People's Socialist Republic of Albania

| People's Socialist Republic of Albania | ||||||||||

| Republika Popullore Socialiste e Shqipërisë | ||||||||||

| Satellite state of the Soviet Union (until 1968) Member of the Warsaw Pact (until 1968) | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

| Motto Ti Shqipëri, më jep nder, më jep emrin Shqipëtar "You Albania, give me honour, give me the name Albanian" • Proletarë të të gjitha vendeve, bashkohuni! "Proletarians of all countries, unite!" | ||||||||||

| Anthem Himni i Flamurit (in Albanian) Hymn to the Flag | ||||||||||

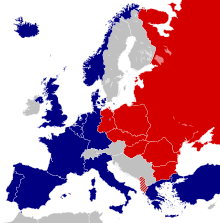

Location of Albania in Europe. | ||||||||||

| Capital | Tirana | |||||||||

| Languages | Albanian | |||||||||

| Government | Unitary Marxist-Leninist Stalinist-Hoxhaist one-party socialist republic under totalitarian dictatorship (1946–91) Unitary parliamentary republic (1991–92) | |||||||||

| First Secretary | ||||||||||

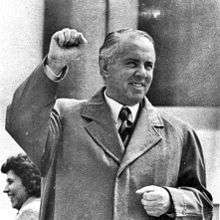

| • | 1946–1985 | Enver Hoxha | ||||||||

| • | 1985–1991 | Ramiz Alia | ||||||||

| Chairman | ||||||||||

| • | 1946–1953 | Omer Nishani | ||||||||

| • | 1953–1982 | Haxhi Lleshi | ||||||||

| • | 1982–1991 | Ramiz Alia | ||||||||

| Prime Minister | ||||||||||

| • | 1946–1954 | Enver Hoxha | ||||||||

| • | 1954–1981 | Mehmet Shehu | ||||||||

| • | 1982–1991 | Adil Çarçani | ||||||||

| Legislature | People's Assembly | |||||||||

| Historical era | Cold War | |||||||||

| • | Formation | 11 January 1946 | ||||||||

| • | Soviet-Albanian Split | 1961 | ||||||||

| • | Constitution amended | 28 December 1976 | ||||||||

| • | Sino-Albanian split | 1978 | ||||||||

| • | Fall of communism | 11 December 1990 | ||||||||

| • | Democratic elections | 31 March 1991 | ||||||||

| • | Reconstituted as the Republic of Albania | 30 April 1991 | ||||||||

| • | First parliamentary elections | 22 March 1992 | ||||||||

| • | New Albanian Constitution | 28 November 1998 | ||||||||

| Area | ||||||||||

| • | 1989 | 28,748 km2 (11,100 sq mi) | ||||||||

| Population | ||||||||||

| • | 1945 est. | 1,122,044 | ||||||||

| • | 1989 est. | 3,512,317 | ||||||||

| Density | 122/km2 (316/sq mi) | |||||||||

| Currency | Franga 1946–1947

Albanian lek 1947–1992 | |||||||||

| Calling code | +355 | |||||||||

| ||||||||||

| Today part of | | |||||||||

Albania (/ælˈbeɪniə, ɔːl-/, a(w)l-BAY-nee-ə; Albanian: Shqipëri/Shqipëria; Gheg Albanian: Shqipni/Shqipnia, Shqypni/Shqypnia[1]), officially the People's Socialist Republic of Albania (Albanian: Republika Popullore Socialiste e Shqipërisë), was a socialist state that ruled Albania from 1946 to its fall in 1992.[2] From 1946 to 1976 it was known as the People's Republic of Albania, and from 1944 to 1946 as the Democratic Government of Albania. Throughout this period the country had a reputation for its Stalinist style of state administration dominated by Enver Hoxha and the Party of Labour of Albania and for policies stressing national unity and self-reliance. Travel and visa restrictions made Albania one of the most difficult countries to visit or to travel from. In 1967, it declared itself the world's first atheist state.[3] It was the only Warsaw Pact member to formally withdraw from the alliance before 1990, an action occasioned by the Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968. The first multi-party elections in Socialist Albania took place on 31 March 1991 – the communists gained a majority in an interim government and the first parliamentary elections were held on 22 March 1992.[4] The People's Socialist Republic was officially dissolved on 28 November 1998 upon the adoption of the new Constitution of Albania.

