prior diversification. Fossils at 20 million years ago include fragments attributed to Victoriapithecus, the earliest Old World monkey. Among the genera thought to be in the ape lineage leading up to 13 million years ago are Proconsul, Rangwapithecus, Dendropithecus, Limnopithecus, Nacholapithecus, Equatorius, Nyanzapithecus, Afropithecus, Heliopithecus, and Kenyapithecus, all from East Africa.

The presence of other generalized non-cercopithecids of Middle Miocene from sites far distant—Otavipithecus from cave deposits in Namibia, and Pierolapithecus and Dryopithecus from France, Spain and Austria—is evidence of a wide diversity of forms across Africa and the Mediterranean basin during the relatively warm and equable climatic regimes of the Early and Middle Miocene. The youngest of the Miocene hominoids, Oreopithecus, is from coal beds in Italy that have been dated to 9 million years ago.

Molecular evidence indicates that the lineage of gibbons (family Hylobatidae) diverged from the line of great apes some 18–12 million years ago, and that of orangutans (subfamily Ponginae) diverged from the other great apes at about 12 million years; there are no fossils that clearly document the ancestry of gibbons, which may have originated in a so-far-unknown South East Asian hominoid population, but fossil proto-orangutans may be represented by Sivapithecus from India and Griphopithecus from Turkey, dated to around 10 million years ago.[16]

Divergence of the human clade from other great apes

Species close to the last common ancestor of gorillas, chimpanzees and humans may be represented by Nakalipithecus fossils found in Kenya and Ouranopithecus found in Greece. Molecular evidence suggests that between 8 and 4 million years ago, first the gorillas, and then the chimpanzees (genus Pan) split off from the line leading to the humans. Human DNA is approximately 98.4% identical to that of chimpanzees when comparing single nucleotide polymorphisms (see human evolutionary genetics). The fossil record, however, of gorillas and chimpanzees is limited; both poor preservation—rain forest soils tend to be acidic and dissolve bone—and sampling bias probably contribute to this problem.

Other hominins probably adapted to the drier environments outside the equatorial belt; and there they encountered antelope, hyenas, dogs, pigs, elephants, horses, and others. The equatorial belt contracted after about 8 million years ago, and there is very little fossil evidence for the split—thought to have occurred around that time—of the hominin lineage from the lineages of gorillas and chimpanzees. The earliest fossils argued by some to belong to the human lineage are Sahelanthropus tchadensis (7 Ma) and Orrorin tugenensis (6 Ma), followed by Ardipithecus (5.5–4.4 Ma), with species Ar. kadabba and Ar. ramidus.

It has been argued in a study of the life history of Ar. ramidus that the species provides evidence for a suite of anatomical and behavioral adaptations in very early hominins unlike any species of extant great ape.[104] This study demonstrated affinities between the skull morphology of Ar. ramidus and that of infant and juvenile chimpanzees, suggesting the species evolved a juvenalised or paedomorphic craniofacial morphology via heterochronic dissociation of growth trajectories. It was also argued that the species provides support for the notion that very early hominins, akin to bonobos (Pan paniscus) the less aggressive species of chimpanzee, may have evolved via the process of self-domestication. Consequently, arguing against the so-called "chimpanzee referential model"[105] the authors suggest it is no longer tenable to use common chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) social and mating behaviors in models of early hominin social evolution. When commenting on the absence of aggressive canine morphology in Ar. ramidus and the implications this has for the evolution of hominin social psychology, they wrote:

Of course Ar. ramidus differs significantly from bonobos, bonobos having retained a functional canine honing complex. However, the fact that Ar. ramidus shares with bonobos reduced sexual dimorphism, and a more paedomorphic form relative to chimpanzees, suggests that the developmental and social adaptations evident in bonobos may be of assistance in future reconstructions of early hominin social and sexual psychology. In fact the trend towards increased maternal care, female mate selection and self-domestication may have been stronger and more refined in Ar. ramidus than what we see in bonobos.[104]:128

The authors argue that many of the basic human adaptations evolved in the ancient forest and woodland ecosystems of late Miocene and early Pliocene Africa. Consequently, they argue that humans may not represent evolution from a chimpanzee-like ancestor as has traditionally been supposed. This suggests many modern human adaptations represent phylogenetically deep traits and that the behavior and morphology of chimpanzees may have evolved subsequent to the split with the common ancestor they share with humans.

