Punched card

A punched card or punch card is a piece of stiff paper that can be used to contain digital information represented by the presence or absence of holes in predefined positions. The information might be data for data processing applications or, in earlier examples, used to directly control automated machinery.

Punched cards were widely used through much of the 20th century in what became known as the data processing industry, where specialized and increasingly complex unit record machines, organized into semiautomatic data processing systems, used punched cards for data input, output, and storage.[1][2] Many early digital computers used punched cards, often prepared using keypunch machines, as the primary medium for input of both computer programs and data.

While punched cards are now obsolete as a recording medium, as of 2012, some voting machines still use punched cards to record votes.[3]

History

Basile Bouchon developed the control of a loom by punched holes in paper tape in 1725. The design was improved by his assistant Jean-Baptiste Falcon and Jacques Vaucanson (1740)[4] Although these improvements controlled the patterns woven, they still required an assistant to operate the mechanism. In 1804 Joseph Marie Jacquard demonstrated a mechanism to automate loom operation. A number of punched cards were linked into a chain of any length. Each card held the instructions for shedding (raising and lowering the warp) and selecting the shuttle for a single pass. It is considered an important step in the history of computing hardware.[5]

Semen Korsakov was reputedly the first to use the punched cards in informatics for information store and search. Korsakov announced his new method and machines in September 1832; rather than seeking patents, he offered the machines for public use.[6][7]

Charles Babbage proposed the use of "Number Cards", "pierced with certain holes and stand opposite levers connected with a set of figure wheels ... advanced they push in those levers opposite to which there are no holes on the card and thus transfer that number" in his description of the Calculating Engine's Store.[8]

In 1881 Jules Carpentier developed a method of recording and playing back performances on a harmonium using punched cards. The system was called the Mélographe Répétiteur and “writes down ordinary music played on the keyboard dans la langage de Jacquard”,[9] that is as holes punched in a series of cards. By 1887 Carpentier had separated the mechanism into the Melograph which recorded the player's key presses and the Melotrope which played the music.[10][11]

Herman Hollerith invented the recording of data on a medium that could then be read by a machine. Prior uses of machine readable media, such as those above (other than Korsakov, Fenby and Carpentier), had been for control, not data. "After some initial trials with paper tape, he settled on punched cards...", developing punched card data processing technology for the 1890 US census.[12]

Hollerith founded the Tabulating Machine Company (1896) which was one of four companies that were amalgamated (via stock acquisition) to form a fifth company, Computing-Tabulating-Recording Company (CTR), later renamed International Business Machines Corporation (IBM). Other companies entering the punched card business included The Tabulator Limited (1902) later renamed the British Tabulating Machine Company Limited, Deutsche Hollerith-Maschinen Gesellschaft mbH (Dehomag) (1911), Powers Accounting Machine Company (1911) , Remington Rand (1927), and Groupe Bull (1931).[13] These companies, and others, manufactured and marketed a variety of punched cards and unit record machines for creating, sorting, and tabulating punched cards, even after the development of electronic computers in the 1950s.

Both IBM and Remington Rand tied punched card purchases to machine leases, a violation of the 1914 Clayton Antitrust Act. In 1932, the US government took both to court on this issue. Remington Rand settled quickly. IBM viewed its business as providing a service and that the cards were part of the machine. IBM fought all the way to the Supreme Court and lost in 1936; the court ruling that IBM could only set card specifications.[14][15]

"By 1937... IBM had 32 presses at work in Endicott, N.Y., printing, cutting and stacking five to 10 million punched cards every day."[16] Punched cards were even used as legal documents, such as U.S. Government checks[17] and savings bonds.

During WW II punched card equipment was used by the Allies in some of their efforts to decrypt Axis communications. See, for example, Central Bureau. At Bletchley Park 2,000,000 punched cards were used each week for storing decrypted German messages.[18]

Punched card technology developed into a powerful tool for business data-processing. By 1950 punched cards had become ubiquitous in industry and government. "Do not fold, spindle or mutilate," a generalized version of the warning that appeared on some punched cards (generally on those distributed as paper documents to be later returned for further machine processing, checks for example), became a motto for the post-World War II era.[19][20]

