History of Maharashtra

The history of Maharashtra can be traced to approximately the 4th century BCE. From the 4th century BCE until 875, Maharashtri Prakrit and its Apabhraṃśas were the dominant languages of the region. Marathi, which evolved from Maharashtri Prakrit, has been the lingua franca from the 9th century onwards. The oldest stone inscriptions in Marathi language can be seen at Shravana Belgola in modern-day Karnataka at the foot of the Bahubali Statue. In the course of time, the term Maharashtra was used to describe a region which consisted of Aparanta, Vidarbha, Mulak, Ashmak Assaka and Kuntal. Tribal communities of Naga, Munda and Bhil peoples inhabited this area, also known as Dandakaranya, in ancient times. The name Maharashtra is believed to be originated from rathi, which means "chariot driver". Maharashtra entered the recorded history in the 2nd century BC, with the construction of its first Buddhist caves. The name Maharashtra first appeared in the 7th century in the account of a contemporary Chinese traveler, Huan Tsang. According to the recorded History, the first Hindu King ruled the state during the 6th century, based in Badami.

Maharashtra during 4th century BC-12th century AD

The region that is present day Maharashtra was part of a number of empires in the first millennium. These include the Maurya empire, Satavahana dynasty, the Vakataka dynasty, the Chalukya dynasty and the Rashtrakuta dynasty. And Most of these empires extended over a large swathes of Indian territory. Some of the greatest monuments in Maharashtra such as the Ajantha and Ellora Caves were built during the time of these empires. Maharashtra was ruled by the Maurya Empire in the 4th and 3rd century BCE. Around 230 BCE Maharashtra came under the rule of the Satavahana dynasty which ruled the region for 400 years.[1] The greatest ruler of the Satavahana Dynasty was Gautamiputra Satakarni who defeated the Scythian invaders. The Vakataka dynasty ruled from c. 250–470 CE. The Satavahana dynasty used Prakrit (not referred to as Maharashtri then, Telugu or other Dravidian languages were not used by Satavahanas) while the Vakataka dynasty patronized Prakrit and Sanskrit.

Pravarapura-Nandivardhana branch:The Pravarapura-Nandivardhana branch ruled from various sites like Pravarapura (Paunar) in Wardha district and Mansar and Nandivardhan (Nagardhan) in Nagpur district. This branch maintained matrimonial relations with the Imperial Guptas Vatsagulma branch:The Vatsagulma branch was founded by Sarvasena, the second son of Pravarasena I after his death. King Sarvasena made Vatsagulma, the present day Washim in Washim district of Maharashtra his capital.[6] The territory ruled by this branch was between the Sahydri Range and the Godavari River. They patronized some of the Buddhist caves at Ajanta. Prabhavatigupta was queen and regent of the Vākāṭaka Empire. Her father was Chandragupta II of the Gupta Empire and her mother was Kuberanaga, of the Naga. She married Rudrasena II of the Vākāṭaka. After his death in 385, she ruled as regent for her two young sons, Divakarasena and Damodarasena, for twenty years

The Chalukya dynasty ruled Maharashtra from the 6th century to the 8th century and the two prominent rulers were Pulakeshin II, who defeated the north Indian Emperor Harsha and Vikramaditya II, who defeated the Arab invaders in the 8th century. The Rashtrakuta Dynasty ruled Maharashtra from the 8th to the 10th century.[2] The Arab traveler Sulaiman called the ruler of the Rashtrakuta Dynasty (Amoghavarsha) as "one of the 4 great kings of the world".[3] The Chalukya dynasty and Rashtrakuta Dynasty had their capitals in modern-day Karnataka and they used Kannada and Sanskrit as court languages. From the early 11th century to the 12th century the Deccan Plateau was dominated by the Western Chalukya Empire and the Chola dynasty.[4] Several battles were fought between the Western Chalukya Empire and the Chola dynasty in the Deccan Plateau during the reigns of Raja Raja Chola I, Rajendra Chola I, Jayasimha II, Someshvara I and Vikramaditya VI.[5]