Genus Australopithecus

The Australopithecus genus evolved in eastern Africa around 4 million years ago before spreading throughout the continent and eventually becoming extinct 2 million years ago. During this time period various forms of australopiths existed, including Australopithecus anamensis, Au. afarensis, Au. sediba, and Au. africanus. There is still some debate among academics whether certain African hominid species of this time, such as Au. robustus and Au. boisei, constitute members of the same genus; if so, they would be considered to be Au. robust australopiths whilst the others would be considered Au. gracile australopiths. However, if these species do indeed constitute their own genus, then they may be given their own name, the Paranthropus.

- Australopithecus (4–1.8 Ma), with species Au. anamensis, Au. afarensis, Au. africanus, Au. bahrelghazali, Au. garhi, and Au. sediba;

- Kenyanthropus (3–2.7 Ma), with species K. platyops;

- Paranthropus (3–1.2 Ma), with species P. aethiopicus, P. boisei, and P. robustus

A new proposed species Australopithecus deyiremeda is claimed to have been discovered living at the same time period of Au. afarensis. There is debate if Au. deyiremeda is a new species or is Au. afarensis.[106] Australopithecus prometheus, otherwise known as Little Foot has recently been dated at 3.67 million years old through a new dating technique, making the Australopithecus genus as old as the Afarensis.[107] Given the opposable big toe found on Little Foot, it seems that he was a good climber, and it is thought given the night predators of the region, he probably, like gorillas and chimpanzees, built a nesting platform at night, in the trees.

Evolution of genus Homo

The earliest documented representative of the genus Homo is Homo habilis, which evolved around 2.8 million years ago,[93] and is arguably the earliest species for which there is positive evidence of the use of stone tools. The brains of these early hominins were about the same size as that of a chimpanzee, although it has been suggested that this was the time in which the human SRGAP2 gene doubled, producing a more rapid wiring of the frontal cortex. During the next million years a process of rapid encephalization occurred, and with the arrival of Homo erectus and Homo ergaster in the fossil record, cranial capacity had doubled to 850 cm3.[108] (Such an increase in human brain size is equivalent to each generation having 125,000 more neurons than their parents.) It is believed that Homo erectus and Homo ergaster were the first to use fire and complex tools, and were the first of the hominin line to leave Africa, spreading throughout Africa, Asia, and Europe between 1.3 to 1.8 million years ago.

According to the recent African origin of modern humans theory, modern humans evolved in Africa possibly from Homo heidelbergensis, Homo rhodesiensis or Homo antecessor and migrated out of the continent some 50,000 to 100,000 years ago, gradually replacing local populations of Homo erectus, Denisova hominins, Homo floresiensis and Homo neanderthalensis.[109][110][111][112][113] Archaic Homo sapiens, the forerunner of anatomically modern humans, evolved in the Middle Paleolithic between 400,000 and 250,000 years ago.[114][115][116] Recent DNA evidence suggests that several haplotypes of Neanderthal origin are present among all non-African populations, and Neanderthals and other hominins, such as Denisovans, may have contributed up to 6% of their genome to present-day humans, suggestive of a limited inter-breeding between these species.[78][117][80] The transition to behavioral modernity with the development of symbolic culture, language, and specialized lithic technology happened around 50,000 years ago according to some anthropologists[118] although others point to evidence that suggests that a gradual change in behavior took place over a longer time span.[119]

Homo sapiens is the only extant species of its genus, Homo. While some (extinct) Homo species might have been ancestors of Homo sapiens, many, perhaps most, were likely "cousins", having speciated away from the ancestral hominin line.[121][122] There is yet no consensus as to which of these groups should be considered a separate species and which should be a subspecies; this may be due to the dearth of fossils or to the slight differences used to classify species in the Homo genus.[122] The Sahara pump theory (describing an occasionally passable "wet" Sahara desert) provides one possible explanation of the early variation in the genus Homo.

Based on archaeological and paleontological evidence, it has been possible to infer, to some extent, the ancient dietary practices[30] of various Homo species and to study the role of diet in physical and behavioral evolution within Homo.[27][123][124][125][126]

Some anthropologists and archaeologists subscribe to the Toba catastrophe theory, which posits that the supereruption of Lake Toba on Sumatran island in Indonesia some 70,000 years ago caused global consequences,[127] killing the majority of humans and creating a population bottleneck that affected the genetic inheritance of all humans today.[128]

H. habilis and H. gautengensis

Homo habilis lived from about 2.8[93] to 1.4 Ma. The species evolved in South and East Africa in the Late Pliocene or Early Pleistocene, 2.5–2 Ma, when it diverged from the australopithecines. Homo habilis had smaller molars and larger brains than the australopithecines, and made tools from stone and perhaps animal bones. One of the first known hominins, it was nicknamed 'handy man' by discoverer Louis Leakey due to its association with stone tools. Some scientists have proposed moving this species out of Homo and into Australopithecus due to the morphology of its skeleton being more adapted to living on trees rather than to moving on two legs like Homo sapiens.[129]

In May 2010, a new species, Homo gautengensis, was discovered in South Africa.[130]

H. rudolfensis and H. georgicus

These are proposed species names for fossils from about 1.9–1.6 Ma, whose relation to Homo habilis is not yet clear.

