History of the Hudson River

The Hudson River is a 315-mile (507 km) river in New York. The river is named after Henry Hudson, an Englishman sailing for the Dutch East India Company, who explored it in 1609, and after whom Canada's Hudson Bay is also named. It had previously been observed by Italian explorer Giovanni da Verrazano sailing for King Francis I of France in 1524, as he became the first European known to have entered the Upper New York Bay, but he considered the river to be an estuary. The Dutch called the river the North River – with the Delaware River called the South River – and it formed the spine of the Dutch colony of New Netherland. Settlements of the colony clustered around the Hudson, and its strategic importance as the gateway to the American interior led to years of competition between the English and the Dutch over control of the river and colony.

During the eighteenth century, the river valley and its inhabitants were the subject and inspiration of Washington Irving, the first internationally acclaimed American author. In the nineteenth century, the area inspired the Hudson River School of landscape painting, an American pastoral style, as well as the concepts of environmentalism and wilderness. The Hudson was also the eastern outlet for the Erie Canal, which, when completed in 1825, became an important transportation artery for the early-19th-century United States.

Names

The river was called Ca-ho-ha-ta-te-a ("the river")[1] by the Iroquois, and it was known as Muh-he-kun-ne-tuk ("river that flows two ways") by the Mohican tribe who formerly inhabited both banks of the lower portion of the river. The Delaware Tribe of Indians (Bartlesville, Oklahoma) considers the closely related Mohicans to be a part of the Lenape people,[2] and so the Lenape also claim the Hudson as part of their ancestral territory, naming the river Muhheakantuck ("river that flows two ways").[3]

The first known European name for the river was the Rio San Antonio as named by the Portuguese explorer in Spain's employ, Esteban Gomez, who explored the Mid-Atlantic coast in 1525.[4] Another early name for the Hudson used by the Dutch was Rio de Montaigne.[5] Later, they generally termed it the Noortrivier, or "North River", the Delaware River being known as the Zuidrivier, or "South River". Other occasional names for the Hudson included: Manhattes rieviere "Manhattan River", Groote Rivier "Great River", and de grootte Mouritse reviere, or "the Great Mouritse River" (Mouritse is a Dutch surname).[6] The translated name North River was used in the New York metropolitan area up until the early 1900s, with limited use continuing into the present-day.[7] The term persists in radio communication among commercial shipping traffic, especially below the Tappan Zee.[8] The term also continues to be used in names of facilities in the river's southern portion, such as the North River piers, North River Tunnels, and the North River Wastewater Treatment Plant. It is believed that the first use of the name Hudson River in a map was in a 1740, in a map created by the cartographer John Carwitham.[9]

In 1939, the magazine Life described the river as "America's Rhine", comparing it to the 40-mile (64 km) stretch of the Rhine in Central and Western Europe.[10]

Pre-Columbian era

The area around Hudson River was inhabited by indigenous peoples ages before Europeans arrived. The Algonquins lived along the river, with the three subdivisions of that group being the Lenape (also known as the Delaware Indians), the Wappingers, and the Mahicans.[11] The lower Hudson River was inhabited by the Lenape Indians.[12] In fact, the Lenape Indians were the people that waited for the explorer Giovanni da Verrazzano onshore, traded with Henry Hudson, and sold the island of Manhattan.[12] Further north, the Wappingers lived from Manhattan Island up to Poughkeepsie. They lived a similar lifestyle to the Lenape, residing in various villages along the river. They traded with both the Lenape to the south and the Mahicans to the north.[11] The Mahicans lived in the northern valley from present-day Kingston to Lake Champlain,[12] with their capital located near present-day Albany.[11]

The Lenape, the Wappingers, and the Mahicans were speakers of languages that were part of Algonquin language family. As such, the three subdivisions were able to communicate with each other. Their relations with each other were mostly peaceful.[12][11] However, the Mahicans were often in direct conflict with the Mohawk Indians to the west, which were a part of the Iroquois nation. The Mohawks would sometimes raid Mahican villages from the west.[11]

The Algonquins in the region lived mainly in small clans and villages throughout the area. One major fortress was called Navish, which was located at Croton Point, overlooking the Hudson River. Other fortresses were located in various locations throughout the Hudson Highlands. Villagers lived in various types of houses, which the Algonquins called Wigwams. The houses could be circular or rectangular. Large families often lived in longhouses that could be a hundred feet long.[12] At the associated villages, the indigenous peoples grew corn, beans, and squash. They also scavenged for other types of plant foods, such as various types of nuts and berries. In addition to agriculture, they also fished for food in the river, focusing on various species of freshwater fish, as well as several variations of striped bass, sturgeon, herring, and shad. Oyster beds were also common on the river floor, which provided an extra source of nutrition. Land hunting consisted of turkey, deer, rabbits, and other animals.[12]