In 1955 IBM signed a consent decree requiring, amongst other things, that IBM would by 1962 have no more than one-half of the punched card manufacturing capacity in the United States. Tom Watson Jr.'s decision to sign this decree, where IBM saw the punched card provisions as the most significant point, completed the transfer of power to him from Thomas Watson, Sr.[21]

The UNITYPER introduced magnetic tape for data entry in the 1950s. During the 1960s, the punched card was gradually replaced as the primary means for data storage by magnetic tape, as better, more capable computers became available. Mohawk Data Sciences introduced a magnetic tape encoder in 1965, a system marketed as a keypunch replacement which was somewhat successful. Punched cards were still commonly used for entering both data and computer programs until the mid-1980s when the combination of lower cost magnetic disk storage, and affordable interactive terminals on less expensive minicomputers made punched cards obsolete for these roles as well.[22] However, their influence lives on through many standard conventions and file formats. The terminals that replaced the punched cards, the IBM 3270 for example, displayed 80 columns of text in text mode, for compatibility with existing software. Some programs still operate on the convention of 80 text columns, although fewer and fewer do as newer systems employ graphical user interfaces with variable-width type fonts.

Nomenclature

The terms punched card, punch card, and punchcard were all commonly used, as were IBM card and Hollerith card (after Herman Hollerith).[23] IBM used "IBM card" or, later, "punched card" at first mention in its documentation and thereafter simply "card" or "cards".[24][25] Specific formats were often indicated by the number of character positions available, e.g. 80-column card. A sequence of cards that is input to or output from some step in an application's processing is called a card deck or simply deck. The rectangular, round, or oval bits of paper punched out were called chad (chads) or chips (in IBM usage). Sequential card columns allocated for a specific use, such as names, addresses, multi-digit numbers, etc., are known as a field. The first card of a group of cards, containing fixed or indicative information for that group, is known as a master card. Cards that are not master cards are detail cards.

Card formats

The Hollerith punched cards used for the US 1890 census were blank.[26] Following that, cards commonly had printing such that the row and column position of a hole could be easily seen. Printing could include having fields named and marked by vertical lines, logos, and more.[27] "General purpose" layouts (see, for example, the IBM 5081 below) were also available. For applications requiring master cards to be separated from following detail cards, the respective cards had different upper corner diagonal cuts and thus could be separated by a sorter.[28] Other cards typically had one upper corner diagonal cut so that cards not oriented correctly, or cards with different corner cuts, could be identified.

Hollerith's early punched card formats

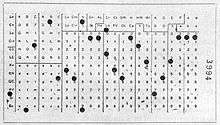

Herman Hollerith was awarded a series of patents[30] in 1889 for electromechanical tabulating machines. These patents described both paper tape and rectangular cards as possible recording media. The card shown in U.S. Patent 395,781 of June 8 was printed with a template and had hole positions arranged close to the edges so they could be reached by a railroad conductor's ticket punch, with the center reserved for written descriptions. Hollerith was originally inspired by railroad tickets that let the conductor encode a rough description of the passenger:

- "I was traveling in the West and I had a ticket with what I think was called a punch photograph...the conductor...punched out a description of the individual, as light hair, dark eyes, large nose, etc. So you see, I only made a punch photograph of each person."[31]

Use of the ticket punch proved tiring and error prone, so Hollerith invented a pantograph "keyboard punch". It featured an enlarged diagram of the card, indicating the positions of the holes to be punched. A printed reading board could be placed under a card that was to be read manually.[32]

Hollerith envisioned a number of card sizes. In an article he wrote describing his proposed system for tabulating the 1890 U.S. Census, Hollerith suggested a card 3 inches by 5½ inches of Manila stock "would be sufficient to answer all ordinary purposes."[33] The cards used in the 1890 census had round holes, 12 rows and 24 columns. A reading board for these cards can be seen at the Columbia University Computing History site.[34] At some point, 3 1⁄4 by 7 3⁄8 inches (82.6 by 187.3 mm) became the standard card size. These are the dimensions of the then current paper currency of 1862–1923.[35]

Hollerith's original system used an ad-hoc coding system for each application, with groups of holes assigned specific meanings, e.g. sex or marital status. His tabulating machine had up to 40 counters, each with a dial divided into 100 divisions, with two indicator hands; one which stepped one unit with each counting pulse, the other which advanced one unit every time the other dial made a complete revolution. This arrangement allowed a count up to 10,000. During a given tabulating run, each counter was typically assigned a specific hole. Hollerith also used relay logic to allow counts of combination of holes, e.g. to count married females.[33]

