History of Spain

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Spain |

.svg.png) |

| Timeline |

|

|

The history of Spain dates back to the Early Middle Ages. In 1516, Habsburg Spain unified a number of disparate predecessor kingdoms; its modern form of a constitutional monarchy was introduced in 1813, and the current democratic constitution dates to 1978.

After the completion of the Reconquista, the kingdoms of Spain were united under Habsburg rule in 1516. At the same time, the Spanish Empire began to expand to the New World across the ocean, marking the beginning of the Golden Age of Spain, during which, from the early 1500s to the 1650s, Habsburg Spain was among the most powerful states in the world.

During this period, Spain was involved in all major European wars, including the Italian Wars, the Eighty Years' War, the Thirty Years' War, and the Franco-Spanish War. In the later 17th century, however, Spanish power began to decline, and after the death of the last Habsburg ruler, the War of the Spanish Succession ended with the relegation of Spain, now under Bourbon rule, to the status of a second-rate power with a reduced influence in European affairs. The so-called Bourbon Reforms attempted the renewal of state institutions, with some success, but as the century ended, instability set in with the French Revolution and the Peninsular War, so that Spain never regained its former strength.

Fragmented by the war, Spain at the beginning of the 19th century was destabilised as different political parties representing "liberal", "reactionary", and "moderate" groups throughout the remainder of the century fought for and won short-lived control without any being sufficiently strong to bring about lasting stability. The former Spanish Empire overseas quickly disintegrated with the Latin American wars of independence and eventually the loss of what old colonies remained in the Spanish–American War of 1898.

A tenuous balance between liberal and conservative forces was struck in the establishment of constitutional monarchy during 1874–1931 but brought no lasting solution, and Spain descended into Civil War between the Republican and the Nationalist factions.

The war ended in a nationalist dictatorship, led by Francisco Franco, which controlled the Spanish government until 1975. The post-war decades were relatively stable (with the notable exception of an armed independence movement in the Basque Country), and the country experienced rapid economic growth in the 1960s and early 1970s.

Only with the death of Franco in 1975 did Spain return to Bourbon constitutional monarchy headed by Prince Juan Carlos and to democracy. Spain entered the European Economic Community in 1986 (transformed into the European Union with the Maastricht Treaty of 1992), and the Eurozone in 1999. The financial crisis of 2007–08 ended a decade of economic boom and Spain entered a recession and debt crisis and remains plagued by very high unemployment and a weak economy.

Spain is ranked as a middle power able to exert regional influence but unlike other powers with similar status (such as Germany, Italy and Japan) it is not part of the G8 and participates in the G20 only as a guest. Spain is part of the G6.

Prehistory

The Iberian Peninsula was first inhabited by anatomically modern humans about 32,000 years BP.

The earliest record of hominids living in Western Europe has been found in the Spanish cave of Atapuerca; a flint tool found there dates from 1.4 million years ago,[1] and early human fossils date to roughly 1.2 million years ago.[2] Modern humans in the form of Cro-Magnons began arriving in the Iberian Peninsula from north of the Pyrenees some 35,000 years ago. The most conspicuous sign of prehistoric human settlements are the famous paintings in the northern Spanish cave of Altamira, which were done c. 15,000 BC and are regarded as paramount instances of cave art.[3]

Furthermore, archeological evidence in places like Los Millares and El Argar, both in the province of Almería, and La Almoloya near Murcia suggests developed cultures existed in the eastern part of the Iberian Peninsula during the late Neolithic and the Bronze Age.[4]

Spanish prehistory extends to the pre-Roman Iron Age cultures that controlled most of Iberia: those of the Iberians, Celtiberians, Tartessians, Lusitanians, and Vascones and trading settlements of Phoenicians, Carthaginians, and Greeks on the Mediterranean coast.

Early history of the Iberian Peninsula

Before the Roman conquest the major cultures along the Mediterranean coast were the Iberians, the Celts in the interior and north-west, the Lusitanians in the west, and the Tartessians in the southwest. The seafaring Phoenicians, Carthaginians, and Greeks successively established trading settlements along the eastern and southern coast. The first Greek colonies, such as Emporion (modern Empúries), were founded along the northeast coast in the 9th century BC, leaving the south coast to the Phoenicians.[5]

The Greeks are responsible for the name Iberia, apparently after the river Iber (Ebro). In the 6th century BC, the Carthaginians arrived in Iberia, struggling first with the Greeks, and shortly after, with the newly arriving Romans for control of the Western Mediterranean. Their most important colony was Carthago Nova (Latin name of modern-day Cartagena).[5]

The peoples whom the Romans met at the time of their invasion in what is now known as Spain were the Iberians, inhabiting an area stretching from the northeast part of the Iberian Peninsula through the southeast. The Celts mostly inhabited the inner and north-west part of the peninsula. In the inner part of the peninsula, where both groups were in contact, a mixed culture arose, the Celtiberians. The Celtiberian Wars were fought between the advancing legions of the Roman Republic and the Celtiberian tribes of Hispania Citerior from 181 to 133 BC.[6][7] The Roman conquest of the peninsula was completed in 19 BC.

Roman Hispania

Hispania was the name used for the Iberian Peninsula under Roman rule from the 2nd century BC. The populations of the peninsula were gradually culturally Romanized,[8] and local leaders were admitted into the Roman aristocratic class.[9]

The Romans improved existing cities, such as Tarragona (Tarraco), and established others like Zaragoza (Caesaraugusta), Mérida (Augusta Emerita), Valencia (Valentia), León ("Legio Septima"), Badajoz ("Pax Augusta"), and Palencia.[10] The peninsula's economy expanded under Roman tutelage. Hispania supplied Rome with food, olive oil, wine and metal. The emperors Trajan, Hadrian, and Theodosius I, the philosopher Seneca, and the poets Martial, Quintilian, and Lucan were born in Hispania. Hispanic bishops held the Council of Elvira around 306.

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century, parts of Hispania came under the control of the Germanic tribes of Vandals, Suebi, and Visigoths.

The collapse of the Western Roman Empire did not lead to the same wholesale destruction of Western classical society as happened in areas like Roman Britain, Gaul and Germania Inferior during the Early Middle Ages, although the institutions and infrastructure did decline. Spain's present languages, its religion, and the basis of its laws originate from this period. The centuries of uninterrupted Roman rule and settlement left a deep and enduring imprint upon the culture of Spain.

Gothic Hispania (5th–8th centuries)

The first Germanic tribes to invade Hispania arrived in the 5th century, as the Roman Empire decayed.[11] The Visigoths, Suebi, Vandals and Alans arrived in Spain by crossing the Pyrenees mountain range, leading to the establishment of the Suebi Kingdom in Gallaecia, in the northwest, the Vandal Kingdom of Vandalusia (Andalusia), and the Visigothic Kingdom in Toledo. The Romanized Visigoths entered Hispania in 415. After the conversion of their monarchy to Roman Catholicism and after conquering the disordered Suebic territories in the northwest and Byzantine territories in the southeast, the Visigothic Kingdom eventually encompassed a great part of the Iberian Peninsula.[9][12]

As the Roman Empire declined, Germanic tribes invaded the former empire. Some were foederati, tribes enlisted to serve in Roman armies, and given land within the empire as payment, while others, such as the Vandals, took advantage of the empire's weakening defenses to seek plunder within its borders. Those tribes that survived took over existing Roman institutions, and created successor-kingdoms to the Romans in various parts of Europe. Iberia was taken over by the Visigoths after 410.[13]

At the same time, there was a process of "Romanization" of the Germanic and Hunnic tribes settled on both sides of the limes (the fortified frontier of the Empire along the Rhine and Danube rivers). The Visigoths, for example, were converted to Arian Christianity around 360, even before they were pushed into imperial territory by the expansion of the Huns.[14]

In the winter of 406, taking advantage of the frozen Rhine, refugees from (Germanic) Vandals and Sueves, and the (Sarmatian) Alans, fleeing the advancing Huns, invaded the empire in force. Three years later they crossed the Pyrenees into Iberia and divided the Western parts, roughly corresponding to modern Portugal and western Spain as far as Madrid, between them.[15]

The Visigoths, having sacked Rome two years earlier, arrived in the region in 412, founding the Visigothic kingdom of Toulouse (in the south of modern France) and gradually expanded their influence into the Iberian peninsula at the expense of the Vandals and Alans, who moved on into North Africa without leaving much permanent mark on Hispanic culture. The Visigothic Kingdom shifted its capital to Toledo and reached a high point during the reign of Leovigild.

