Hohokam

The Hohokam (/hoʊhoʊˈkɑːm/) were an ancient Native American culture centered in the present US state of Arizona. The Hohokam are one of the four major cultures of the American Southwest and northern Mexico in Southwestern archaeology. Considered part of the Oasisamerica tradition, the Hohokam established significant trading centers such as at Snaketown, and are considered to be the builders of the original canal system around the Phoenix metropolitan area, which the Mormon pioneers rebuilt when they settled the Lehi area of Mesa near Red Mountain. Variant spellings in current, official usage include Hobokam, Huhugam, and Huhukam.

The Hohokam culture was differentiated from others in the region in the 1930s by archaeologist Harold S. Gladwin, who applied the existing O'odham term for the culture, huhu-kam, meaning "all used up"[1] or "those who are gone",[2] to classify the remains he was excavating in the Lower Gila Valley. According to the National Park Service Website, Hohokam is an O'odham word used by archaeologists to identify a group of people who lived in the Sonoran Desert.

According to local oral tradition, the Hohokam may be the ancestors of the historic Pima and Tohono O'odham peoples in Southern Arizona. Recent academic research focused on the Sobaipuri, ancient ancestors of the modern Pima, indicates that Pima groups were present in the region at the end of the Hohokam sequence.

Overview

Hohokam, a term borrowed from the O'odham language, is used to define an archaeological culture that existed from the beginning of the common era to about the middle of the 15th century. As an abstract construct, this culture was centered on the middle Gila and lower Salt River drainages[3] in what is known as the Phoenix basin. This is referred to as the Hohokam Core Area, as opposed to the Hohokam Peripheries; or adjacent regions into which the Hohokam Culture extended. Collectively, the Core and Peripheries formed what is referred to as the Hohokam Regional System, which occupied the northern or Upper Sonoran Desert in what is now Arizona. The Hohokam also extended into the Mogollon Rim region.

Within a larger context, the Hohokam culture area inhabited a central trade position between the Patayan situated along the Lower Colorado River and in southern California; the Trincheras of Sonora, Mexico; the Mogollon culture in eastern Arizona, southwest New Mexico, and northwest Chihuahua, Mexico; and the Ancestral Puebloans in northern Arizona, northern New Mexico, southwest Colorado, and southern Utah.

In North America, the Hohokam were the only culture to rely on irrigation canals to water their crops since as early as 800, and their irrigation systems supported the largest population in the Southwest by 1300.[4] Archaeologists working at a major archaeological dig in the 1990s in the Tucson Basin, along the Santa Cruz River, identified a culture and people that were ancestors of the Hohokam[5] who might have occupied southern Arizona as early as 2000 BCE.[4] This prehistoric group from the Early Agricultural Period grew corn, lived year-round in sedentary villages, and developed sophisticated irrigation canals.[4]

The Hohokam used the waters of the Salt and Gila Rivers and constructed an assortment of simple canals combined with weirs in their various agricultural pursuits. Since the 9th century and extending into the 15th century,[6] they maintained what was to become extensive irrigation networks that rivaled the complexity of those used in the ancient Near East, Egypt, and China. These were constructed using relatively simple excavation tools, without the benefit of advanced engineering technologies, and achieved drops of a few feet per mile, balancing erosion and siltation.[7] Over 70 years of archaeological research has revealed that the Hohokam cultivated varieties of cotton, tobacco, maize, beans, and squash, as well as harvested a vast assortment of wild plants. Late in the Hohokam Chronological Sequence, they also used extensive dry-farming systems, primarily to grow agave for food and fiber. Their reliance on agricultural strategies based on canal irrigation, vital in their less than hospitable desert environment and arid climate, provided the basis for the aggregation of rural populations into stable urban centers.

Overall, Hohokam villages and smaller settlements can be classified within the ranchería-tradition; these typically found near water and arable land, and identified by clusters of residential areas composed of discrete groups of habitation and utility structures combined with extramural use areas. Many features of early Hohokam domestic architecture, such as large square or rectangular pithouses, seem to have been transplanted relatively intact from early Formative Period examples first developed in the Tucson basin. But, by the seventh century, a distinct Hohokam architectural tradition emerged. Throughout the Hohokam Chronological Sequence, individual residential structures were normally excavated approximately 40 cm (16 in) below ground level, with plastered or compacted floors that covered between 12 and 35 m2, and featured a circular, bowl-shaped, clay-lined hearth situated near the wall-entry.