Seuna dynasty 12th-14th century

The Yadavas of Devagiri Dynasty was an Indian dynasty, which at its peak ruled a kingdom stretching from the Tungabhadra to the Narmada rivers, including present-day Maharashtra, north Karnataka and parts of Madhya Pradesh, from its capital at Devagiri (present-day Daulatabad in modern Maharashtra). The Yadavas initially ruled as feudatories of the Western Chalukyas.[6] The founder of the Suena dynasty was Dridhaprahara, the son of Subahu. According to Vratakhanda, his capital was Shrinagara. However, an early inscription suggests that Chandradityapura (modern Chandwad in the Nasik district) was the capital.[7] The name Seuna comes from Dridhaprahara's son, Seunachandra, who originally ruled a region called Seunadesha (present-day Khandesh). Bhillama II, a later ruler in the dynasty, assisted Tailapa II in his war with the Paramara king Munja. Seunachandra II helped Vikramaditya VI in gaining his throne. Around the middle of the 12th century, as the Chalukya power waned, they declared independence and established rule that reached its peak under Singhana II. The Yadavas of Devagiri patronised Marathi[8] which was their court language.[9][10] Kannada may also have been a court language during Seunachandra's rule, but Marathi was the only court-language of Ramchandra and Mahadeva Yadavas. The Yadava capital Devagiri became a magnet for learned scholars in Marathi to showcase and find patronage for their skills. The origin and growth of Marathi literature is directly linked with rise of Yadava dynasty.[11]

According to scholars such as Prof. George Moraes,[12] V. K. Rajwade, C. V. Vaidya, Dr. A.S. Altekar, Dr. D.R. Bhandarkar, and J. Duncan M. Derrett,[13] the Seuna rulers were of Maratha descent who patronized the Marathi language.[8] Digambar Balkrishna Mokashi noted that the Yadava dynasty was "what seems to be the first true Maratha empire".[14] In his book Medieval India, C.V. Vaidya states that Yadavas are "definitely pure Maratha Kshatriyas".

Islamic Rule

In the early 14th century, the Yadava dynasty, which ruled most of present-day Maharashtra, was overthrown by the Delhi Sultanate ruler Ala-ud-din Khalji. Later, Muhammad bin Tughluq conquered parts of the Deccan, and temporarily shifted his capital from Delhi to Daulatabad in Maharashtra. After the collapse of the Tughluqs in 1347, the local Bahmani Sultanate of Gulbarga took over, governing the region for the next 150 years.[15] After the break-up of the Bahamani sultanate in 1518, the Maharashtra region was split ibetween five Deccan Sultanates: Nizamshah of Ahmednagar, Adilshah of Bijapur, Qutubshah of Golkonda, Bidarshah of Bidar and Imadshah of Elichpur.[16] These kingdoms often fought with each other. United, they decisively defeated the Vijayanagara Empire of the south in 1565.[17] The present area of Mumbai was ruled by the Sultanate of Gujarat before its capture by Portugal in 1535 and the Faruqi dynasty ruled the Khandesh region between 1382 and 1601 before finally getting annexed by the Mughal Empire. Malik Ambar, the regent of the Nizamshahi dynasty of Ahmednagar from 1607 to 1626[18] increased the strength and power of Murtaza Nizam Shah and raised a large army. Malik Ambar was a proponent of guerilla warfare in the Deccan region. Malik Ambar assisted Mughal prince Khurram (who later became emperor Shah Jahan) in his struggle against his stepmother, Nur Jahan, who had ambitions of getting the Delhi throne for her son-in-law.[19] The Deccan kingdoms were eventually swallowed by the Mughal Empire or by the emerging Maratha forces in the second half of the 17th Century.