Consolidation of power and initial reforms

On 29 November 1944, Albania was liberated by the National Liberation Movement (In Albanian: Lëvizja Nacional-Çlirimtare LNC). The Anti-Fascist National Liberation Council, formed in May, became the country's provisional government.

The government, like the LNC, was dominated by the two-year-old Communist Party of Albania, and the party's first secretary, Enver Hoxha, became Albania's prime minister. King Zog I was barred from ever returning to Albania, though the country nominally remained a monarchy. From the start, the LNC government was openly a one-party Communist regime. In the other countries in what became the Soviet bloc, the Communists were at least nominally part of coalition governments for a few years before taking complete control. Having sidelined the nationalist Balli Kombëtar after their collaboration with the Nazis, the LNC moved quickly to consolidate its power, liberate the country's tenants and workers, and join Albania fraternally with other socialist countries.

The internal affairs minister, Koçi Xoxe, "an erstwhile pro-Yugoslavia tinsmith", presided over the trial of many non-communist politicians condemned as "enemies of the people" and "war criminals".[5] Many were sentenced to death. Those spared were imprisoned for years in work camps and jails and later settled on state farms built on reclaimed marshlands.

In December 1944, the provisional government adopted laws allowing the state to regulate foreign and domestic trade, commercial enterprises, and the few industries the country possessed. The laws sanctioned confiscation of property belonging to political exiles and "enemies of the people." The state also expropriated all German- and Italian-owned property, nationalized transportation enterprises, and canceled all concessions granted by previous Albanian governments to foreign companies.

In August 1945, the provisional government adopted the first sweeping agricultural reforms in Albania's history. The country's 100 largest landowners, who controlled close to a third of Albania's arable land, had frustrated all agricultural reform proposals before the war. The communists' reforms were aimed at squeezing large landowners out of business, winning peasant support, and increasing farm output to avert famine. The government annulled outstanding agricultural debts, granted peasants access to inexpensive water for irrigation, and nationalized forest and pastureland.

Under the Agrarian Reform Law, which redistributed about half of Albania's arable land, the government confiscated property belonging to absentee landlords and people not dependent on agriculture for a living. The few peasants with agricultural machinery were permitted to keep up to 400,000 square metres (4,300,000 sq ft) of land; the landholdings of religious institutions and peasants without agricultural machinery were limited to 200,000 square metres (2,200,000 sq ft); and landless peasants and peasants with tiny landholdings were given up to 50,000 square metres (540,000 sq ft), although they had to pay nominal compensation.

In December 1945, Albanians elected a new People's Assembly, but voters were presented with a single list from the Communist-dominated Democratic Front (previously the National Liberation Movement). Official ballot tallies showed that 92% of the electorate voted and that 93% of the voters chose the Democratic Front ticket.

The assembly convened in January 1946. Its first act was to formally abolish the monarchy and to declare Albania a "people's republic." However, as mentioned above, the country had been a Communist state for just over two years. After months of angry debate, the assembly adopted a constitution that mirrored the Yugoslav and Soviet constitutions. A couple of months later, the assembly members chose a new government, which was emblematic of Hoxha's continuing consolidation of power: Hoxha became simultaneously prime minister, foreign minister, defense minister, and the army's commander in chief. Xoxe remained both internal affairs minister and the party's organizational secretary.

In late 1945 and early 1946, Xoxe and other party hard-liners purged moderates who had pressed for close contacts with the West, a modicum of political pluralism, and a delay in the introduction of strict communist economic measures until Albania's economy had more time to develop. Hoxha remained in control despite the fact that he had once advocated restoring relations with Italy and even allowing Albanians to study in Italy.

The government took major steps to introduce a Stalinist-style centrally planned economy in 1946.[6] It nationalized all industries, transformed foreign trade into a government monopoly, brought almost all domestic trade under state control, and banned land sales and transfers. Planners at the newly founded Economic Planning Commission emphasized industrial development and in 1947 the government introduced the Soviet cost-accounting system.