Hohokam burial practices varied over time. Initially, the primary method employed was flexed inhumation, similar to the tradition used by the southern Mogollon culture, located immediately to the east. In the late Formative and Preclassic periods, the Hohokam cremated their dead, again strikingly similar to the traditions documented among the historic Patayan culture situated to the west along the Lower Colorado River. Although the particulars of the practice changed somewhat, the Hohokam cremation tradition remained dominant until around 1300. At this time, extended inhumation, similar to that used by the Salado tradition to the north and northeast, was quickly adopted. Also, many of the details of the late Hohokam burial patterns were very similar to the tradition practiced by the historic Tohono and Akimel O'odham.

The Hohokam chronological sequence

This section provides a brief outline of the Hohokam chronological sequence (HCS) and the methods used to establish its calendrical reference. As an archaeological construct, the HCS uses a culture history-based period/phase scheme designed to provide a narrative of what has been perceived as a sequence of significant cultural change. Overall, the reason the HCS is confusing is that two primary methods of expressing this information are used, and within this context, a vast plethora of theoretical variants have been posited. Only the two primary schemes will be addressed, referred to as the Gladwinian and Cultural Horizon expressions. The latter is an adaptation of the chronological scheme used in Mesoamerica applied to avoid the interpretive bias inherent in the Gladwinian scheme (i.e. Pioneer, Colonial, Sedentary periods).

The HCS is applied only to the Hohokam Core Area, which is the Gila-Salt River basin associated with Phoenix, Arizona, as opposed to what has come to be known as the Hohokam Peripheries. The Hohokam Peripheries are regions located outside the core area. Within these regions, the basic period designations are retained; however, local phases are often used to note significant differences. The cause of these differences and the range of cultural variability within the Hohokam Culture will be addressed below; to some extent, it represents communities influenced by their Ancestral Puebloan and Mogollon neighbors.

Pioneer/Formative Period (AD 1–750)

Living as farmers raising corn and beans, these early Hohokam founded a series of small villages along the middle Gila River. The communities were located near good, arable land, with dry farming common in the earlier years of this period. Water wells, usually less than 10 feet (3 m) deep, were dug for domestic water supplies. Early Hohokam homes were constructed of branches bent in a semicircular fashion and covered with twigs, reeds, and heavily applied mud and other items at hand.

Crop, agricultural skill, and cultural refinements increased between AD 300 and 500 as the Hohokam acquired a new group of cultivated plants, presumably from trade with peoples in the area of modern Mexico. These new acquisitions included cotton, tepary bean, sieva and jack beans, cushaw and warty squash, and southwestern pigweed. Agave species had been gathered for food and fiber for thousands of years by southwestern peoples, but around 600, the Hohokam began cultivating agave, particularly Agave murpheyi ("Hohokam agave"), on large areas of rocky, dry ground. Agave became a major food source for the Hohokam to augment the food grown in irrigated areas.[9] Engineering improved access to river water and the inhabitants excavated canals for irrigation. Evidence of trade networks include turquoise, shells from the Gulf of California, and parrot bones from central Mexico. Seeds and grains were prepared on stone manos and metates. Ceramics appeared shortly before AD 300, with pots of unembellished brown used for storage and cooking, and as containers for cremated remains. Materials produced for ritual use included fired clay human and animal figures and incense burners.

Colonial/Preclassic period (750–1050/1150)

Growth is the major characteristic of the Colonial period. Villages grew larger, with clusters of houses opening on a common courtyard. Some evidence exists of social stratification in larger homes and more ornate grave goods. Area and canal systems expanded, and tobacco and agave production began. Mexican influence increased. In larger communities, the first Hohokam ball courts were constructed and served as focal points for games and ceremonies. Pottery was embellished by the addition of an iron-stained slip, which produced a distinctive red-on-buff ware.

Sedentary period/Sacaton phase (950–1050/1150)

Further population increase brought significant changes during this period. Irrigation canals and structures became larger and required more maintenance. More land came under cultivation, and Southwestern pigweed was grown. House design evolved into post-reinforced pit-houses, covered with caliche adobe. Rancheria-like villages grew up around common courtyards, with evidence of increased communal activity. Large common ovens were used to cook bread and meats.

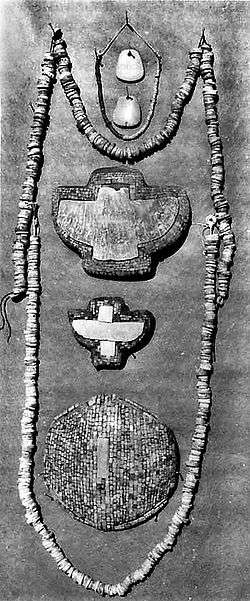

Crafts were dramatically refined. By about AD 1000, the Hohokam are credited with being the first culture to master acid etching. Artisans produced jewelry from shell, stone, and bone, and began to carve stone figures. Cotton textile work flourished. Red-on-buff pottery was widely produced.