Later designs led to a card with ten rows, each row assigned a digit value, 0 through 9, and 45 columns.[36] This card provided for fields to record multi-digit numbers that tabulators could sum, instead of their simply counting cards. Hollerith's 45 column punched cards are illustrated in Comrie's The application of the Hollerith Tabulating Machine to Brown's Tables of the Moon.[37][38]

IBM 80-column punched card format and character codes

By the late 1920’s customers wanted to store more data on each card. Thomas J. Watson Sr., IBM’s head, ask two of his top inventors, Clair D. Lake and J. Royden Peirce, to independently develop ways to increase data capacity without increasing the size of the card. Pierce wanted to keep round holes and 45 columns, but allow each column to store more data. Lake suggested rectangular holes, which could be spaced more tightly, allowing 80 numbers per card, thereby nearly doubling the capacity of the older format.[39] Watson picked the latter solution, introduced as The IBM Computer Card, in part because it was compatible with existing tabulator designs and in part because it could be protected by patents and give the company a distinctive advantage.[40]

This IBM card format, introduced in 1928,[41] has rectangular holes, 80 columns, and 12 rows with one character to each column. Card size is exactly 7 3⁄8 by 3 1⁄4 inches (187.325 mm × 82.55 mm). The cards are made of smooth stock, 0.007 inches (180 µm) thick. There are about 143 cards to the inch (56/cm). In 1964, IBM changed from square to round corners.[42] They come typically in boxes of 2000 cards[43] or as continuous form cards. Continuous form cards could be both pre-numbered and pre-punched for document control (checks, for example).[44]

The top two positions of a column are called zone punches, 12 (top) and 11. For decimal data the lower ten positions represent (from top to bottom) the digits 0 through 9. An arithmetic sign can be specified for a decimal field by overpunching the field's rightmost column with a zone punch: 12 for plus, 11 for minus (CR). For Pound sterling pre-decimalization currency a pence column represented the values zero through eleven; 10 (top), 11, then 0 through 9 as above. An arithmetic sign can be punched in the adjacent shilling column.[45] Zone punches had other uses in processing, such as indicating a master card.[46]

______________________________________________

/&-0123456789ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQR/STUVWXYZ

12| x xxxxxxxxx

11| x xxxxxxxxx

0| x xxxxxxxxx

1| x x x x

2| x x x x

3| x x x x

4| x x x x

5| x x x x

6| x x x x

7| x x x x

8| x x x x

9| x x x x

|________________________________________________

Reference:[47] Note: The 11 and 12 zones were also called the X and Y zones, respectively.

In 1931 IBM began introducing multiple punches for upper-case letters and special characters.[48][49] A letter has two punches (zone [12,11,0] + digit [1–9]); most special characters have two or three punches (zone [12,11,0,or none] + digit [2–7] + 8); a few special characters were exceptions (in EBCDIC "&" is 12 only, "-" is 11 only, and "/" is 0 + 1). With these changes, the information represented in a column by a combination of zones [12, 11] and digits [1–9] is dependent on the use of that column. For example, the combination "12-1" is the letter "A" in an alphabetic column, a plus signed digit "1" in a signed numeric column, or an unsigned digit "1" in a column where the "12" have some other use. The introduction of EBCDIC in 1964 allowed columns with as many as six punches (zones [12,11,0,8,9] + digit [1–7]). IBM and other manufacturers used many different 80-column card character encodings.[50][51] A 1969 American National Standard defined the punches for 128 characters and was named the Hollerith Punched Card Code (often referred to simply as Hollerith Card Code), honoring Hollerith.[52]

For some computer applications, binary formats were used, where each hole represented a single binary digit (or "bit"), every column (or row) is treated as a simple bit field, and every combination of holes is permitted.

As a prank, in binary mode, cards could be punched where every possible punch position had a hole. Such "lace cards" lacked structural strength, and would frequently buckle and jam inside the machine.[53]

The 80-column card format dominated the industry, becoming known as just IBM cards, even though other companies made cards and equipment to process them.