Albanian–Yugoslav tensions

Until Yugoslavia's expulsion from the Cominform in 1948, Albania was effectively a Yugoslav satellite. In repudiating the 1943 Albanian internal Mukaj agreement under pressure from the Yugoslavs, Albania's communists had given up on their demands for a Yugoslav cession of Kosovo to Albania after the war. In January 1945, the two governments signed a treaty establishing Kosovo as a Yugoslav autonomous province. Shortly thereafter, Yugoslavia became the first country to recognize Albania's provisional government.

In July 1946, Yugoslavia and Albania signed a treaty of friendship and cooperation that was quickly followed by a series of technical and economic agreements laying the groundwork for integrating the Albanian and Yugoslav economies. The pacts provided for coordinating the economic plans of both states, standardizing their monetary systems, and creating a common pricing system and a customs union. So close was the Yugoslav-Albanian relationship that Serbo-Croatian became a required subject in Albanian high schools.

Yugoslavia signed a similar friendship treaty with Bulgaria, and Marshal Josip Broz Tito and Bulgaria's Georgi Dimitrov talked of plans to establish a Balkan federation to include Albania, Yugoslavia, and Bulgaria. Yugoslav advisers poured into Albania's government offices and its army headquarters. Tirana was desperate for outside aid, and about 20,000 tons of Yugoslav grain helped stave off famine. Albania also received US$26.3 million from the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration immediately after the war but had to rely on Yugoslavia for investment and development aid.

Joint Albanian–Yugoslav companies were created for mining, railroad construction, the production of petroleum and electricity, and international trade. Yugoslav investments led to the construction of a sugar refinery in Korçë, a food-processing plant in Elbasan, a hemp factory at Rrogozhinë, a fish cannery in Vlorë, and a printing press, telephone exchange, and textile mill in Tirana. The Yugoslavs also bolstered the Albanian economy by paying three times the international price for Albanian copper and other materials.

Relations between Albania and Yugoslavia declined, however, when the Albanians began complaining that the Yugoslavs were paying too little for Albanian raw materials and exploiting Albania through the joint stock companies. In addition, the Albanians sought investment funds to develop light industries and an oil refinery, while the Yugoslavs wanted the Albanians to concentrate on agriculture and raw-material extraction. The head of Albania's Economic Planning Commission, and Hoxha's right-hand man,[7] Nako Spiru, became the leading critic of Yugoslavia's efforts to exert economic control over Albania. Tito distrusted the intellectuals (Hoxha and his allies) of the Albanian party and, through Xoxe and his loyalists, attempted to unseat them.

In 1947, Yugoslavia acted against anti-Yugoslav Albanian communists, including Hoxha and Spiru. In May, Tirana announced the arrest, trial, and conviction of nine People's Assembly members, all known for opposing Yugoslavia, on charges of antistate activities. A month later, the Communist Party of Yugoslavia's Central Committee accused Hoxha of following "independent" policies and turning the Albanian people against Yugoslavia. This was the closest Hoxha came from being removed from power. Apparently attempting to buy support inside the Albanian Communist Party, Belgrade extended Tirana US$40 million worth of credits, an amount equal to 58% of Albania's 1947 state budget. A year later, Yugoslavia's credits accounted for nearly half of the state budget. Relations worsened in the fall, however, when Spiru's commission developed an economic plan that stressed self-sufficiency, light industry, and agriculture. The Yugoslavs complained bitterly. Subsequently, at a November 1947 meeting of the Albanian Economic Central Committee, Spiru came under intense criticism, spearheaded by Xoxe. Failing to win support from anyone within the party (he was effectively a fall guy for Hoxha) he committed suicide the very next day.[8]

The insignificance of Albania's standing in the communist world was clearly highlighted when the emerging East European nations did not invite the Albanian party to the September 1947 founding meeting of the Cominform. Rather, Yugoslavia represented Albania at Cominform meetings. Although the Soviet Union gave Albania a pledge to build textile and sugar mills and other factories and to provide Albania agricultural and industrial machinery, Joseph Stalin told Milovan Djilas, at the time a high-ranking member of Yugoslavia's communist hierarchy, that Yugoslavia should "swallow" Albania.