This growth brought a need for increased organization, and perhaps authority. The regional culture spread widely, extending from near the Mexican border to the Verde River in the north. There appears to have been an elite class, as well as an increase in social stature for the craftsman. Platform mounds similar to those in central Mexico appear, and may be associated with an upper class and have some religious function. Trade items from the Mexican heartland included copper bells, mosaics, stone mirrors, and ornate birds such as macaws.

Classic period (AD 1050/1150–1450)

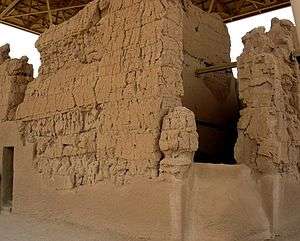

This period can generally be considered a time of both growth and social change. The community of Snaketown, once central to the culture, was suddenly abandoned. Parts of this large village seem to have burned, and thereafter it was never reoccupied. This period also had the construction of large and prestigious structures in the Salt-Gila Basin. These included large, rectangular, adobe-walled compounds with platform mounds and great houses, such as the example found at the Casa Grande Ruins National Monument. Additionally, evidence of Hohokam influence in a broader context decreased significantly.

Santan phase (AD 1050–1150)

This phase was initially proposed as part of the Gladwinian scheme, but recently has fallen out of favor with many Hohokam archaeologists. The primary reason for this view is that the Hohokam buff ware type once classified as Santan red-on-buff is now listed as either a late form of Sacaton or Casa Grande red-on-buffs. The wide range of vessel forms used for decorated pottery was discarded for globular jars with necks, while overall a significant decrease in production and use of Hohokam buff wares occurred, as well as a radical decline in the procurement and trade of raw shell from northern Mexico and its manufacture into jewelry. Another trait of this phase was the transition from pithouses to pitrooms and the introduction of spherical spindle whorls similar to examples used in northern Mexico. Conceptually, this episode had the relatively sudden and widespread abandonment or relocation of many Hohokam villages and a short-lived population decline. Vast internal changes, the rejection of the Hohokam ballcourt system, and the peripheries' displaying overt indications of belligerence towards the core area, followed by their cultural realignment, suggests that this was a very important episode.

Soho phase (AD 1050/1150–1300)

The diagnostic ceramic type for this phase was Casa Grande red-on-buff. This Hohokam buff ware was characterized exclusively by jars with necks, decorated with a limited variety of geometric and textual designs. This pottery type appears to have been manufactured at several locales situated in the Gila River basin between Florence and Sacaton, Arizona. In general, this phase represents a major cultural retraction in terms of territory, and two significant episodes of reorganization. The first reorganization occurred around AD 1150 and was typified by a modest increase in population and near-universal adoption of pitroom architecture. These early pitrooms were built of perishable material covered with a thick adobe plaster, and the basal portion of the interior walls was often lined with upright slabs. Similar to the Preclassic period villages, these early Classic period habitation structures were clustered around open courtyards. These courtyard groups were clustered near a large central locus, which often included small platform mounds. These platform mounds were rectangular, faced by post-reinforced adobe walls, and were filled with either sterile soil or refuse from Preclassic trash mounds. In the largest villages, the central locus included small platform mounds. The number of small and medium-sized settlements seem to have declined as the larger communities became increasingly more densely occupied.

Civano phase (AD 1300–1350/1375)

Although Casa Grande red-on-buff continued to be produced, the pottery type that characterized this phase was Salado polychrome, primarily Gila polychrome. This ceramic type was either manufactured locally or procured as a trade ware. This phase also had the introduction the comal, similar to examples found in northern Mexico, and the production of bird-shaped effigy vessels. Examples of exotic stone and shell artifacts associated with high-status individuals – such as nose plugs, pendants, ear rings, bracelets, necklaces, and sophisticated shell inlays – indicate that the design and manufacture of jewelry reached its zenith during this phase. Other important developments were the significant increased procurement and manufacture of red ware, and the near-universal use of inhumation burial in the area north of the Gila River, both similar to the practices and traditions used by the historic O'odham.