Visigothic rule

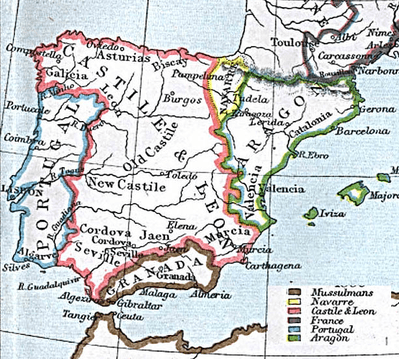

The Visigothic Kingdom conquered all of Hispania and ruled it until the early 8th century, when the peninsula fell to the Muslim conquests. The Muslim state in Iberia came to be known as Al-Andalus. After a period of Muslim dominance, the medieval history of Spain is dominated by the long Christian Reconquista or "reconquest" of the Iberian Peninsula from Muslim rule. The Reconquista gathered momentum during the 12th century, leading to the establishment of the Christian kingdoms of Portugal, Aragon, Castile and Navarre and by 1250, had reduced Muslim control to the Emirate of Granada in the south-east of the peninsula. Muslim rule in Granada survived until 1492, when it fell to the Catholic Monarchs.

Importantly, Spain never saw a decline in interest in classical culture to the degree observable in Britain, Gaul, Lombardy and Germany. The Visigoths, having assimilated Roman culture during their tenure as foederati, tended to maintain more of the old Roman institutions, and they had a unique respect for legal codes that resulted in continuous frameworks and historical records for most of the period between 415, when Visigothic rule in Spain began, and 711, when it is traditionally said to end. However, during the Visigothic dominion the cultural efforts made by the Franks and other Germanic tribes were not felt in the peninsula, nor achieved in the lesser kingdoms that emerged after the Muslim conquest.

The proximity of the Visigothic kingdoms to the Mediterranean and the continuity of western Mediterranean trade, though in reduced quantity, supported Visigothic culture. Arian Visigothic nobility kept apart from the local Catholic population. The Visigothic ruling class looked to Constantinople for style and technology while the rivals of Visigothic power and culture were the Catholic bishops – and a brief incursion of Byzantine power in Córdoba.

Spanish Catholic religion also coalesced during this time. The period of rule by the Visigothic Kingdom saw the spread of Arianism briefly in Spain.[16] The Councils of Toledo debated creed and liturgy in orthodox Catholicism, and the Council of Lerida in 546 constrained the clergy and extended the power of law over them under the blessings of Rome. In 587, the Visigothic king at Toledo, Reccared, converted to Catholicism and launched a movement in Spain to unify the various religious doctrines that existed in the land. This put an end to dissension on the question of Arianism. (For additional information about this period, see the History of Roman Catholicism in Spain.)

The Visigoths inherited from Late Antiquity a sort of feudal system in Spain, based in the south on the Roman villa system and in the north drawing on their vassals to supply troops in exchange for protection. The bulk of the Visigothic army was composed of slaves, raised from the countryside. The loose council of nobles that advised Spain's Visigothic kings and legitimized their rule was responsible for raising the army, and only upon its consent was the king able to summon soldiers.

The impact of Visigothic rule was not widely felt on society at large, and certainly not compared to the vast bureaucracy of the Roman Empire; they tended to rule as barbarians of a mild sort, uninterested in the events of the nation and economy, working for personal benefit, and little literature remains to us from the period. They did not, until the period of Muslim rule, merge with the Spanish population, preferring to remain separate, and indeed the Visigothic language left only the faintest mark on the modern languages of Iberia.[17]

The most visible effect was the depopulation of the cities as they moved to the countryside. Even while the country enjoyed a degree of prosperity when compared to the famines of France and Germany in this period, the Visigoths felt little reason to contribute to the welfare, permanency, and infrastructure of their people and state. This contributed to their downfall, as they could not count on the loyalty of their subjects when the Moors arrived in the 8th century.[17]

Islamic al-Andalus and the Christian Reconquest (8th–15th centuries)

The Arab Islamic conquest dominated most of North Africa by 710 AD. In 711 an Islamic Berber conquering party, led by Tariq ibn Ziyad, was sent to Iberia to intervene in a civil war in the Visigothic Kingdom. Tariq's army contained about 7,000 Berber horsemen, and Musa bin Nusayr is said to have sent an additional 5,000 reinforcements after the conquest.[18] Crossing the Strait of Gibraltar, they won a decisive victory in the summer of 711 when the Visigothic King Roderic was defeated and killed on July 19 at the Battle of Guadalete.

Tariq's commander, Musa, quickly crossed with Arab reinforcements, and by 718 the Muslims were in control of nearly the whole Iberian Peninsula. The advance into Western Europe was only stopped in what is now north-central France by the West Germanic Franks under Charles Martel at the Battle of Tours in 732.

A decisive victory for the Christians took place at Covadonga, in the north of the Iberian Peninsula, in the summer of 722. In a minor battle known as the Battle of Covadonga, a Muslim force sent to put down the Christian rebels in the northern mountains was defeated by Pelagius of Asturias, who established the monarchy of the Christian Kingdom of Asturias. In 739, a rebellion in Galicia, assisted by the Asturians, drove out Muslim forces and it joined the Asturian kingdom. The Kingdom of Asturias became the main base for Christian resistance to Islamic rule in the Iberian Peninsula for several centuries.

Caliph Al-Walid I had paid great attention to the expansion of an organized military, building the strongest navy in the Umayyad Caliphate era (the second major Arab dynasty after Mohammad and the first Arab dynasty of Al-Andalus). It was this tactic that supported the ultimate expansion to Spain. Caliph Al-Walid I's reign is considered as the apex of Islamic power, though Islamic power in Spain specifically climaxed in the 10th century under Abd-ar-Rahman III.[19]

Abbasids overthrow the Umayyad Caliphate

The rulers of Al-Andalus were granted the rank of Emir by the Umayyad Caliph Al-Walid I in Damascus. When the Abbasids overthrew the Umayyad Caliphate, Abd al-Rahman I managed to escape to al-Andalus. Once arrived, he declared al-Andalus independent. It is not clear if Abd al-Rahman considered himself to be a rival caliph, perpetuating the Umayyad Caliphate, or merely an independent Emir. The state founded by him is known as the Emirate of Cordoba. Al-Andalus was rife with internal conflict between the Islamic Umayyad rulers and people and the Christian Visigoth-Roman leaders and people.

In the 10th century Abd-ar-Rahman III declared the Caliphate of Córdoba, effectively breaking all ties with the Egyptian and Syrian caliphs. The Caliphate was mostly concerned with maintaining its power base in North Africa, but these possessions eventually dwindled to the Ceuta province. The first navy of the Emir of Córdoba was built after the humiliating Viking ascent of the Guadalquivir in 844 when they sacked Seville.[20]

In 942, pagan Magyars raided northern Spain.[20] Meanwhile, a slow but steady migration of Christian subjects to the northern kingdoms in Christian Hispania was slowly increasing the latter's power. Even so, Al-Andalus remained vastly superior to all the northern kingdoms combined in population, economy and military might; and internal conflict between the Christian kingdoms contributed to keep them relatively harmless.

Al-Andalus coincided with La Convivencia, an era of relative religious tolerance, and with the Golden age of Jewish culture in the Iberian Peninsula. (See: Emir Abd-ar-Rahman III 912; the Granada massacre 1066).[21]

Warfare between Muslims and Christians

Muslim interest in the peninsula returned in force around the year 1000 when Al-Mansur (also known as Almanzor) sacked Barcelona in 985. Under his son, other Christian cities were subjected to numerous raids.[22] After his son's death, the caliphate plunged into a civil war and splintered into the so-called "Taifa Kingdoms". The Taifa kings competed against each other not only in war but also in the protection of the arts, and culture enjoyed a brief upswing.

Medieval Spain was the scene of almost constant warfare between Muslims and Christians. The Almohads, who had taken control of the Almoravids' Maghribi and al-Andalus territories by 1147, surpassed the Almoravides in fundamentalist Islamic outlook, and they treated the non-believer dhimmis harshly. Faced with the choice of death, conversion, or emigration, many Jews and Christians left.[23]

By the mid-13th century, the Emirate of Granada was the only independent Muslim realm in Spain, which would last until 1492. Despite the decline in Muslim-controlled kingdoms, it is important to note the lasting effects exerted on the peninsula by Muslims in technology, culture, and society.