The early period of Islamic rule saw atrocities such as imposition of Jaziya tax on non-Muslims, temple demolition and forcible conversions. However, the mainly Hindu population and the Islamic rulers over time came to an accommodation. For most of this period Brahmins were in charge of accounts whereas revenue collection was in the hands of Marathas who had watans (Hereditary rights) of Patilki ( revenue collection at village level) and Deshmukhi ( revenue collection over a larger area). A number of families such as Bhosale, Shirke, Ghorpade, Jadhav, More, Mahadik, and Ghatge loyally served different sultans at different periods in time. All watandars considered their watan a source of economic power and pride and were reluctant to part with it. The Watandars were the first to oppose Shivaji because that hurt their economic interests.[16] Since most of the population was Hindu and spoke Marathi, even the sultans such as Ibrahim Adil Shah I adopted Marathi as the court language, for administration and record keeping..,[16][20][21]

Maratha Empire

The Marathas dominated the political scene in India from the middle of the 17th century to the early 19th century as the Maratha Empire. The term Maratha here is used in a comprehensive sense to include all Marathi-speaking people rather than the distinct community with the same name to which Shivaji, the founder of the maratha empire belonged.

Chhatrapti Shivaji

Chhatrapati Shivaji is considered the founder of the modern Marathi nation; his policies were instrumental in forging a distinct Maharashtrian identity. Shivaji Bhonsle c. 1627/1630[22] – 3 April 1680), also known as Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj, was a member of the Bhonsle clan. Shivaji carved out an enclave from the declining Adilshahi sultanate of Bijapur that formed the genesis of the Maratha Empire. In 1674, he was formally crowned as the Chhatrapati (Monarch) of his realm at Raigad. Shivaji was an able warrior and established a government that included such modern concepts as a cabinet (ashtapradhana mandala), foreign affairs (dabir) and internal intelligence. Shivaji established an effective civil and military administration. He also built a powerful navy and erected new forts like Sindhudurg and strengthened old ones like Vijayadurg on the west coast of Maharashtra.

Expansion of Maratha Influence in 18th Century under Shahu I and Peshwa rule

The death of Aurangzeb in 1707 after an exhausting 27 years of war against the Marathas led to the swift decline of the Mughal Empire. \During much of this era, the Peshwas, belonging to the (Bhat) Deshmukh Marathi Chitpavan Brahmin family, controlled the Maratha army and later became the hereditary heads of the Maratha Empire from 1749 to 1818.[23] During their rein, the Maratha empire reached its zenith in 1760, ruling most of the Indian subcontinent.[24]Bajirao I, the second Peshwa from the Bhat family was only 20 when given the position. For his campaigns in North India, he actively promoted young leaders of his own age such as Ranoji Shinde, Malharrao Holkar, the Puar brothers and Pilaji Gaekwad. These leaders also did not come from the traditional aristocratic families of Maharashtra[25] Separate from Bajirao I, Raghoji Bhonsle expanded Maratha rule in central and East India.[26] All these military leaders or their descendants later became rulers in their own right during the Maratha Confederacy era.

One of the tools of the empire was collection of Chauth or 25% of the revenue from states that submitted to Maratha power. The Marathas also had an elaborate land revenue system which was retained by the British East India company when they gained control of Maratha territory[27]

The areas controlled by the Peshwa were annexed by the East India Company in 1818.

The Maratha Navy

The Marathas also developed a potent Navy circa 1660s, which at its peak, dominated the territorial waters of the western coast of India from Mumbai to Savantwadi.[28] It would engage in attacking the British, Portuguese, Dutch, and Siddi Naval ships and kept a check on their naval ambitions. The Maratha Navy dominated till around the 1730s, was in a state of decline by 1770s, and ceased to exist by 1818.[29]

Maharashtra under British rule and The Freedom Movement

The British East India Company slowly expanded areas under its rule during the 18th century. Their conquests of Maharashtra was completed in 1818 with the defeat of Peshwa Bajirao II in the Third Anglo-Maratha War [30]

Bal Gangadhar Tilak played a major role in the Indian independence movement. He was widely recognised as a leader of national importance & a man of method. Being a person with an extremist attitude, he was instrumental in encouraging the Indian masses in participating in the freedom struggle.