- Homo rudolfensis refers to a single, incomplete skull from Kenya. Scientists have suggested that this was another Homo habilis, but this has not been confirmed.[131]

- Homo georgicus, from Georgia, may be an intermediate form between Homo habilis and Homo erectus,[132] or a sub-species of Homo erectus.[133]

H. ergaster and H. erectus

The first fossils of Homo erectus were discovered by Dutch physician Eugene Dubois in 1891 on the Indonesian island of Java. He originally named the material Pithecanthropus erectus based on its morphology, which he considered to be intermediate between that of humans and apes.[134] Homo erectus lived from about 1.8 Ma to about 70,000 years ago—which would indicate that they were probably wiped out by the Toba catastrophe; however, nearby Homo floresiensis survived it. The early phase of Homo erectus, from 1.8 to 1.25 Ma, is considered by some to be a separate species, Homo ergaster, or as Homo erectus ergaster, a subspecies of Homo erectus.

In Africa in the Early Pleistocene, 1.5–1 Ma, some populations of Homo habilis are thought to have evolved larger brains and to have made more elaborate stone tools; these differences and others are sufficient for anthropologists to classify them as a new species, Homo erectus—in Africa.[135] The evolution of locking knees and the movement of the foramen magnum are thought to be likely drivers of the larger population changes. This species also may have used fire to cook meat. Richard Wrangham suggests that the fact that Homo seems to have been ground dwelling, with reduced intestinal length, smaller dentition, "and swelled our brains to their current, horrendously fuel-inefficient size",[136] suggest that control of fire and releasing increased nutritional value through cooking was the key adaptation that separated Homo from tree-sleeping Australopitheicines.[137]

A famous example of Homo erectus is Peking Man; others were found in Asia (notably in Indonesia), Africa, and Europe. Many paleoanthropologists now use the term Homo ergaster for the non-Asian forms of this group, and reserve Homo erectus only for those fossils that are found in Asia and meet certain skeletal and dental requirements which differ slightly from H. ergaster.

H. cepranensis and H. antecessor

These are proposed as species that may be intermediate between H. erectus and H. heidelbergensis.

- H. antecessor is known from fossils from Spain and England that are dated 1.2 Ma–500 ka.[138][139]

- H. cepranensis refers to a single skull cap from Italy, estimated to be about 800,000 years old.[140]

H. heidelbergensis

.jpg)

H. heidelbergensis ("Heidelberg Man") lived from about 800,000 to about 300,000 years ago. Also proposed as Homo sapiens heidelbergensis or Homo sapiens paleohungaricus.[141]

H. rhodesiensis, and the Gawis cranium

- H. rhodesiensis, estimated to be 300,000–125,000 years old. Most current researchers place Rhodesian Man within the group of Homo heidelbergensis, though other designations such as archaic Homo sapiens and Homo sapiens rhodesiensis have been proposed.

- In February 2006 a fossil, the Gawis cranium, was found which might possibly be a species intermediate between H. erectus and H. sapiens or one of many evolutionary dead ends. The skull from Gawis, Ethiopia, is believed to be 500,000–250,000 years old. Only summary details are known, and the finders have not yet released a peer-reviewed study. Gawis man's facial features suggest its being either an intermediate species or an example of a "Bodo man" female.[142]