The pro-Yugoslav faction wielded decisive political power in Albania well into 1948. At a party plenum in February and March, the communist leadership voted to merge the Albanian and Yugoslav economies and militaries. Hoxha even denounced Spiru for attempting to ruin Albanian-Yugoslav relations. During a party Political Bureau (Politburo) meeting a month later, Xoxe proposed appealing to Belgrade to admit Albania as a seventh Yugoslav republic. When the Cominform expelled Yugoslavia on 28 June, however, Albania made a rapid about-face in its policy toward Yugoslavia. Three days later, Tirana gave the Yugoslav advisers in Albania 48 hours to leave the country, rescinded all bilateral economic agreements with its neighbor, and launched a virulent anti-Yugoslav propaganda blitz that transformed Stalin into an Albanian national hero, Hoxha into a warrior against foreign aggression, and Tito into an imperialist monster.

Albania entered an orbit around the Soviet Union, and in September 1948 Moscow stepped in to compensate for Albania's loss of Yugoslav aid. The shift proved to be a boon for Albania because Moscow had far more to offer than hard-strapped Belgrade. The fact that the Soviet Union had no common border with Albania also appealed to the Albanian regime because it made it more difficult for Moscow to exert pressure on Tirana. In November at the First Party Congress of the Albanian Party of Labor (APL), the former Albanian Communist Party renamed at Stalin's suggestion, Hoxha pinned the blame for the country's woes on Yugoslavia and Xoxe. Hoxha had Xoxe sacked as internal affairs minister in October, replacing him with Shehu. After a secret trial in May 1949, Xoxe was executed. The subsequent anti-Titoist purges in Albania brought the liquidation of 14 members of the party's 31 person Central Committee and 32 of the 109 People's Assembly deputies. Overall, the party expelled about 25% of its membership. Yugoslavia responded with a propaganda counterattack, canceled its treaty of friendship with Albania, and in 1950 withdrew its diplomatic mission from Tirana.

Deteriorating relations with the West

Albania's relations with the West soured after the Communist regime's refusal to allow free elections in December 1945. Albania restricted the movement of United States and British personnel in the country, charging that they had instigated anti-Communist uprisings in the northern mountains. Britain announced in April that it would not send a diplomatic mission to Tirana; the United States withdrew its mission in November; and both the United States and Britain opposed admitting Albania to the United Nations (UN). The Albanian regime feared that the United States and Britain, which were supporting anti-Communist forces in the ongoing civil war in Greece, would back Greek demands for territory in southern Albania; and anxieties grew in July when a United States Senate resolution backed the Greek demands.

A major incident between Albania and Britain erupted in 1946 after Tirana claimed jurisdiction over the channel between the Albanian mainland and the Greek island of Corfu. Britain challenged Albania by sailing four destroyers into the channel. Two of the ships struck mines on 22 October 1946, and 44 crew members died. Britain complained to the UN and the International Court of Justice which, in its first case ever, ruled against Tirana.

After 1946 the United States and the United Kingdom began implementing an elaborate covert plan to overthrow Albania's Communist regime by backing anti-Communist and royalist forces within the country. By 1949 the United States and British intelligence organizations were working with King Zog and the mountainmen of his personal guard. They recruited Albanian refugees and émigrés from Egypt, Italy, and Greece; trained them in Cyprus, Malta, and the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany); and infiltrated them into Albania. Guerrilla units entered Albania in 1950 and 1952, but Albanian security forces killed or captured all of them. Kim Philby, a Soviet double agent working as a liaison officer between the British intelligence service and the United States Central Intelligence Agency, had leaked details of the infiltration plan to Moscow, and the security breach claimed the lives of about 300 infiltrators.

Following a wave of subversive activity, including the failed infiltration and the March 1951 bombing of the Soviet embassy in Tirana, the Albanian regime implemented harsh internal security measures. In September 1952, the assembly enacted a penal code that required the death penalty for anyone over eleven years old who was found guilty of conspiring against the state, damaging state property, or committing economic sabotage. Political executions were common and between 5,000 and 25,000 people were killed in total under the period of the Communist regime.[9][10][11]

Albania in the Soviet sphere

Albania became dependent on Soviet aid and know-how after it broke with Yugoslavia in 1948. In February 1949, Albania gained membership in the communist bloc's organization for coordinating economic planning, the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (Comecon). Tirana soon entered into trade agreements with Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Romania, and the Soviet Union. Soviet and East European technical advisers took up residence in Albania, and the Soviet Union also sent Albania military advisers and built a submarine installation on Sazan Island. After the Soviet-Yugoslav split, Albania and Bulgaria remained the only countries that the Soviet Union could use to funnel war material to the communists fighting in Greece. What little strategic value Albania offered the Soviet Union, however, gradually shrank as nuclear-arms technology developed.