Exploration, colonization, and revolution: 1497 to 1800

Exploration of the Hudson River

In 1497, John Cabot traveled along the coast and claimed the entire country for England; he is credited with the Old World's discovery of continental North America.[4] In 1524, Florentine explorer Giovanni da Verrazzano visited the bay of New York, in service of Francis I of France.[4] On his voyage, Verrazano sailed north along the Atlantic seaboard, starting in the Carolinas. Verrazano sailed all the way to New York Harbor, which he thought was the mouth of a major river. Verrazano sailed his boat into the harbor, and possibly sailed over what is now Battery Park (Battery Park was created with landfill). However, Verrazano never sailed up the Hudson River, and left the harbor shortly thereafter.[13] A year later, Estevan Gomez, a Portuguese explorer sailing for Spain in search of the Northwest Passage visited New York Bay. The extent of his explorations in the bay is unknown. Yet as Charles H. Winfield has noted, as late as 1679, there was a tradition among the First Nations that the Spanish arrived before the Dutch, and that from them it was that the natives obtained the maize or Spanish wheat. Maps of that era based on Gomez's map labeled the coast from New Jersey to Rhode Island, as the "land of Estevan Gomez".[4]

In 1598 some Dutch employed by the Greenland Company wintered in the Bay.[4] Eleven years later, the Dutch East India Company financed English navigator Henry Hudson in his attempt to search for the Northwest Passage. During this attempt, Henry Hudson decided to sail his ship up the river that would later be named after him. As he continued up the river, its width expanded, into Haverstraw Bay, leading him to believe he had successfully reached the Northwest Passage. He docked his ship on the western shore of Haverstraw Bay and claimed the territory as the first Dutch settlement in North America. He also proceeded upstream as far as present-day Troy before concluding that no such strait existed there.[14]

Dutch colonization

After Henry Hudson realized that the Hudson River was not the Northwest Passage, the Dutch began examine the region for potential trading opportunities.[15] Dutch explorer and merchant Adriaen Block led a voyage up the lower Hudson River, the East River, and out into Long Island Sound. This voyage determined that the fur trade would be profitable in the region. As such, the Dutch established the colony of New Netherland.[16]

The Dutch settled three major outposts: New Amsterdam, Wiltwyck, and Fort Orange.[15] New Amsterdam was founded at the mouth of the Hudson River, and would later become known as New York City. Wiltwyck was founded roughly halfway up the Hudson River between New Amsterdam and Fort Orange. That outpost would later become Kingston. Fort Orange was the outpost that was the furthest up the Hudson River. That outpost would later become known as Albany.[15]

New Netherland and its associated outposts were set up as fur-trading outposts.[17] The Dutch attempted to form a trade alliance with the Mahicans, angering the Mohawk nation and provoking hostilities between the two tribes. The Natives began to trap furs at a quicker pace and then sold them to the Dutch for luxuries. This trade would eventually deplete the supply of those animals in their territory, decreasing the food supply in the process. The focus on furs also made the Natives economically dependent on the Dutch for trade.[11]

The Dutch West India Company operated a monopoly on the region for roughly twenty years before other businessmen were allowed to set up their own ventures in the colony.[15] New Amsterdam quickly became the colony's most important city, operating as its capital and its merchant hub.[17] The other outposts functioned as settlements in the wilderness. At first, the colony was made up of mostly single adventures looking to make money, but over time the region transitioned into maintaining family households. New economic activity in the form of food, tobacco, timber, and slaves was eventually incorporated into the colonial economy.[15]

In 1647, Director-General Peter Stuyvesant took over management of the colony. He found the colony in chaos due to a border war with the English along the Connecticut River, and Indian battles throughout the region. Stuyvesant quickly cracked down on smuggling and associated activity before expanding the outposts along the Hudson River, especially Wiltwyck at the mouth of Esopus Creek. Stuyvesant attempted to establish a fort midway up the Hudson River. However, before that could be done, the British invaded New Netherland via the port of New Amsterdam.[15] Given that the city of New Amsterdam was largely defenseless, Stuyvesant was forced to surrender the city and the colony to the British.[18] New Amsterdam and the overall colony of New Netherland was renamed New York, after the Duke of York.[18] The Dutch regained New York temporarily, only to relinquish it again a few years later, thus ending Dutch control over New York and the Hudson River.[18]

British colonization

Under British colonial rule, the Hudson Valley became an agricultural hub, with manors being developed on the east side of the river. At these manors, landlords rented out land to their tenants, letting them take a share of the crops grown while keeping and selling the rest of the crops.[19] Tenants were often kept at a subsistence level so that the landlord could minimize his costs. They also held immense political power in the colony due to driving such a large proportion of the agricultural output. Meanwhile, land west of Hudson River contained smaller landholdings with many small farmers living off the land. A large crop grown in the region was grain, which was largely shipped downriver to New York City, the colony's main seaport, for export back to Great Britain. In order to export the grain, colonial merchants were given monopolies to grind the grain into flour and export it.[19] Grain production was also at high levels in the Mohawk River Valley.[19]

The Albany Congress took place at Albany City Hall in 1754,[20] situated close to the Hudson River.[21] This meeting included officials from both the colonies and from the Iroquois. The subject of the meeting referred to tensions between the British and the French and the prelude to the French and Indian Wars. At the meeting, residents of the city of Albany were able to come into contact with people from the rest of the colonies, which was an interesting experience for many citizens of the city.[20] The result of the Congress was the Albany Plan of Union, which was the first attempt to create a unified government. The plan included 7 of the English colonies in North America.[22] The plan itself consisted of council with members selected by colonial governments.[22] The British government would select a president-general to oversee the new legislative body.[23] The new colonial body would deal with Colonial-Indian affairs as well as settle territorial disputes between colonies. Although this plan was never ratified by the colonial governments, the plan created a framework for later efforts to create a unified continental government during the American Revolution.[22] In addition, the colonial governments were able to sign a treaty with the Iroquois in advance of the upcoming war with the French.[24]