The Taifa kingdoms lost ground to the Christian realms in the north. After the loss of Toledo in 1085, the Muslim rulers reluctantly invited the Almoravides, who invaded Al-Andalus from North Africa and established an empire. In the 12th century the Almoravid empire broke up again, only to be taken over by the Almohad invasion, who were defeated by an alliance of the Christian kingdoms in the decisive battle of Las Navas de Tolosa in 1212. By 1250, nearly all of Iberia was back under Christian rule with the exception of the Muslim kingdom of Granada.

The Kings of Aragón ruled territories that consisted of not only the present administrative region of Aragon but also Catalonia, and later the Balearic Islands, Valencia, Sicily, Naples and Sardinia (see Crown of Aragon). Considered by most to have been the first mercenary company in Western Europe, the Catalan Company proceeded to occupy the Duchy of Athens, which they placed under the protection of a prince of the House of Aragon and ruled until 1379.[24]

The Spanish language and universities

In the 13th century, many languages were spoken in the Christian kingdoms of Iberia. These were the Latin-based Romance languages of Castilian, Aragonese, Catalan, Galician, Aranese, Asturian and Leonese, and the ancient language isolate of Basque. Throughout the century, Castilian (what is also known today as Spanish) gained a growing prominence in the Kingdom of Castile as the language of culture and communication, at the expense of Leonese and of other close dialects.

One example of this is the oldest preserved Castilian epic poem, Cantar de Mio Cid, written about the military leader El Cid. In the last years of the reign of Ferdinand III of Castile, Castilian began to be used for certain types of documents, and it was during the reign of Alfonso X that it became the official language. Henceforth all public documents were written in Castilian; likewise all translations were made into Castilian instead of Latin.

At the same time, Catalan and Galician became the standard languages in their respective territories, developing important literary traditions and being the normal languages in which public and private documents were issued: Galician from the 13th to the 16th century in Galicia and nearby regions of Asturias and Leon,[25] and Catalan from the 12th to the 18th century in Catalonia, the Balearic Islands and Valencia, where it was known as Valencian. Both languages were later substituted in its official status by Castilian Spanish, till the 20th century.

In the 13th century many universities were founded in León and in Castile. Some, such as the Leonese Salamanca and the Castilian Palencia, were among the earliest universities in Europe.

In 1492, under the Catholic Monarchs, the first edition of the Grammar of the Castilian Language by Antonio de Nebrija was published.

Early Modern Spain

Dynastic union

In the 15th century, the most important among all of the separate Christian kingdoms that made up the old Hispania were the Kingdom of Castile (occupying northern and central portions of the Iberian Peninsula), the Kingdom of Aragon (occupying northeastern portions of the peninsula), and the Kingdom of Portugal occupying the far western Iberian Peninsula. The rulers of the kingdoms of Castile and Aragon were allied with dynastic families in Portugal, France, and other neighboring kingdoms.

The death of King Henry IV of Castile in 1474 set off a struggle for power called the War of the Castilian Succession (1475–79). Contenders for the throne of Castile were Henry's one-time heir Joanna la Beltraneja, supported by Portugal and France, and Henry's half-sister Queen Isabella I of Castile, supported by the Kingdom of Aragon and by the Castilian nobility.

Isabella retained the throne and ruled jointly with her husband, King Ferdinand II. Isabella and Ferdinand had married in 1469[26] in Valladolid. Their marriage united both crowns and set the stage for the creation of the Kingdom of Spain, at the dawn of the modern era. That union, however, was a union in title only, as each region retained its own political and judicial structure. Pursuant to an agreement signed by Isabella and Ferdinand on January 15, 1474,[27] Isabella held more authority over the newly unified Spain than her husband, although their rule was shared.[27] Together, Isabella of Castile and Ferdinand of Aragon were known as the "Catholic Monarchs" (Spanish: los Reyes Católicos), a title bestowed on them by Pope Alexander VI.

Conclusion of the Reconquista and start of the Spanish Inquisition

The monarchs oversaw the final stages of the Reconquista of Iberian territory from the Moors with the conquest of Granada, conquered the Canary Islands, and expelled the Jews from Spain under the Alhambra Decree. Although until the 13th century religious minorities (Jews and Muslims) had enjoyed considerable tolerance in Castile and Aragon – the only Christian kingdoms where Jews were not restricted from any professional occupation – the situation of the Jews collapsed over the 14th century, reaching a climax in 1391 with large scale massacres in every major city except Ávila.

Over the next century, half of the estimated 80,000 Spanish Jews converted to Christianity (becoming "conversos"). The final step was taken by the Catholic Monarchs, who, in 1492, ordered the remaining Jews to convert or face expulsion from Spain. Depending on different sources, the number of Jews actually expelled, traditionally estimated at 120,000 people, is now believed to have numbered about 40,000.

Over the following decades, Muslims faced the same fate; and about 60 years after the Jews, they were also compelled to convert ("Moriscos") or be expelled. However, sufficient numbers of Moriscos stayed that Muslim culture remained influential in Spain. Jews and Muslims were not the only people to be persecuted during this time period. All Roma (Gitano, Gypsy) males between the ages of 18 and 26 were forced to serve in galleys – which was equivalent to a death sentence – but the majority managed to hide and avoid arrest.

Isabella and Ferdinand authorized the 1492 expedition of Christopher Columbus, who became the first known European to reach the New World since Leif Ericson. This and subsequent expeditions led to an influx of wealth into Spain, supplementing income from within Castile for the state that would prove to be a dominant power of Europe for the next two centuries.

Isabella ensured long-term political stability in Spain by arranging strategic marriages for each of her five children. Her firstborn, a daughter named Isabella, married Afonso of Portugal, forging important ties between these two neighboring countries and hopefully ensuring future alliance, but Isabella soon died before giving birth to an heir. Juana, Isabella's second daughter, married into the Habsburg dynasty when she wed Philip the Fair, the son of Maximilian I, King of Bohemia (Austria) and likely heir to the crown of the Holy Roman Emperor.

This ensured an alliance with the Habsburgs and the Holy Roman Empire, a powerful, far-reaching territory that assured Spain's future political security. Isabella's only son, Juan, married Margaret of Austria, further strengthening ties with the Habsburg dynasty. Isabella's fourth child, Maria, married Manuel I of Portugal, strengthening the link forged by her older sister's marriage. Her fifth child, Catherine, married King Henry VIII of England and was mother to Queen Mary I of England.

Imperial Spain

The Spanish Empire was one of the first modern global empires. It was also one of the largest empires in world history. In the 16th century, Spain and Portugal were in the vanguard of European global exploration and colonial expansion. The two kingdoms on the conquest and Iberian Peninsula competed with each other in opening of trade routes across the oceans. Spanish imperial conquest and colonization began with two Castilian expeditions. The first was an expedition to the Canary Islands in 1312 of a Castilian fleet led by a Genoese, Lancelotto Malocello. The second was another expedition to the Canaries in 1402 led by French adventurers, Jean de Béthencourt, Lord of Grainville in Normandy and Gadifer de la Salle of Poitou,[28] which began the Castilian conquest of the Canary Islands, completed in 1495.

In the 15th and 16th centuries, trade flourished across the Atlantic between Spain and the Americas and across the Pacific between East Asia and Mexico via the Philippines. Conquistadors deposed the Aztec, Inca and Maya governments with extensive help from local factions and laid claim to vast stretches of land in North and South America.

This New World empire was at first a disappointment, as the natives had little to trade, though settlement did encourage trade. Diseases such as smallpox and measles that arrived with the colonizers devastated the native populations, especially in the densely populated regions of the Aztec, Maya and Inca civilizations, and this reduced the economic potential of conquered areas.[29]

In the 1520s, large-scale extraction of silver from the rich deposits of Mexico's Guanajuato began to be greatly augmented by the silver mines in Mexico's Zacatecas and Bolivia's Potosí from 1546. These silver shipments re-oriented the Spanish economy, leading to the importation of luxuries and grain. The resource-rich colonies of Spain thus caused large cash inflows for the country.[30] They also became indispensable in financing the military capability of Habsburg Spain in its long series of European and North African wars, though, with the exception of a few years in the 17th century, Spain itself (Castile in particular) was by far the most important source of revenue.