Immediately after AD 1300, Hohokam villages were reorganized along the lines experienced in the Lower Verde, Tonto Basin, and Safford Basin, in the 13th century. These compounds were composed of a large, rectangular exterior wall that either completely or more typically partially enclosed a series of contiguous courtyards and plazas delineated by interior partition walls. In turn, each courtyard may have contained one to as many as four large, rectangular, adobe-walled pitrooms, possibly associated with several utility structures. Overall, these communities were characterized by relatively compact clusters of between five and 25 adobe-walled compounds, which tended to be grouped around a single very large and well-built compound that often had some form of large community structure, such as a platform mound or great house. Great house structures, as with the one preserved at Casa Grande Ruins National Monument, were built only at the largest communities. These stone or adobe buildings had up to four stories, and were probably used by the managerial or religious elites. They may have also been constructed to align with astronomical observations. Trade with Mexico appears to have declined, but an increased number of trade goods arrived from Pueblo peoples in the north and the east.

Between AD 1350 and 1375, the Hohokam tradition lost vitality and stability, and many of the largest settlements were abandoned. Rapidly changing climatic conditions apparently substantially affected the Hohokam agricultural base and subsequently prevented the cohesion of their large communities. Repeated floods in the middle 14th century significantly deepened the Salt River bed while destroying canal heads, which required their continuous extension upstream. Soon, additional flooding removed irreplaceable segments of these extensions, which effectively rendered hundreds of miles of canals virtually useless. Because of differences in hydrology and geomorphology, these processes had a lesser impact on the irrigation systems used by the Hohokam in the Gila River basin, yet these were abandoned, as well.

Polvoron phase (AD 1350/1375–1450)

This phase is characterized by the widespread use and manufacture of Salado polychrome, with both Gila and Tonto polychromes. After AD 1375, the Hohokam abandoned the villages and canal systems within the lower Salt River basin. This area continued to be occupied, albeit on a far smaller scale. Meanwhile, the very few villages that remained were quite small, and were concentrated along the Gila River, with the notable exception of the lower Queen Creek drainage. Conceptually, this episode is extremely relevant and of great historic importance, as it represents the immediate aftermath of the Hohokam cultural collapse. It represents a critical stage in the ethnogenesis of the modern O'odham.

The Hohokam ceramic tradition

Hohokam ceramics are defined by a distinct Plain, Red, and Decorated buffware tradition. Overall, Hohokam pottery was made from a small, fine clay base connected to a series of coils that were thinned and shaped using the paddle and anvil technique. Hohokam Plain and Red wares were primarily tempered with a variety of materials including micaceous, phyllite, or Squaw Peak schist, as well as granite, quartz, quartzite, and arkosic sands. Analytically, based on the type of temper used, these are classified as to the geographic setting of their manufacture, and are referred to as Gila (Gila River basin), Wingfield (Agua Fria basin, the Northern Periphery, or Lower Verde area), Piestewa Peak (Phoenix metro area north of the Salt River), South Mountain (Phoenix metro area south of the Salt River), or Salt (Salt or Verde River basins) Plain and Red wares. The surfaces of Plain wares were smoothed to some extent and many were polished, and after the vessels were fired, they turned a color that ranged from light or dark brown, gray, to orange. Later, the interiors of bowls were slipped with a black carbonous material. Hohokam Red wares were slipped with an iron-based pigment that turned red after the vessel was fired.

The manufacture of decorated Hohokam pottery was similar to that of the Plain wares. However, the clays tended to be of a finer quality and were tempered with caliche and limited amounts of very finely ground micaceous schist and small particles of vegetive material.

Cultural divisions

Cultural labels such as Hohokam, Ancient Pueblo (Anasazi), Mogollon, or Patayan are used by archaeologists to define cultural differences among prehistoric peoples. Culture names and divisions have been assigned by individuals separated from the cultures by both time and space. Cultural divisions are by nature arbitrary, and are based solely on data available at the time of scholarly analysis and publication. They are subject to change, not only on the basis of new information and discoveries, but also as attitudes and perspectives change within the scientific community. An archaeological division cannot be assumed to correspond to a particular language group or to a political entity such as a "tribe".

When making use of modern cultural divisions in the Southwest, three specific limitations in the current conventions exist:

- Archaeological research focuses on physical remains, the items left behind during people's activities. Scientists are able to examine fragments of pottery vessels, human remains, stone tools. or evidence left from the construction of buildings, but many other aspects of the cultures of prehistoric peoples are not tangible. Languages spoken by these people and their beliefs and behavior are difficult to decipher from the physical materials. Cultural divisions are tools of the modern scientist, so should not be considered similar to divisions or relationships the ancient residents may have recognized. Modern cultures in this region, many of whom claim some of these ancient people as ancestors, contain a striking range of diversity in lifestyle, language, and religious belief. This suggests the ancient people were also more diverse than their material remains may suggest.

