History of the regional distinctions of Spain

For many years the Spanish monarchy and the dictatorships which followed—Primo de Rivera and Franco—maintained the position that Spain was a unified nation, the legacy of the Roman province, Hispania. In reality, Spain (formerly known as the Spains) is and has long been a cluster of different territories with their own systems. Currently, Spain is divided into eighteen autonomous entities, which are themselves composed of fifty provinces. Seven of those eighteen autonomous entities are officially designated as nationalities, while the rest are defined as regions, historical regions, communities and historical communities. There are many proponents of this confederacy, however it does carry certain historical problems. Just as neither modern nor historical Spain were a single unit, the modern divisions also do not really work in the past.[1][2] Nonetheless, modern Spain is more easily understood when one first understands the differences which underlie its current divisions.

A brief history of Spain as a whole

The most relevant part of Spain's early history is that the whole Iberian Peninsula became part of the Roman Empire. The Romans, who divided the peninsula into different provinces, introduced the Latin language, Roman law, and Christianity to the majority of the peninsula, were succeeded by a couple different Germanic tribes. The most significant of these was the Visigoths, who attempted to unify the disparate parts of Iberia, focusing on the Roman legacy, especially the Roman law.[3][4] 711AD marks the beginning of the Moorish period. The vast majority of Iberia came under Islamic control fairly quickly, and gradually receded over time. Over the next couple hundred years, the rulers of Muslim Spain (that is, the still largely Christian part of the peninsula which had Muslim rulers), especially the Caliphate of Cordoba, were consolidating power and patronizing the arts and sciences, as well as experiencing relative religious tolerance. In the mountainous, rural northern regions to the north, the Christian rulers were regaining their footing, despite numerous internal conflicts. The next couple hundred years can largely be described as a period of intermittent aggression balanced with wary tolerance. The Christian kingdoms gradually expanded at the expense of the Caliphate of Cordoba and sometimes of each other in a process known as the Reconquista. With the disintegration of the Caliphate into the “Taifa States,” the Christian kingdoms were able to more easily expand by means of shifting alliances. A couple successive fundamentalist Islamic regimes (primarily the Almoravids followed by the Almohads) invaded from North Africa and imposed unity on the Taifa kingdoms at the expense of tolerance and intellectual livelihood. The thirteenth century saw a drastic expansion in which the Christian kingdoms approximately doubled their territory, leaving Granada as the only independent Muslim state, albeit a highly bullied one.[5] That was finally conquered by the Kingdom of Castile in 1492. Just as Christians remained in Moorish Spain after that conquest, so too did Muslims and Moorish culture remain after the Christian conquest.[6] Though there are other aspects of history from that time and later, those are best left to other portions of the article or to other articles altogether.

Macro differences: North, Centre and South

Overall, the different Spanish territories follow just a few basic patterns of how they identify themselves as distinct from the rest of Spain. In the north: Galicia, Castile, León, Asturias, the Basque Country and Navarre; and the east: Aragon, Catalonia, and Valencia distinguish themselves through claims of historical independence and, often, the presence of a native minority language. Many of these areas also claim that they were never completely conquered by the Muslims, while the rest of Iberia was. In the south, however, Andalusia, and to a lesser extent Murcia and Extremadura, claim a unique regional identity through either more recent Muslim occupation or through the longer-lasting presence of Morisco culture. Much as the northern territories identify with Christian kingdoms from the early Reconquista, before dynastic unions linked the provinces, the southern realms take into consideration either the independent Muslim kingdoms from before their absorption into Christian crowns or focus on the cultural centers that had once been prominent. In central Spain, entities have neither historical languages nor independent historical kingdoms to look back on, however these areas have identities directly connected to the Kingdom of Castile. Clearly, each area in Spain has its own specifics, and there are even differences within territories. However, most parts of the peninsula do fall into one of these three categories at any point from the Reconquista onwards.

Special cases

For the most part, each of the present autonomous communities in Spain can be treated individually, with only minor territorial differences as one looks into the past. There are some instances in which certain groups or divisions need to be indicated. First, the autonomous communities which made up the former Crown of Aragon (Aragon, Catalonia, Valencia, and the Balearic Islands) can be treated with slightly more unity when dealing with the past than when dealing with the present.[7] However, over the past century or so, the notion of the “Catalan Countries” has taken hold. The concepts of the Crown of Aragon and the Catalan Countries will be dealt with more specifically in their own section, and, though they cover similar territories, they occupy different places in time and therefore need to be treated separately. Another significant large former entity, already alluded to, is that of Castile proper. Though the Crown of Castile encompassed many of these areas for a long time, New Castile (Castile-La Mancha and Madrid, and Old Castile (eastern Castile and León) are the only parts of the Crown of Castile which can be considered integral to nuclear Castile and which share many qualities. The last key super-region is that of the Basque Country in its larger sense (composed of The Autonomous Community of the Basque Country, Navarre, and the Northern Basque Country which is in France. Those territories share certain similar issues and therefore can be grouped together. However, the different parts of the Basque Country as a whole are fairly divided, and therefore should still be treated separately, even while grouped together.