Revolutionary War

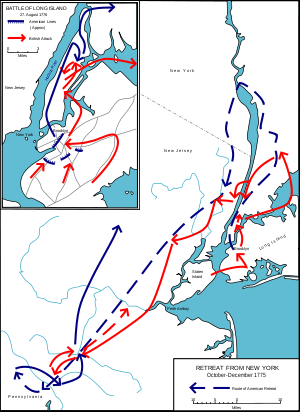

The Hudson River was a key river during the Revolution. The Hudson River was important for a few reasons. Firstly, the Hudson's connection to the Mohawk River allowed travelers to eventually get to the Great Lakes and the Mississippi River. In addition, the river's close proximity to Lake George and Lake Champlain would allow the British navy to control the water route from Montreal to New York City.[25] In doing so, the British, under general John Burgoyne's strategy, would be able to cut off the patriot hub of New England (which is on the eastern side of the Hudson River) and focus on rallying the support of loyalists in the South and Mid-Atlantic regions. The British knew that total occupation of the colonies would be unfeasible, which is why this strategy was chosen.[26]

As a result of the strategy, numerous battles were fought along the river and in nearby waterways. August 27, 1776, the Battle of Long Island was fought in Brooklyn on the eastern shore of the Narrows, the mouth of the Hudson River. Utilizing the vast natural harbor that is New York Harbor, the British sent in an entire armada in order to take on Washington's army in battle. The British, led by General William Howe first arrived in Staten Island, on the western shore of the Narrows. The armada then sailed across the Narrows to a waiting Continental Army. Washington's army was vastly outnumbered at the battle with 12,000 soldiers; the British had 45,000 soldiers. As expected, the British badly defeated the continentals at the battle and nearly crushed the rebellion.[27] However, under the cover of night, Washington ordered the camp fires to be extinguished, and then he and his army fled under the cover of darkness and fog across the East River by boat to Manhattan. The army then marched north to Harlem.[28] As a result of the battle, the British took control of New York City and the harbor, and thus they took control of the mouth of the Hudson River. The British would turn New York City into its headquarters for the war, and occupy it for the rest of the war. The harbor would later be used for prison ships to hold the captured American soldiers.[29]

On September 15, 1776, The Battle of Harlem Heights was fought in what is now Morningside Heights, Upper Manhattan. After Washington's army retreated to the northern section of the Manhattan Island, British troops pursued his army. Washington was just finishing a report about the Battle of Long Island when the British began to advance on his position. Washington then counterattacked the British with a plan of his own. Washington ordered a feint in order to fix the British army into a favorable position. Once this was accomplished, Washington ordered Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Knowlton, his rangers, and other units to flank around the right side of the British and attack from the rear. The plan almost worked, but some of the Continental troops attacked too early, allowing the British to retreat and await reinforcements. Once those reinforcements began to arrive, Washington called off the attack. Although not a complete defeat of the British attacking force, the battle was nonetheless a Continental Army victory, the first of the war. This fact greatly enhanced troop morale.[30] Washington would later retreat further north to White Plains, New York as the British pursued him and his army.[31]

While the British advanced towards Washington's Army, Washington decided to take a stand in White Plains. In October, 1776, Howe's army advanced from New Rochelle, and Scarsdale. Washington set up defensive positions in the hills around the village. When the British attacked, the British managed to break the Continental's defenses at Chatterton Hill, now known as Battle Hill. Once the British managed to reach the top of the hill, Washington was forced to retreat. The main positive for Washington after this battle was that he managed to avoid being enveloped by the British Army.[32] Washington ordered his men to retreat across the Hudson River, eventually reaching New Jersey and Pennsylvania.[33] Because Washington was able to preserve what was left of his army, this retreat would eventually lead to the successful surprise attacks on Trenton, New Jersey and Princeton, New Jersey in December of the same year.[32] Fort Washington in Upper Manhattan later fell after this retreat.[33]

Once Washington retreated to Pennsylvania, New England militias had to fortify the Hudson Highlands, a choke point on the river north of Haverstraw Bay. As a result, the Continentals started building Fort Clinton on the other side of the river from Fort Montgomery. In the year 1777, Washington expected General Howe to sail his army north to Saratoga in order to meet up with General Burgoyne. This would result in the Hudson River being sealed off. However, Howe surprised Washington by sailing his army south to Philadelphia, conquering the Patriot capital. Washington was out of position and sought to defend Philadelphia, but to no avail. Meanwhile, Howe left Sir Henry Clinton in charge of a smaller force to be docked in New York City, with the permission to strike the Hudson Valley at any time. On October 5, 1777, Clinton's army did so. At the Battle of the Hudson Highlands, Clinton's force sailed up the Hudson River and attacked the twin forts. Along the way, the army looted and pillaged the village of Peeksill. The Continentals fought hard at the battle, but they were badly outnumbered and were fighting in unfinished forts. Washington's men were caught between defending Philadelphia and defending the Hudson Valley. In the end, the British took the fort, as well as taking Philadelphia around the same time. However, Clinton and his men returned to New York City soon afterward.[34]