- The modern term "style" has a bearing on how material items such as pottery or architecture can be interpreted. Within a people, different ways to accomplish the same goal can be adopted by subsets of the larger group. For example, in modern Western cultures, alternative styles of clothing t characterize older and younger generations. Some cultural differences may be based on linear traditions, on teaching from one generation or "school" to another. Varieties in style may define arbitrary groups within a culture, perhaps identifying social status, gender, clan or guild affiliation, religious belief, or cultural alliances. Variations may also simply reflect the different resources available in given time or area.

- Designating culture groups, such as the Hohokam, tends to create an image of group territories separated by clear-cut boundaries, like modern nation states. These simply did not exist. "Prehistoric people traded, worshipped, and collaborated most often with other nearby groups. Cultural differences should therefore be understood as 'clinal', 'increasing gradually as the distance separating groups also increases.'" [10] Departures from the expected pattern may occur because of unidentifiable social or political situations or because of geographical barriers. In the Southwest, mountain ranges, rivers, and most obviously, the Grand Canyon, can be significant geographic barriers for human communities, likely reducing the frequency of contact with other groups. Current opinion holds that the closer cultural similarity between the Mogollon and Anasazi and their greater differences from the Hohokam culture is due to both the geography and the variety of climate zones in the Southwest.

Major core area Hohokam villages

The true measure of the Hohokam can only be derived from the sum of their material culture. This is best gleaned from a review of their principal population centers, or more appropriately, major villages. Although sharing a common cultural expression, each of these major villages has its own unique history of emergence, growth, and eventual abandonment. Including outlines of archaeological exploration, provided below are brief descriptions of the largest and most important prehistoric villages found within the so-called Hohokam core area.

Snaketown

Snaketown was the archetypical Preclassic period settlement and preeminent community centered within the core of the Hohokam culture area. Today, Snaketown is situated within the Hohokam Pima National Monument, located near Santan, Arizona, which was authorized by Congress on October 21, 1972. Excavations conducted in the 1930s and again in the 1960s revealed that the site was inhabited from about 300 BC to AD 1050. At its height in the early 11th century, Snaketown was the center of both the Hohokam culture and the production of the distinctive Hohokam buff ware. Following the last excavations conducted by Emil Haury, the site was completely recovered with earth, leaving nothing visible above ground.

Overall, Snaketown boasted two ball courts, numerous trash mounds, a small ceremonial mound, a large central plaza, several large community houses, and hundreds of residential pithouses, and may have been home to at least several thousand people. After Snaketown was abandoned, several minor settlements were founded within the general vicinity and continued to be occupied until the early 14th century AD. The Hohokam Pima National Monument is located on Gila River Indian Community (GRIC) land and is under tribal ownership. It covers nearly 1,700 acres (688 ha) (6.9 km²). The GRIC has decided not to open this extremely sensitive prehistoric site to the public.

Grewe-Casa Grande

Altogether, the greater Grewe-Casa Grande Site represented the largest Hohokam community located within the middle Gila River valley. Situated between two primary canals (on the north, Canal Casa Grande and to the south Canal Coolidge), over time, this community was recorded as several separate archaeological sites. These include the Casa Grande, Grewe, Vahki Inn Village, and Horvath sites. Occupied in the Preclassic and Classic periods, each of these sites was composed of between two and 20 large residential areas. Overall, the greater Grewe-Casa Grande archaeological site covered about 900 acres (3.6 km2), centered on State Route 87 and immediately north of the modern city of Coolidge, Arizona.

Most observers are attracted to the four-story great house found near the center of the Casa Grande Ruins National Monument. Akimel O'odham oral tradition records that prior to the arrival of the Sto'am O'odham, or "Coyote People", this massive structure was built by an important personage called Sial Teu-utak Sivan, (Morning-Green Leader) or "Chief Turquoise". In the O'odham language, the great house and the associated prehistoric ruins found north of Coolidge were collectively referred to as Sivan Vah'Ki, literally meaning the "Abandoned House", or "Village of the Ruler", respectively. As Frank Russell recorded in the early 20th century, several O'odham oral traditions note that Sial Teu-utak was an important leader of the Casa Grande community, before the overthrow of the Suwu'Ki O'odham, or "Vulture People". Eusebio Francesco Chini (Father Kino) arrived in the middle Gila River valley in 1694 to find the monumental great house abandoned and already in a state of decay and decomposition. Despite its condition, later Jesuit missionaries and he used the great house to hold Mass, between the late 17th and 18th centuries.