Spain enjoyed a cultural golden age in the 16th and 17th centuries. For a time, the Spanish Empire dominated the oceans with its experienced navy and ruled the European battlefield with its fearsome and well trained infantry, the famous tercios, in the words of the prominent French historian Pierre Vilar, "enacting the most extraordinary epic in human history".

The financial burden within the peninsula was on the backs of the peasant class while the nobility enjoyed an increasingly lavish lifestyle. From the time beginning with the incorporation of the Portuguese Empire in 1580 (lost in 1640) until the loss of its North and South American colonies in the 19th century, Spain maintained the largest empire in the world even though it suffered fluctuating military and economic fortunes from the 1640s.

Confronted by the new experiences, difficulties and suffering created by empire-building, Spanish thinkers formulated some of the first modern thoughts on natural law, sovereignty, international law, war, and economics; there were even questions about the legitimacy of imperialism – in related schools of thought referred to collectively as the School of Salamanca. Despite these innovations, many motives for the empire were rooted in the Middle Ages. Religion played a very strong role in the spread of the Spanish empire. The thought that Spain could bring Christianity to the New World certainly played a strong role in the expansion of Spain's empire.

Spanish Kingdoms under the Habsburgs (16th–17th centuries)

Spain's world empire reached its greatest territorial extent in the late 18th century but it was under the Habsburg dynasty in the 16th and 17th centuries it reached the peak of its power and declined. When Spain's first Habsburg ruler Charles I became king of Spain in 1516, Spain became central to the dynastic struggles of Europe. After he became king of Spain, Charles also became Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor and because of his widely scattered domains was not often in Spain. As he approached the end of his life he made provision for the division of the Habsburg inheritance into two parts. On the one hand was Spain, its possessions in Europe, North Africa, the Americas and the Netherlands; on the other hand was the Holy Roman Empire. This was to create enormous difficulties for his son Philip II of Spain.

Philip II became king on Charles I's abdication in 1556. Spain largely escaped the religious conflicts that were raging throughout the rest of Europe and remained firmly Roman Catholic. Philip saw himself as a champion of Catholicism, both against the Muslim Ottoman Empire and the Protestant heretics.

In the 1560s, plans to consolidate control of the Netherlands led to unrest, which gradually led to the Calvinist leadership of the revolt and the Eighty Years' War. This conflict consumed much Spanish expenditure during the later 16th century. Conflicts included an attempt to conquer England – a cautious supporter of the Dutch – in the unsuccessful Spanish Armada, an early battle in the Anglo-Spanish War (1585–1604), and war with France (1590–98).

Despite these problems, the growing inflow of New World silver from mid-16th century, the justified military reputation of the Spanish infantry and even the navy quickly recovering from its Armada disaster, made Spain the leading European power, a novel situation of which its citizens were only just becoming aware. The Iberian Union with Portugal in 1580 not only unified the peninsula, but added that country's worldwide resources to the Spanish crown.

However, economic and administrative problems multiplied in Castile, and the weakness of the native economy became evident in the following century. Rising inflation, financially draining wars in Europe, the ongoing aftermath of the expulsion of the Jews and Moors from Spain, and Spain's growing dependency on the gold and silver imports, combined to cause several bankruptcies that caused economic crisis in the country, especially in heavily burdened Castile.

Barbary pirates from North Africa became an increasing problem. The coastal villages of Spain and of the Balearic Islands were frequently attacked. Formentera was even temporarily abandoned by its population. This occurred also along long stretches of the Spanish and Italian coasts, a relatively short distance across a calm sea from the pirates in their North African lairs. The most famous corsair was the Turkish Barbarossa ("Redbeard").[32] According to Robert Davis between 1 million and 1.25 million Europeans were captured by North African pirates and sold as slaves in North Africa and the Ottoman Empire between the 16th and 19th centuries. This was gradually alleviated as Spain and other Christian powers began to check Muslim naval dominance in the Mediterranean after the 1571 victory at Lepanto, but it would be a scourge that continued to afflict the country even in the next century.[32]

The great plague of 1596–1602 killed 600,000 to 700,000 people, or about 10% of the population. Altogether more than 1,250,000 deaths resulted from the extreme incidence of plague in 17th-century Spain.[33] Economically, the plague destroyed the labor force as well as creating a psychological blow to an already problematic Spain.[34]

Philip II died in 1598, and was succeeded by his son Philip III. In his reign (1598–1621) a ten-year truce with the Dutch was overshadowed in 1618 by Spain's involvement in the European-wide Thirty Years' War. Government policy was dominated by favorites, but it was also the period in which the geniuses of Cervantes and El Greco flourished.

Philip III was succeeded in 1621 by his son Philip IV of Spain (reigned 1621–65). Much of the policy was conducted by the minister Gaspar de Guzmán, Count-Duke of Olivares. In 1640, with the war in central Europe having no clear winner except the French, both Portugal and Catalonia rebelled. Portugal was lost to the crown for good; in Italy and most of Catalonia, French forces were expelled and Catalonia's independence was suppressed.

In the reign of Philip's developmentally disabled son and successor Charles II (1665–1700), Spain was essentially left leaderless and was gradually being reduced to a second-rank power.

The Habsburg dynasty became extinct in Spain with Charles II's death in 1700, and the War of the Spanish Succession ensued in which the other European powers tried to assume control of the Spanish monarchy. King Louis XIV of France eventually lost the War of the Spanish Succession, but because the victors' (Great Britain, the Dutch Republic and Austria) candidate for the Spanish throne (Archduke Charles of Austria) became Holy Roman Emperor, control of Spain was allowed to pass to the Bourbon dynasty. However, the peace deals that followed included relinquishing the right to unite the French and Spanish thrones and the partitioning of Spain's European empire.

The Golden Age (Siglo de Oro)

The Spanish Golden Age (in Spanish, Siglo de Oro) was a period of flourishing arts and letters in the Spanish Empire (now Spain and the Spanish-speaking countries of Latin America), coinciding with the political decline and fall of the Habsburgs (Philip III, Philip IV and Charles II). It is interesting to note how arts during the Golden Age flourished despite the decline of the empire in the 17th century. The last great writer of the age, Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, died in New Spain in 1695.[35]

The Habsburgs, both in Spain and Austria, were great patrons of art in their countries. El Escorial, the great royal monastery built by King Philip II, invited the attention of some of Europe's greatest architects and painters. Diego Velázquez, regarded as one of the most influential painters of European history and a greatly respected artist in his own time, cultivated a relationship with King Philip IV and his chief minister, the Count-Duke of Olivares, leaving us several portraits that demonstrate his style and skill. El Greco, a respected Greek artist from the period, settled in Spain, and infused Spanish art with the styles of the Italian renaissance and helped create a uniquely Spanish style of painting.

Some of Spain's greatest music is regarded as having been written in the period. Such composers as Tomás Luis de Victoria, Luis de Milán and Alonso Lobo helped to shape Renaissance music and the styles of counterpoint and polychoral music, and their influence lasted far into the Baroque period.

Spanish literature blossomed as well, most famously demonstrated in the work of Miguel de Cervantes, the author of Don Quixote de la Mancha. Spain's most prolific playwright, Lope de Vega, wrote possibly as many as one thousand plays over his lifetime, over four hundred of which survive to the present day.

Decline in the 17th century

The Spanish "Golden Age" politically ends no later than 1659, with the Treaty of the Pyrenees, ratified between France and Habsburg Spain. Spain had experienced severe financial difficulties in the later 16th century, that had caused the Spanish Crown to declare bankruptcy four times in the late 1500s (1557, 1560, 1576, 1596). However, the constant financial strain did not prevent the rise of Spanish power throughout the 16th century.

Many different factors, excessive warfare, inefficient taxation, a succession of weak kings in the 17th century, power struggles in the Spanish court contributed to the decline of the Habsburg Spain in the second half of the 17th century.

During the long regency for Charles II, the last of the Spanish Habsburgs, favouritism milked Spain's treasury, and Spain's government operated principally as a dispenser of patronage. Plague, famine, floods, drought, and renewed war with France wasted the country. The Peace of the Pyrenees (1659) had ended fifty years of warfare with France, whose king, Louis XIV, found the temptation to exploit a weakened Spain too great. Louis instigated the War of Devolution (1667–68) to acquire the Spanish Netherlands.