The Continentals later decided to build the Great West Point Chain in order to prevent another British fleet from sailing up the Hudson River in a similar manner as during the previous battle. The chain that was by the forts was simply circumvented by the British army via attacking on the shores. The new chain, designed by engineer Captain Thomas Machin, could have theoretically been lowered in order to let friendly ships sail down the river, but the chain was never tested, and was later discarded after the war.[35]

In 1777, a major battle, part of the Battles of Saratoga, was unfolding 30 miles north of Albany in Saratoga, New York.[34] British general Burgoyne sought to put into action his plan of taking over Albany and the Hudson River. Burgoyne and his army advanced southward from Canada towards Albany. Meanwhile, an army led by General Barry St. Leger marched east along the Mohawk River towards the same location,[36] taking Fort Ticonderoga along the way. This fort was (and is) located at the southern end of Lake Champlain, and thus was seen as critical in defending Albany.[37] Once Burgoyne took the fort, he made the mistake of deciding not to take the water route along Lake George, instead deciding to take the land route from the fort. Philip Schuyler punished Burgoyne for this mistake. He and his army chopped down trees and littered the pathway that Burgoyne would have to take through the swampy wilderness of the area. As a result of the decision to march south, Burgoyne's supply lines were strained.[37]

Burgoyne sent a column of his troops into Vermont in the hopes of securing needed supplies. However, Continental general John Stark and the New Hampshire-Vermont Militia thwarted Burgoyne's resupply run in the Battle of Bennington. The lack of supplies and the surrender of his column severely weakened his army. Meanwhile, Continental general Benedict Arnold halted the advance of General St. Ledger during the Siege of Fort Stanwix. This had the effect of preventing a British army from attacking the rear of the American troops during the Battle of Saratoga.[37] Burgoyne expected Sir Henry Clinton, under the orders of General Howe, to aid him in the invasion by sailing up the Hudson River from the south.[36] However, Howe's attack on Philadelphia diverted troops needed up in Saratoga. In addition, Washington prevented reinforcements from Howe's army from reaching Burgoyne. Meanwhile, Clinton's army was busy battling in the Hudson Highlands, as well as raiding villages in the Hudson Valley. As a result, Henry Clinton's fleet never reached Saratoga in time.[34]

Both the British and the American armies fought the Battles of Saratoga. Burgoyne still expected assistance from Henry Clinton, so his army dug in and waited. Clinton's forces did sail up the Hudson River, taking the Hudson Highlands forts as well as burning down Kingston (the NY State Capital at the time), but Clinton was forced to sail back to New York City in order to supply reinforcements after Howe's forces left to take Philadelphia.[38] As a result, Burgoyne never received the assistance he needed. Burgoyne's army was now at roughly 6800 men and was surviving on reduced rations.[38] On October 7, 1777, Burgoyne's army attempted to sweep around the American army in a last-ditch effort to escape from being surrounded,[38] but an American counterattack led by General Horatio Gates successfully surrounded the British Army.[36] An offensive by Benedict Arnold (which led to him being wounded in the leg) pushed Burgoyne closer to surrendering.[36] In the end, Burgoyne surrendered his army to the Americans on October 17. This battle would later be known as the turning point of the war. In addition, this battle convinced the French that the American Continentals could beat a European army. As a result, the French joined the war on the side of the Americans.[38]

During Benedict Arnold's control over West Point, he began weakening its defenses, including neglecting repairs on the West Point Chain.[39] At the time, Arnold was secretly loyal to the British, and planned to hand off West Point's plans to British major John André at Snedeker's Landing (or Waldberg Landing) on the wooded west shore of Haverstraw Bay.[40] On September 21, 1780, André sailed up the river on the HMS Vulture to meet Arnold. The next morning, an outpost at Verplanck's Point fired on the ship, which sailed back down river. André was forced to return to New York City by land;[41](pp151–6) however, he was captured near Tarrytown on September 23 by three Westchester militiamen, and later was hanged. Arnold later fled to New York City using the HMS Vulture.[41](p159)

Industrial Revolution

Canal era

.jpg)

At the beginning of the 19th century, transportation away from the US east coast was difficult. Boat travel was still the fastest mode of transportation at the time, as automobiles and rail transportation were still being developed. In order to facilitate boat travel throughout the interior of the United States, numerous canals were constructed between internal bodies of water in the country. These canals would transfer freight throughout the inland US.[42][43]

One of the most significant canals of this era was the Erie Canal. For about a hundred years, various groups had sought to have a canal built between the Great Lakes and the Hudson River. This would link the frontier region of the United States to the Port of New York, a significant seaport during that time period as it is today.[43] Construction of the canal began in 1817 and finished in 1825.[42] Originally called "Clinton's Ditch", after NY Governor DeWitt Clinton,[44] the canal proved to be a success, returning revenues of over $121 million after an initial construction cost of only $7 million.[43] After the canal was built, freight could travel from many frontier cities, such as Pittsburgh, Chicago, and Cleveland, to Lake Erie, then to Buffalo and the entrance to the canal, through the canal to the Hudson River, and then south to New York City.[43] The completion of the canal enhanced the development of the American West, allowing settlers to travel west, then send goods back to market in frontier cities, and then eventually export goods via the Hudson River and New York City. The completion of the canal made New York City one of the most vital ports in the nation, surpassing the Port of Philadelphia and ports in Massachusetts.[43][44][45]