Adolph Bandelier provided one of the first detailed archaeological maps and descriptions of Classic period architecture at the central locus, or Compound A, of the Casa Grande site, in 1884. Jesse Walter Fewkes and Cosmos Mindeleff made further descriptions of this area. Between 1906 and 1912, Fewkes conduced excavations and stabilization of this portion of the site. In 1927, Harold Gladwin excavated stratified tests of several trash mounds at both the Grewe and Casa Grande sites. He also defined and excavated portions of Sacaton 9:6 (GP), an adobe-walled compound situated on the extreme edge of the Casa Grande site, east of State Route 87, near the current entrance to the monument. Relatively large-scale excavations were carried out between 1930 and 1931, by Van Bergen-Los Angeles Museum Expedition under the direction of Arthur Woodward and Irwin Hayden. This project concentrated on a 30-acre (120,000 m2) parcel at the Grewe site, and Compound F located within the northeast corner of the Casa Grande National Monument. Overall, including the recovery of 172 burials and hundreds of thousands of artifacts, about 60 pithouses, numerous pits, 27 adobe pitrooms, and a ballcourt were excavated or tested during the course of this project.

Additional excavations were performed in the southeast corner of the monument by the Civil Works Administration directed by Russell Hastings in 1933 and 1934. The excavation of 15 pithouses, three pits, 32 burials, and portions of four trash mounds demonstrated the presence of significantly large late Preclassic and early Classic period components within the area covered by the monument. Yet, by far the largest and most comprehensive archaeological endeavor was conducted by Northland Research Inc., from 1995 to 1997, on a 13-acre (53,000 m2) parcel within portions of the Casa Grande, Grewe, and Horvath sites that paralleled State Routes 87 and 287. This project was directed by Douglass Craig, and resulted in the identification and/or excavation of 247 pithouses, 24 pitrooms, 866 pits, 11 canal alignments, a ballcourt, and portions of four adobe-walled compounds, as well as the recovery of 158 burials and over 400,000 artifacts.

Based on the results of these projects, the history of the greater Grewe-Casa Grande site can be reconstructed with at least some degree of precision. The genesis of this important village appears to have been associated with several groups of pithouses organized around a series of relatively small, circular plazas. These appear to date to the sixth century AD and were located along and immediately upslope of the Coolidge Canal system. By the eighth century AD, this dispersed hamlet had expanded nearly a kilometer south and developed into a full-fledged village. At this point, the settlement consisted of densely packed yet discrete groups of pithouses clustered around small open courtyards. In turn these structures delineated a large central plaza. Adjoining the plaza was a medium-sized ballcourt, and overall, the village was affiliated with several smaller outlying settlements.

In the 10th century, at least two large secondary villages and about a dozen new hamlets were founded to the west of the main settlement. With the abandonment of Snaketown and the transition from the Preclassic to Classic periods, the greater Grewe-Casa Grande community became one of the largest and most important Hohokam population centers. At its height, the Grewe-Casa Grande village boosted about 100 trash mounds, several hundred residential pithouses, and four or five ballcourts. Regardless of its size, complexity, and significance along the middle Gila River, this settlement never seemed to have attained the status enjoyed by Snaketown, as it pertained to the Hohokam culture, per se. As the western portion of this settlement grew, large sections of the eastern half declined and were abandoned. By AD 1300, the village was composed of about 19 adobe-walled residential compounds, several pitroom clusters, a platform mound, a great house, and numerous trash mounds. With most of the village contained within what is now the Casa Grande Ruins National Monument, after the middle of the 14th century, it began a rapid decline. Around AD 1400 or 1450, the entire settlement was abandoned, except for a low-scale occupation associated with the Polvoron phase.

Today, about 60% of the Grewe-Casa Grande site has been either destroyed due to agricultural and commercial development, excavated, or remains relatively intact buried under fields used to grow cotton. About 40% of this once huge settlement can be found within the Casa Grande Ruins National Monument, which was established as the nation's first archeological reserve in 1892, and declared a national monument in 1918. Visitors can enjoy an interpretative center, walk among the stabilized ruins of Compound A, and closely view the great house, which has been protected since 1932 from the elements by a distinctively modern-looking roof.

Pueblo Grande

Pueblo Grande Museum Archeological Park near central Phoenix contains preserved ruins and artifact exhibits. Archaeological finds have been recorded along the track of the adjacent Valley Metro light-rail construction.