By the 17th century, the Catholic Church and Spain had showcased a close bond to one another, attesting to the fact that Spain was virtually free of Protestantism during the 16th century. In 1620, there were 100,000 Spaniards in the clergy, by 1660 there were about 200,000 Spaniards in the clergy and the Church owned 20% of all the land in Spain. The Spanish bureaucracy in this period was highly centralized, and totally reliant on the king for its efficient functioning. Under Charles II, the councils became the sinecures of wealthy aristocrats despite various attempt at reform. Political commentators in Spain, known as arbitristas, proposed a number of measures to reverse the decline of the Spanish economy, with limited success. In rural areas of Spain, heavy taxation of peasants reduced agricultural output as peasants in the countryside migrated to the cities. The influx of silver from the Americas has been cited as the cause of inflation, although only one fifth of the precious metal, i.e. the quinto real (royal fifth), actually went to Spain. A prominent internal factor was the Spanish economy's dependence on the export of luxurious Merino wool, which had its markets in northern Europe reduced by war and growing competition from cheaper textiles.

Spain under the Bourbons (18th century)

Charles II, having no direct heir, was succeeded by his great-nephew Philippe d'Anjou, a French prince, in 1700. Concern among other European powers that Spain and France united under a single Bourbon monarch would upset the balance of power led to the War of the Spanish Succession between 1701 and 1714. It pitted powerful France and fairly strong Spain against the Grand Alliance of England, Portugal, Savoy, the Netherlands and Austria.

After many battles, especially in Spain, the treaty of Utrecht recognised Philip, Duke of Anjou, Louis XIV's grandson, as King of Spain (as Philip V), thus confirming the succession stipulated in the will of the Charles II of Spain. However, Philip was compelled to renounce for himself and his descendants any right to the French throne, despite some doubts as to the lawfulness of such an act. Spain's Italian territories were apportioned.[36]

.jpg)

Philip V signed the Decreto de Nueva Planta in 1715. This new law revoked most of the historical rights and privileges of the different kingdoms that formed the Spanish Crown, especially the Crown of Aragon, unifying them under the laws of Castile, where the Castilian Cortes Generales had been more receptive to the royal wish.[37] Spain became culturally and politically a follower of absolutist France. Lynch says Philip V advanced the government only marginally over that of his predecessors and was more of a liability than the incapacitated Charles II; when a conflict came up between the interests of Spain and France, he usually favored France.[38]

Philip made reforms in government, and strengthened the central authorities relative to the provinces. Merit became more important, although most senior positions still went to the landed aristocracy. Below the elite level, inefficiency and corruption was as widespread as ever.

The reforms started by Philip V culminated in much more important reforms of Charles III.[38][39] However Israel argues that King Charles III cared little for the Enlightenment and his ministers paid little attention to the Enlightenment ideas influential elsewhere on the Continent. Israel says, "Only a few ministers and officials were seriously committed to enlightened aims. Most were first and foremost absolutists and their objective was always to reinforce monarchy, empire, aristocracy...and ecclesiastical control and authority over education."[40]

The economy, on the whole, improved over the depressed 1650–1700 era, with greater productivity and fewer famines and epidemics.[41]

The rule of the Spanish Bourbons continued under Ferdinand VI (1746–59) and Charles III (1759–88). Elisabeth of Parma, Philip V's widow, exerted great influence on Spain's foreign policy. Her principal aim was to have Spain's lost territories in Italy restored. She eventually received Franco-British support for this after the Congress of Soissons (1728–29).[42]

Under the rule of Charles III and his ministers – Leopoldo de Gregorio, Marquis of Esquilache and José Moñino, Count of Floridablanca – the economy improved. Fearing that Britain's victory over France in the Seven Years' War (1756–63) threatened the European balance of power, Spain allied itself to France but suffered a series of military defeats and ended up having to cede Florida to the British at the Treaty of Paris (1763) while gaining Louisiana from France. Spain regained Florida with the Treaty of Paris (1783), which ended the American Revolutionary War (1775–83), and gained an improved international standing.

However, there were no reforming impulses in the reign of Charles IV (1788 to abdication in 1808), seen by some as mentally handicapped. Dominated by his wife's lover, Manuel de Godoy, Charles IV embarked on policies that overturned much of Charles III's reforms. After briefly opposing Revolutionary France early in the French Revolutionary Wars, Spain was cajoled into an uneasy alliance with its northern neighbor, only to be blockaded by the British. Charles IV's vacillation, culminating in his failure to honour the alliance by neglecting to enforce the Continental System, led to the invasion of Spain in 1808 under Napoleon I, Emperor of the French, thereby triggering the Peninsular War, with enormous human and property losses, and loss of control over most of the overseas empire.

During most of the 18th century Spain had arrested its relative decline of the latter part of the 17th century. But despite the progress, it continued to lag in the political and mercantile developments then transforming other parts of Europe, most notably in Great Britain, the Low Countries, and France. The chaos unleashed by the Peninsular War caused this gap to widen greatly and Spain would not have an Industrial Revolution.

The Age of Enlightenment reached Spain in attenuated form about 1750. Attention focused on medicine and physics, with some philosophy. French and Italian visitors were influential but there was little challenge to Catholicism or the Church such as characterized the French philosophes. The leading Spanish figure was Benito Feijóo (1676–1764), a Benedictine monk and professor. He was a successful popularizer noted for encouraging scientific and empirical thought in an effort to debunk myths and superstitions. By the 1770s the conservatives had launched a counterattack and used censorship and the Inquisition to suppress Enlightenment ideas.[43]

At the top of the social structure of Spain in the 1780s stood the nobility and the church. A few hundred families dominated the aristocracy, with another 500,000 holding noble status. There were 200,000 church men and women, half of them in heavily endowed monasteries that controlled much of the land not owned by the nobles. Most people were on farms, either as landless peons or as holders of small properties. The small urban middle class was growing, but was distrusted by the landowners and peasants alike.[44]

19th century Spain

War of Spanish Independence (1808–14)

In the late 18th century, Bourbon-ruled Spain had an alliance with Bourbon-ruled France, and therefore did not have to fear a land war. Its only serious enemy was Britain, which had a powerful navy; Spain therefore concentrated its resources on its navy. When the French Revolution overthrew the Bourbons, a land war with France became a threat which the king tried to avoid. The Spanish army was ill-prepared. The officer corps was selected primarily on the basis of royal patronage, rather than merit. About a third of the junior officers had been promoted from the ranks, and they while they did have talent they had few opportunities for promotion or leadership. The rank-and-file were poorly trained peasants. Elite units included foreign regiments of Irishmen, Italians, Swiss, and Walloons, in addition to elite artillery and engineering units. Equipment was old-fashioned and in disrepair. The army lacked its own horses, oxen and mules for transportation, so these auxiliaries were operated by civilians, who might run away if conditions looked bad. In combat, small units fought well, but their old-fashioned tactics were hardly of use against the Napoleonic forces, despite repeated desperate efforts at last-minute reform.[45] When war broke out with France in 1808, the army was deeply unpopular. Leading generals were assassinated, and the army proved incompetent to handle command-and-control. Junior officers from peasant families deserted and went over to the insurgents; many units disintegrated. Spain was unable to mobilize its artillery or cavalry. In the war, there was one victory at the Battle of Bailén, and many humiliating defeats. Conditions steadily worsened, as the insurgents increasingly took control of Spain's battle against Napoleon. Napoleon ridiculed the army as "the worst in Europe"; the British who had to work with it agreed.[46] It was not the Army that defeated Napoleon, but the insurgent peasants whom Napoleon ridiculed as packs of "bandits led by monks" (they in turn believed Napoleon was the devil).[47] By 1812, the army controlled only scattered enclaves, and could only harass the French with occasional raids. The morale of the army had reached a nadir, and reformers stripped the aristocratic officers of most of their legal privileges.[48]

Spain initially sided against France in the Napoleonic Wars, but the defeat of her army early in the war led to Charles IV's pragmatic decision to align with the revolutionary French. Spain was put under a British blockade, and her colonies began to trade independently with Britain but it was the defeat of the British invasions of the Río de la Plata in South America (1806 and 1807) that emboldened independence and revolutionary hopes in Spain's North and South American colonies. A major Franco-Spanish fleet was lost at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805, prompting the vacillating king of Spain to reconsider his difficult alliance with Napoleon. Spain temporarily broke off from the Continental System, and Napoleon – aggravated with the Bourbon kings of Spain – invaded Spain in 1808 and deposed Ferdinand VII, who had been on the throne only forty-eight days after his father's abdication in March 1808. On July 20, 1808, Joseph Bonaparte, eldest brother of Napoleon Bonaparte, entered Madrid and established a government by which he became King of Spain, serving as a surrogate for Napoleon.[49]