The Erie Canal was not the only canal built that connects to the Hudson River.[45] After the completion of the Erie Canal, smaller canals were built to connect with the new system. The Champlain Canal was built to connect the Hudson River near Troy to the southern end of Lake Champlain. This canal allowed boaters to travel from the St. Lawrence Seaway, and then British cities such as Montreal to the Hudson River and New York City.[45] Another major canal was the Oswego Canal, which connected the Erie Canal to Oswego and Lake Ontario. This canal could be used to bypass Niagara Falls.[45] The Cayuga-Seneca Canal connected the Erie Canal to Cayuga Lake and Seneca Lake.[45] Farther south, the Delaware and Hudson Canal was built between the Delaware River at Honesdale, Pennsylvania, and the Hudson River at Kingston, New York. This canal enabled the transportation of coal, and later other goods as well, between the Delaware and Hudson River watersheds.[46] The combination of these canals made the Hudson River one of the most vital waterways for trade in the nation.[45]

In 1823, Troy's dam and lock were completed; its sloop lock was rebuilt in 1854.[47]

Hudson River School

Hudson River School paintings reflect three themes of America in the 19th century: discovery, exploration, and settlement.[48] The paintings also depict the American landscape as a pastoral setting, where human beings and nature coexist peacefully. Hudson River School landscapes are characterized by their realistic, detailed, and sometimes idealized portrayal of nature, often juxtaposing peaceful agriculture and the remaining wilderness, which was fast disappearing from the Hudson Valley just as it was coming to be appreciated for its qualities of ruggedness and sublimity.[49] In general, Hudson River School artists believed that nature in the form of the American landscape was an ineffable manifestation of God,[50] though the artists varied in the depth of their religious conviction. They took as their inspiration such European masters as Claude Lorrain, John Constable and J. M. W. Turner.[51] Their reverence for America's natural beauty was shared with contemporary American writers such as Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson.[52] The Düsseldorf school of painting had a direct influence on the Hudson River School.[53]

The school characterizes the artistic body, its New York location, its landscape subject matter, and often its subject, the Hudson River.[54] While the elements of the paintings were rendered realistically, many of the scenes were composed as a synthesis of multiple scenes or natural images observed by the artists. In gathering the visual data for their paintings, the artists would travel to extraordinary and extreme environments, which generally had conditions that would not permit extended painting at the site. During these expeditions, the artists recorded sketches and memories, returning to their studios to paint the finished works later.

The artist Thomas Cole is generally acknowledged as the founder of the Hudson River School.[55] Cole took a steamship up the Hudson in the autumn of 1825, the same year the Erie Canal opened, stopping first at West Point, then at Catskill landing. He hiked west high up into the eastern Catskill Mountains of New York State to paint the first landscapes of the area. The first review of his work appeared in the New York Evening Post on November 22, 1825.[56] At that time, only the English native Cole, born in a landscape where autumnal tints were of browns and yellows, found the brilliant autumn hues of the area to be inspirational.[55] Cole's close friend, Asher Durand, became a prominent figure in the school as well.[57] Painters Frederic Edwin Church and Albert Bierstadt were the most successful painters of the school.[54]

19th and 20th centuries

The first railroad in New York, the Mohawk and Hudson Railroad, opened in 1831 between Albany and Schenectady on the Mohawk River, enabling passengers to bypass the slowest part of the Erie Canal.[58]

The Hudson Valley proved attractive for railroads, once technology progressed to the point where it was feasible to construct the required bridges over tributaries. The Troy and Greenbush Railroad was chartered in 1845 and opened that same year, running a short distance on the east side between Troy and Greenbush, now known as East Greenbush (east of Albany). The Hudson River Railroad was chartered the next year as a continuation of the Troy and Greenbush south to New York City, and was completed in 1851. In 1866 the Hudson River Bridge opened over the river between Greenbush and Albany, enabling through traffic between the Hudson River Railroad and the New York Central Railroad west to Buffalo. When the Poughkeepsie Bridge opened in 1889, it became the longest single-span bridge in the world.

The New York, West Shore and Buffalo Railway began at Weehawken Terminal and ran up the west shore of the Hudson as a competitor to the merged New York Central and Hudson River Railroad. Construction was slow, and was finally completed in 1884; the New York Central purchased the line the next year.

The Upper Hudson River Valley was also useful for railroads. Sections of the Rensselaer and Saratoga Railroad, Troy and Boston Railroad and Albany Northern Railroad ran next to the Hudson between Troy and Mechanicville. North of Mechanicville the shore was bare until Glens Falls, where the short Glens Falls Railroad ran along the east shore. At Glens Falls the Hudson turns west to Corinth before continuing north; at Corinth the Adirondack Scenic Railroad begins to run along the Hudson's west bank. The original Adirondack Railway opened by 1871, ending at North Creek along the river. In World War II an extension opened to Tahawus, the site of valuable iron and titanium mines. The extension continued along the Hudson River into Hamilton County, and then continued north where the Hudson makes a turn to the west, crossing the Hudson and running along the west shore of the Boreas River. South of Tahawus the route returned to the east shore of the Hudson the rest of the way to its terminus.