Neanderthal and Denisovan

Homo neanderthalensis, alternatively designated as Homo sapiens neanderthalensis,[143] lived in Europe and Asia from 400,000[144] to about 28,000 years ago.[145] There are a number of clear anatomical differences between anatomically modern humans (AMH) and Neanderthal populations. Many of these relate to the superior adaption to cold environments possessed by the Neanderthal populations. Their surface to volume ratio is an extreme version of that found amongst Inuit populations, indicating that they were less inclined to lose body heat than were AMH. From brain Endocasts, Neanderthals also had significantly larger brains. This would seem to indicate that the intellectual superiority of AMH populations may be questionable. More recent research by Eiluned Pearce, Chris Stringer, R. I. M. Dunbar, however, have shown important differences in Brain architecture. For example, in both the orbital chamber size and in the size of the occipital lobe, the larger size suggests that the Neanderthal had a better visual acuity than modern humans. This would give a superior vision in the inferior light conditions found in Glacial Europe. It also seems that the higher body mass of Neanderthals had a correspondingly larger brain mass required for body care and control. The Neanderthal populations seem to have been physically superior to AMH populations. These differences may have been sufficient to give Neanderthal populations an environmental superiority to AMH populations from 75 to 45,000 years BP. With these differences, Neanderthal brains show a smaller area was available for social functioning. Plotting group size possible from endocrainial volume, suggests that AMH populations (minus occipital lobe size), had a Dunbars number of 144 possible relationships. Neanderthal populations seem to have been limited to about 120 individuals. This would show up in a larger number of possible mates for AMH humans, with increased risks of inbreeding amongst Neanderthal populations. It also suggests that humans had larger trade catchment areas than Neanderthals (confirmed in the distribution of stone tools). With larger populations, social and technological innovations were easier to fix in human populations, which may have all contributed to the fact that modern Homo sapiens replaced the Neanderthal populations by 28,000 BP.[146]

Earlier evidence from sequencing mitochondrial DNA suggested that no significant gene flow occurred between H. neanderthalensis and H. sapiens, and that the two were separate species that shared a common ancestor about 660,000 years ago.[147][148][149] However, a sequencing of the Neanderthal genome in 2010 indicated that Neanderthals did indeed interbreed with anatomically modern humans circa 45,000 to 80,000 years ago (at the approximate time that modern humans migrated out from Africa, but before they dispersed into Europe, Asia and elsewhere).[150] The genetic sequencing of a human from Romania dated 40,000 years ago showed that 11% of their genome was Neanderthal. This would indicate that this individual had a Neanderthal great grandparent, 4 generations previously. It seems that this individual has left no living descendants.

Nearly all modern non-African humans have 1% to 4% of their DNA derived from Neanderthal DNA,[150] and this finding is consistent with recent studies indicating that the divergence of some human alleles dates to one Ma, although the interpretation of these studies has been questioned.[151][152] Neanderthals and Homo sapiens could have co-existed in Europe for as long as 10,000 years, during which human populations exploded vastly outnumbering Neanderthals, possibly outcompeting them by sheer numerical strength.[153]

In 2008, archaeologists working at the site of Denisova Cave in the Altai Mountains of Siberia uncovered a small bone fragment from the fifth finger of a juvenile member of Denisovans.[154] Artifacts, including a bracelet, excavated in the cave at the same level were carbon dated to around 40,000 BP. As DNA had survived in the fossil fragment due to the cool climate of the Denisova Cave, both mtDNA and nuclear DNA were sequenced.[78][155]

While the divergence point of the mtDNA was unexpectedly deep in time,[156] the full genomic sequence suggested the Denisovans belonged to the same lineage as Neanderthals, with the two diverging shortly after their line split from the lineage that gave rise to modern humans.[78] Modern humans are known to have overlapped with Neanderthals in Europe and the Near East for possibly more than 40,000 years,[157] and the discovery raises the possibility that Neanderthals, Denisovans, and modern humans may have co-existed and interbred. The existence of this distant branch creates a much more complex picture of humankind during the Late Pleistocene than previously thought.[155][158] Evidence has also been found that as much as 6% of the DNA of some modern Melanesians derive from Denisovans, indicating limited interbreeding in Southeast Asia.[79][159]

Alleles thought to have originated in Neanderthals and Denisovans have been identified at several genetic loci in the genomes of modern humans outside of Africa. HLA haplotypes from Denisovans and Neanderthal represent more than half the HLA alleles of modern Eurasians,[80] indicating strong positive selection for these introgressed alleles. Corinne Simoneti at Vanderbilt University, in Nashville and her team have found from medical records of 28,000 people of European descent that the presence of Neanderthal DNA segments may be associated with a likelihood to suffer depression more frequently.[160]

The flow of genes from Neanderthal populations to modern human was not all one way. Sergi Castellano of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, has in 2016 reported that while Denisovan and Neanderthal genomes are more related to each other than they are to us, Siberian Neanderthal genomes show similarity to the modern human gene pool, more so than to European Neanderthal populations. The evidence suggests that the Neanderthal populations interbred with modern humans possibly 100,000 years ago, probably somewhere in the Near East.[161]

Studies of a Neanderthal child at Gibraltar show from brain development and teeth eruption that Neanderthal children may have matured more rapidly than is the case for Homo sapiens.[162]

H. floresiensis

H. floresiensis, which lived from approximately 190,000 to 50,000 years before present, has been nicknamed hobbit for its small size, possibly a result of insular dwarfism.[163] H. floresiensis is intriguing both for its size and its age, being an example of a recent species of the genus Homo that exhibits derived traits not shared with modern humans. In other words, H. floresiensis shares a common ancestor with modern humans, but split from the modern human lineage and followed a distinct evolutionary path. The main find was a skeleton believed to be a woman of about 30 years of age. Found in 2003, it has been dated to approximately 18,000 years old. The living woman was estimated to be one meter in height, with a brain volume of just 380 cm3 (considered small for a chimpanzee and less than a third of the H. sapiens average of 1400 cm3).