The former Spanish king was dethroned by Napoleon, who put his own brother on the throne. Spaniards revolted. Thompson says the Spanish revolt was, "a reaction against new institutions and ideas, a movement for loyalty to the old order: to the hereditary crown of the Most Catholic kings, which Napoleon, an excommunicated enemy of the Pope, had put on the head of a Frenchman; to the Catholic Church persecuted by republicans who had desecrated churches, murdered priests, and enforced a "loi des cultes"; and to local and provincial rights and privileges threatened by an efficiently centralized government.[50] Juntas were formed all across Spain that pronounced themselves in favor of Ferdinand VII. On September 26, 1808, a Central Junta was formed in the town of Aranjuez to coordinate the nationwide struggle against the French. Initially, the Central Junta declared support for Ferdinand VII, and convened a "General and Extraordinary Cortes" for all the kingdoms of the Spanish Monarchy. On February 22 and 23, 1809, a popular insurrection against the French occupation broke out all over Spain.[51]

The peninsular campaign was a disaster for France. Napoleon did well when he was in direct command, but that followed severe losses, and when he left in 1809 conditions grew worse for France. Vicious reprisals, famously portrayed by Goya in "The Disasters of War", only made the Spanish guerrillas angrier and more active; the war in Spain proved to be a major, long-term drain on French money, manpower and prestige.[52]

In March 1812, the Cádiz Cortes created the first modern Spanish constitution, the Constitution of 1812 (informally named La Pepa). This constitution provided for a separation of the powers of the executive and the legislative branches of government. The Cortes was to be elected by universal suffrage, albeit by an indirect method. Each member of the Cortes was to represent 70,000 people. Members of the Cortes were to meet in annual sessions. The King was prevented from either convening or proroguing the Cortes. Members of the Cortes were to serve single two-year terms. They could not serve consecutive terms; a member could serve a second term only by allowing someone else to serve a single intervening term in office. This attempt at the development of a modern constitutional government lasted from 1808 until 1814.[53] Leaders of the liberals or reformist forces during this revolution were José Moñino, Count of Floridablanca, Gaspar Melchor de Jovellanos and Pedro Rodríguez, Conde de Campomanes. Born in 1728, Floridablanca was eighty years of age at the time of the revolutionary outbreak in 1808. He had served as Prime Minister under King Charles III of Spain from 1777 until 1792; However, he tended to be suspicious of the popular spontaneity and resisted a revolution.[54] Born in 1744, Jovellanos was somewhat younger than Floridablanco. A writer and follower of the philosophers of the Enlightenment tradition of the previous century, Jovellanos had served as Minister of Justice from 1797 to 1798 and now commanded a substantial and influential group within the Central Junta. However, Jovellanos had been imprisoned by Manuel de Godoy, Duke of Alcudia, who had served as the prime minister, virtually running the country as a dictator from 1792 until 1798 and from 1801 until 1808. Accordingly, even Jovellanos tended to be somewhat overly cautious in his approach to the revolutionary upsurge that was sweeping Spain in 1808.[55]

The Spanish army was stretched as it fought Napoleon's forces because of a lack of supplies and too many untrained recruits, but at Bailén in June 1808, the Spanish army inflicted the first major defeat suffered by a Napoleonic army; this resulted in the collapse of French power in Spain. Napoleon took personal charge and with fresh forces reconquered Spain in a matter of months, defeating the Spanish and British armies in a brilliant campaign of encirclement. After this the Spanish armies lost every battle they fought against the French imperial forces but were never annihilated; after battles they would retreat into the mountains to regroup and launch new attacks and raids. Guerrilla forces sprang up all over the country and, with the army, tied down huge numbers of Napoleon's troops, making it difficult to sustain concentrated attacks on enemy forces. The attacks and raids of the Spanish army and guerrillas became a massive drain on Napoleon's military and economic resources.[56] In this war, Spain was aided by the British and Portuguese, led by the Duke of Wellington. The Duke of Wellington fought Napoleon's forces in the Peninsular War, with Joseph Bonaparte playing a minor role as king at Madrid. The brutal war was one of the first guerrilla wars in modern Western history. French supply lines stretching across Spain were mauled repeatedly by the Spanish armies and guerrilla forces; thereafter, Napoleon's armies were never able to control much of the country. The war fluctuated, with Wellington spending several years behind his fortresses in Portugal while launching occasional campaigns into Spain.[57]

After Napoleon's disastrous 1812 campaign in Russia, Napoleon began to recall his forces for the defence of France against the advancing Russian and other coalition forces, leaving his forces in Spain increasingly undermanned and on the defensive against the advancing Spanish, British and Portuguese armies. At the Battle of Vitoria in 1813, an allied army under the Duke of Wellington decisively defeated the French and in 1814 Ferdinand VII was restored as King of Spain.[58][59]

Loss of North and South American colonies

Spain lost all of its North and South American colonies, except Cuba and Puerto Rico, in a complex series of revolts 1808–26.[60][61] Spain was at war with Britain 1798–1808, and the British Navy cut off its ties to its colonies. Trade was handled by American and Dutch traders. The colonies thus had achieved economic independence from Spain, and set up temporary governments or juntas which were generally out of touch with the mother country. After 1814, as Napoleon was defeated and Ferdinand VII was back on the throne, the king sent armies to regain control and reimpose autocratic rule. In the next phase 1809–16, Spain defeated all the uprising. A second round 1816–25 was successful and drove the Spanish out of all of its mainland holdings. Spain had no help from European powers. Indeed, Britain (and the United States) worked against it. When they were cut off from Spain, the colonies saw a struggle for power between Spaniards who were born in Spain (called "peninsulares") and those of Spanish descent born in New Spain (called "creoles"). The creoles were the activists for independence. Multiple revolutions enabled the colonies to break free of the mother country. In 1824 the armies of generals José de San Martín of Argentina and Simón Bolívar of Venezuela defeated the last Spanish forces; the final defeat came at the Battle of Ayacucho in southern Peru. After that Spain played a minor role in international affairs. Business and trade in the ex-colonies were under British control. Spain kept only Cuba and Puerto Rico in the New World.[62]

Reaction and change (1814–73)

Although the juntas, that had forced the French to leave Spain, had sworn by the liberal Constitution of 1812, Ferdinand VII had the support of conservatives and he rejected it.[63] He ruled in the authoritarian fashion of his forebears.[64]

The government, nearly bankrupt, was unable to pay her soldiers. There were few settlers or soldiers in Florida, so it was sold to the United States for 5 million dollars. In 1820, an expedition intended for the colonies revolted in Cadiz. When armies throughout Spain pronounced themselves in sympathy with the revolters, led by Rafael del Riego, Ferdinand relented and was forced to accept the liberal Constitution of 1812. This was the start of the second bourgeois revolution in Spain, which would last from 1820 to 1823.[59] Ferdinand himself was placed under effective house arrest for the duration of the liberal experiment.

The tumultuous three years of liberal rule that followed (1820–23) were marked by various absolutist conspiracies. The liberal government, which reminded European statesmen entirely too much of the governments of the French Revolution, was viewed with hostility by the Congress of Verona in 1822, and France was authorized to intervene. France crushed the liberal government with massive force in the so-called "Hundred Thousand Sons of Saint Louis" expedition, and Ferdinand was restored as absolute monarch in 1823. In Spain proper, this marked the end of the second Spanish bourgeois revolution.

.jpg)

In Spain, the failure of the second bourgeois revolution was followed by a period of uneasy peace for the next decade. Having borne only a female heir presumptive, it appeared that Ferdinand would be succeeded by his brother, Infante Carlos of Spain. While Ferdinand aligned with the conservatives, fearing another national insurrection, he did not view Carlos's reactionary policies as a viable option. Ferdinand – resisting the wishes of his brother – decreed the Pragmatic Sanction of 1830, enabling his daughter Isabella to become Queen. Carlos, who made known his intent to resist the sanction, fled to Portugal.