Anxious to pay homage to Stalin, Albania's rulers implemented elements of the Stalinist economic system. In 1949 Albania adopted the basic elements of the Soviet fiscal system, under which state enterprises paid direct contributions to the treasury from their profits and kept only a share authorized for self-financed investments and other purposes. In 1951 the Albanian government launched its first five-year plan, which emphasized exploiting the country's oil, chromite, copper, nickel, asphalt, and coal resources; expanding electricity production and the power grid; increasing agricultural output; and improving transportation. The government began a program of rapid industrialization after the APL's Second Party Congress and a campaign of forced collectivization of farmland in 1955. At the time, private farms still produced about 87% of Albania's agricultural output, but by 1960 the same percentage came from collective or state farms.

Soviet-Albanian relations remained warm during the last years of Stalin's life, although Albania was an economic liability for the Soviet Union. Albania conducted all its foreign trade with Soviet European countries in 1949, 1950, and 1951 – and over half its trade with the Soviet Union itself. Together with its satellites, the Soviet Union underwrote shortfalls in Albania's balance-of-payments with long-term grants.

Although far behind Western practice, health care and education improved dramatically for Albania's 1.2 million people in the early 1950s. The number of Albanian doctors increased by a third to about 150 early in the decade (although the doctor-patient ratio remained unacceptable by most standards), and the state opened new medical-training facilities. The number of hospital beds rose from 1,765 in 1945 to about 5,500 in 1953. Better health-care and living conditions produced an improvement in Albania's dismal infant-mortality rate, lowering it from 112.2 deaths per 1,000 live births in 1945 to 99.5 deaths per 1,000 births in 1953. The education system, considered a tool for propagating communism and creating the academic and technical cadres necessary for construction of a socialist state and society, also improved dramatically. The number of schools, teachers, and students doubled between 1945 and 1950. Illiteracy declined from perhaps 85% in 1946 to 31% in 1950. The Soviet Union provided scholarships for Albanian students and supplied specialists and study materials to improve instruction in Albania. The State University of Tirana (later the University of Tirana) was founded in 1957 and the Albanian Academy of Sciences opened 15 years later. Despite these advances, however, education in Albania suffered as a result of restrictions on freedom of thought. For example, educational institutions had scant influence on their own curricula, methods of teaching, or administration.

Stalin died in March 1953, and apparently fearing that the Soviet ruler's demise might encourage rivals within the Albanian party's ranks, neither Hoxha nor Shehu risked traveling to Moscow to attend his funeral. The Soviet Union's subsequent movement toward rapprochement with the hated Yugoslavs rankled the two Albanian leaders. Tirana soon came under pressure from Moscow to copy, at least formally, the new Soviet model for a collective leadership. In July 1953, Hoxha handed over the foreign affairs and defense portfolios to loyal followers, but he kept both the top party post and the premiership until 1954, when Shehu became Albania's prime minister. The Soviet Union, responding with an effort to raise the Albanian leaders' morale, elevated diplomatic relations between the two countries to the ambassadorial level.

Despite some initial expressions of enthusiasm, Hoxha and Shehu mistrusted Nikita Khrushchev's programs of "peaceful coexistence" and "different roads to socialism" because they appeared to pose the threat that Yugoslavia might again try to take control of Albania. It also concerned Hoxha and Shehu that Moscow might prefer less dogmatic rulers in Albania. Tirana and Belgrade renewed diplomatic relations in December 1953, but Hoxha refused Khrushchev's repeated appeals to rehabilitate posthumously the pro-Yugoslav Xoxe as a gesture to Tito. The Albanian duo instead tightened their grip on their country's domestic life and let the propaganda war with the Yugoslavs grind on. In 1955 Albania became a founding member of the Warsaw Treaty Organization, better known as the Warsaw Pact, the only military alliance the nation ever joined. Although the pact represented the first promise Albania had obtained from any of the communist countries to defend its borders, the treaty did nothing to assuage the Albanian leaders' deep mistrust of Yugoslavia.