However, there is an ongoing debate over whether H. floresiensis is indeed a separate species.[164] Some scientists hold that H. floresiensis was a modern H. sapiens with pathological dwarfism.[165] This hypothesis is supported in part, because some modern humans who live on Flores, the Indonesian island where the skeleton was found, are pygmies. This, coupled with pathological dwarfism, could have resulted in a significantly diminutive human. The other major attack on H. floresiensis as a separate species is that it was found with tools only associated with H. sapiens.[165]

The hypothesis of pathological dwarfism, however, fails to explain additional anatomical features that are unlike those of modern humans (diseased or not) but much like those of ancient members of our genus. Aside from cranial features, these features include the form of bones in the wrist, forearm, shoulder, knees, and feet. Additionally, this hypothesis fails to explain the find of multiple examples of individuals with these same characteristics, indicating they were common to a large population, and not limited to one individual.

H. sapiens

H. sapiens (the adjective sapiens is Latin for "wise" or "intelligent") have lived from about 250,000 years ago to the present. Between 400,000 years ago and the second interglacial period in the Middle Pleistocene, around 250,000 years ago, the trend in intra-cranial volume expansion and the elaboration of stone tool technologies developed, providing evidence for a transition from H. erectus to H. sapiens. The direct evidence suggests there was a migration of H. erectus out of Africa, then a further speciation of H. sapiens from H. erectus in Africa. A subsequent migration (both within and out of Africa) eventually replaced the earlier dispersed H. erectus. This migration and origin theory is usually referred to as the "recent single-origin hypothesis" or "out of Africa" theory. Current evidence does not preclude some multiregional evolution or some admixture of the migrant H. sapiens with existing Homo populations. This is a hotly debated area of paleoanthropology.

Current research has established that humans are genetically highly homogenous; that is, the DNA of individuals is more alike than usual for most species, which may have resulted from their relatively recent evolution or the possibility of a population bottleneck resulting from cataclysmic natural events such as the Toba catastrophe.[166][167] Distinctive genetic characteristics have arisen, however, primarily as the result of small groups of people moving into new environmental circumstances. These adapted traits are a very small component of the Homo sapiens genome, but include various characteristics such as skin color and nose form, in addition to internal characteristics such as the ability to breathe more efficiently at high altitudes.

H. sapiens idaltu, from Ethiopia, is an extinct sub-species from about 160,000 years ago who is argued to be the direct ancestor of all modern humans.

| Species | Temporal range kya | Habitat | Adult height | Adult mass | Cranial capacity (cm³) | Fossil record | Discovery / publication of name |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H. habilis | 2,100 – 1,500[168] | Africa | 110-140 cm (4 ft 11 in) | 33–55 kg (73–121 lb) | 510–660 | Many | 1960/1964 |

| H. erectus | 1,900 – 70 | Africa, Eurasia (Java, China, India, Caucasus) | 180 cm (5 ft 11 in) | 60 kg (130 lb) | 850 (early) – 1,100 (late) | Many[170] | 1891/1892 |

| H. rudolfensis membership in Homo uncertain |

1,900 | Kenya | 700 | 2 sites | 1972/1986 | ||

| H. gautengensis also classified as H. habilis |

1,900 – 600 | South Africa | 100 cm (3 ft 3 in) | 3 individuals[171] | 2010/2010 | ||

| H. ergaster also classified as H. erectus |

1,800 – 1,300[172] | Eastern and Southern Africa | 700–850 | Many | 1975 | ||

| H. antecessor also classified as H. heidelbergensis |

1,200 – 800 | Spain | 175 cm (5 ft 9 in) | 90 kg (200 lb) | 1,000 | 2 sites | 1997 |

| H. cepranensis a single fossil, possibly H. erectus |

900 – 350 | Italy | 1,000 | 1 skull cap | 1994/2003 | ||

| H. heidelbergensis | 600 – 350[173] | Europe, Africa, China | 180 cm (5 ft 11 in) | 90 kg (200 lb) | 1,100–1,400 | Many | 1908 |

