History of education in the Indian subcontinent

The history of education in the South Asia began with teaching of traditional elements such as Indian religions, Indian mathematics, Indian logic at early Hindu and Buddhist centres of learning such as ancient Taxila (in modern-day Pakistan) and Nalanda (in India) before the common era. Islamic education became ingrained with the establishment of the Islamic empires in the Indian subcontinent in the Middle Ages while the coming of the Europeans later brought western education to colonial India. A series of measures continuing throughout the early half of the 20th century ultimately laid the foundation of education in the Republic of India, education in Pakistan and much of South Asia.

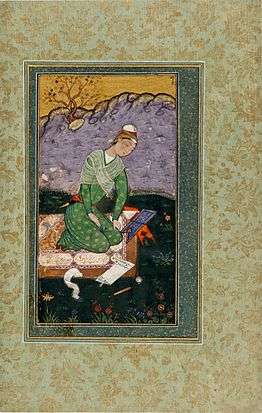

Early history

.jpg)

Early education in India commenced under the supervision of a guru/prabhu.[1] Initially, education was open to all and seen as one of the methods to achieve Moksha in those days, or enlightenment. As time progressed, due to superiority complexes, the education was imparted on the basis of caste and the related duties that one had to perform as a member of a specific caste.[1] The Brahmans learned about scriptures and religion while the Kshatriya were educated in the various aspects of warfare.[1] The Vaishya caste learned commerce and other specific vocational courses while education was largely denied to the Shudras, the lowest caste.[1] The earliest venues of education in India were often secluded from the main population.[1] Students were expected to follow strict monastic guidelines prescribed by the guru and stay away from cities in ashrams.[2] However, as population increased under the Gupta empire centres of urban learning became increasingly common and Cities such as Varanasi and the Buddhist centre at Nalanda became increasingly visible.[2]

Education in India is a piece of education traditional form was closely related to religion.[3] Among the Heterodox schools of belief were the Jain and Buddhist schools.[4] Heterodox Buddhist education was more inclusive and aside of the monastic orders the Buddhist education centres were urban institutes of learning such as Taxila and Nalanda where grammar, medicine, philosophy, logic, metaphysics, arts and crafts etc. were also taught.[1][2] Early secular Buddhist institutions of higher learning like Taxila and Nalanda continued to function well into the common era and were attended by students from China and Central Asia.[3]

On the subject of education for the nobility Joseph Prabhu writes: "Outside the religious framework, kings and princes were educated in the arts and sciences related to government: politics (danda-nıti), economics (vartta), philosophy (anvıksiki), and historical traditions (itihasa). Here the authoritative source was Kautilya’s Arthashastra, often compared to Niccolò Machiavelli’s The Prince for its worldly outlook and political scheming."[1] The Rgveda mentions female poets called brahmavadinis, specifically Lopamudra and Ghosha.[5] By 800 BCE women such as Gargi and Maitreyi were mentioned as scholars in the religious Upnishads.[5] Maya, mother of the historic Buddha, was an educated queen while other women in India contributed to writing of the Pali canon.[5] Out of the composers of the Sangam literature 154 were women.[6] However, the education and society of the era continued to be dominated by educated male population.[7] .

Early Common Era—High Middle Ages

Chinese scholars such as Xuanzang and Yi Jing arrived in Indian institutions of learning to survey Buddhist texts.[8] Yi Jing additionally noted the arrival of 56 scholars from India, Japan, and Korea.[9] However, the Buddhist institutions of learning were slowly giving way to a resurgent tradition of Brahmanism during that era.[9] Scholars from India also journeyed to China to translate Buddhist texts.[10] During the 10th century a monk named Dharmadeva from Nalanda journeyed to China and translated a number of texts.[10] Another centre at Vikramshila maintained close relations with Tibet.[10] The Buddhist teacher Atisa was the head monk in Vikramshila before his journey to Tibet.[10]

