HIV-1 protease

| HIV-1 Protease (Retropepsin) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

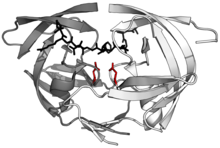

HIV-1 protease dimer in white and grey, with peptide substrate in black and active site aspartate side chains in red. (PDB: 1KJF) | |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| EC number | 3.4.23.16 | ||||||||

| CAS number | 144114-21-6 | ||||||||

| Databases | |||||||||

| IntEnz | IntEnz view | ||||||||

| BRENDA | BRENDA entry | ||||||||

| ExPASy | NiceZyme view | ||||||||

| KEGG | KEGG entry | ||||||||

| MetaCyc | metabolic pathway | ||||||||

| PRIAM | profile | ||||||||

| PDB structures | RCSB PDB PDBe PDBsum | ||||||||

| Gene Ontology | AmiGO / EGO | ||||||||

| |||||||||

HIV-1 protease is a retroviral aspartyl protease (retropepsin) that is essential for the life-cycle of HIV, the retrovirus that causes AIDS.[1][2] HIV protease cleaves newly synthesized polyproteins (namely, Gag and Gag-Pol[3]) at the appropriate places to create the mature protein components of an infectious HIV virion. Without effective HIV protease, HIV virions remain uninfectious.[4][5] Thus, mutation of HIV protease's active site or inhibition of its activity disrupts HIV’s ability to replicate and infect additional cells,[6] making HIV protease inhibition the subject of considerable pharmaceutical research. [7]

Structure and function

HIV protease's protein structure has been investigated using X-ray crystallography. It exists as a homodimer, with each subunit made up of 99 amino acids.[1]

The active site lies between the identical subunits and has the characteristic Asp-Thr-Gly (Asp25, Thr26 and Gly27) sequence common to aspartic proteases. The two Asp25 residues (one from each chain) act as the catalytic residues. According to the mechanism for HIV protease protein cleavage proposed by Mariusz Jaskolski and colleagues, water acts as a nucleophile, which acts in simultaneous conjunction with a well-placed aspartic acid to hydrolyze the scissile peptide bond.[9] Additionally, HIV protease has two molecular "flaps" which move a distance of up to 7 Å when the enzyme becomes associated with a substrate.[10]

HIV-1 protease as a drug target

With its integral role in HIV replication, HIV protease has been a prime target for drug therapy. HIV protease inhibitors work by specifically binding to the active site by mimicking the tetrahedral intermediate of its substrate and essentially becoming “stuck,” disabling the enzyme. After assembly and budding, viral particles lacking active protease cannot mature into infectious virions. Several protease inhibitors have been licensed for HIV therapy.[11]

However, due to the high mutation rates of retroviruses, and considering that changes to a few amino acids within HIV protease can render it much less visible to an inhibitor, the active site of this enzyme can change rapidly when under the selective pressure of replication-inhibiting drugs.[12]

One approach to minimizing the development of drug-resistance in HIV is to administer a combination of drugs which inhibit several key aspects of the HIV replication cycle simultaneously, rather than one drug at a time. Other drug therapy targets include reverse transcriptase, virus attachment, membrane fusion, cDNA integration and virion assembly.[13][14]

See also

External links

- The MEROPS online database for peptidases and their inhibitors: A02.001

- Proteopedia HIV-1_protease - the HIV-1 protease structure in interactive 3D

- HIV-1 Protease at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

References

- 1 2 Davies DR (1990). "The structure and function of the aspartic proteinases". Annu Rev Biophys Biophys Chem. 19 (1): 189–215. PMID 2194475. doi:10.1146/annurev.bb.19.060190.001201.

- ↑ Brik A, Wong CH (January 2003). "HIV-1 protease: mechanism and drug discovery". Org. Biomol. Chem. 1 (1): 5–14. PMID 12929379. doi:10.1039/b208248a.