| H. neanderthalensis possibly a subspecies of H. sapiens |

350 – 40[174] | Europe, Western Asia | 170 cm (5 ft 7 in) | 55–70 kg (121–154 lb) (heavily built) | 1,200–1,900 | Many | (1829)/1864 |

| H. naledi |

335–236 | South Africa | 150 centimetres (4 ft 11 in) tall | 45 kilograms (99 lb) | 450 | 15 individuals | 2013/2015 |

| H. tsaichangensis possibly H. erectus |

190 – 10[175] | Taiwan | 1 individual | pre-2008/2015 | |||

| H. rhodesiensis also classified as H. heidelbergensis |

300 – 120 | Zambia | 1,300 | Very few | 1921 | ||

| H. sapiens (modern humans) |

300[176][177]

– present |

Worldwide | 150 - 190 cm (4 ft 7 in - 6 ft 3 in) | 50–100 kg (110–220 lb) | 950–1,800 | (extant) | —/1758 |

| H. floresiensis classification uncertain |

190 – 50 | Indonesia | 100 cm (3 ft 3 in) | 25 kg (55 lb) | 400 | 7 individuals | 2003/2004 |

| Denisova hominin possible H. sapiens subspecies or hybrid |

40 | Russia | 1 site | 2000/2010 | |||

| Red Deer Cave people possible H. sapiens subspecies or hybrid |

14.5–11.5 | China | Very few | 2012 |

|

Use of tools

The use of tools has been interpreted as a sign of intelligence, and it has been theorized that tool use may have stimulated certain aspects of human evolution, especially the continued expansion of the human brain.[178] Paleontology has yet to explain the expansion of this organ over millions of years despite being extremely demanding in terms of energy consumption. The brain of a modern human consumes about 13 watts (260 kilocalories per day), a fifth of the body's resting power consumption.[179] Increased tool use would allow hunting for energy-rich meat products, and would enable processing more energy-rich plant products. Researchers have suggested that early hominins were thus under evolutionary pressure to increase their capacity to create and use tools.[180]

Precisely when early humans started to use tools is difficult to determine, because the more primitive these tools are (for example, sharp-edged stones) the more difficult it is to decide whether they are natural objects or human artifacts.[178] There is some evidence that the australopithecines (4 Ma) may have used broken bones as tools, but this is debated.[181]

It should be noted that many species make and use tools, but it is the human genus that dominates the areas of making and using more complex tools. The oldest known tools are the Oldowan stone tools from Ethiopia, 2.5–2.6 million years old. A Homo fossil was found near some Oldowan tools, and its age was noted at 2.3 million years old, suggesting that maybe the Homo species did indeed create and use these tools. It is a possibility but does not yet represent solid evidence.[182] The third metacarpal styloid process enables the hand bone to lock into the wrist bones, allowing for greater amounts of pressure to be applied to the wrist and hand from a grasping thumb and fingers. It allows humans the dexterity and strength to make and use complex tools. This unique anatomical feature separates humans from apes and other nonhuman primates, and is not seen in human fossils older than 1.8 million years.[183]

Bernard Wood noted that Paranthropus co-existed with the early Homo species in the area of the "Oldowan Industrial Complex" over roughly the same span of time. Although there is no direct evidence which identifies Paranthropus as the tool makers, their anatomy lends to indirect evidence of their capabilities in this area. Most paleoanthropologists agree that the early Homo species were indeed responsible for most of the Oldowan tools found. They argue that when most of the Oldowan tools were found in association with human fossils, Homo was always present, but Paranthropus was not.[182]

In 1994, Randall Susman used the anatomy of opposable thumbs as the basis for his argument that both the Homo and Paranthropus species were toolmakers. He compared bones and muscles of human and chimpanzee thumbs, finding that humans have 3 muscles which are lacking in chimpanzees. Humans also have thicker metacarpals with broader heads, allowing more precise grasping than the chimpanzee hand can perform. Susman posited that modern anatomy of the human opposable thumb is an evolutionary response to the requirements associated with making and handling tools and that both species were indeed toolmakers.[182]

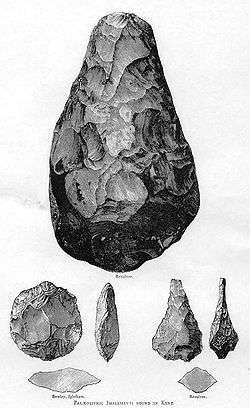

Stone tools

Stone tools are first attested around 2.6 Million years ago, when H. habilis in Eastern Africa used so-called pebble tools, choppers made out of round pebbles that had been split by simple strikes.[184] This marks the beginning of the Paleolithic, or Old Stone Age; its end is taken to be the end of the last Ice Age, around 10,000 years ago. The Paleolithic is subdivided into the Lower Paleolithic (Early Stone Age), ending around 350,000–300,000 years ago, the Middle Paleolithic (Middle Stone Age), until 50,000–30,000 years ago, and the Upper Paleolithic, (Late Stone Age), 50,000-10,000 years ago.