There are also some specific divisions within a couple of the modern autonomous communities. Andalusia is the most populous and second largest autonomous community in Spain, and has a great deal of diversity. Though it functions as one administrative unit, Andalusia should more properly be considered a collection of distinct regions.[8] Nearly all of the autonomous communities are, in fact, such collections, but Andalusia's regions require a bit more specific attention. The other real subdivision which is necessary is to divide Castile and León into Old Castile and León, as they have historically different languages and kingdoms, as well as somewhat different terrain.

There are also some territories which do not clearly fit into any of these. In general, they are somewhat related to Castile, yet have chosen to remain independent.

One final concession is that, though long a separate country, Portugal can also briefly be included. A period of about 60 years saw Portugal united with Spain because of the failure of the royal house to produce future monarchs. The Portuguese can therefore be briefly included, to represent those 60 years and to provide a counter-example to other parts of Spain which desired to emulate the Portuguese, though they do not have their own section in this article yet.[9]

Crown of Aragon

By the time of the dynastic union between Ferdinand and Isabella, the Crown of Aragon encompassed many different territories, including ones in other parts of the Mediterranean Sea, though only four remain within Spain's borders now. At the time of the union, and long afterwards, those territories were known as the Kingdom of Aragon, the Principality of Catalonia, the Kingdom of Valencia, and the Kingdom of Majorca. Despite all being under the same crown, each kingdom effectively had its own distinct government.[10] The structure of the government in each of these places played a significant, albeit not an exclusive, role in determining how people of these locations thought about themselves with relation to others who shared their peninsula.

In order to understand this part of Spain in later times, one must first look at how it was organized under the Crown of Aragon. There are two particularly significant traits of the Crown of Aragon: limited monarchy and a federalist structure.[11] The monarchy was limited by some of the earliest constitutions in Europe. In the federalist system each region was essentially treated as a separate country with separate laws, though united by one king. Each kingdom jealously guarded its traditional laws, which were guaranteed respect by the monarchy. A key component of these rights was the parliament, which each territory had. These parliaments claimed representative authority for the people of their region, initiated new legislation (though the king retained veto power), and needed to approve any expenditures by the crown. These powers of the different parliaments, in addition to other limitations on monarchial authority as well as significant divisions between the territory, meant that the king always faced a great deal of negotiation and compromise in order to achieve any of his own goals. Due to the nature of the dynastic union of Aragon and Castile, through Ferdinand and Isabella, these kingdoms retained independence in custom, name, law, and even governmental process. Their strong independence under the Aragonese crown and the persistence of their local rights and systems as a part of Spain created a sense of independent identity which was hard to quench and which easily reacted to potential threats. On the other hand, the Spanish leaders, whether monarchs, government officials, or 20th century dictators, constantly felt that the peoples of these regions were threatening the perceived unity of Spain through sheer stubbornness and continuously tried to bring them closer to the center.[12] Those efforts were rightly perceived as threats to the liberty of the inhabitants of the former Crown of Aragon and did little to make those inhabitants want to give up their local identity in favor of a larger Spanish Identity which was, in effect, a Castilian identity.

Catalan Countries

Over the past few decades, a region known as the Catalan Countries (Països Catalans) by Catalan nationalism has developed. This is the idea that Catalonia, Valencia, the Balearic Islands and a few other places in Spain and in other European countries are united by the fact that they share Catalan as a historic language. Though this is a convenient way of expanding perceived Catalan importance and does impact the identity of the people who live in those areas, this multi-regional identity is fairly recent, and is not a good indicator of older stages of regional identity. Nonetheless, a feature common to the Catalan Countries within Spain, even in the past, is that they are separated from the rest of Spain by a significant language barrier.

Catalonia

One of the most troubling provinces in the Spanish Empire, according to the central authorities (or one of the provinces to which the Empire was the most troubling, according to the Catalans), Catalonia's identity actually derives from before it was a part of the Crown of Aragon. Largely free of Muslim occupation, Catalonia long had closer ties to France and areas other than in Iberia. Briefly part of Charlemagne’s empire, the Catalan counties broke away when Charlemagne proved unable to successfully defend them.[13] Though literacy was restricted to relatively few, as in the rest of Europe, medieval Catalonia developed a strong literary tradition, especially represented by the Jocs Florals, a form of poetry contest. Further, the principalities which were slowly consolidating around Barcelona formed fairly strong populist tendencies. Though primarily supported by the nobles and upper merchant classes, Catalonia developed one of the first constitutional monarchies in Europe, setting the stage for later constitutional and republican movements in the region. In another example of unusually strong support for the common people, the monarchy often supported the peasants in Catalonia in their struggle with the nobles who attempted to control the government and the peasants. The union with Aragon and the key role of the Corts Catalanes, as mentioned before, in addition to the Generalitat of Catalonia, strengthened this belief in constitutional restraints on monarchy and in representative government (even if that government was selectively representative).

While it was a part of the Spanish Empire, several factors strengthened the Catalans’ sense of separation from the rest of the peninsula. At this time, the most important was conflict with the centralizing tendencies of the government, though the increasing importance of the Atlantic trade also economy also strengthened that separation. More importantly, perpetual pestering pertaining pecuniary provisions, perceived as presumptuous political provocation, proved positively painful, preventing provincial pleasure.[14] This came to a head in 1640 when the Count-Duke of Olivares stationed royal troops in the region at the expense of the local population, sparking the first failed regional revolt. This revolt had broad support, though the upper classes were eventually alienated by popular desire to reform the whole system.