One of the most common punched card formats is the IBM 5081 card format, a general purpose layout with no field divisions. This format has digits printed on it corresponding to the punch positions of the digits in each of the 80 columns. Other card vendors manufactured cards with this same layout and number.

IBM Stub card or Short card formats

The 80-column card could be scored, on either end, creating a stub that could be torn off, leaving a stub card or short card. A common length for stub cards was 51-columns. Stub cards were used in applications requiring tags, labels, or carbon copies.[44]

IBM 40-column Port-A-Punch card format

According to the IBM Archive: IBM's Supplies Division introduced the Port-A-Punch in 1958 as a fast, accurate means of manually punching holes in specially scored IBM punched cards. Designed to fit in the pocket, Port-A-Punch made it possible to create punched card documents anywhere. The product was intended for "on-the-spot" recording operations—such as physical inventories, job tickets and statistical surveys—because it eliminated the need for preliminary writing or typing of source documents.[54]

IBM 96-column punched card format

In the early 1970s, IBM introduced a new, smaller, round-hole, 96-column card format along with the IBM System/3 computer. These cards have tiny (1 mm), circular holes, smaller than those in paper tape. Data is stored in six-bit binary-coded decimal code, with three rows of 32 characters each, or 8-bit EBCDIC. In this format, each column of the top tiers are combined with two punch rows from the bottom tier to form an 8-bit byte, and the middle tier is combined with two more punch rows, so that each card contains 64 bytes of 8-bit-per-byte binary coded data.[55]

Powers/Remington Rand UNIVAC 90-column punched card format

The Powers/Remington Rand card format was initially the same as Hollerith's; 45 columns and round holes. In 1930, Remington Rand leap-frogged IBM's 80 column format from 1928 by coding two characters in each of the 45 columns – producing what is now commonly called the 90-column card.[56] There are two sets of six rows across each card. The rows in each set are labeled 0, 1/2, 3/4, 5/6, 7/8 and 9. The even numbers in a pair are formed by combining that punch with a 9 punch. Alphabetic and special characters use 3 or more punches[57][58]

Powers-Samas punched card formats

The Powers-Samas card formats began with 45 columns and round holes. Later 36, 40 and 65 column cards were provided. A 130 column card was also available - formed by dividing the card into two rows, each row with 65 columns and each character space with 5 punch positions. A 21 column card was comparable to the IBM Stub card.[59]

Mark sense card format

- Mark sense (Electrographic) cards, developed by Reynold B. Johnson at IBM, have printed ovals that could be marked with a special electrographic pencil. Cards would typically be punched with some initial information, such as the name and location of an inventory item. Information to be added, such as quantity of the item on hand, would be marked in the ovals. Card punches with an option to detect mark sense cards could then punch the corresponding information into the card.

Aperture card format

- Aperture cards have a cut-out hole on the right side of the punched card. A 35 mm microfilm chip containing a microform image is mounted in the hole. Aperture cards are used for engineering drawings from all engineering disciplines. Information about the drawing, for example the drawing number, is typically punched and printed on the remainder of the card.

IBM punched card manufacturing

IBM's Fred M. Carroll[60] developed a series of rotary type presses that were used to produce the well-known standard tabulating cards, including a 1921 model that operated at 400 cards per minute (cpm). Later, he developed a completely different press capable of operating at speeds in excess of 800 cpm, and it was introduced in 1936.[16][61] Carroll's high-speed press, containing a printing cylinder, revolutionized the manufacture of punched tabulating cards.[62] It is estimated that between 1930 and 1950, the Carroll press accounted for as much as 25 percent of the company's profits.[21]

Discarded printing plates from these card presses, each printing plate the size of an IBM card and formed into a cylinder, often found use as desk pen/pencil holders, and even today are collectible IBM artifacts (every card layout[63] had its own printing plate).

Cultural impact

While punched cards have not been widely used for a generation, the impact was so great for most of the 20th century that they still appear from time to time in popular culture. For example:

- Artist and architect Maya Lin in 2004 designed a public art installation at Ohio University, titled "Input", that looks like a punched card from the air.[64]

- The Man Whose Name Wouldn't Fit: a book by Theodore Tyler[65]

- The warning often printed on cards that were to be individually handled, "Do not fold, spindle or mutilate", coined by Charles A. Phillips, became a motto for the post-World War II era (even though many people had no idea what spindle meant). [66] The motto was also used for a book by Doris Miles Disney and a movie based on that book.[67]

- Tucker Hall at the University of Missouri - Columbia features architecture that is reportedly influenced by computer punched cards. It is said that the spacing and pattern of the windows on the building will print out “M-I-Z beat k-U!” on a punched card, making reference to the University and state's rivalry with neighboring state Kansas.[68]

- At the University of Wisconsin - Madison, the exterior windows of the Engineering Research Building[69] were modeled after a punched card layout, during its construction in 1966.