Mesa Grande

The Mesa Grande ruin, located in Mesa, Arizona, represents another large Hohokam village that was occupied both in the Preclassic and Classic periods, from around AD 200 to 1450. Although this settlement appears to have been very important, it has had little archaeological work, other than the mapping and stabilization projects conducted by the Southwest Archaeology Team (SWAT). The SWAT's indispensable volunteer work at the Mesa Grande ruin began in the middle 1990s and continues today.

At its peak in the late Preclassic and early Classic periods, this settlement may have consisted of as many as 20 discrete residential areas and covered several hundred acres. Today, due to massive urban development, the surface remains of the village have been reduced to a small parcel situated immediately west of the Mesa Hospital. Within this plot are the ruins of a large adobe compound and a nine-meter-high, relatively intact platform mound. This is only one of the last three remaining Hohokam platform mounds in the greater Phoenix metro area. This parcel was transferred into public ownership in the mid-1980s, therefore the compound and mound were not destroyed, yet the city of Mesa has yet to fund any property upgrades, with the exception of a new fence. As of August 2007, this important prehistoric ruin remained on the Arizona Preservation Foundation's list of Most Endangered Historic Places due to benign neglect.

Las Colinas and Los Hornos

Located within the modern city of Tempe, Arizona, the Hohokam settlement of Los Hornos (from the Spanish los hornos, meaning 'the ovens') was initially investigated by Frank Cushing in 1887. With urban expansion, additional excavations were conducted in the 1970s, late 1980s, and throughout the 1990s. The results of these comprehensive archaeological projects have documented both a large Preclassic- and Classic-period village organized much the same as Snaketown and Pueblo Grande, respectively, yet on a somewhat smaller scale. Los Hornos appears to have started around AD 400, as a small cluster of rectangular pithouses situated on the extreme western edge of the site, west of Priest Dr and south of US 60.

Over time, the Los Hornos settlement expanded along a series of large secondary canals to the east and southeast. At the height of the Preclassic occupation in the Sacaton phase, which was contemporary with the zenith of Snaketown, this settlement had one large ball court, a large central plaza, several formal cremation cemeteries, numerous trash mounds, and several hundred residential pithouses. The detailed excavation of 50 Preclassic period pithouses in the area located immediately south of US 60 and east of Priest Dr, provided invaluable information concerning residential architecture and the functional use of interior space. Additional information concerning the Archaeological Consulting Services Ltd. excavation of a Preclassic occupation at Los Hornos can be found at the following site.[11]

After a short period of population loss and community reorganization in the late 11th and early 12th centuries AD, Los Hornos continued to shift east and south in the Classic period. This large village appears to have recovered somewhat and again became an important settlement late in the Soho or early in the Civano phases, from AD 1277 to 1325. At this time, Los Hornos, now centered on Hardy Dr south of US 60 and north of Baseline Road, consisted of about 15 residential compounds, a large central plaza, a large rectangular platform mound with an associated compound, several large trash mounds, and numerous borrow pits and inhumation and cremation cemeteries.

Prior to the middle of the 14th century AD, with the rise of Los Muertos located several miles to the southeast, the Los Hornos community appears to have spiraled into a precipitous decline. Although greatly reduced in scale and importance, the settlement continued to be occupied until it was effectively abandoned between AD 1400 and 1450, as was much of the Lower Salt River basin. Today, much of the Los Hornos village has been destroyed due to modern transportation, residential, and commercial development, or has been excavated. The only surface vestiges of this once significant Hohokam settlement are the remains of several low trash mounds found in the Old Guadalupe Village Cemetery.

Hohokam archaeological sites

The following Hohokam archaeological sites and museums are open to the public, except for Hohokam Pima National Monument.

- Casa Grande Ruins National Monument, Coolidge, Arizona. Casa Grande Ruins National Monument

- Hohokam Pima National Monument (Snaketown), Gila River Indian Reservation (closed to public).[12]

- Indian Mesa, Peoria, Arizona

- Mesa Grande Ruins, Mesa, Arizona.[13]

- Painted Rock Petroglyph Site, Theba, Arizona

- Park of the Canals, Mesa, Arizona. [14]

- Pueblo Grande Museum Archeological Park, Phoenix, Arizona.[15]

- Sears-Kay Ruin - Hohokam Fort on top of a foothill in Carefree, Arizona.

- White Tank Mountain Regional Park, White Tank Mountains

Gallery

| Images related to Hohokam culture | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

See also

- Agriculture in the prehistoric Southwest

- Ancient Pueblo Peoples

- Oasisamerica cultures

- List of dwellings of Pueblo peoples

References

- ↑ Powell, James Lawrence (2008). Dead pool: Lake Powell, global warming, and the future of water in the West. University of California Press. p. 32. ISBN 0-520-25477-5.