Examples of royal patronage include construction of buildings under the Rastrakuta dynasty in 945 CE.[11] The institutions arranged for multiple residences for educators as well as state sponsored education and arrangements for students and scholars.[11] Similar arrangements were made by the Chola dynasty in 1024 CE, which provided state support to selected students in educational establishments.[12] Temple schools from 12–13th centuries included the school at the Nataraja temple situated at Chidambaram which employed 20 librarians, out of whom 8 were copiers of manuscripts and 2 were employed for verification of the copied manuscripts.[13] The remaining staff conducted other duties, including preservation and maintained of reference material.[13]

Another establishment during this period is the Uddandapura institute established during the 8th century under the patronage of the Pala dynasty.[14] The institution developed ties with Tibet and became a centre of Tantric Buddhism.[14] During the 10–11th centuries the number of monks reached a thousand, equaling the strength of monks at the sacred Mahabodhi complex.[14] By the time of the arrival of the Islamic scholar Al Biruni India already had an established system of science and technology in place.[15] Also by the 12th century, invasions from India's northern borders disrupted traditional education systems as foreign armies raided educational institutes, among other establishments.[14]

Late Middle Ages—Early Modern Era

With the advent of Islam in India the traditional methods of education increasingly came under Islamic influence.[16] Pre-Mughal rulers such as Qutb-ud-din Aybak and other Muslim rulers initiated institutions which imparted religious knowledge.[16] Scholars such as Nizamuddin Auliya and Moinuddin Chishti became prominent educators and established Islamic monasteries.[16] Students from Bukhara and Afghanistan visited India to study humanities and science.[16]

Islamic institution of education in India included traditional madrassas and maktabs which taught grammar, philosophy, mathematics, and law influenced by the Greek traditions inherited by Persia and the Middle East before Islam spread from these regions into India.[17] A feature of this traditional Islamic education was its emphasis on the connection between science and humanities.[17] Among the centres of education in India was 18th century Delhi was the Madrasa Rahimiya under the supervision of Shah Waliullah, an educator who favored an approach balancing the Islamic scriptures and science.[18] The course at the Madrasa Rahimiya prescribed 2 books on grammar, 1 book on philosophy, 2 books on logic, 2 books on astronomy and mathematics, and 5 books on mysticism.[18] Another centre of prominence arose in Lucknow under Mulla Nizamuddin Sahlawi, who educated at the Firangi Mahal and prescribed a course called the Dars-i-Nizami which combined traditional studies with modern and laid emphasis on logic.[18]

The education system under the rule of Akbar adopted an inclusive approach with the monarch favoring additional courses: medicine, agriculture, geography, and texts from other languages and religions, such as Patanjali's work in Sanskrit.[19] The traditional science in this period was influenced by the ideas of Aristotle, Bhāskara II, Charaka and Ibn Sina.[20] This inclusive approach was not uncommon in Mughal India.[18] The more conservative monarch Aurangzeb also favored teaching of subjects which could be applied to administration.[18] The Mughals, in fact, adopted a liberal approach to sciences and as contact with Persia increased the more intolerant Ottoman school of manqul education came to be gradually substituted by the more relaxed maqul school.[21]

The Middle Ages also saw the rise of private tuition in India as state failed to invest in public education system.[20] A tutor, or Riyazi, was an educated professional who could earn a suitable living by performing tasks such as creating calendars or generating revenue estimates for nobility.[20] Another trend in this era is the mobility among professions, exemplified by Qaim Khan, a prince famous for his mastery in crafting leather shoes and forging cannons.[20]

Colonial Era

| England | Madras presidency | |

|---|---|---|

| population | 95,43,610 (1811) | 1,28,50,941 (1823) |

| No of student attening schools | 75,000 (approx) | 1,57,195 |

Before the introduction of British education, Indigenous Education was given higher importance from early time to colonial era.

In every Indian village which has retained anything of its form.the rudiments of knowledge are sought to be imparted, there is not a child, except those of the outcasts (who form no part of the community), who is not able to read, to write, to cipher; in the last branch of learning, they are confessedly most proficient.— Ludlow, British India,1858

According to a survey done in the region of Madras, There were 11,758 schools and 740 centers for higher education in Madras Presidency. The number of students was 1,88,650.[24].Around 1830 there exist 1,00,000 village schools in Bengal and Bihar region alone.[25][26]. After the introduction of British education, the numbers of these indigenous education institutes decreased drastically.[27][28].according to Minute of dissent, British government restricted indigenous education.