Nevertheless, during the War of the Spanish Succession, Catalonia was divided as well as Castile in regards to who should succeed the late Charles II, but its institutions, the Diputació del General and the Consell de Cent, spearheaded by part of the nobility, did support the Austrian candidate, Charles with the support of numerous other European countries (but not France). One provision of the treaty which ended the war was that Spain would lose its other European territories. Despite an official peace, Catalonia continued fighting alone. In response to that independent feeling, though, Philip V outlawed many Catalan political and cultural institutions, and castilian was introduced as official language to be used in government and courts.[15]

Later on, Catalonia, especially Barcelona, was the first Spanish subdivision to industrialize in Spain (followed by Bilbao in the Basque Country). This early industrialization and the associated new economic problems associate with it led to even more of a break with the central government and culture.[16] The Renaixença, a Catalan literary revival, was partly in response to this industrialization and was important in the development of modern Catalan identity.[17] The Catalans also developed a distinct form of modernism in the couple decades around the turn of the nineteenth century. This emergence of a distinctive, modern Catalan cultural heritage further reinforced Catalan identity and helped lead to some feelings of separatism where are no longer as prominent as before.

Valencia

The second main entity included in the Catalan Countries is Valencia. This strip of land along the eastern coast of Spain is different from other parts of the country in that it has a shared history as being a Catalan-speaking former member of the Crown of Aragon and has a fairly strong connection with Moorish and Morisco culture. The Kingdom of Valencia became a part of the Crown of Aragon when it was conquered from the Moors in the thirteenth century. The Crown of Aragon instituted a form of independent government in Valencia similar to what already existed in the Kingdom of Aragon and the Principality of Catalonia, leading to that region having a sense of independence similar to the other regions of the Aragonese Crown. After that conquest, an increasing number of Catalan speakers moved into the area, ultimately becoming the basis for its inclusion in the Catalan Countries. Nonetheless, Valencia retained a high Muslim, Arabic-speaking population for long after the conquest by a Christian ruler. This population gave Valencia a strong bi-religious, bi-lingual character for the next couple centuries.[18] Even so, the Muslims often felt oppressed by their Christian rulers, with good reason. Common Christians felt betrayed by their rulers and threatened by the Muslims. Those feelings were part of what led to the Revolt of the Germanías. This revolt was particular to one region and did attempt to overturn the social order, but it did not call upon regional identity even though it later became part of the regional historical narrative.[19] Ultimately, identity as a Valencian was restricted to those who could participate in the system of power, namely the nobles and a highly limited number of wealthy merchants.

Like the other members of the Crown of Aragon, Valencia remained an independent state under the Crown of Castile, governed by the Corts Valencianes and the Furs of Valencia. The expulsion of the Muslims from Spain in 1501 left a dent in the population of Valencia. However, many of the Muslims preferred to nominally accept Christianity, thereby becoming Moriscos. Though there were Moriscos in many parts of Spain, those in Valencia were more tied to the land than elsewhere. They were also particularly involved in construction and beautification in the employ of the rulers. Valencia from this period is marked by a distinctive form of Morisco architecture and many gardens.[20] The final expulsion of the Moriscos from Valencia in 1609 marked the end of this era, yet the Morisco influence and many cultural aspects lived on in the Christian population. Though Valencia never tried to officially break with Spain and had generally closer ties with the rest of Spain than did Catalonia (including a greater Castilian-speaking population), it nevertheless continued to assert its independent nature within the political system. That tended to be merely political, however, and most Valencians were not particularly interested in whether they were Valencian, Catalan, Castilian, or Spanish. Even that political independence was fairly minor, especially when compared to Aragon and Catalonia. Independent Valencian identity remained either unimportant or hidden for political reasons until the late 20th century. At that point, it began to face the problem of distinguishing itself from Spain as Catalan-speaking with a Catalan heritage and of distinguishing itself from Catalonia as Valencian-speaking with a uniquely Valenican heritage.

Balearic Islands

The Balearic Islands do not have as strong ideological differences as the above groups. Their role in Aragonese government was minimal, as they were not an important territory. Like the Valencians, inhabitants of the Balearic Islands speak dialects of Catalan which they prefer to consider as separate languages. Their primary basis for regional identity does not extend to the fact that they come from the Balearic Islands as much as it is tied to the specific island on which they live. Each island has its own dialect and its own identity as an individual island. There are those who consider themselves as part of the larger Catalan-speaking territory in the larger cities as well as Castilians who prefer to claim a relationship more as part of Spain. One significant aspect of the Balearic Islands, as well as many places in Valencia, is that there are large numbers of northern tourists and retired people. These largely accept the local identity, tending towards the more-inclusive Catalan-speaking identity, as that is easier to acquire than that of a particular island.[21]

Aragon

Though Aragon is a former member of the Crown of Aragon, in modern times it tends to operate slightly more like some of the other northern regions. Nonetheless, Aragonese identity has a long history. One of the mountainous regions which avoided complete Muslim domination, Aragon was initially composed of tiny mountain duchys. The County of Aragon soon broke away from Navarre, eventually dominating the other mountain duchys. Eventually, Aragon joined the Principality of Catalonia, and the subsequent history of the Crown of Aragon has largely been told already, or can be found elsewhere. Aragon itself, despite providing the name of the Aragonese Empire, was the least important Iberian member.[22] Most of the region was made of mountains or desert, and its inland location favored Catalonia for Mediterranean trade. After the union with the Kingdom of Castile, Aragon, like Catalonia, strongly maintained its independence. One example from the life of Philip II shows how he and all of his Castilian officials had a ceremony to pass the border in which they celebrated, but all officials also had to lay down their symbols of authority because they were entering a different kingdom.[23] A more significant example is that there was a significant revolt in Aragon in 1591-1592 over the role of their fueros.[24] This was not nationalist in the modern sense, though it did play to the idea of national and regional rights and independence.