Hoxha and Shehu tapped the Albanians' deep-seated fear of Yugoslav domination to remain in power during the thaw following the Twentieth Party Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in 1956, when Khrushchev denounced Stalin's crimes in his "secret speech". Hoxha defended Stalin and blamed the Titoist heresy for the troubles vexing world Communism, including the disturbances in Poland and the rebellion in Hungary in 1956. Hoxha mercilessly purged party moderates with pro-Soviet and pro-Yugoslav leanings, but he toned down his anti-Yugoslav rhetoric after an April 1957 trip to Moscow, where he won cancellation of about US$105 million in outstanding loans and about US$7.8 million in additional food assistance. By 1958, however, Hoxha was again complaining about Tito's "fascism" and "genocide" against Albanians in Kosovo. He also grumbled about a Comecon plan for integrating the East European economies, which called for Albania to produce agricultural goods and minerals instead of emphasizing the development of heavy industry. On a twelve-day visit to Albania in 1959, Khrushchev reportedly tried to convince Hoxha and Shehu that their country should aspire to become socialism's "orchard".

Albania in the Chinese Sphere

Albania played a role in the Sino-Soviet conflict far outweighing either its size or its importance in the Communist world. By 1958 Albania stood with the People's Republic of China (PRC)[12] in opposing Moscow on issues of peaceful coexistence, de-Stalinization, and Yugoslavia's "separate road to socialism" through decentralization of economic life. The Soviet Union, other Eastern European countries, and China all offered Albania large amounts of aid. Soviet leaders also promised to build a large Palace of Culture in Tirana as a symbol of the Soviet people's "love and friendship" for the Albanians. But despite these gestures, Tirana was dissatisfied with Moscow's economic policy toward Albania. Hoxha and Shehu apparently decided in either May or June 1960 that Albania was assured of Chinese support, and when sharp polemics erupted between the PRC and the Soviet Union, they openly sided with the former. Ramiz Alia, at the time a candidate-member of the Politburo and Hoxha's adviser on ideological questions, played a prominent role in the rhetoric.

The Sino-Soviet split burst into the open in June 1960 at a Romanian Workers' Party congress, at which Khrushchev attempted to secure condemnation of Beijing. Albania's delegation, alone among the European delegations, supported the Chinese. The Soviet Union immediately retaliated by organizing a campaign to oust Hoxha and Shehu in the summer of 1960. Moscow cut promised grain deliveries to Albania during a drought, and the Soviet embassy in Tirana overtly encouraged a pro-Soviet faction in the Party of Labour of Albania (APL) to speak out against the party's pro-Chinese stance. Moscow also apparently involved itself in a plot within the APL to unseat Hoxha and Shehu by force. But given their tight control of the party machinery, army, and Shehu's secret police, the Directorate of State Security (Drejtorija e Sigurimit të Shtetit—Sigurimi), the two Albanian leaders easily parried the threat. Four pro-Soviet Albanian leaders, including Teme Sejko and Tahir Demi, were eventually tried and executed. The PRC immediately began making up for the cancellation of Soviet wheat shipments despite a paucity of foreign currency and its own economic hardships.

Albania again sided with the People's Republic of China when it launched an attack on the Soviet Union's leadership of the international communist movement at the November 1960 Moscow conference of the world's 81 communist parties. Hoxha inveighed against Khrushchev for encouraging Greek claims to southern Albania, sowing discord within the APL and army, and using economic blackmail. "Soviet rats were able to eat while the Albanian people were dying of hunger," Hoxha railed, referring to purposely delayed Soviet grain deliveries. Communist leaders loyal to Moscow described Hoxha's performance as "gangsterish" and "infantile," and the speech extinguished any chance of an agreement between Moscow and Tirana. For the next year, Albania played proxy for Communist China. Pro-Soviet Communist parties, reluctant to confront the PRC directly, criticized Beijing by castigating Albania. Communist China, for its part, frequently gave prominence to the Albanians' fulminations against the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia, which Tirana referred to as a "socialist hell."