A popular quotation attributed to Tilak is:

Swaraj (self-rule) is my birthright

And I will achieve it!

Barrister Dr. B. R. Ambedkar, the first Law Minister of India, championed the cause of Depressed Classes of India, the lower caste population who were oppressed for centuries. Ambedkar disagreed with mainstream leaders like Gandhi on issues including untouchability, government system and the partition of India. This did not prevent him from struggling for the rights of his brethren among the lower castes of the country. His leadership of dalit or Depressed Classes led to the Dalit movement that still endures. Ambedkar most importantly played the pivotal role in writing the constitution of India and hence he is considered as the father of the Indian Constitution.

The ultimatum in 1942 to the British to "Quit India" was given in Mumbai, and culminated in the transfer of power and the independence of India in 1947. Raosaheb and Achutrao Patwardhan, Nanasaheb Gore, Shreedhar Mahadev Joshi, Yeshwantrao Chavan, Swami Ramanand Bharti, Nana Patil, Dhulappa Navale, V.S. Page, Vasant Patil, Dhondiram Mali, Aruna Asif Ali, Ashfaqulla Khan and several others leaders from Maharashtra played a prominent role in this struggle. BG Kher was the first Chief Minister of the tri-lingual Bombay Presidency in 1937.

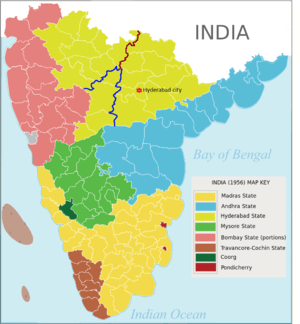

The States Reorganisation Act, 1956

Marathi majority taluks transferred to Adilabad, Medak, Nizamabad and Mahaboobnagar districts of new Telugu State (now Telangana) and Karnataka in 1956. Even today, the old town names of all these regions are Marathi names.

Transferred to Telangana (1) Alampur and Gadwal taluks of Raichur district and Kodangal taluk of Gulbarga district; (2) Tandur taluk of Gulbarga district; (3) Zahirabad taluk (except Nirna circle), Nyalkal circle of Bidar taluk and Narayankhed taluk of Bidar district; (4) Bichkonda and Jukkal circles of Deglur taluk of Nanded district;

Transferred to Karnataka (1) Belgaum District (2) Bijapur District (3) Gulbarga District (4) Bidar District [31]

References

Citations

- ↑ India Today: An Encyclopedia of Life in the Republic: p.440

- ↑ Indian History - page B-57

- ↑ A Comprehensive History Of Ancient India (3 Vol. Set): p.203

- ↑ The Penguin History of Early India: From the Origins to AD 1300 by Romila Thapar: p.365-366

- ↑ Ancient Indian History and Civilization by Sailendra Nath Sen: p.383-384

- ↑ Keay, John (2001-05-01). India: A History. Atlantic Monthly Pr. pp. 252–257. ISBN 0-8021-3797-0. The quoted pages can be read at Google Book Search.

- ↑ "Nasik District Gazetteer: History – Ancient period". Archived from the original on 2006-11-07. Retrieved 2006-10-01.

- 1 2 Kulkarni, Chidambara Martanda (1966). Ancient Indian History & Culture. Karnatak Pub. House. p. 233.

- ↑ "India 2000 – States and Union Territories of India" (PDF). Indianembassy.org. Retrieved 2016-02-27.

- ↑ "Yadav – Pahila Marathi Bana" S.P. Dixit (1962)

- ↑ https://web.archive.org/web/20070121015805/http://www.bhashaindia.com/Patrons/LanguageTech/Marathi.aspx. Archived from the original on 21 January 2007. Retrieved 3 January 2007. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Professor George Moraes. "Pre-Portuguese Culture of Goa". International Goan Convention. Archived from the original on 2006-10-15. Retrieved 2006-10-01.

