History of the Jews in Cincinnati

The history of the Jews in Cincinnati occupies a prominent place in the development of Jewish secular and religious life in the United States. Cincinnati is not only the oldest Jewish community west of the Allegheny Mountains but has also been an institutional center of American Reform Judaism for more than a century. The American Israelite, the longest-running Jewish weekly still published in the country, opened for business in the city in 1854.

19th century

Arrival of British Jews

The first identifiable Jew who settled in Cincinnati was Joseph Jonas, an English emigrant who arrived in the city via Philadelphia in 1817.[1] Jonas, a young man, decided to leave his home in Exeter, England, with the avowed intention of settling in Cincinnati. Friends in Philadelphia originally endeavored to dissuade him from going to a place so isolated from all association with his coreligionists. However, Jonas reassured them that he would succeed. For the first two years, he was the only Jew in the Midwestern town.

In 1819, Jonas was joined by three others, Lewis Cohen of London, Barnet Levi of Liverpool, and Jonas Levy of Exeter. On the High Holidays in the autumn of 1819, these four men, together with David Israel Johnson of Brookville, Indiana, (a frontier trading-station) conducted the first Jewish service west of the Appalachians. Similar services were held the next three years. Newcomers continued to arrive, the early settlers being mostly Jews from England.

The first Jewish child born in Cincinnati, Frederick A. Johnson (June 2, 1821), was the son of the above-mentioned David Israel Johnson and his wife, Eliza. This couple, also English, had removed to Cincinnati from Brookville, where they had first settled. The first couple to be married were Morris Symonds and Rebekah Hyams, whose wedding was celebrated on September 15, 1824. The first death in the community was that of Benjamin Leib (or Lape) in 1821. This man, who had not been known as a Jew, when he felt death to be approaching, asked that three of the Jewish residents of the town be called. He disclosed to them that he was a Jew. He had taken a Gentile spouse but who was Noachide, and had reared his children as Noachides, but he begged to be buried as a Jew. There was no Jewish burial-ground in the town. The few Jews living in the city at once proceeded to acquire a small plot of ground to be used as a cemetery and buried him there. It is known as the Old Jewish Cemetery, Cincinnati, this plot, which was afterward enlarged, was used as the cemetery of the Jewish community till the year 1849, after the Cholera epidemic.[2] At present this cemetery (oldest west of the Alleghenies) is situated in the heart of the city, on Chestnut Street near Central Avenue, in the Old West End.

There were not enough settlers to form a congregation until the year 1824, when the number of Jewish inhabitants of the town had reached about twenty. On January 4 that year a preliminary meeting was held to consider the advisability of organizing a congregation. Two weeks later, on January 18, the Congregation B'ne Israel was formally organized; those in attendance were Solomon Buckingham, David I. Johnson, Joseph Jonas, Samuel Jonas, Jonas Levy, Morris Moses, Phineas Moses, Simeon Moses, Solomon Moses, and Morris Symonds. On January 8, 1830, the Ohio General Assembly granted the congregation a charter whereby it was incorporated under the laws of the state.

For twelve years, the congregation worshiped in a room rented for the purpose; but, during all this time, the small congregation was exerting itself to secure a permanent home. Appeals were made to the Jewish congregations in various parts of the country. Philadelphia, Charleston, and New Orleans lent their assistance. Contributions were even received from Portsmouth, England, whence a number of Cincinnatians had emigrated, and from Barbados in the West Indies. On June 11, 1835, the cornerstone of the first synagogue was laid; and on September 9, 1836, the synagogue was dedicated with appropriate ceremonies. The members of the congregation had conducted the services up to this time. The first official reader was Joseph Samuels. He served a very short time, and was succeeded by Henry Harris, who was followed in 1838 by Hart Judah.

Early religious institutions

The first benevolent association was organized in 1838 with Phineas Moses as president: its object was to assist needy coreligionists. The first religious school was established in 1842, Mrs. Louisa Symonds becoming its first superintendent. This school was short-lived. In 1845, a Talmud Torah school was established, which gave way the following year to the Hebrew Institute, established by James K. Gutheim. This also flourished but a short time; when Gutheim departed for New Orleans, the career of the institute closed.