Hoxha and Shehu continued their harangue against the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia at the APL's Fourth Party Congress in February 1961. During the congress, the Albanian government announced the broad outlines of the country's Third Five-Year Plan (1961–65), which allocated 54% of all investment to industry, thereby rejecting Khrushchev's wish to make Albania primarily an agricultural producer. Moscow responded by canceling aid programs and lines of credit for Albania, but the Chinese again came to the rescue.

After additional sharp exchanges between Soviet and Chinese delegates over Albania at the Communist Party of the Soviet Union's Twenty-Second Party Congress in October 1961, Khrushchev lambasted the Albanians for executing a pregnant, pro-Soviet member of the Albanian party Politburo Liri Gega, and the Soviet Union finally broke diplomatic relations with Albania in December. Moscow then withdrew all Soviet economic advisers and technicians from the country, including those at work on the Palace of Culture, and halted shipments of supplies and spare parts for equipment already in place in Albania. In addition, the Soviet Union continued to dismantle its naval installations on Sazan Island, a process that had begun even before the break in relations.

Communist China again compensated Albania for the loss of Soviet economic support, supplying about 90% of the parts, foodstuffs, and other goods the Soviet Union had promised. Beijing lent the Albanians money on more favorable terms than Moscow, and, unlike Soviet advisers, Chinese technicians earned the same low pay as Albanian workers and lived in similar housing. China also presented Albania with a powerful radio transmission station from which Tirana sang the praises of Stalin, Hoxha, and Mao Zedong for decades. For its part, Albania offered China a beachhead in Europe and acted as Communist China's chief spokesman at the UN. To Albania's dismay, however, Chinese equipment and technicians were not nearly as sophisticated as the Soviet goods and advisers they replaced. Ironically, a language barrier even forced the Chinese and Albanian technicians to communicate in Russian. Albanians no longer took part in Warsaw Pact activities or Comecon agreements. The other East European communist nations, however, did not break diplomatic or trade links with Albania. In 1964, the Albanians went so far as to seize the empty Soviet embassy in Tirana, and Albanian workers pressed on with construction of the Palace of Culture on their own.

The shift away from the Soviet Union wreaked havoc on Albania's economy. Half of its imports and exports had been geared toward Soviet suppliers and markets, so the souring of Tirana's relations with Moscow brought Albania's foreign trade to near collapse as China proved incapable of delivering promised machinery and equipment on time. The low productivity, flawed planning, poor workmanship, and inefficient management at Albanian enterprises became clear when Soviet and Eastern European aid and advisers were withdrawn. In 1962, the Albanian government introduced an austerity program, appealing to the people to conserve resources, cut production costs, and abandon unnecessary investment.

Withdrawal from the Warsaw Pact

In October 1964, Hoxha hailed Khrushchev's fall from power, and the Soviet Union's new leaders made overtures to Tirana. It soon became clear, however, that the new Soviet leadership had no intention of changing basic policies to suit Albania, and relations failed to improve. Tirana's propaganda continued for decades to refer to Soviet officials as "treacherous revisionists" and "traitors to Communism," and in 1964, Hoxha said that Albania's terms for reconciliation were a Soviet apology to Albania and reparations for damages inflicted on the country. Soviet-Albanian relations dipped to new lows after the Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968, Albania felt that the Soviet Union itself had become too liberal since the death of Joseph Stalin, so it withdrew from the Warsaw Pact. Leonid Brezhnev made no attempt to force Albania to remain.

Cultural and Ideological Revolution

In the mid-1960s, Albania's leaders grew wary of a threat to their power by a burgeoning bureaucracy. Party discipline had eroded. People complained about malfeasance, inflation, and low-quality goods. Writers strayed from the orthodoxy of socialist realism, which demanded that art and literature serve as instruments of government and party policy. As a result, after Mao Zedong unleashed the Cultural Revolution in China in 1966, Hoxha launched his own Cultural and Ideological Revolution. The Albanian leader concentrated on reforming the military, government bureaucracy, and economy as well as on creating new support for his system. The regime abolished military ranks, reintroduced political commissars into the military, and renounced professionalism in the army. Railing against a "white-collar mentality," the authorities also slashed the salaries of mid- and high-level officials, ousted administrators and specialists from their desk jobs, and sent such persons to toil in the factories and fields. Six ministries, including the Ministry of Justice, were eliminated. Farm collectivization spread to even the remote mountains. In addition, the government attacked dissident writers and artists, reformed its educational system, and generally reinforced Albania's isolation from European culture in an effort to keep out foreign influences.