- At the University of North Dakota, the exterior of Gamble Hall, College of Business and Public Administration has a punch card spelling out "University of North Dakota."[70]

- In the Simpsons episode "Much Apu About Nothing", Apu showed Bart his Ph.D. thesis, the world's first computer tic-tac-toe game, stored in a box full of punched cards.

- In the Futurama episode "Mother's Day", as several robots are seen shouting 'Hey hey! Hey ho! 100110!' in protest, one of them burns a punch-card in a manner reminiscent of draft-card burning. In another episode, Put Your Head on My Shoulders, Bender offers a dating service. He hands characters punch-cards so they can put in what they want, before throwing them in his chest cabinet and 'calculating' the 'match' for the person. Bender is shown 'folding', 'bending', and 'mutilating' the card, accentuating the fact that he is making up the 'calculations'.

- In the 1964–65 Free Speech Movement, punched cards became a

metaphor... symbol of the "system"—first the registration system and then bureaucratic systems more generally ... a symbol of alienation ... Punched cards were the symbol of information machines, and so they became the symbolic point of attack. Punched cards, used for class registration, were first and foremost a symbol of uniformity. .... A student might feel "he is one of out of 27,500 IBM cards" ... The president of the Undergraduate Association criticized the University as "a machine ... IBM pattern of education."... Robert Blaumer explicated the symbolism: he referred to the "sense of impersonality... symbolized by the IBM technology."... ––Steven Lubar[71]

- A legacy of the 80 column punched card format is that a display of 80 characters per row was a common choice in the design of character-based terminals. As of September 2014, some character interface defaults, such as the command prompt window's width in Microsoft Windows, remain set at 80 columns and some file formats, such as FITS, still use 80-character card images.

- In Arthur C. Clarke's early short story "Rescue Party", the alien explorers find a "... wonderful battery of almost human Hollerith analyzers and the five thousand million punched cards holding all that could be recorded on each man, woman and child on the planet". Writing in 1946, Clarke, like almost all sci-fi authors, had not then foreseen the development and eventual ubiquity of the computer.

Standards

- ANSI INCITS 21-1967 (R2002), Rectangular Holes in Twelve-Row Punched Cards (formerly ANSI X3.21-1967 (R1997)) Specifies the size and location of rectangular holes in twelve-row 3 1⁄4-inch-wide (83 mm) punched cards.

- ANSI X3.11 – 1990 American National Standard Specifications for General Purpose Paper Cards for Information Processing

- ANSI X3.26 – 1980/R1991) Hollerith Punched Card Code

- ISO 1681:1973 Information processing – Unpunched paper cards – Specification

- ISO 6586:1980 Data processing – Implementation of the ISO 7- bit and 8- bit coded character sets on punched cards. Defines ISO 7-bit and 8-bit character sets on punched cards as well as the representation of 7-bit and 8-bit combinations on 12-row punched cards. Derived from, and compatible with, the Hollerith Code, ensuring compatibility with existing punched card files.

Card handling machines

Creation and processing of punched cards was handled by a variety of machines, including:

- Keypunches — machines with a keyboard that punch cards from operator entered data

- Unit record equipment — machines that process data on punched cards. Employed prior to the widespread use of digital computers. Included card sorters, tabulating machines and a variety of other machines

- Punched card input/output — machines that allowed punched cards to be used with digital computers

- Voting machines — used into the 21st century

See also

- Aperture card

- Card image

- Computer programming in the punched card era

- History of computing hardware

- Kimball tag—punched card price tags

- Paper data storage

- Punched tape

References

- The initial version of this article, October 18, 2001, was based on material taken from the Free On-line Dictionary of Computing and incorporated under the "relicensing" terms of the GFDL, version 1.1.