- ↑ Murthy, A. V. Narasimha (1971). The Sevunas of Devagiri. Rao and Raghavan. p. 32.

- ↑ Mokashi, Digambar Balkrishna (1987-07-01). Palkhi: An Indian Pilgrimage. SUNY Press. p. 37. ISBN 0-88706-461-2.

- ↑ "Kingdoms of South Asia – Indian Bahamani Sultanate". The History Files, United Kingdom. Retrieved 12 September 2014.

- 1 2 3 Kulkarni, G.T. (1992). "DECCAN (MAHARASHTRA) UNDER THE MUSLIM RULERS FROM KHALJIS TO SHIVAJI : A STUDY IN INTERACTION, PROFESSOR S.M KATRE Felicitation". Bulletin of the Deccan College Research Institute. 51/52,: 501–510. JSTOR 42930434.

- ↑ Bhasker Anand Saletore (1934). Social and Political Life in the Vijayanagara Empire (A.D. 1346-A.D. 1646). B.G. Paul.

- ↑ A Sketch of the Dynasties of Southern India. E. Keys. 1883. pp. 26–28.

- ↑ "Malik Ambar (1548–1626): the rise and fall of military slavery". British Library. Retrieved 12 September 2014.

- ↑ Gordon, Stewart (1993). Cambridge History of India: The Marathas 1600-1818. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University press. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-521-26883-7.

- ↑ Kamat, Jyotsna. "The Adil Shahi Kingdom (1510 CE to 1686 CE)". Kamat's Potpourri. Retrieved 4 December 2014.

- ↑ Indu Ramchandani, ed. (2000). Student’s Britannica: India (Set of 7 Vols.) 39. Popular Prakashan. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-85229-760-5.

- ↑ Shirgaonkar, Varsha S. "Eighteenth Century Deccan: Cultural History of the Peshwas." Aryan Books International, New Delhi (2010). ISBN 978-81-7305-391-7

- ↑ Shirgaonkar, Varsha S. "Peshwyanche Vilasi Jeevan." (Luxurious Life of Peshwas) Continental Prakashan, Pune (2012). ISBN 8174210636

- ↑ Gordon, Stewart (2008). The Marathas 1600-1818. (Digitally print. 1. pbk. version. ed.). Cambridge [u.a.]: Cambridge Univ Pr. pp. 117–121. ISBN 978-0521033169.

- ↑ "Forgotten Indian history: The brutal Maratha invasions of Bengal".

- ↑ Wink, A., 1983. Maratha revenue farming. Modern Asian Studies, 17(04), pp.591-628.

- ↑ Sridharan, K. Sea: Our Saviour. New Age International (P) Ltd. ISBN 81-224-1245-9.

- ↑ Sharma, Yogesh. Coastal Histories: Society and Ecology in Pre-modern India. Primus Books. p. 66. ISBN 978-93-80607-00-9.

- ↑ Omvedt, G.in 1973. Development of the Maharashtrian Class Structure, 1818 to 1931. Economic and Political Weekly, pp.1417-1432..

- ↑ "The States Reorganisation Act, 1956". Indiankanoon.org. Retrieved 2016-02-27.

Sources

- महाराष्ट्राचा गौरवशाली इतिहास / The History of Maharashtra.....

- James Grant Duff, History of the Mahrattas, 3 vols. London, Longmans, Rees, Orme, Brown, and Green (1826). ISBN 81-7020-956-0

- Mahadev Govind Ranade, Rise of the Maratha Power (1900); reprint (1999). ISBN 81-7117-181-8

- Richard Eaton, The new Cambridge history of India,[1]

External links

- ↑ Eaton, Richard M. (2005). The new Cambridge history of India. (1. publ. ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 154. ISBN 0-521-25484-1. Retrieved 25 March 2016.