Center for German Jews

During the 1830s, quite a number of German Jews arrived in the city. On September 19, 1841, the B'ne Yeshurun congregation was organized by the Germans, and was incorporated under the laws of the state February 28, 1842. The first reader was Simon Bamberger. In 1847, James K. Gutheim was elected lecturer and reader of the congregation. He served till 1848, and was succeeded by H. A. Henry and A. Rosenfeld. In April 1854, Isaac Mayer Wise became the first rabbi of the B'ne Yeshurun congregation. In that same year, Wise’s brother-in-law, Edward Bloch, followed Wise to Cincinnati, and eventually founded a printing company that evolved into Bloch Publishing Company, the oldest Jewish publishing company in the U.S., which remained in Cincinnati until it moved to New York City in 1901.[3]

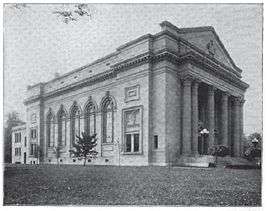

In 1866, the congregation built the architecturally notable Plum Street Temple, now known as the Isaac M. Wise Temple. The B'ne Israel congregation hired Max Lilienthal in June 1855. These leadership appointments gave the Jewish community of Cincinnati a commanding position. Owing to their efforts, Cincinnati became a center of Jewish life in America and the seat of a number of organizations that were national in scope. The institutions of Reform Judaism, namely, the Union of American Hebrew Congregations (UAHC, 1873), the Hebrew Union College (HUC, 1875), the Hebrew Sabbath-School Union (1886), and the Central Conference of American Rabbis (CCAR, 1889) were all founded in Cincinnati. In 1951, the UAHC (now called the Union for Reform Judaism) moved its headquarters to the demographic center of American Jewry in New York City [4]

Dr. Lilienthal died in office April 5, 1882. He was succeeded as rabbi of the Congregation B'ne Israel by Raphael Benjamin, who served till November 1888, when David Philipson, took charge of the congregation. Dr. Wise served as rabbi of the B'ne Yeshurun congregation till the day of his death, March 26, 1900; being succeeded by his associate, Dr. Louis Grossman. Dr. Grossman had been preceded as associate rabbi by Rabbi Charles S. Levi, who served from September 1889 to September 1898.

Educational work

The other congregations of the city, which continued to adhere to Orthodoxy, were the Adath Israel, organized in 1847; the Ahabath Achim, organized in 1848; and the Sherith Israel, organized in 1855. There were also a number of smaller congregations. Each of these congregations conducted its own religious school, and there were also two free religious schools; one holding its sessions in the schoolrooms of the Mound Street Temple (B'ne Israel), and the other, conducted under the auspices of the local branch of the Council of Jewish Women, meeting at the Jewish Settlement. One of these congregations enjoys the distinction of having petitioned overseas halakhic authority Rabbi Naftali Zvi Yehuda Berlin regarding the appropriate manner in which to inaugurate a Torah scroll in the synagogue. [R. Berlin's response is published in his She'elot Uteshuvot Meshiv Davar, I, no. 16, and possesses practical halakhic ramifications until today, as explained by Rabbi J. David Bleich in the latter's Contemporary Halakhic Problems V, p. 386.] A large Talmud Torah school was conducted by the Talmud Torah Association on Barr Street. Night classes for various English and industrial branches of study were a feature of the work of the Jewish Settlement. The Jewish Kitchen Garden Association conducted a large school for girls in the building of the United Jewish Charities every Sunday morning, where instruction is given in dressmaking, millinery, housekeeping, cooking, stenography, typewriting, and allied subjects. An industrial school for girls was conducted during the summer months in the vestry-rooms of the Plum street temple (B'ne Yeshurun), and one for boys during the school year in the Ohio Mechanics Institute building. There was a training-school for nurses in connection with the Jewish Hospital.

The Jewish charities of Cincinnati were exceptionally well organized. All the relief and educational agencies joined their forces in April 1896, and formed the United Jewish Charities. This body comprised the following federated societies: Hebrew General Relief Association, Jewish Ladies’ Sewing Society, Jewish Foster Home, Jewish Kitchen Garden Association, Boys’ Industrial School, Girls’ Industrial School, and Society for the Relief of Jewish Sick Poor. The United Charities also granted an annual subvention to the Denver Hospital for Consumptives and to the local Jewish Settlement Association. The seat of the National Jewish Charities is also in Cincinnati, where the national organization was called into being in May 1899. Besides the United Jewish Charities, Cincinnati supported the Jewish Hospital and the Home for the Jewish Aged and Infirm, and was one of the largest contributors to the Jewish Orphan Asylum at Cleveland.