Like Valencia, Aragon had a large number of Muslims, and later Moriscos, living in its southern plains. Though this is a key ingredient of Aragon at the time, Aragon is not known for as extensive of a Morisco influence as Valencia, though it too retained significant Moorish influence after the expulsion. As the Moriscos primarily lived in the Ebro valley in the south, rather than the mountainous north, this Morisco influence was not as evenly spread as in Valencia.[25] Additionally, Aragon’s landscape did not lend itself to Moorish gardens, as in Valencia, nor were the Moriscos there as involved in building projects so as to leave their architectural mark.[26]

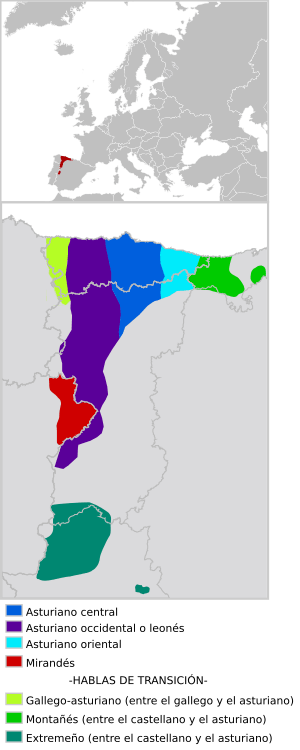

In more modern times, Aragon functions more like some of the other northern territories. It has its own language, Aragonese, though that is primarily spoken in the mountainous north while Castillian is spoken in the southern two-thirds and Catalan is spoken along the eastern strip. Because of the prevalence of Castilian and the presence of Catalan, the language does not play as large of a role in Aragonese identity as in some other locations. Rather, Aragon hearkens back to its role as an independent state with its own parliament under the Aragonese Crown.

Basque Country

Basque Country refers to a region crossing the border between Spain and France in which the Basque people live. Within Spain, the Basque Country is divided into Navarre and the autonomous community of the Basque Country. The basis for the modern expression of Basque identity in both of these regions, as well as in France, derives from similar sources, though there are a few differences between regions. The single most significant aspect of Basque identity is their unique language (Basque: Euskara) which is not related to any known language. Records of people and place names from Roman times indicate that the Basques occupied an area somewhat larger than what they currently inhabit. As national identity and independence often makes claims based on historical presence, the evidence from the Romans about the Basques gives them a strong position. From this, they can claim that the Basque homeland has been occupied by the Basques longer than any other land in western Europe has been inhabited by their people (with the main exceptions of Italy and perhaps the Celtic-speaking areas), and especially longer than anywhere in France or Spain. This is at least what Sabino Arana, the traditional founder of Basque Nationalism, claimed.[27] It also seems that, because of their highly different language, the Basques were aware of their uniqueness as a people from a fairly early time compared to other Iberian peoples.

Beginning with the Muslim conquest of most of the peninsula, the Basques begin to have similar claims to the other regions of Northern Iberia. Like the other regions, they remained independent, Christian kingdoms, though they did not participate as much in the Reconquista as the other regions did. Another key feature of this time is that the Basques occupied a central region of Christian Iberia, lending them special importance.[28] This centrality, though no longer important in Basque identity, is reflected in many traditional “Spanish” names and in the Castilian language, which linguists argue originated as a trade language between the Romance- and Basque-speaking populations of central north Spain during the early Reconquista.

Basque Country (autonomous community)

Despite such shared history and shared sources of a modern Basque identity, the larger Basque region has always been more separated than united. As already mentioned, three of the seven Basque provinces are in France rather than Spain, and Navarre, one of the four in Spain, chooses to remain independent from the autonomous community of the Basque Country. That autonomous community therefore only refers to three of the Basque provinces. Those three provinces have been part of the Castilian Crown the longest, yet continued to assert their own identity. A key point of dissension between the Basques and the Castilian monarch was the role of their regional rights (Castilian: fueros vascos, Basque: euskal foruak). For the Basques, each region defined its relationship to the crown through these fueros and the fueros were part of what distinguished one region from another. That is, they were Basques because of their inherited rights and obligations and not as much because of their language, specific place of birth, or any bureaucratic distinction.

One aspect of the Basque Country as a whole, but particularly applies here, is that though they share a common identity through speaking their own distinct language, the different dialects of Basque sometimes vary so greatly as to be nearly mutually unintelligible. For many years the great difference within the one language served to fragment the overall region in the manner that it is still highly fragmented. However, what served to separate the Basques from each other also set them apart from Romance-speakers and created strong ties to the local community or the immediate region. Therefore, for centuries a Basque was not a Basque, but someone from Araba, Gipuzkoa, Bizkaia, etc. Only within the past 150 years or so have people referred to the “Basque Nation” (Basque: Euskal Herria, Euskadi).