- ↑ Cortada, James W. (1993) Before The Computer: IBM, NCR, Burroughs, & Remington Rand & The Industry They Created, 1865-1965, Princeton

- ↑ Brooks, Frederick P.; Iverson, Kenneth E. (1963). Automatic Data Processing. Wiley. p. 94 "semiautomatic".

- ↑ "Nightly News Aired on December 27, 2012 - Punch card voting lingers". Video.msnbc.msn.com. Retrieved 2013-10-05.

- ↑ Razy, C. (1913). Étude analytique des petits modèles de métiers exposés au musée des tissus. Lyon, France: Musée historique des tissus. p. 120.

- ↑ Essinger, James (2007-03-29). Jacquard's Web: How a Hand-loom Led to the Birth of the Information Age. OUP Oxford. pp. 35–40. ISBN 9780192805782.

- ↑ Semen Korsakov's inventions, Cybernetics Dept. of MEPhI (in Russian)

- ↑ Trogemann, Georg (eds.); et al. (2001). Computing in Russia. Verlag. pp. 47–49. The article is by Gellius N. Povarov, titled Semen Nikolayevich Korsakov- Machines for the Comparison of Philosophical Ideas

- ↑ Babbage, Charles (26 Dec 1837). On the Mathematical Powers of the Calculating Engine.

- ↑ Southgate, Thomas Lea (1881). "On Various Attempts That Have Been Made to Record Extemporaneous Playing". Journal of the Royal Musical Association. 8 (1): 189–196. cited by Seaver (2010)

- ↑ Seaver, Nicholas Patrick (June 2010). A Brief History of Re-performance (PDF) (Thesis). Massachusetts Institute of Technology. p. 34. Retrieved 21 June 2017.

- ↑ The Pianola Institute (2016). "The Reproducing Piano - Early Experiments". www.pianola.com. Retrieved 25 June 2017.

At this early stage, the corresponding playback mechanism, the Mélotrope, was permanently installed inside the same harmonium used for the recording process, but by 1887 Carpentier had modified both devices, restricting the range to three octaves, allowing for the Mélotrope to be attached to any style of keyboard instrument, and designing and constructing an automatic perforating machine for mass production.

- ↑ "Columbia University Computing History – Herman Hollerith". Columbia University, Columbia.edu. Retrieved 2013-10-05.

- ↑ A History of Sperry Rand Corporation (4th ed.). Sperry Rand. 1967. p. 32.

- ↑ "International Business Machines Corp. v. United States, 298 U.S. 131 (1936)". Justia.

- ↑ Belden (1962) pp.300-301

- 1 2 "IBM Archive: Endicott card manufacturing". 03.ibm.com. Retrieved 2013-10-05.

- ↑ Lubar, Steven (1993). InfoCulture: The Smithsonian Book of Information Age Inventions. Houghton Mifflin. p. 302. ISBN 0-395-57042-5.

- ↑ Codes and Ciphers Heritage Trust

- ↑ Lubar, Steven, 1991, Do Not Fold, Spindle or Mutilate: A Cultural History of the Punch Card, Smithsonian Institution

- ↑ "History of the punch card". Whatis.techtarget.com. Retrieved 2013-10-05.

- 1 2 Belden, Thomas; Belden, Marva (1962). The Lengthening Shadow: The Life of Thomas J. Watson. Little, Brown & Company.

- ↑ Aspray (ed.), W. (1990). Computing before Computers. Iowa State University Press. p. 151. ISBN 0-8138-0047-1.

- ↑ Steven Pinker, in The Stuff of Thought, Viking, 2007, p.362, notes the loss of -ed in pronunciation as it did in ice cream, mincemeat, and box set, formerly iced cream, minced meat, and boxed set.

- ↑ "An important function in IBM Accounting is the automatic preparation of IBM cards." IBM 519 Principles of Operation, Form 22-3292-5, 1946

- ↑ "The IBM 1402 Card Read-Punch provides the system with simultaneous punched-card input and output. This unit has two card feeds." Reference Manual 1401 Data Processing System, Form A24-1403-4, 1961

- ↑ Truedsell, Leon E. (1965). The Development of Punch Card Tabulation in the Bureau of the Census 1890-1940. US GPO.

- ↑ IBM (1956). The Design of IBM Cards (PDF). 22-5526-4.

- ↑ IBM (1962). Reference Manual - IBM 82, 83, and 84 Sorters. p. 25. A24-1034.