During the Industrial Revolution, the Hudson River became a major location for production, especially around Albany and Troy. The river allowed for fast and easy transport of goods from the interior of the Northeast to the coast. Hundreds of factories were built around the Hudson, in towns including Poughkeepise, Newburgh, Kingston, and Hudson. The North Tarrytown Assembly (later owned by General Motors), on the river in Sleepy Hollow, was a large and notable example. The river links to the Erie Canal and Great Lakes, allowing manufacturing in the Midwest, including automobiles in Detroit, to use the river for transport.[59](pp71–2) With industrialization came new technologies for transport, including steamboats for faster transport. In 1807, the North River Steamboat (later known as Clermont), became the first commercially successful steamboat.[60] It carried passengers between New York City and Albany along the Hudson River.

On September 14, 1901, then-US Vice President Theodore Roosevelt was at Lake Tear of the Clouds after returning from a hike to the Mount Marcy summit when he received a message informing him that President William McKinley, who had been shot two weeks earlier but was expected to survive, had taken a turn for the worse. Roosevelt hiked down the mountain to the closest stage station at Long Lake, New York. He then took a 40 miles (64 km) midnight stage coach ride through the Adirondacks to the Adirondack Railway station at North Creek, where he discovered that McKinley had died. Roosevelt took the train to Buffalo, New York, where he was officially sworn in as President.[61] The 40-mile route is now designated the Roosevelt-Marcy Trail.[62]

In 1910, pilot Glenn Curtiss broke the American flight distance record. He flew his plane for five hours from a field near Albany to Governor's Island just south of Manhattan, flying over the Hudson River for most of his flight. The flight was 152 miles long, and he made one planned stop in Poughkeepsie, which was roughly the midpoint of the flight. He also made an unplanned stop just south of Spuyten Duyvil in Uptown Manhattan because he was low on fuel. A train full of reporters followed his plane the entire way, and the mayor of Albany gave Curtiss a letter to give to the mayor of New York City. Importantly, Curtiss' flight demonstrated that aircraft could eventually be used as a means for transportation between two major cities.[63]

In 1965, governor Nelson Rockefeller proposed the Hudson River Expressway, a limited-access highway from the Bronx to Beacon. An 8-mile section was built from Ossining to Peekskill, now part of U.S. Route 9; the rest of the highway was never built due to local opposition.[64]

Contemporary

.jpg)

In 2004, Christopher Swain became the first person to swim the entire length of the Hudson River. The swim took 36 days to complete, along the entire 315 miles of the Hudson from the Adirondacks to New York City. Swain took part in the swim in order to bring attention to the need to make the river safe for drinking and swimming. He braved a combination of rapids, dams, snapping turtles, and pollution in order to complete his journey. The marathon swim was a major part of Swim for the River, a documentary detailing the history of pollution in the Hudson River and the fight against it.[65]

On January 15, 2009, US Airways Flight 1549 made an emergency ditching onto the Hudson River beside Manhattan. The flight was a domestic commercial passenger flight with 150 passengers and 5 crew members traveling from LaGuardia Airport in New York City to Charlotte Douglas International Airport in Charlotte. After striking a flock of Canada geese during its initial climb out, the airplane lost engine power and ditched in the Hudson River off Midtown Manhattan with no loss of human life. All 155 occupants safely evacuated the airliner, and were quickly rescued by nearby ferries and other watercraft. The airplane was still virtually intact though partially submerged and slowly sinking. The entire crew of Flight 1549 was later awarded the Master's Medal of the Guild of Air Pilots and Air Navigators.[66] It was described by NTSB board member Kitty Higgins as "the most successful ditching in aviation history".[67]

On October 3, 2009 the Poughkeepsie-Highland Railroad Bridge reopened as the Walkway over the Hudson. It is a pedestrian walkway over the Hudson River that opened as part of the Hudson River Quadricentennial Celebrations, and it connects over 25 miles of existing pedestrian trails.

In 2016, a humpback whale was spotted swimming in the Hudson River west of 63rd Street in Manhattan. Whales have become a more common site in the river recently. This is because of a combination of cleanup of waste in the river as well as conservation of wildlife that creates a hospitable habitat for the whales. Whales have been spotted all the way up to the George Washington Bridge. The whales are especially prominent during feeding season in the fall. State and federal officials are warning kayakers and boaters to slow down and stay at least 100 feet from any whales in the area in order to not distress or hurt the whales.[68]

References

- ↑ https://archive.org/stream/aboriginalplacen00beau/aboriginalplacen00beau_djvu.txt

- ↑ http://www.delawaretribe.org/services-and-programs/historic-preservation/states-and-counties-covered-by-dthpo/

- ↑ Gennochio, Benjamin (September 3, 2009). "The River’s Meaning to Indians, Before and After Hudson". nytimes.com. The New York Times. Retrieved December 30, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 History of the County of Hudson, Charles H. Winfield, 1874, p. 1-2

- ↑ Ingersoll, Ernest (1893). Rand McNally & Co.'s Illustrated Guide to the Hudson River and Catskill Mountains. Chicago, Illinois: Rand, McNally & Company. p. 19. Retrieved January 6, 2015.