Efforts were then made by the Government to confine higher education and secondary education leading to higher education to boys in affluent, circumstances This again was done not in the interests of sound education but for political reasons. Rules were made calculated to restrict the diffusion of education generally and among the poorer boys in particular. Conditions for recognition for ‘ grants ’—stiff and various—-were laid down and enforced, and the non-fulfilment of any one of these conditions was liable to be followed by serious consequences. Fees were raised to a degree which considering the circumstances of the classes that resort to schools, were abnormal. When it was objected that the minimum fee would be a great hardship to poor students the answer was—-such students had no business to receive that kind of education.Managers of private schools who remitted fees in whole or in part were penalized by reduced grants-in-aid. These rules had undoubtedly the effect of checking the great expansion of education that would have taken place. This is the real explanation of the very unsatisfactory character of the nature and progress of secondary education and it will never be remedied till we are prepared either to give education to the boys ourselves or to make sufficient grants to the private schools to enable them to be staffed with competent teachers. We are at present not prepared to do either.English education, according to this policy, is to be confined to the well-to-do classes.They, it was believed, would give no trouble to Government.For this purpose, the old system of education under which a pupil could prosecute his studies from the lowest to the highest class was altered.— Sir Sankaran Nair, Minutes of Dissent

The Jesuits introduced India to both the European college system and the printing of books, through founding Saint Paul's College, Goa in 1542. The French traveler François Pyrard de Laval, who visited Goa c.1608, described the College of St Paul, praising the variety of the subjects taught there free of charge. Like many other European travelers who visited the College, he recorded that at this time it had 3000 students, from all the missions of Asia.[5] Its Library was one of the biggest in Asia, and the first Printing Press was mounted there.

The British made education, in English—a high priority hoping it would speed modernization and reduce the administrative charges.[30] The colonial authorities had a sharp debate over policy. This was divided into two schools - the orientalists, who believed that education should happen in Indian languages (of which they favoured classical or court languages like Sanskrit or Persian) or utilitarians (also called anglicists) like Thomas Babington Macaulay, who strongly believed that traditional India had nothing to teach regarding modern skills; the best education for them would happen in English. Macaulay introduced English education in India, especially through his famous minute of February 1835. He called for an educational system that would create a class of anglicised Indians who would serve as cultural intermediaries between the British and the Indians.[31] Macaulay succeeded in implementing ideas previously put forward by Lord William Bentinck, the governor general since 1829. Bentinck favoured the replacement of Persian by English as the official language, the use of English as the medium of instruction, and the training of English-speaking Indians as teachers. He was inspired by utilitarian ideas and called for "useful learning." However, Bentinck's ideas were rejected by the Court of Directors of the East India Company and he retired as governor general.[32][33]

Frykenberg examines the 1784 to 1854 period to argue that education helped integrate the diverse elements Indian society, thereby creating a new common bond from among conflicting loyalties. The native elite demanded modern education. The University of Madras, founded in 1857, became the single most important recruiting ground for generations of ever more highly trained officials. This exclusive and select leadership was almost entirely "clean-caste" and mainly Brahman. It held sway in both the imperial administration and within princely governments to the south. The position of this mandarin class was never seriously challenged until well into the twentieth century.[34]

Ellis argues that historians of Indian education have generally confined their arguments to very narrow themes linked to colonial dominance and education as a means of control, resistance, and dialogue. Ellis emphasizes the need to evaluate the education actually experienced by most Indian children, which was outside the classroom.[35] Public education expenditures varied dramatically across regions with the western and southern provinces spending three to four times as much as the eastern provinces. The reason involved historical differences in land taxes. However the rates of attendance and literacy were not nearly as skewed.[36]

Villages

Prior to the British era, education in India commenced under the supervision of a guru in traditional schools called gurukuls. The gurukuls were supported by public donation and were one of the earliest forms of public school offices. However these Gurukuls catered only to the Upper castes of the Indian society and the overwhelming masses were denied any formal education. In the colonial era, the gurukul system began to decline as the system promoted by the British began to gradually take over. Between 1881–82 and 1946–47, the number of English primary schools grew from 82,916 to 134,866 and the number of students in English Schools grew from 2,061,541 to 10,525,943. Literacy rates in accordance to British in India rose from 3.2 per cent in 1881 to 7.2 per cent in 1931 and 12.2 per cent in 1947.