- ↑ "Hollerith's Electric Tabulating Machine". Railroad Gazette. April 19, 1895. Retrieved 2015-06-04.

- ↑ U.S. Patent 395,781, U.S. Patent 395,782, U.S. Patent 395,783

- ↑ (Austrian 1982, p.15)

- ↑ (Truesdell 1965, p.43)

- 1 2 "An Electric Tabulating System". The Quarterly. Columbia University School of Mines. 10 (16): 245. April 1889.

- ↑ "Columbia University Computing History: Hollerith 1890 Census Tabulator". Columbia University, Columbia.edu. Retrieved 2013-10-05.

- ↑ Littleton Coin Company. "Large-Size U.S. Paper Money". Littleton Coin Company. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

- ↑ Bashe, Charles J.; Johnson, Lyle R.; Palmer, John H.; Pugh, Emerson W. (1986). IBM's Early Computers. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press. p. 5. ISBN 0-262-02225-7. Also see pages 5-14 for additional information on punched cards.

- ↑ Plates from: Comrie, L.J. (1932). "The application of the Hollerith Tabulating Machine to Brown's Tables of the Moon". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 92 (7): 694–707. Bibcode:1932MNRAS..92..694C. doi:10.1093/mnras/92.7.694.

- ↑ Comrie, L.J. (1932). "The application of the Hollerith tabulating machine to Brown's tables of the moon". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 92 (7): 694–707. Bibcode:1932MNRAS..92..694C. doi:10.1093/mnras/92.7.694. Retrieved 2009-04-17.

- ↑ U.S. Patent 1,772,492, Record Sheet for Tabulating Machines, C. D. Lake, filed June 20, 1928

- ↑ The IBM Punched Card, IBM100

- ↑ IBM Archive: 1928.

- ↑ IBM Archive: Old/New-Cards.

- ↑ p. 405, "How Computational Chemistry Became Important in the Pharmaceutical Industry", Donald B. Boyd, chapter 7 in Reviews in Computational Chemistry, Volume 23, edited by Kenny B. Lipkowitz, Thomas R. Cundari and Donald B. Boyd, Wiley & Son, 2007, ISBN 978-0-470-08201-0.

- 1 2 IBM (1953). Principles of IBM Accounting. 224-5527-2.

- ↑ Cemach, 1951, p.9, 17. Cemach has examples of shillings as 2 columns (p.9) and 1 column (p.17). This text assumes that 2 columns was normal, that 1 column was the exception.

- ↑ IBM Operator's Guide A24-1010, 1959, p.141: Master Card: The first card of a group containing fixed or indicative information for that group

- ↑ "Punched Card Codes". Cs.uiowa.edu. Retrieved 2013-10-05.

- ↑ Pugh, Emerson W. (1995). Building IBM: Shaping and Industry and Its Technology. MIT Press. pp. 50–51. ISBN 978-0-262-16147-3.

- ↑ Special characters are non-alphabetic, non-numeric, such as "&#,$.-/@%*?"

- ↑ Winter, Dik T. "80-column Punched Card Codes". Archived from the original on April 8, 2007. Retrieved November 6, 2012.

- ↑ Jones, Douglas W. "Punched Card Codes". Retrieved February 20, 2007.

- ↑ Mackenzie, Charles E. (1980). Coded Character Sets, History and Development. The Systems Programming Series (1 ed.). Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, Inc. p. 7. ISBN 0-201-14460-3. LCCN 77-90165.

- ↑ Raymond, Eric S. (1991). The New Hacker's Dictionary. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. p. 219.

- ↑ "IBM Archive: Port-A-Punch". 03.ibm.com. Retrieved 2013-10-05.

- ↑ Winter, Dik T. "96-column Punched Card Code". Archived from the original on April 15, 2007. Retrieved November 6, 2012.

- ↑ Aspray (ed.). op. cit. p. 142.

- ↑ "The Punched Card". Quadibloc.com. Retrieved 2013-10-05.

- ↑ Winter, Dik T. "90-column Punched Card Code". Archived from the original on February 28, 2005. Retrieved November 6, 2012.

- ↑ (Cemach, 1951, pp 47-51)

- ↑ "IBM Archives/Business Machines: Fred M. Carroll". 03.ibm.com. Retrieved 2013-10-05.