The Jews of Cincinnati participated actively in civic life and filled many local positions of trust, as well as state, judicial, and governmental offices. Henry Mack, Charles Fleischmann, James Brown, and Alfred M. Cohen were elected members of the State Senate, and Joseph Jonas, Jacob Wolf, Daniel Wolf, and Harry M. Hoffheimer served in the State House of Representatives. Jacob Shroder was judge of the court of common pleas for a number of years, and Frederick S. Spiegel held the same position as of 1902. Julius Fleischmann was the mayor of the city. Nathaniel Newburgh was appointed appraiser of merchandise by President Cleveland during his first administration, and Bernhard Bettmann was collector of internal revenue since 1897. Lewis S. Rosenstiel, a grandson of Frederick A. Johnson—the first Jew born in the city, was the founder and chairman of Schenley Industries and was the nation’s largest distiller for half of the twentieth-century.

In 1900, the estimated Jewish population of the city stood around 15,000, in a total population of 325,902.

By 2008, the estimated Jewish population of the Cincinnati metropolitan area stood around 27,000.[5]

Newspapers

The first Jewish newspaper published in Cincinnati was the English-language The Israelite, established 1854. It was founded by Rabbi Wise and (after its initial issues, which were published by Charles F. Schmidt), it began to be published by Edward Bloch with the issue of July 27, 1855. Rabbi Wise also founded (and Bloch published) the German-language Die Deborah in 1855. The Israelite was renamed The American Israelite in 1874. Rabbi Wise’s son Leo Wise took over as its publisher from 1883–1884, and then he did so again, permanently, in 1888. The American Israelite still exists and is said to be the longest-running Jewish newspaper in the United States.[3] Another newspaper, The Sabbath Visitor, established 1874, was discontinued in 1892.

Businesses

The B. Manischewitz Company, LLC was founded by Rabbi Dov Behr Manischewitz, in Cincinnati in 1888. Their original product, the square matzah revolutionized matzoh making, previously the process used was to hand roll the matzoh and trim the edges.

In the late 1800s Jewish Russian immigrant Izzy Kadetz settled in Cincinnati, and offered his flair for cooking at the renowned St. Nicolas Hotel. A Cincinnati culinary institution, Izzy's Deli opened in 1901 as the first kosher style delicatessen West of the Alleghenies.

.

20th century

Notable Cincinnati Jews

- Theda Bara - American silent film and stage actress

- Steven Spielberg - Academy Award-winning film director

- Sarah Jessica Parker - Emmy award-winning American actress

- Jerry Rubin - American social activist, anti-war leader, and counterculture icon

- Jerry Springer - 56th Mayor of Cincinnati (1977–78)

- Albert Sabin - Medical researcher who developed oral polio vaccine

- Joseph Strauss - Chief structural engineer of the Golden Gate Bridge

- Isaac Mayer Wise - Rabbi, editor, author, and founder of Reform Judaism

- Kevin Youkilis - 3x All-Star, 2x World Series Champion baseball player

Notes

- ↑ Shevitz, Amy (2007). Jewish Communities on the Ohio River: A History. University Press of Kentucky. p. 25.

- ↑ International Jewish Cemetery Project Retrieved July 17, 2012.

- 1 2 Robert Singerman, “Bloch & Company: Pioneer Jewish Publishing House in the West”, Jewish Book Annual, Vol. 52, pp.110-130 (1994-95).

- ↑ URJ - History.

- ↑ "Survey: Cincinnati Jewish population stable". Cincinnati Business Courier. Sep 11, 2008. Retrieved 12 July 2014.

References

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Singer, Isidore; et al., eds. (1901–1906). "article name needed". Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Singer, Isidore; et al., eds. (1901–1906). "article name needed". Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls Company.- Jewish Encyclopedia

- By : Cyrus Adler & David Philipson

External links

- Hidden Jewish Cincinnati

- Jewish Federation of Cincinnati

- David's Voice - The Voice of Cincinnati's Jewish Community