Navarre

While Navarre does carry some of the linguistic aspects and has its own set of fueros, it is distinct. The southern half of Navarre is almost exclusively inhabited by speakers of Castilian. In contrast with the other Basque provinces, Navarre remained an independent country until it was militarily conquered by Castile in the early 16th century. After this conquest, the Navarrese, like the Basque Provinces, were granted the respect of their fueros, and those fueros were maintained even through the Franco period. Much like the components of the former Crown of Aragon, Navarre retained a sense of its origin as a separate country. However, despite its military conquest rather than a dynastic union, and despite a few initial popular revolts against Castile, Navarre suffered less separatism than places like Catalonia. It is likely, Navarrese foral rights were more easily reconcilable to a Castilian monarchial system than the Catalan constitutional rights. It also helped quite a bit that Philip V permitted greater regional independence as a reward for fighting on his side during the War of the Spanish Succession while he punished Catalonia's rebellion, a situation which was later repeated following Navarre's support of Franco in the Spanish Civil War.[29] In addition, Navarre was a less economically important region, and therefore suffered less pressure when the crown needed resources.

Northernwestern territories

As has already been mentioned, the northern territories for the most part share a similar pattern of identity development. Each region has its own language or distinct dialect, most of which derive from different dialects from the early Reconquista. Most of these regions were largely independent of Muslim rule and continuously shifted between Christian kings during the Reconquista, sometimes being split between three or four kingdoms, but at other times being entirely united. Eventually, the Christian territory expanded far enough for Portugal to break from Galicia, which shortly afterwards united with León. After that, the Reconquista in all parts except for Valencia was carried out by Portugal, León, and Castile. In the beginning of the 14th century, after the major Christian expansion in the preceding century, León united with Castile. Like the other kingdoms later, León initially retained its own legal system despite being ruled by Castile. From this point on, all of the northern territories west of Navarre were under the Castilian Crown, which attempted to centralize more and more. Despite that increasing centralization, which united some of the judicial and governmental structures with those of Castile over time and which promoted increased castilianization of the upper classes, the regions in northern Spain still retained and recreated their own regional identities.

Galicia

Galicia was its own kingdom at one point, yet that factored relatively little in Galician identity. First, Galicia’s union with León, and later Galicia-Asturias-León’s union with Castile, was so early that it had more identity as part of a larger unit than by itself. In modern times, a key part of Galician identity is its language. Galician is more similar to Portuguese than Castilian, and they similarly perceive greater unity with Portugal than Castile (There have actually existed a couple movements designed to unite Galicia with Portugal instead of Spain in order to help preserve its linguistic identity). As part of this linguistic heritage, some look to the same medieval period as mentioned before. In the early medieval period, Galician was a language of poetry with a strong literary tradition. That tradition largely died out with the expansion of Castilian and the separation of Galician and Portuguese. Galician literature, including official public usage, has increased recently in response to post-industrial claims of regional identity.

Related to linguistic claims, the Galicians (and to a lesser extent, the Asturians) claim a strong Celtic heritage. Though the Celts once inhabited virtually all of Iberia, they lasted longest in the isolated northwest. Though the Galicians speak a Romance language, they nonetheless retained many traditional symbols associated with the Celts, including Celtic architecture and art, dress, and especially Celtic music (albeit with non-Celtic words).

In the late medieval and early modern periods, language, art, and music did play a part, but there were also particularly Galician developments which also helped set them apart. In Galicia, the process of dividing ones inheritance amongst all the sons led to increasingly fragmented parcels of land and particularly predatory nobles. Peasant-Noble conflict existed everywhere, but in Galicia it even reached the point where the peasants would build walls around their towns to keep the nobles out (acts which the nobles took as invitations to attack, and so in many cases such walls had the opposite effect). This came to a head in the revolt of the Irmandiños (“Members of the brotherhoods”) in the late 15th century. Galician peasants banded together to form irmandades (brotherhoods) which launched full offensives against abusive nobles (which included the majority of the nobles). Ultimately the revolt failed due to lack of cohesive leadership, inferior training, and inferior weapons.[30] This was a peculiarly Galician revolt and embodied many aspects which constituted ‘Galician-ness’ for a long time, but it should not be given too much credit. It was a regional revolt only in that it affected most of that specific region and was due to reasons specific to that region, but it had almost nothing to do with an identity as separate region. Rather, local nobles were not living up to expectations of what nobles should do, and the Galicians were fine being part of a larger Castilian monarchy just as long as their personal grievances against their lords were addressed. Nonetheless, the irmandiños did evolve into a system of regional resistance to oppression and Galicia did eventually (four centuries later), begin to assert itself as a unique region within a larger Spain.