- ↑ "IBM Archives: Fred M. Carroll". 03.ibm.com. Retrieved 2013-10-05.

- ↑ "IBM Archives: (IBM) Carroll Press". 03.ibm.com. Retrieved 2013-10-05.

- ↑ "IBM Archives:1939 Layout department". 03.ibm.com. Retrieved 2013-10-05.

- ↑ "Mayalin.com". Mayalin.com. 2009-01-08. Retrieved 2013-10-05.

- ↑ Tyler, Theodore (1968). The Man Whose Name Wouldn't Fit. Doubleday Science Fiction. p. 262.

- ↑ Lee, J.A.L. (1995) Computer Pioneers, IEEE, p.557

- ↑ Disney, Doris Miles (1970). Do Not Fold, Spindle or Mutilate. Crime Club. p. 183.

- ↑ "Mizzou Alumni Association- Campus Traditions". Mizzou Alumni Association. Mizzou Alumni Association. Retrieved 21 April 2016.

- ↑ "University of Wisconsin-Madison Buildings:". Fpm.wisc.edu. Retrieved 2013-10-05.

- ↑ "Photo of Gamble Hall by gatty790". Panoramio.com. Retrieved 2013-10-05.

- ↑ Lubar, Steven. "Do Not Fold, Spindle Or Mutilate: A Cultural History Of The Punch Card" (PDF). Journal of American Culture. 1992 (Winter). Retrieved June 12, 2011.

Further reading

- Austrian, Geoffrey D. (1982). Herman Hollerith: The Forgotten Giant of Information Processing. Columbia University Press. p. 418. ISBN 0-231-05146-8.

- Cemach, Harry P. (1951). The Elements of Punched Card Accounting. Sir Issac Pitman & Sons Ltd. p. 137. Machine illustrations were provided by Power-Samas Accounting Machines and British Tabulating Machine Co.

- Fierheller, George A. (2006). Do not fold, spindle or mutilate: the "hole" story of punched cards (PDF). Stewart Pub. ISBN 1-894183-86-X. Retrieved March 30, 2011. An accessible book of recollections (sometimes with errors), with photographs and descriptions of many unit record machines.

- Murray, Francis J. (1961). Mathematical Machines Volume 1: Digital Computers. Columbia University Press. Includes a description of Samas punched cards and illustration of an Underwood Samas punched card.

- Truedsell, Leon E. (1965). The Development of Punch Card Tabulation in the Bureau of the Census 1890-1940. US GPO. Includes extensive, detailed, description of Hollerith's first machines and their use for the 1890 census.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Punch card. |

- IBM. "The IBM Punched Card". Retrieved April 25, 2014.

- Lubar, Steve (May 1991). "Do not fold, spindle or mutilate: A cultural history of the punch card". Archived from the original on 2006-08-30.

- Jones, Douglas W. "Punched Cards". Retrieved October 20, 2006. (Collection shows examples of left, right, and no corner cuts.)

- VintageTech – a U.S. company that converts punched cards to conventional media

- Dyson, George (March 1999). "The Undead". Wired magazine. 7 (3). Retrieved 2017-07-04. article about modern-day use of punched cards

- Williams, Robert V. (2002). "Punched Cards: A Brief Tutorial". IEEE Annals – Web extra. Retrieved 2015-03-26.

- UNIVAC Punch Card Gallery (Shows examples of both left and right corner cuts.)

- Cardamation at the Wayback Machine (archived October 17, 2011) – a U.S. company that supplied punched card equipment and supplies until 2011.

- An Emulator for Punched cards

- Brian De Palma (Director) (1961). 660124: The Story of an IBM Card (Film).

- Povarov G.N. Semen Nikolayevich Korsakov. Machines for the Comparison of Philosophical Ideas. In: Trogemann, Georg; Ernst, Wolfgang and Nitussov, Alexander, Computing in Russia: The History of Computer Devices and Information Technology Revealed (pp 47–49), Verlag, 2001. Translated by Alexander Y. Nitussov. ISBN 3-528-05757-2, ISBN 978-3-528-05757-2

- Korsakov S.N. A Depiction of a New Research Method, Using Machines which Compare Ideas, Ed. by Alexander Mikhailov, MEPhI, 2009 (in Russian)