Archaeologists working in the Great Rift Valley in Kenya claim to have discovered the oldest known stone tools in the world. Dated to around 3.3 million years ago, the implements are some 700,000 years older than stone tools from Ethiopia that previously held this distinction.[185][186][187]

The period from 700,000–300,000 years ago is also known as the Acheulean, when H. ergaster (or erectus) made large stone hand axes out of flint and quartzite, at first quite rough (Early Acheulian), later "retouched" by additional, more-subtle strikes at the sides of the flakes. After 350,000 BP the more refined so-called Levallois technique was developed, a series of consecutive strikes, by which scrapers, slicers ("racloirs"), needles, and flattened needles were made.[184] Finally, after about 50,000 BP, ever more refined and specialized flint tools were made by the Neanderthals and the immigrant Cro-Magnons (knives, blades, skimmers). In this period they also started to make tools out of bone.

Transition to behavioral modernity

Until about 50,000–40,000 years ago, the use of stone tools seems to have progressed stepwise. Each phase (H. habilis, H. ergaster, H. neanderthalensis) started at a higher level than the previous one, but after each phase started, further development was slow. Currently paleoanthropologists are debating whether these Homo species possessed some or many of the cultural and behavioral traits associated with modern humans such as language, complex symbolic thinking, technological creativity etc. It seems that they were culturally conservative maintaining simple technologies and foraging patterns over very long periods.

Around 50,000 BP, modern human culture started to evolve more rapidly. The transition to behavioral modernity has been characterized by most as a Eurasian "Great Leap Forward",[188] or as the "Upper Palaeolithic Revolution",[189] due to the sudden appearance of distinctive signs of modern behavior and big game hunting[190] in the archaeological record. Some other scholars consider the transition to have been more gradual, noting that some features had already appeared among archaic African Homo sapiens since 200,000 years ago.[191][192] Recent evidence suggests that the Australian Aboriginal population separated from the African population 75,000 years ago, and that they made a sea journey of up to 160 km 60,000 years ago, which may diminish the evidence of the Upper Paleolithic Revolution.[193]

Modern humans started burying their dead, using animal hides to make clothing, hunting with more sophisticated techniques (such as using trapping pits or driving animals off cliffs), and engaging in cave painting.[194] As human culture advanced, different populations of humans introduced novelty to existing technologies: artifacts such as fish hooks, buttons, and bone needles show signs of variation among different populations of humans, something that had not been seen in human cultures prior to 50,000 BP. Typically, H. neanderthalensis populations do not vary in their technologies, although the Chatelperronian assemblages have been found to be Neanderthal innovations produced as a result of exposure to the Homo sapiens Aurignacian technologies.[195]

Among concrete examples of modern human behavior, anthropologists include specialization of tools, use of jewellery and images (such as cave drawings), organization of living space, rituals (for example, burials with grave gifts), specialized hunting techniques, exploration of less hospitable geographical areas, and barter trade networks. Debate continues as to whether a "revolution" led to modern humans ("the big bang of human consciousness"), or whether the evolution was more "gradual".[119]

Recent and current human evolution

Natural selection still affects modern human populations. For example, the population at risk of the severe debilitating disease kuru has significant over-representation of an immune variant of the prion protein gene G127V versus non-immune alleles. The frequency of this genetic variant is due to the survival of immune persons.[196][197] Other reported trends appear to include lengthening of the human reproductive period and reduction in cholesterol levels, blood glucose and blood pressure in some populations .[198]

It has been argued that human evolution has accelerated since the development of agriculture 10,000 years ago and civilization some 5,000 years ago, resulting, it is claimed, in substantial genetic differences between different current human populations.[199] Lactase persistence is an example of such recent evolution. Recent human evolution seems to have been largely confined to genetic resistance to infectious disease that has appeared in human populations by crossing the species barrier from domesticated animals.[200]

It is a common misconception that humans have stopped evolving and current genetic changes are purely genetic drift. Although selection pressure on some traits, such as resistance to smallpox, has decreased in modern human life, humans are still undergoing natural selection for many other traits. For instance, menopause is evolving to occur later.[198]

Species list

This list is in chronological order across the table by genus. Some species/subspecies names are well-established, and some are less established – especially in genus Homo. Please see articles for more information.