Bihar and Bengal Villages

Jha argues that local schools for pre-adolescent children were in a flourishing state in thousands of villages of Bihar and Bengal until the early decades of the nineteenth century. They were village institutions, maintained by village elders with local funds, where their children (from all caste clusters and communities) could, if the father wished, receive useful skills. However, the British policies in respect of education and land control adversely affected both the village structure and the village institutions of secular education. The British legal system and the rise of caste consciousness since the second half of the nineteenth century made it worse. Gradually, village as the base of secular identity and solidarity became too weak to create and maintain its own institution by the end of the nineteenth century and the traditional system decayed.[37]

British education became solidified into India as missionary schools were established during the 1820s.[38] New policies in 1835 gave rise to the use of English as the language of instruction for advanced topics.[38]

Universities

India established a dense educational network (very largely for males) with a Western curriculum based on instruction in English. To further advance their careers many ambitious upper class men with money, including Gandhi, Nehru and Muhammad Ali Jinnah went to England, especially to obtain a legal education at the Inns of Court. By 1890 some 60,000 Indians had matriculated, chiefly in the liberal arts or law. About a third entered public administration, and another third became lawyers. The result was a very well educated professional state bureaucracy. By 1887 of 21,000 mid-level civil service appointments, 45% were held by Hindus, 7% by Muslims, 19% by Eurasians (European father and Indian mother), and 29% by Europeans. Of the 1000 top -level positions, almost all were held by Britons, typically with an Oxbridge degree.[39]

The Raj, often working with local philanthropists, opened 186 colleges and universities. Starting with 600 students scattered across 4 universities and 67 colleges in 1882, the system expanded rapidly. More exactly, there never was a "system" under the Raj, as each state acted independently and funded schools for Indians from mostly private sources. By 1901 there were 5 universities and 145 colleges, with 18,000 students (almost all male). The curriculum was Western. By 1922 most schools were under the control of elected provincial authorities, with little role for the national government. In 1922 there were 14 universities and 167 colleges, with 46,000 students.In 1947 21 universities and 496 colleges were in operation. Universities at first did no teaching or research; they only conducted examinations and gave out degrees.[40][41]

The Madras Medical College opened in 1835, and admitted women so that they could treat the female population who traditionally shied away from medical treatments under qualified male professionals.[42] The concept of educated women among medical professionals gained popularity during the late 19th century and by 1894, the Women's Christian Medical College, an exclusive medical school for women, was established in Ludhiana in Punjab.[42]

The British established the Government College University in Lahore, of present-day Pakistan in 1864. The institution was initially affiliated with the University of Calcutta for examination. The prestigious University of the Punjab, also in Lahore, was the fourth university established by the colonials in South Asia, in the year 1882.

Muhammadan Anglo-Oriental College, founded in 1875, was the first modern institution of higher education for Muslims in India. By 1920 it became The Aligarh Muslim University and was the leading intellectual center of Muslim political activity.[43] The original goals were to train Muslims for British service and prepare an elite that would attend universities in Britain. After 1920 it became a centre of political activism. Before 1939, the faculty and students supported an all-India nationalist movement. However, when the Second World War began political sentiment shifted toward demands for a Muslim separatist movement. The intellectual support it provided proved significant in the success of Jinnah and the Muslim League.[44]

Engineering

The East India Company in 1806 set up Haileybury College in England to train administrators. In India, there were four colleges of civil engineering; the first was Thomason College(Now IIT Roorkee), founded in 1847. The second was Bengal Engineering College (now Bengal Engineering and Science University, Shibpur). Their role was to provide civil engineers for the Indian Public Works Department. Both in Britain and in India, the administration and management of science, technical and engineering education was undertaken by officers from the Royal Engineers and the Indian Army equivalent, (commonly referred to as sapper officers). This trend in civil/military relationships continued with the establishment of the Royal Indian Engineering College (also known as Cooper's Hill College) in 1870, specifically to train civil engineers in England for duties with the Indian Public Works Department. he Indian Public Works Department, although technically a civilian organisation, relied on military engineers until 1947 and after.[45]