- ↑ https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/Hohokam

- ↑ -wni hohokam

- 1 2 3 "The Hohokam". Arizona Museum of Natural History, City of Mesa. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- ↑ 2007-036 General COP Treatment Plan; Pueblo Grande Museum Project 2007-95; City of Phoenix Project No. ST87350010; p. 9 Cultural Context

- ↑ Haury, Emil W Snaketown: 1964-1965, Kiva Vol. 31, No. 1. Maney Publishing on behalf of the Arizona Archaeological and Historical Society, Oct., 1965, p. 8.

- ↑ Powell 2008, pp. 32, 33.

- ↑ "Lake Pleasant (Images of America)", Author: Gerard Giordano; Page: 13; Arcadia Publishing; ISBN 978-0738571768

- ↑ Fish, Suzanne K. "Hohokam Impacts on Sonoran Desert Environment" in Imperfect Balance: Landscape Transformations in the Precolumbian Americas. ed by David L. Lentz. New York: Columbia U Press, 2000, pp.251-280

- ↑ (Plog, p. 72)

- ↑ "Virtual Hohokam Chronology Building and Research: Los Hornos". mc.maricopa.edu. Retrieved 2008-07-30.

- ↑ Hohokam Pima National Monument

- ↑ Arizona Museum of Natural History: Mesa Grande Ruins — the ruins are under direction of the museum.

- ↑ Mesa Parks Dept: Park of the Canals

- ↑ Phoenix Parks Dept: Pueblo Grande Museum Archeological Park — Pueblo Grande Ruin and Irrigation Sites.

Further reading

- Gladwin, Harold S., 1965 Excavations at Snaketown, Material Culture.

- Haury, Emil, 1978 The Hohokam: Desert Farmers and Craftsmen.

- Chenault, Mark, Rick Ahlstrom, and Tom Motsinger, 1993 In the Shadow of South Mountain: The Pre-Classic Hohokam of La Ciudad de los Hornos", Part I and II.

- Craig, Douglas B., 2001 The Grewe Archaeological Research Project, Volume 1: Project Background and Feature Descriptions.

- Crown, Patrica L. and Judge, James W, editors. Chaco & Hohokam: Prehistoric Regional Systems in the American Southwest. School of American Research Press, Sante Fe, New Mexico, 1991. ISBN 0-933452-76-4.

- Russell, Frank, 2006 (reprint), The Pima Indians.

- Clemensen, A., 1992 Casa Grande Ruins National Monument, Arizona: A Centennial History of the First Prehistoric Reserve.

- Plog, Stephen. Ancient Peoples of the American Southwest. Thames and Hudson, London, England, 1997. ISBN 0-500-27939-X.

- Seymour, Deni J., 2007a "A Syndetic Approach to Identification of the Historic Mission Site of San Cayetano Del Tumacácori", International Journal of Historical Archaeology, Vol. 11(3):269–296. http://www.springerlink.com/content/w43p168015123202/fulltext.html

- Seymour, Deni J., 2007b "Delicate Diplomacy on a Restless Frontier: Seventeenth-Century Sobaipuri Social And Economic Relations in Northwestern New Spain, Part I". New Mexico Historical Review, Volume 82, No. 4.

- Seymour, Deni J., 2008a "Delicate Diplomacy on a Restless Frontier: Seventeenth-Century Sobaipuri Social And Economic Relations in Northwestern New Spain, Part II", New Mexico Historical Review, Volume 83, No. 2.

- Wilcox, David R., C. Sternberg, and T. R. McGuire. Snaketown Revisited. Arizona State Museum Archaeological Series 155, 1981, University of Arizona.

- Wilcox, David R., and C. Sternberg. Hohokam Ballcourts and Their Interpretation. Arizona State Museum Archaeological Series 160, 1983, University of Arizona.

- Wood, J. Scott 1987 "Checklist of Pottery Types for the Tonto National Forest", The Arizona Archaeologist 21, Arizona Archaeological Society.

- Lekson, Stephen H., 2008 A History of the Ancient Southwest. School for Advanced Research Press, Santa Fe.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hohokam. |

- University of Arizona: "Hohokam Indians of the Tucson Basin" — an online book.

- Encyclopædia Britannica: "Hohokam Culture"

- National Park Service: Casa Grande Ruins National Monument homepage

- National Park Service: Hohokam Pima National Monument

- Tucsoncitizen.com: "Hohokam stargazer may have recorded 1006 supernova"

- Skytonight.com: "Experts question Hohokam "supernova" interpretation"