Ferdinand's death in 1833 and the accession of Isabella II as Queen of Spain sparked the First Carlist War (1833–39). Isabella was only three years old at the time so her mother, Maria Cristina of Bourbon-Two Sicilies, was named regent until her daughter came of age. Carlos invaded the Basque country in the north of Spain and attracted support from absolutist reactionaries and conservatives; these forces were known as the "Carlist" forces. The supporters of reform and of limitations on the absolutist rule of the Spanish throne rallied behind Isabella and the regent, Maria Christina; these reformists were called "Cristinos." Though Cristino resistance to the insurrection seemed to have been overcome by the end of 1833, Maria Cristina's forces suddenly drove the Carlist armies from most of the Basque country. Carlos then appointed the Basque general Tomás de Zumalacárregui as his commander-in-chief. Zumalacárregui resuscitated the Carlist cause, and by 1835 had driven the Cristino armies to the Ebro River and transformed the Carlist army from a demoralized band into a professional army of 30,000 of superior quality to the government forces. Zumalacárregui's death in 1835 changed the Carlists' fortunes. The Cristinos found a capable general in Baldomero Espartero. His victory at the Battle of Luchana (1836) turned the tide of the war, and in 1839, the Convention of Vergara put an end to the first Carlist insurrection.[65]

The progressive General Espartero, exploiting his popularity as a war hero and his sobriquet "Pacifier of Spain", demanded liberal reforms from Maria Cristina. The Queen Regent, who resisted any such idea, preferred to resign and let Espartero become regent instead in 1840. Espartero's liberal reforms were then opposed by moderates, and the former general's heavy-handedness caused a series of sporadic uprisings throughout the country from various quarters, all of which were bloodily suppressed. He was overthrown as regent in 1843 by Ramón María Narváez, a moderate, who was in turn perceived as too reactionary. Another Carlist uprising, the Matiners' War, was launched in 1846 in Catalonia, but it was poorly organized and suppressed by 1849.

Isabella II of Spain took a more active role in government after coming of age, but she was immensely unpopular throughout her reign (1833–68). She was viewed as beholden to whoever was closest to her at court, and the people of Spain believed that she cared little for them. As a result, there was another insurrection in 1854 led by General Domingo Dulce y Garay and General Leopoldo O'Donnell y Jarris. Their coup overthrew the dictatorship of Luis Jose Sartorius, 1st Count of San Luis. As the result of the popular insurrection, the Partido Progresista (Progressive Party) obtained widespread support in Spain and came to power in the government in 1854.[66] In 1856, Isabella attempted to form the Liberal Union, a pan-national coalition under the leadership of Leopoldo O'Donnell, who had already marched on Madrid that year and deposed another Espartero ministry. Isabella's plan failed and cost Isabella more prestige and favor with the people. In 1860, Isabella launched a successful war against Morocco, waged by generals O'Donnell and Juan Prim that stabilized her popularity in Spain. However, a campaign to reconquer Peru and Chile during the Chincha Islands War (1864–66) proved disastrous and Spain suffered defeat before the determined South American powers.

In 1866, a revolt led by Juan Prim was suppressed, but in 1868 there was a further revolt, known as the Glorious Revolution. The progresista generals Francisco Serrano and Juan Prim revolted against Isabella and defeated her moderado generals at the Battle of Alcolea (1868). Isabella was driven into exile in Paris.[67]

Two years of revolution and anarchy followed, until in 1870 the Cortes declared that Spain would again have a king. Amadeus of Savoy, the second son of King Victor Emmanuel II of Italy, was selected and duly crowned King of Spain early the following year.[68] Amadeus – a liberal who swore by the liberal constitution the Cortes promulgated – was faced immediately with the incredible task of bringing the disparate political ideologies of Spain to one table. The country was plagued by internecine strife, not merely between Spaniards but within Spanish parties.

First Spanish Republic (1873–74)

Following the Hidalgo affair and an army rebellion, Amadeus famously declared the people of Spain to be ungovernable, abdicated the throne, and left the country (11 February 1873).

In his absence, a government of radicals and Republicans was formed that declared Spain a republic. The First Spanish Republic (1873–74) was immediately under siege from all quarters. The Carlists were the most immediate threat, launching a violent insurrection after their poor showing in the 1872 elections. There were calls for socialist revolution from the International Workingmen's Association, revolts and unrest in the autonomous regions of Navarre and Catalonia, and pressure from the Catholic Church against the fledgling republic.[69]

The Restoration (1874–1931)

Although the former queen, Isabella II was still alive, she recognized that she was too divisive as a leader, and abdicated in 1870 in favor of her son, Alfonso.

Alfonso XII of Spain was duly crowned on 28 December 1874 after returning from exile. After the tumult of the First Spanish Republic, Spaniards were willing to accept a return to stability under Bourbon rule. The Republican armies in Spain – which were resisting a Carlist insurrection – pronounced their allegiance to Alfonso in the winter of 1874–75, led by Brigadier General Martínez-Campos. The Republic was dissolved and Antonio Cánovas del Castillo, a trusted advisor to the king, was named Prime Minister on New Year's Eve, 1874. The Carlist insurrection was put down vigorously by the new king, who took an active role in the war and rapidly gained the support of most of his countrymen.[70] A system of turnos was established in Spain in which the liberals, led by Práxedes Mateo Sagasta and the conservatives, led by Antonio Cánovas del Castillo, alternated in control of the government. A modicum of stability and economic progress was restored to Spain during Alfonso XII's rule (1874–85), although progress was cut short by his sudden death at age 28.

Constitutional monarchy continued under King Alfonso XIII.[71] Alfonso XIII was born after his father's death and was proclaimed king upon his birth. However, the government had become destabilized by Alfonso XII's unexpected death in 1885, followed by the assassination of prime minister Antonio Cánovas del Castillo in 1897. The reign of Alfonso XIII (1886–1931) saw the Spanish–American War of 1898, culminating in the loss of the Philippines plus Spain's last colonies in the Americas, Cuba and Puerto Rico; the "Great War" in Europe (now known as World War I, 1914–18), although Spain maintained neutrality throughout the conflict; the influenza pandemic nicknamed the Spanish Flu (1918–19); and the Rif War in Morocco (1920–26). His reign also saw the rise to dictatorship of General Miguel Primo de Rivera, who seized control of the government by military coup in 1923 and ruled as a dictator – with the monarch's support – for seven years (1923–30). The worldwide recession, marked first by the Wall Street Crash of 1929, caused deepening economic hardships in Spain and the resignation of Primo de Rivera's government in 1930. General elections were held in 1931 to replace the government, with Republican and anticlerical candidates winning the majority of votes. Alfonso XIII left the country in response to the proclamation of the Second Spanish Republic, although he never abdicated.

Disaster of 1898

Cuba rebelled against Spain in the Ten Years' War beginning in 1868, resulting in the abolition of slavery in Spain's colonies in the New World. American business interests in the island, coupled with concerns for the people of Cuba, aggravated relations between the two countries. The explosion of the USS Maine launched the Spanish–American War in 1898, in which Spain fared disastrously. Cuba gained its independence and Spain lost its remaining New World colony, Puerto Rico, which together with Guam and the Philippines were ceded to the United States for 20 million dollars. In 1899, Spain sold its remaining Pacific islands – the Northern Mariana Islands, Caroline Islands and Palau – to Germany and Spanish colonial possessions were reduced to Spanish Morocco, Spanish Sahara and Spanish Guinea, all in Africa.[72]

The "disaster" of 1898 created the Generation of '98, a group of statesmen and intellectuals who demanded liberal change from the new government. However both Anarchism on the left and fascism on the right grew rapidly in Spain in the early 20th century. A revolt in 1909 in Catalonia was bloodily suppressed.[73] Jensen (1999) argues that the defeat of 1898 led many military officers to abandon the liberalism that had been strong in the officer corps and turn to the right. They interpreted the American victory in 1898 as well as the Japanese victory against Russia in 1905 as proof of the superior value of willpower and moral values over technology. Over the next three decades, Jensen argues, these values shaped the outlook of Francisco Franco and other Falangists.[74]

20th century Spain

1914–31

Spain's neutrality in World War I allowed it to become a supplier of material for both sides to its great advantage, prompting an economic boom in Spain. The outbreak of Spanish influenza in Spain and elsewhere, along with a major economic slowdown in the postwar period, hit Spain particularly hard, and the country went into debt. A major workers' strike was suppressed in 1919.