Growing awareness for the need of technical education in India gave rise to establishment of institutions such as the Indian Institute of Science, established by philanthropist Jamshetji Tata in 1909.[46] By the 1930s India had 10 institutions offering engineering courses.[47] However, with the advent of the Second World War in 1939 the "War Technicians Training Scheme" under Ernest Bevin was initiated, thereby laying the foundation of modern technical education in India.[47] Later, planned development of scientific education under Ardeshir Dalal was initiated in 1944.[47]

Science

During the 19th and 20th centuries most of the Indian princely states fell under the British Raj.[48] The British rule during the 19th century did not take adequate measures to help develop science and technology in India and instead focused more on arts and humanities.[49] Till 1899 only the University of Bombay offered a separate degree in sciences.[50] In 1899 B.Sc and M.Sc. courses were also supported by the University of Calcutta.[51] By the late 19th century India had lagged behind in science and technology and related education.[49] However, the nobility and aristocracy in India largely continued to encourage the development of sciences and technical education, both traditional and western.[48]

While some science related subjects were not allowed in the government curriculum in the 1850s the private institutions could also not follow science courses due to lack of funds required to establish laboratories etc.[51] The fees for scientific education under the British rule were also high.[51] The salary that one would get in the colonial administration was meager and made the prospect of attaining higher education bleak since the native population was not employed for high positions in the colonial setup.[51] Even the natives who did manage to attain higher education faced issues of discrimination in terms of wages and privileges.[52]

One argument for the British detachment towards the study of science in India is that England itself was gradually outpaced in science and technology by European rival Germany and a fast-growing United States so the prospects of the British Raj adopting a world class science policy towards its colonies increasingly decreased.[53] However, Deepak Kumar notes the British turn to professional education during the 1860s and the French initiatives at raising awareness on science and technology in French colonies.[53]

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Prabhu, 24

- 1 2 3 Prabhu, 25

- 1 2 Blackwell, 88

- ↑ Blackwell, 90

- 1 2 3 Raman, 236

- ↑ Raman, 237

- ↑ Raman, 236–237

- ↑ Scharfe, 144–145

- 1 2 Scharfe, 145

- 1 2 3 4 Scharfe, 161

- 1 2 Scharfe, 180

- ↑ Scharfe, 180–181

- 1 2 Scharfe, 183–184

- 1 2 3 4 Sen (1988), 12

- ↑ Blackwell, 88–89

- 1 2 3 4 Sen (1988), 22

- 1 2 Kumar (2003), 678

- 1 2 3 4 5 Kumar (2003), 679

- ↑ Kumar (2003), 678–679

- 1 2 3 4 Kumar (2003), 680

- ↑ Kumar (2003), 678-680

- ↑ Beautiful tree, p.70 ISBN 978-1939709127

- ↑ Beautiful tree, p.356 ISBN 978-1939709127

- ↑ Beautiful tree, p.250 ISBN 978-1939709127

- ↑ Adam's Reports on Vernacular Education in Bengal and Behar

- ↑ Beautiful tree, p.18 ISBN 978-1939709127

- ↑ Historical Sociology in India By Hetukar Jha ISBN 978-1138931275

- ↑ Beautiful tree ISBN 978-1939709127

- ↑ Sir Sankaran Nair's Minutes of Dissent, ISBN 978-1293563090

- ↑ Catriona Ellis, "Education for All: Reassessing the Historiography of Education in Colonial India." History Compass (2009) 7#2 pp 363-375

- ↑ Stephen Evans, "Macaulay's minute revisited: Colonial language policy in nineteenth-century India," Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development (2002) 23#4 pp 260-281 doi:10.1080/01434630208666469

- ↑ Suresh Chandra Ghosh, "Bentinck, Macaulay and the introduction of English education in India," History of Education, (March 1995) 24#1 pp 17-24