Asturias

The Kingdom of Asturias has the honor of being the first Christian kingdom established after the Muslim invasion, though it was so weakly held together it can hardly be called a viable kingdom.[31] It rose to prominence across the north and northwest before being overshadowed by the Kingdom of León, the Kingdom of Pamplona, and the other kingdoms whose borders constantly shifted back and forth across the north. It had (and still has) its own language, Asturian, which is often associated with the more prominent Leonese. Asturias has never had quite the same regionalist tendencies as the previously discussed regions, however there was a brief consideration of separatism during the mid-17th century, following the example of many other regions. Even during that time and until recently, any form of regional independence was more prompted by economic factors than any form of ideological regionalism.[32] At the same time, most declarations of Asturian identity do focus on its independence as a region with its own historical borders. As much as it asserts its own cultural identity, it faces the challenges of possessing a non-Galician Celtic culture, a non-Leonese Astur-Leónese language, a long non-independent separate region, and a very inactive regional separatism. That mix of challenges, however, leaves a result which is somehow distinctly Asturian.

León

In modern times, León is incorporated into the larger autonomous community of Castile and León, though that larger grouping is not even 200 years old (since 1833). It too has its own language and its own history as an independent kingdom which participated in the Reconquista (primarily in Extremadura). Nonetheless, its gains in that war were soon eclipsed by Castilian settlement after the union of the Castilian and Leonese crowns. The Leonese, as a specific group, were therefore relegated to roughly where they began: the mountains just northeast of Portugal. They are currently one of the regions which are vaguely considering separatism, though that movement is not strong and historical León, though there were some riots after the initial union of the crowns, was generally not as restless as other territories of Spain.

Cantabria

Cantabria is a little different from the other kingdoms. It is the heartland of early Castile, and it technically speaks Castilian. For the most part, Cantabria’s identity seems to be centered on a unique, more ancient Castilian culture, highly distinct from what is in the rest of Castile. While they do not have their own language, as do the other regions, they do have a very distinct dialect which is almost different enough from standard Castilian to be considered its own language. They use the specific Cantabrian dialect in much the same way the other regions treat their own specific languages. While Castilians rightly include this region as part of Castile because of Castile’s early domains, Cantabria nonetheless identifies itself as somewhat distinct through its separate traditions, local legends, specific language, and even its climate (which is similar to other northern regions, but different from the rest of Castilian Spain). In contrast to the other Castilians, the Cantabrians use their early history as part of an independent Castile to distinguish themselves as the oldest Castilians. Nonetheless, that original identity as castilians was did not provide an overwhelming impetus to separate for most of Castile's history, and the primary division between Cantabria and the rest of Castile was more geographic isolation than political or ideological.[33] Their identity is therefore currently primarily as the Castilians who have most retained their original traditions, some of which are even pre-Roman (one could say they belong to the historical region or former kingdom of Castile, but not the cultural region of Castile).

Andalusia

Andalusia is actually a diverse collection of different southern regions. Some regions are dominated by their past as the economic portal of Spain to the rest of the world, while other regions were still largely inhabited by Muslims or Moriscos. These regions within Andalucia are largely linked through similar economies, foods, customs, and lesser formality than the rest of Castile. Theoretically, they speak Castilian and are the remnants of the Castilian Reconquista, and theoretically the Moors/Moriscos and their influence were removed with the respective expulsion edicts. In reality, several aspects of Moorish culture remained for a good part of the early modern period (as it did in most parts of Spain), whether in art, architecture (e.g. having interior-facing homes), social practices (including keeping women fairly hidden away in the home), and types of dress and dances.[34] Despite being made up of so many different regions, Andalusia has had a relatively shared identity for a while. It too had a conspiracy for revolt in the mid-17th century, when Catalonia and Portugal revolted and similar conspiracies existed elsewhere, such as Aragon.[35] It was not as confrontational as Catalonia at any point, though. Even so, the sum of the differences listed above led the region to petition for the same sort of independence as Catalonia and the Basque Countries following the collapse of the Franco Regime. The latter two were the first to be suggested for autonomy as historical nations, along with Galicia. Andalusia’s petition for autonomy on the same grounds was perceived as presumptuous because it had always been part of Castile after the Reconquista. Nonetheless, it was granted autonomy, and once it received autonomy, the system of regional autonomy was extended to all parts of the country which wanted it (Navarre declined).[36] A proper look at identity in Andalusia would include the different regions (Seville, Cádiz, Cordoba, Málaga, Granada, Almería, Jaén, and Huelva) but those will be ignored for the moment until someone chooses to add them.