- ↑ Jacobs, Jaap (2005). New Netherland: A Dutch Colony in Seventeenth-Century America. Netherlands: Brill Publishers. p. 11. ISBN 9004129065. OCLC 191935005.

- ↑ Steinhauer, Jennifer (May 15, 1994). "Smell of the Forest". The New York Times. Retrieved December 30, 2014.

- ↑ Stanne, Stephen P.; Panetta, Roger G.; Forist, Brian E. (1996). The Hudson, An Illustrated Guide to the Living River. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 9780813522715. OCLC 32859161.

- ↑ Roberts, Sam (8 March 2017). "Some Credit for Henry Hudson, Found in a 280-Year-Old Map". The New York Times.

- ↑ "The Hudson River: Autumn Peace Broods over America's Rhine". Life. October 2, 1939. p. 57. Retrieved December 31, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Alfieri, J.; Berardis, A.; Smith, E.; Mackin, J.; Muller, W.; Lake, R.; Lehmkulh, P. (June 3, 1999). "The Lenapes: A study of Hudson Valley Indians" (PDF). Poughkeepsie, New York: Marist College. Retrieved May 25, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Levine, David (June 24, 2016). "Hudson Valley's Tribal History". Hudson Valley Magazine. Retrieved May 24, 2017.

- ↑ "Giovanni Verrazano". timesmachine.nytimes.com. New York Times. September 15, 1909. Retrieved March 28, 2016.

- ↑ Cleveland, Henry R. "Henry Hudson Explores the Hudson River". history-world.org. International World History Project. Retrieved February 3, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Dutch Colonies". nps.gov. National Park Service. Retrieved June 26, 2016.

- ↑ Varekamp, Johan Cornelis; Varekamp, Daphne Sasha (Spring–Summer 2006). "Adriaen Block, the discovery of Long Island Sound and the New Netherlands colony: what drove the course of history?" (PDF). Wrack Lines. Retrieved June 11, 2017.

- 1 2 Rink, Oliver A. (1986). Holland on the Hudson: An Economic and Social History of Dutch New York. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. pp. 17–23, 264–266. ISBN 978-0801495854. Retrieved June 26, 2016.

- 1 2 3 Roberts, Sam (August 25, 2014). "350 Years Ago, New Amsterdam Became New York. Don't Expect a Party.". New York Times. Retrieved June 26, 2016.

- 1 2 3 Leitner, Jonathan. "Transitions in the Colonial Hudson Valley: Capitalist, Bulk Goods, and Braudelian". Journal of World-Systems Research. 22 (1): 214–246. Retrieved January 4, 2017.

- 1 2 Bielinski, Stefan. "The Albany Congress". The Albany Congress. New York State Museum. Retrieved January 5, 2017.

- ↑ "City Hall". New York State Museum. New York State Museum. Retrieved January 5, 2017.

- 1 2 3 "Albany Plan of Union, 1754". MILESTONES: 1750–1775. Office of the Historian. Retrieved January 5, 2017.

- ↑ "Albany Plan of Union 1754". The Avalon Project. Yale Law School. Retrieved January 5, 2017.

- ↑ "Albany Congress". American History Central. R.Squared Communications LLC. Retrieved January 5, 2017.

- ↑ Mansinne, Jr., Major Andrew. "The West Point Chain and Hudson River Obstructions in the Revolutionary War" (PDF). desmondfishlibrary.org. Desmond Fish Library. Retrieved March 8, 2016.

- ↑ Carroll, John Martin; Baxter, Colin F. (August 2006). The American Military Tradition: From Colonial Times to the Present (2nd ed.). Lanham, Maryland: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, Inc. pp. 14–18. ISBN 9780742544284. Retrieved March 8, 2016.

- ↑ Hevesi, Dennis (August 27, 1993). "A Crucial Battle In the Revolution". New York Times. Retrieved March 8, 2016.

- ↑ "Governor's Island: The Battle of Brooklyn". www.nps.gov. National Park Service. Retrieved March 8, 2016.

- ↑ "The HMS Jersey". www.history.com. History Channel. Retrieved March 8, 2016.

- ↑ Shepherd, Joshua (April 15, 2014). ""Cursedly Thrashed": The Battle Of Harlem Heights". Journal of the American Revolution. Retrieved March 9, 2016.

- ↑ "The Battle of White Plains". www.theamericanrevolution.org. TheAmericanRevolution.org. Retrieved March 9, 2016.

- 1 2 Borkow, Richard (July 2013). "Westchester County, New York and the Revolutionary War: The Battle of White Plains (1776)". Westchester Magazine. Retrieved March 10, 2016.

- 1 2 Ayers, Edward L.; Gould, Lewis L.; Oshinky, David M.; Soderlund, Jean R. (2009). American Passage: A History of the United States (4th ed.). Boston, MA: Wadsworth, Cengage Learning. ISBN 9780547166292.

- 1 2 3 Mark, Steven Paul (November 20, 2013). "Too Little, Too Late: Battle Of The Hudson Highlands". Journal of the American Revolution. Retrieved March 10, 2016.