- ↑ Percival Spear, "Bentinck and Education," Cambridge Historical Journal (1938) 6#1 pp. 78-101 in JSTOR

- ↑ Robert Eric Frykenberg, "Modern Education in South India, 1784-1854: Its Roots and Its Role as a Vehicle of Integration under Company Raj," American Historical Review, (Feb 1986), 91#1 pp 37-67 in JSTOR

- ↑ Catriona Ellis, "Education for All: Reassessing the Historiography of Education in Colonial India," History Compass, (March 2009) 7#2 pp 363-375

- ↑ Latika Chaudhary, "Land revenues, schools and literacy: A historical examination of public and private funding of education," Indian Economic and Social History Review, (Apr-June 2010), 47#2 pp 179-204

- ↑ Hetukar Jha, "Decay of Village Community and the Decline of Vernacular Education in Bihar and Bengal in the Colonial Era," Indian Historical Review, (June 2011), 38#1 pp 119-137

- 1 2 Blackwell, 92

- ↑ Robin J. Moore, "Imperial India, 1858-1914," in Roy Porter, ed. Oxford History of the British Empire: The Nineteenth Century (2001), p 431

- ↑ C. M. Ramachandran, Problems of higher education in India: a case study (1987) p 71-7

- ↑ Zareer Masani, Indian Tales of the Raj (1988) p. 89

- 1 2 Arnold, 88

- ↑ Gail Minault and David Lelyveld, "The Campaign for a Muslim University 1898-1920," Modern Asian Studies, (March 1974) 8#2 pp 145-189

- ↑ Mushirul Hasan, "Nationalist and Separatist Trends in Aligarh, 1915-47," Indian Economic and Social History Review, (Jan 1985), Vol. 22 Issue 1, pp 1-33

- ↑ John Black, "The military influence on engineering education in Britain and India, 1848-1906," Indian Economic and Social History Review, (Apr-June 2009), 46#2 pp 211-239

- ↑ Sen (1989), 227

- 1 2 3 Sen (1989), 229

- 1 2 Arnold, 8

- 1 2 Kumar (1984), 253-254

- ↑ Kumar (1984), 254

- 1 2 3 4 Kumar (1984), 255

- ↑ Kumar (1984), 255-256

- 1 2 Kumar (1984), 258

References

- Arnold, David (2004), The New Cambridge History of India: Science, Technology and Medicine in Colonial India, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-56319-4.

- Blackwell, Fritz (2004), India: A Global Studies Handbook, ABC-CLIO, Inc., ISBN 1-57607-348-3.

- Ellis, Catriona. (2009) "Education for All: Reassessing the Historiography of Education in Colonial India," History Compass, (March 2009), 7#2 pp 363–375,

- Jayapalan N. (2005) History Of Education In India excerpt and text search

- Kumar, Deepak (2003), "India", The Cambridge History of Science vol 4: Eighteenth-Century Science edited by Roy Porter, pp. 669–687, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-57243-6.

- Kumar, Deepak (1984), "Science in Higher Education: A Study in Victorian India", Indian Journal of History of Science, 19#3 pp: 253-260, Indian National Science Academy.

- Prabhu, Joseph (2006), "Educational Institutions and Philosophies, Traditional and Modern", Encyclopedia of India (vol. 2) edited by Stanley Wolpert, pp. 23–28, Thomson Gale, ISBN 0-684-31351-0.

- Raman, S.A. (2006), "Women's Education", Encyclopedia of India (vol. 4) edited by Stanley Wolpert, pp. 235–239, Thomson Gale, ISBN 0-684-31353-7.

- Scharfe, Hartmut (2002), Education in Ancient India, (Brill Academic Publishers, ISBN 978-90-04-12556-8)

- Sen, Bimal (1989), "Development of Technical Education in India and State Policy-A Historical Perspective", Indian Journal of History of Science, 24#2 pp: 224-248, Indian National Science Academy.

- Sen, S.N. (1988), "Education in Ancient and Medieval India", Indian Journal of History of Science, 23#1 pp: 1-32, Indian National Science Academy.

- Sharma, Ram Nath. (1996) History of education in India excerpt and text search