- ↑ Huang, X; Britto, MD; Kear-Scott, JL; Boone, CD; Rocca, JR; Simmerling, C; Mckenna, R; Bieri, M; Gooley, PR; Dunn, BM; Fanucci, GE (13 June 2014). "The role of select subtype polymorphisms on HIV-1 protease conformational sampling and dynamics.". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 289 (24): 17203–14. PMC 4059161

. PMID 24742668. doi:10.1074/jbc.M114.571836.

. PMID 24742668. doi:10.1074/jbc.M114.571836. - ↑ Kräusslich HG, Ingraham RH, Skoog MT, Wimmer E, Pallai PV, Carter CA (February 1989). "Activity of purified biosynthetic proteinase of human immunodeficiency virus on natural substrates and synthetic peptides". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 86 (3): 807–11. PMC 286566

. PMID 2644644. doi:10.1073/pnas.86.3.807.

. PMID 2644644. doi:10.1073/pnas.86.3.807. - ↑ Kohl NE, Emini EA, Schleif WA, et al. (July 1988). "Active human immunodeficiency virus protease is required for viral infectivity". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 85 (13): 4686–90. PMC 280500

. PMID 3290901. doi:10.1073/pnas.85.13.4686.

. PMID 3290901. doi:10.1073/pnas.85.13.4686. - ↑ Seelmeier S, Schmidt H, Turk V, von der Helm K (September 1988). "Human immunodeficiency virus has an aspartic-type protease that can be inhibited by pepstatin A". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 85 (18): 6612–6. PMC 282027

. PMID 3045820. doi:10.1073/pnas.85.18.6612.

. PMID 3045820. doi:10.1073/pnas.85.18.6612. - ↑ McPhee F, Good AC, Kuntz ID, Craik CS (October 1996). "Engineering human immunodeficiency virus 1 protease heterodimers as macromolecular inhibitors of viral maturation". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93 (21): 11477–81. PMC 56635

. PMID 8876160. doi:10.1073/pnas.93.21.11477.

. PMID 8876160. doi:10.1073/pnas.93.21.11477. - ↑ Perryman AL, Lin JH, McCammon JA (April 2004). "HIV-1 protease molecular dynamics of a wild-type and of the V82F/I84V mutant: possible contributions to drug resistance and a potential new target site for drugs" (PDF). Protein Sci. 13 (4): 1108–23. PMC 2280056

. PMID 15044738. doi:10.1110/ps.03468904. Retrieved 2008-06-27.

. PMID 15044738. doi:10.1110/ps.03468904. Retrieved 2008-06-27. - ↑ Jaskólski M, Tomasselli AG, Sawyer TK, Staples DG, Heinrikson RL, Schneider J, Kent SB, Wlodawer A (February 1991). "Structure at 2.5-A resolution of chemically synthesized human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease complexed with a hydroxyethylene-based inhibitor". Biochemistry. 30 (6): 1600–9. PMID 1993177. doi:10.1021/bi00220a023.

- ↑ Miller M, Schneider J, Sathyanarayana BK, Toth MV, Marshall GR, Clawson L, Selk L, Kent SB, Wlodawer A (December 1989). "Structure of complex of synthetic HIV-1 protease with a substrate-based inhibitor at 2.3 A resolution". Science. 246 (4934): 1149–52. PMID 2686029. doi:10.1126/science.2686029.

- ↑ H.P. Rang (2007). Rang and Dale's pharmacology (6th ed.). Philadelphia, Pa., U.S.A.: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. ISBN 9780808923541.

- ↑ Watkins T, Resch W, Irlbeck D, Swanstrom R (February 2003). "Selection of high-level resistance to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease inhibitors". Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47 (2): 759–69. PMC 151730

. PMID 12543689. doi:10.1128/AAC.47.2.759-769.2003.

. PMID 12543689. doi:10.1128/AAC.47.2.759-769.2003. - ↑ Moore JP, Stevenson M (October 2000). "New targets for inhibitors of HIV-1 replication". Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 1 (1): 40–9. PMID 11413488. doi:10.1038/35036060.

- ↑ De Clercq E (December 2007). "The design of drugs for HIV and HCV". Nat Rev Drug Discov. 6 (12): 1001–18. PMID 18049474. doi:10.1038/nrd2424.