Castile

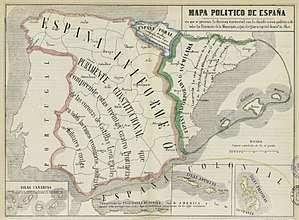

Castile as a whole enjoyed the status as the dominant group within Spain. Even before specific Castilianization efforts by the Bourbons and Franco, Castilian was the language of the bureaucracy, which discriminated against non-Castilian-speaking Spaniards. Further, the Spanish Empire was more of a Castilian empire, as the Americas were only officially open to Castilians (though that referred to inhabitants of Castile in contrast to the Crown of Aragon or Navarre, and so Galicians, etc., could still go), and most of the trade was channeled through Seville and later Cadiz (both of which are actually in Andalusia, but were part of the Kingdom of Castile. Castile had its own particular disadvantages as well, though. Regions like Catalonia refused to support Spain’s military efforts or its finances, as it perceived such efforts as a foreign enterprise. Therefore, Castilians bore the brunt of the taxes until the Bourbons.[37] It can sometimes be unclear whether “Castilian” always refers to just Castile or to the whole Kingdom of Castile in Spain when referring to such things as Castilian taxes or how only Castilians could go to the Americas. The map to the right shows the basic divisions of Spanish law and indicates that this did include those other regions, yet the fact that they can be referred to under a broad “Castile” shows that groups dominance over the others. The map at the top which shows the progress of the Reconquista linguistically also shows how Castilian continued expanding into new territory, especially after 1500. Because of this dominance, Castile did not have to fight for an identity in contrast to a competing identity. Instead, Castilian identity (and also Andalusian identity) is largely a collection of competing municipal identities (e.g. Madrid, Toledo, Burgos, Valladolid, etc.). At the same time, Castillian-ness became increasingly associated with Spanish-ness to the exclusion of other areas.

Other

These other regions share nothing in common except that their primary regional identity is either apathetic or conflicted.

La Rioja

La Rioja is situated on the border of Castile and the Basque Country, along the River Ebro. It is predominantly Castilian, but has a Basque minority. It never really had a significant regionalist movement and is primarily its own autonomous community now because the Basques wanted to join the Basque Country and the some Castilians wanted to join Old Castile. They were unable to really agree, and even Castilians were hesitant to join Old Castile for economic (agricultural) reasons. Therefore, they voted to remain independent.[38]

Extremadura

Extremadura was similarly unable to successfully decide. A small part of Extremadura speaks either Extremaduran or Fala, but they are largely inconsequential. Andalusia rejected attempts to join them on the grounds that Extremadura was too poor, and Extremadura itself felt that its other option, New Castile, was also too poor. Because of rejection by themselves or others and general isolation, they became an autonomous community.[39] It should be noted that many of the conquistadors came from this area, however that was mainly due to economic advancement in the New World. Spanish America therefore gained a slightly Extremaduran accent at first, though the impact on Extremadura itself was negligible in terms of identity or otherwise.

Murcia

Murcia was also fairly divided. Since the conclusion of the Reconquista, it was primarily Christian, and saw itself as primarily Castilian. Its independence is mainly for fiscal reasons instead of regional identity, and the significant Castilian element was still not strong enough to override finances.[40]

See also

References

- ↑ Ruiz, Teófilo F. (2001). Spanish society, 1400-1600 (1. publ. ed.). Harlow: Longman. p. 11. ISBN 0-582-28692-1.

- ↑ Rodríguez, Mateo Ballester (2010). La identidad española en la Edad Moderna (1556-1665) : discursos, símbolos y mitos. Madrid: Tecnos. p. 40. ISBN 978-84-309-5084-3.

- ↑ Wulff, Fernando (2003). Las esencias patrias : historiografía e historia antigua en la construccion de la identidad española (siglos XVI-XX). Barcelona: Crítica. pp. 29–41. ISBN 978-84-8432-418-8.

- ↑ Rodríguez, Mateo Ballester (2010). La identidad española en la Edad Moderna (1556-1665) : discursos, símbolos y mitos. Madrid: Tecnos. pp. 84–91. ISBN 978-84-309-5084-3.

- ↑ Fletcher, Richard (2006). Moorish Spain (2. paperback print. ed.). Berkeley, Calif. [u.a.]: Univ. of California Press. ISBN 0-520-24840-6.

- ↑ Ruiz, Teofilo F. (2001). Spanish society, 1400-1600 (1. publ. ed.). Harlow: Longman. pp. 101–103. ISBN 0-582-28692-1.

- ↑ Ruiz, Teofilo F. (2001). Spanish society, 1400-1600 (1. publ. ed.). Harlow: Longman. pp. 22–25. ISBN 0-582-28692-1.

- ↑ Alonso, Manuel Moreno (2010). El nacimiento de una nación (1a. ed.). Madrid: Cátedra. pp. 33–36. ISBN 978-84-376-2652-9.

- ↑ Elliott, J.H. (2002). Imperial Spain 1469-1716 (Repr. ed.). London [u.a.]: Penguin Books. pp. 274; 346–348. ISBN 0-14-100703-6.

- ↑ Muñoz, coord., José Ángel Sesma (2010). La Corona de Aragón en el centro de su historia, 1208-1458. Huesca: Instituto de Estudios Altoaragoneses. p. 22. ISBN 978-84-92522-16-3.

- ↑ Muñoz, coord., José Ángel Sesma (2010). La Corona de Aragón en el centro de su historia, 1208-1458. Huesca: Instituto de Estudios Altoaragoneses. p. 24. ISBN 978-84-92522-16-3.

- ↑ Wulff, Fernando (2003). Las esencias patrias : historiografía e historia antigua en la construccion de la identidad española (siglos XVI-XX). Barcelona: Crítica. p. 168. ISBN 978-84-8432-418-8.

- ↑ Fletcher, Richard (2006). Moorish Spain (2. paperback print. ed.). Berkeley, Calif. [u.a.]: Univ. of California Press. pp. 30, 57. ISBN 0-520-24840-6.

- ↑ Cowans, ed. by Jon (2003). Early modern Spain : a documentary history. Philadelphia, Pa.: Univ. of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 158–160. ISBN 978-0-8122-1845-9.