- ↑ Harrington, Hugh T. (September 25, 2014). "he Great West Point Chain". Journal of the American Revolution. Retrieved March 10, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 "Battle of Saratoga". www.wpi.edu. Worcester Polytechnic Institute. Retrieved March 10, 2016.

- 1 2 3 Stambach, Abigail; Stambach, Paul. "Victory...Impossible Without Schuyler’s Direction". dmna.ny.gov. New York State Military Museum. Retrieved March 10, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 "History and Culture". www.nps.gov. National Park Service. Retrieved March 10, 2016.

- ↑ Randall, Willard Sterne (1990). Benedict Arnold: Patriot and Traitor. William Morrow and Inc. pp. 522–523. ISBN 1-55710-034-9.

- ↑ Adams, Arthur, The Hudson River Guidebook (Fordham University Press, New York, 1996, pp. 146)

- 1 2 Lossing, Benson John (1852). The Pictorial Field-book of the Revolution. Harper & Brothers.

- 1 2 "Canal History". www.canals.ny.gov. New York State Canal Corporation. Retrieved March 6, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Canal Era". www.ushistory.org/. U.S. History. Retrieved March 6, 2016.

- 1 2 "Erie Canalway". www.eriecanalway.org. Erie Canalway. Retrieved March 7, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Finch, Roy G. "The Story of the New York State Canals" (PDF). www.canals.ny.gov. New York State Canals Corporation. Retrieved March 7, 2016.

- ↑ Levine, David (August 2010). "How the Delaware & Hudson Canal Fueled the Valley". Hudson Valley Magazine. Retrieved March 7, 2016.

- ↑ University of Rochester Chronology

- ↑ Kornhauser, Elizabeth Mankin; Ellis, Amy; Miesmer, Maureen (2003). Hudson River School: Masterworks from the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art. Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art. p. vii. Retrieved June 26, 2016.

- ↑ "The Panoramic River: the Hudson and the Thames". Hudson River Museum. 2013. p. 188. ISBN 978-0-943651-43-9. Retrieved June 23, 2016.

- ↑ "The Hudson River School: Nationalism, Romanticism, and the Celebration of the American Landscape". Virginia Tech History Department. Retrieved June 26, 2016.

- ↑ Nicholson, Louise (January 19, 2015). "East meets West: The Hudson River School at LACMA". Apollo. Retrieved June 23, 2016.

- ↑ Oelschlaeger, Max. "The Roots of Preservation: Emerson, Thoreau, and the Hudson River School". Nature Transformed. National Humanities Center. Retrieved June 26, 2016.

- ↑ Marter, Joan (2011). The Grove Encyclopedia of American Art. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. pp. 112–113. ISBN 978-0-19-533579-8. Retrieved June 26, 2016.

- 1 2 Avery, Kevin J. (October 2004). "The Hudson River School". Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved June 26, 2016.

- 1 2 O'Toole, Judith H. (2005). Different Views in Hudson River School Painting. Columbia University Press. p. 11.

- ↑ Boyle, Alexander. "Thomas Cole (1801-1848) The Dawn of the Hudson River School". Hamilton Auction Galleries. Retrieved 19 December 2012.

- ↑ "Asher B. Durand". Smithsonian American Art Museum: Renwick Gallery. Smithsonian Museum. Retrieved June 26, 2016.

- ↑ "The Hudson River Guide". www.offshoreblue.com. Blue Seas. Retrieved March 4, 2016.

- ↑ Harmon, Daniel E. (2004). "The Hudson River". Chelsea House Publishers. Retrieved June 23, 2016.

- ↑ Hunter, Louis C. (1985). A History of Industrial Power in the United States, 1730–1930, Vol. 2: Steam Power. Charlottesville, Virginia: University Press of Virginia.

- ↑ "Adirondack Journal — An Adirondack Presidential History". www.adkmuseum.org. Adirondack Museum. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- ↑ "Roosevelt-Marcy Byway". www.dot.ny.gov. NewState Department of Transportation. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- ↑ Sparling, Reed (Spring 2010). "More than the Wright stuff: Glenn Curtiss’ 1910 Hudson Flight" (PDF). The Hudson Valley Regional Review: A Journal of Regional Studies. Marist College. 26 (10): 1–4. Retrieved June 7, 2017.

- ↑ "Governor Signs River Road Bill; Overrides Protests Against Hudson Expressway". The New York Times. May 30, 1965. Retrieved June 26, 2016.

- ↑ New York State Museum - "Swim for the River"

- ↑ Turner, Celia. "US Airways Flight 1549 Crew receive prestigious Guild of Air Pilots and Air Navigators Award" (PDF). Guild of Air Pilots and Air Navigators. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 22, 2009. Retrieved April 30, 2014.

- ↑ Olshan, Jeremy; Livingston, Ikumulisa (January 17, 2009). "Quiet Air Hero is Captain America". New York Post. Retrieved February 12, 2009.

- ↑ Rogers, Katie (November 22, 2016). "A Whale Takes Up Residence in the Hudson River". The New York Times. Retrieved March 24, 2017.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hudson River. |

- Hudson River Maritime Museum

- Beczak Environmental Education Center

- Tocqueville in Newburgh — a Alexis de Tocqueville Tour segment on Hudson River steamship travel in the 1830s