Spanish colonial policies in Spanish Morocco led to an uprising known as the Rif War; rebels took control of most of the area except for the enclaves of Ceuta and Melilla in 1921. King Alfonso XIII decided to support the dictatorship of General Miguel Primo de Rivera in 1923. As Prime Minister Primo de Rivera promised to reform the country quickly and restore elections soon. He deeply believed that it was the politicians who had ruined Spain and that governing without them he could regenerate the nation. His slogan was "Country, Religion, Monarchy."

Spain (in joint action with France) won a decisive military victory in Morocco, (1925–26). The war had dragged on since 1917 and cost Spain $800 million.[75][76]

The late 1920s were prosperous until the worldwide Great Depression hit in 1929. In early 1930 bankruptcy and massive unpopularity forced the king to remove Primo de Rivera. Historians depict an idealistic but inept dictator who did not understand government, lacked clear ideas and showed very little political acumen. He consulted no one, had a weak staff, and made frequent strange pronouncements. He started with very broad support but lost every element until only the army was left. His projects ran large deficits which he kept hidden. His multiple repeated mistakes discredited the king and ruined the monarchy, while heightening social tensions that led in 1936 to a full-scale Spanish Civil War. Urban voters had lost faith in the king, and voted for republican parties in the municipal elections of April 1931. The king fled the country without abdicating and a republic was established.[77]

Second Spanish Republic (1931–36)

Political ideologies were intensely polarized, as both right and left saw vast evil conspiracies on the other side that had to be stopped. The central issue was the role of the Catholic Church, which the left saw as the major enemy of modernity and the Spanish people, and the right saw as the invaluable protector of Spanish values.[78]

Power seesawed back and forth, 1931–36, as the monarchy was overthrown and complex coalitions formed and fell apart. The end came in a devastating civil war, 1936–39, which was won by the conservative, pro-church, Army-backed “Nationalist” forces supported by Nazi Germany and Italy. The Nationalists, led by General Francisco Franco, defeated the Republican coalition of liberals, socialists, anarchists, and communists, which was backed by the Soviet Union.

Under the Second Spanish Republic, women were allowed to vote in general elections for the first time. The Republic devolved substantial autonomy to the Basque Country and to Catalonia.

The first governments of the Republic were center-left, headed by Niceto Alcalá-Zamora and Manuel Azaña. Economic turmoil, substantial debt, and fractious, rapidly changing governing coalitions led to escalating political violence and attempted coups by right and left.

In 1933, the right-wing Spanish Confederation of the Autonomous Right (CEDA), based on the Catholic vote, won power. An armed rising of workers in October 1934, which reached its greatest intensity in Asturias and Catalonia, was forcefully put down by the CEDA government. This in turn energized political movements across the spectrum in Spain, including a revived anarchist movement and new reactionary and fascist groups, including the Falange and a revived Carlist movement.[79]

Spanish Civil War (1936–39)

The Spanish Civil War was marked by numerous small battles and sieges, and many atrocities, until the rebels (the "Nationalists"), led by Francisco Franco, won in 1939. There was military intervention as Italy sent land forces, and Germany sent smaller elite air force and armored units to the rebel side (the Nationalists). The Soviet Union sold armaments to the "Loyalists" ("Republicans"), while the Communist parties in numerous countries sent soldiers to the "International Brigades." The civil war did not escalate into a larger conflict, but did become a worldwide ideological battleground that pitted the left and many liberals against Catholics and conservatives. Britain, France and the United States remained neutral and refused to sell military supplies. Worldwide there was a decline in pacifism and a growing sense that another world war was imminent, and that it would be worth fighting for.[80]

Political and military balance

In the 1930s, Spanish politics were polarized at the left and right extremes of the political spectrum. The left-wing favored class struggle, land reform to overthrow the land owners, autonomy to the regions, and the destruction of the Catholic Church. The right-wing groups, the largest of which was CEDA, a Catholic coalition, believed in tradition, stability and hierarchy. Religion was the main dividing line between right and left, but there were regional variations. The Basques were devoutly Catholic but they put a high priority on regional autonomy. The Left offered a better deal so in 1936–37 they fought for the Republicans. In 1937 they pulled out of the war.

The Spanish Republican government moved to Valencia, to escape Madrid, which was under siege by the Nationalists. It had some military strength in the Air Force and Navy, but it had lost nearly all of the regular Army. After opening the arsenals to give rifles, machine guns and artillery to local militias, it had little control over the Loyalist ground forces. Republican diplomacy proved ineffective, with only two useful allies, the Soviet Union and Mexico. Britain, France and 27 other countries had agreed to an arms embargo on Spain, and the United States went along. Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy both signed that agreement, but ignored it and sent supplies and vital help, including a powerful air force under German command, the Condor Legion. Tens of thousands of Italians arrived under Italian command. Portugal supported the Nationalists, and allowed the trans-shipment of supplies to Franco's forces. The Soviets sold tanks and other armaments for Spanish gold, and sent well-trained officers and political commissars. It organized the mobilization of tens of thousands of mostly communist volunteers from around the world, who formed the International Brigades.

In 1936, the Left united in the Popular Front and were elected to power. However, this coalition, dominated by the centre-left, was undermined both by the revolutionary groups such as the anarchist Confederación Nacional del Trabajo (CNT) and Federación Anarquista Ibérica (FAI) and by anti-democratic far-right groups such as the Falange and the Carlists. The political violence of previous years began to start again. There were gunfights over strikes; landless labourers began to seize land, church officials were killed and churches burnt. On the other side, right wing militias (such as the Falange) and gunmen hired by employers assassinated left wing activists. The Republican democracy never generated the consensus or mutual trust between the various political groups that it needed to function peacefully. As a result, the country slid into civil war. The right wing of the country and high ranking figures in the army began to plan a coup, and when Falangist politician José Calvo-Sotelo was shot by Republican police, they used it as a signal to act while the Republican leadership was confused and inert.[81][82]

Military operations

The Nationalists under Franco won the war, and historians continue to debate the reasons. The Nationalists were much better unified and led than the Republicans, who squabbled and fought amongst themselves endlessly and had no clear military strategy. The Army went over to the Nationalists, but it was very poorly equipped – there were no tanks or modern airplanes. The small navy supported the Republicans, but their armies were made up of raw recruits and they lacked both equipment and skilled officers and sergeants. Nationalist senior officers were much better trained and more familiar with modern tactics than the Republicans.[83]

On 17 July 1936, General Francisco Franco brought the colonial army stationed in Morocco to the mainland, while another force from the north under General Mola moved south from Navarre. Another conspirator, General Sanjurjo, who was in exile in Portugal, was killed in a plane crash while being brought to join the other military leaders. Military units were also mobilised elsewhere to take over government institutions. Franco intended to seize power immediately, but successful resistance by Republicans in the key centers of Madrid, Barcelona, Valencia, the Basque country, and other points meant that Spain faced a prolonged civil war. By 1937 much of the south and west was under the control of the Nationalists, whose Army of Africa was the most professional force available to either side. Both sides received foreign military aid: the Nationalists from Nazi Germany and Italy, while the Republicans were supported by organised far-left volunteers from the Soviet Union.

The Siege of the Alcázar at Toledo early in the war was a turning point, with the Nationalists winning after a long siege. The Republicans managed to hold out in Madrid, despite a Nationalist assault in November 1936, and frustrated subsequent offensives against the capital at Jarama and Guadalajara in 1937. Soon, though, the Nationalists began to erode their territory, starving Madrid and making inroads into the east. The North, including the Basque country fell in late 1937 and the Aragon front collapsed shortly afterwards. The bombing of Guernica on the afternoon of 26 April 1937 – a mission used as a testing ground for the German Luftwaffe's Condor Legion – was probably the most infamous event of the war and inspired Picasso's painting. The Battle of the Ebro in July–November 1938 was the final desperate attempt by the Republicans to turn the tide. When this failed and Barcelona fell to the Nationalists in early 1939, it was clear the war was over. The remaining Republican fronts collapsed, as civil war broke out inside the Left, as the Republicans suppressed the Communists. Madrid fell in March 1939.[84]

The war cost between 300,000 and 1,000,000 lives. It ended with the total collapse of the Republic and the accession of Francisco Franco as dictator of Spain. Franco amalgamated all right wing parties into a reconstituted fascist party Falange and banned the left-wing and Republican parties and trade unions. The Church was more powerful than it had been in centuries.[85]