See also

- Adaptive evolution in the human genome

- The Ancestor's Tale

- Archaeogenetics

- Chimpanzee–human last common ancestor

- Dawn of Humanity (2015 PBS documentary)

- Dual inheritance theory

- Dysgenics

- Evolution of hair

- Evolution of human intelligence

- Evolution of morality

- Evolutionary anthropology

- Evolutionary medicine

- Evolutionary neuroscience

- Evolutionary origin of religions

- Evolutionary psychology

- Hominidae

- Human behavioral ecology

- Human evolution (origins of society and culture)

- Human skeletal changes due to bipedalism

- Human vestigiality

- List of human evolution fossils

- March of Progress

- Molecular paleontology

- Noogenesis

- Origin of language

- Origin of speech

- Obstetrical dilemma

- Prehistoric Autopsy (2012 BBC documentary)

- Prehistory

- Recent African origin of modern humans

- Sahara pump theory

- Sexual selection in human evolution

- Timeline of human evolution

References

- ↑ Brian K. Hall; Benedikt Hallgrímsson (2011). Strickberger's Evolution. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. p. 488. ISBN 978-1-4496-6390-2.

- ↑ Heng, Henry H. Q. (May 2009). "The genome-centric concept: resynthesis of evolutionary theory". BioEssays. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. 31 (5): 512–525. ISSN 0265-9247. PMID 19334004. doi:10.1002/bies.200800182.

- ↑ Tyson, Peter (July 1, 2008). "Meet Your Ancestors". NOVA scienceNOW. PBS; WGBH Educational Foundation. Retrieved 2015-04-18.

- 1 2 Dawkins 2004

- "Find Time of Divergence: Hominidae versus Hylobatidae". TimeTree. Retrieved 2015-04-18.

- ↑ Boyd & Silk 2003

- ↑ Brues & Snow 1965, pp. 1–39

- ↑ Brunet, Michel; Guy, Franck; Pilbeam, David; et al. (July 11, 2002). "A new hominid from the Upper Miocene of Chad, Central Africa". Nature. London: Nature Publishing Group. 418 (6894): 145–151. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 12110880. doi:10.1038/nature00879.

- 1 2 Kwang Hyun, Ko (2015). "Origins of Bipedalism". Brazilian Archives of Biology and Technology. 58: 929–934. doi:10.1590/S1516-89132015060399.

- 1 2 DeSalle & Tattersall 2008, p. 146

- 1 2 Curry 2008, pp. 106–109

- ↑ "Study Identifies Energy Efficiency As Reason For Evolution Of Upright Walking". ScienceDaily. Rockville, MD: ScienceDaily, LLC. July 17, 2007. Retrieved 2015-04-09.

- "Study identifies energy efficiency as reason for evolution of upright walking". UANews. Tucson, AZ: The University of Arizona Office of University Communications. July 16, 2007. Retrieved 2015-04-23.

- ↑ Sockol, Michael D.; Raichlen, David A.; Pontzer, Herman (July 24, 2007). "Chimpanzee locomotor energetics and the origin of human bipedalism". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. Washington, D.C.: National Academy of Sciences. 104 (30): 12265–12269. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 1941460

. PMID 17636134. doi:10.1073/pnas.0703267104.

. PMID 17636134. doi:10.1073/pnas.0703267104. - ↑ David-Barrett, T.; Dunbar, R.I.M. (2016). "Bipedality and Hair-loss Revisited: The Impact of Altitude and Activity Scheduling". Journal of Human Evolution. 94: 72–82. PMC 4874949

. PMID 27178459. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2016.02.006.

. PMID 27178459. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2016.02.006. - ↑ Aiello & Dean 1990

- ↑ Kondo 1985

- 1 2 Srivastava 2009, p. 87

- ↑ Strickberger 2000, pp. 475–476

- ↑ Trevathan 2011, p. 20

- ↑ Zuk, Marlene (2014), "Paleofantasy: What Evolution Really Tells Us About Sex, Diet, and How We Live" (W. W. Norton & Company)

- ↑ Hrdy, Sarah Blaffer (2011), "Mothers and Others: The Evolutionary Origins of Mutual Understanding" (Harvard Uni Press)

- ↑ Wayman, Erin (August 19, 2013). "Killer whales, grandmas and what men want: Evolutionary biologists consider menopause". Science News. Washington, D.C.: Society for Science & the Public. ISSN 0036-8423. Retrieved 2015-04-24.