- ↑ Cowans, ed. by Jon (2003). Early modern Spain : a documentary history. Philadelphia, Pa.: Univ. of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 203–206. ISBN 978-0-8122-1845-9.

- ↑ Wulff, Fernando (2003). Las esencias patrias : historiografía e historia antigua en la construccion de la identidad española (siglos XVI-XX). Barcelona: Crítica. p. 167. ISBN 978-84-8432-418-8.

- ↑ Sahlins, Peter (1989). Boundaries : the making of France and Spain in the Pyrenees. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 287. ISBN 0-520-06538-7.

- ↑ Ruiz, Teofilo F. (2001). Spanish society, 1400-1600 (1. publ. ed.). Harlow: Longman. pp. 104–107. ISBN 978-0-582-28692-4.

- ↑ Ruiz, Teofilo F. (2001). Spanish society, 1400-1600 (1. publ. ed.). Harlow: Longman. pp. 195–197. ISBN 0-582-28692-1.

- ↑ Ruiz, Teofilo F. (2001). Spanish society, 1400-1600 (1. publ. ed.). Harlow: Longman. p. 15. ISBN 0-582-28692-1.

- ↑ Kern, Robert W. (1995). The regions of Spain : a reference guide to history and culture. Westport, Conn. [u.a.]: Greenwood Press. p. 89. ISBN 0-313-29224-8.

- ↑ Muñoz, coord., José Ángel Sesma (2010). La Corona de Aragón en el centro de su historia, 1208-1458. Huesca: Instituto de Estudios Altoaragoneses. p. 235. ISBN 978-84-92522-16-3.

- ↑ Ruiz, Teofilo F. (2001). Spanish society, 1400-1600 (1. publ. ed.). Harlow: Longman. p. 146. ISBN 0-582-28692-1.

- ↑ Elliott, J.H. (2002). Imperial Spain 1469-1716 (Repr. ed.). London [u.a.]: Penguin Books. pp. 280–283. ISBN 0-14-100703-6.

- ↑ Ruiz, Teofilo F. (2001). Spanish society, 1400-1600 (1. publ. ed.). Harlow: Longman. pp. 178–179. ISBN 0-582-28692-1.

- ↑ Ruiz, Teofilo F. (2001). Spanish society, 1400-1600 (1. publ. ed.). Harlow: Longman. p. 16. ISBN 0-582-28692-1.

- ↑ Wulff, Fernando (2003). Las esencias patrias : historiografía e historia antigua en la construccion de la identidad española (siglos XVI-XX). Barcelona: Crítica. pp. 156–167. ISBN 978-84-8432-418-8.

- ↑ Fletcher, Richard (2006). Moorish Spain (2. paperback print. ed.). Berkeley, Calif. [u.a.]: Univ. of California Press. pp. 57–58. ISBN 0-520-24840-6.

- ↑ Kern, Robert W. (1995). The regions of Spain : a reference guide to history and culture. Westport, Conn. [u.a.]: Greenwood Press. p. 237. ISBN 0-313-29224-8.

- ↑ Ruiz, Teofilo F. (2001). Spanish society, 1400-1600 (1. publ. ed.). Harlow: Longman. pp. 192–194. ISBN 0-582-28692-1.

- ↑ Fletcher, Richard (2006). Moorish Spain (2. paperback print. ed.). Berkeley, Calif. [u.a.]: Univ. of California Press. p. 26. ISBN 0-520-24840-6.

- ↑ Kern, Robert W. (1995). The regions of Spain : a reference guide to history and culture. Westport, Conn. [u.a.]: Greenwood Press. pp. 82–84. ISBN 0-313-29224-8.

- ↑ Kern, Robert W. (1995). The regions of Spain : a reference guide to history and culture. Westport, Conn. [u.a.]: Greenwood Press. p. 135. ISBN 0-313-29224-8.

- ↑ Ruiz, Teofilo F. (2001). Spanish society, 1400-1600 (1. publ. ed.). Harlow: Longman. p. 227. ISBN 0-582-28692-1.

- ↑ Elliott, J.H. (2002). Imperial Spain 1469-1716 (Repr. ed.). London [u.a.]: Penguin Books. p. 348. ISBN 0-14-100703-6.

- ↑ Kern, Robert W. (1995). The regions of Spain : a reference guide to history and culture. Westport, Conn. [u.a.]: Greenwood Press. pp. 9–11. ISBN 0-313-29224-8.

- ↑ Elliott, J.H. (2002). Imperial Spain 1469-1716 (Repr. ed.). London [u.a.]: Penguin Books. pp. 328–329. ISBN 0-14-100703-6.

- ↑ Kern, Robert W. (1995). The regions of Spain : a reference guide to history and culture. Westport, Conn. [u.a.]: Greenwood Press. p. 325. ISBN 0-313-29224-8.

- ↑ Kern, Robert W. (1995). The regions of Spain : a reference guide to history and culture. Westport, Conn. [u.a.]: Greenwood Press. pp. 175–176. ISBN 0-313-29224-8.

- ↑ Kern, Robert W. (1995). The regions of Spain : a reference guide to history and culture. Westport, Conn. [u.a.]: Greenwood Press. p. 229. ISBN 0-313-29224-8.