In 1967, the authorities conducted a violent campaign to extinguish religious life in Albania, claiming that religion had divided the Albanian nation and kept it mired in backwardness. Student agitators combed the countryside, forcing Albanians to quit practicing their faith. Despite complaints, even by APL members, all churches, mosques, monasteries, and other religious institutions were closed or converted into warehouses, gymnasiums, and workshops by year's end. A special decree abrogated the charters by which the country's main religious communities had operated. The campaign culminated in an announcement that Albania had become the world's first atheistic state, a feat trumpeted as one of Enver Hoxha's greatest achievements.

Traditional kinship links in Albania, centered on the patriarchal family, were shattered by the postwar repression of clan leaders, collectivization of agriculture, industrialization, migration from the countryside to urban areas, and suppression of religion.[13][14][15] The postwar regime brought a radical change in the status of Albania's women. Considered second-class citizens in traditional Albanian society, women performed most of the work at home and in the fields. Before World War II, about 90% of Albania's women were illiterate, and in many areas they were regarded as chattels under ancient tribal laws and customs. During the Cultural and Ideological Revolution, the party encouraged women to take jobs outside the home in an effort to compensate for labor shortages and to overcome their conservatism. Hoxha himself proclaimed that anyone who trampled on the party's edict on women's rights should be "hurled into the fire."

Albania and self-reliance

Albanian-Chinese relations had stagnated by 1970, and when the Asian giant began to reemerge from isolation and the Cultural Revolution in the early 1970s, Mao and the other Communist Chinese leaders reassessed their commitment to tiny Albania. In response, Tirana began broadening its contacts with the outside world. Albania opened trade negotiations with France, Italy, and the recently independent Asian and African states, and in 1971 it normalised relations with Yugoslavia and Greece. Albania's leaders abhorred the People's Republic of China's contacts with the United States in the early 1970s, and its press and radio ignored President Richard Nixon's trip to Beijing in 1972. Albania actively worked to reduce its dependence on Communist China by diversifying trade and by improving diplomatic and cultural relations, especially with Western Europe. But Albania shunned the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe and was the only European country that refused to take part in the Helsinki Conference of July 1975. Soon after Mao's death in 1976, Hoxha criticized the new leadership as well as Beijing's pragmatic policy toward the United States and Western Europe. The Chinese retorted by inviting Tito to visit Beijing in 1977 and ending assistance programs for Albania in 1978.

The Sino-Albanian split left Albania with no foreign benefactor. Tirana ignored calls by the United States and the Soviet Union to normalize relations. Instead, Albania expanded diplomatic ties with Western Europe and the developing nations and began stressing the principle of self-reliance as the keystone of the country's strategy for economic development. Albania, however, didn't have many resources of its own, and Hoxha's cautious opening toward the outside world wasn't enough to bolster the economy, which stirred up nascent movements for change inside Albania. Without Chinese or Soviet aid, the country began to experience widespread shortages in everything from machine parts to wheat and animal feed. Infrastructure and living standards began to collapse. According to the World bank, Albania netted around US$750 in gross national product per capita throughout much of the 1980s. As Hoxha's health slipped, muted calls arose for the relaxation of party controls and greater openness. In response, Hoxha launched a fresh series of purges that removed the defense minister and many top military officials. A year later, Hoxha purged ministers responsible for the economy and replaced them with younger people.

As Hoxha began experiencing more health problems, he progressively started withdrawing from state affairs and taking longer and more frequent leaves of absence. Meanwhile, he began planning for an orderly succession. He worked to institutionalize his policies, hoping to frustrate any attempt his successors might make to venture from the Stalinist path he had blazed for Albania. In December 1976, Albania adopted its second Stalinist constitution of the postwar era. The document guaranteed Albanians freedom of speech, the press, organization, association, and assembly but subordinated these rights to the individual's duties to society as a whole. The constitution continued to emphasize national pride and unity, and enshrined in law the idea of autarky and prohibited the government from seeking financial aid or credits or from forming joint companies with partners from capitalist or revisionist communist countries. The constitution's preamble also boasted that the foundations of religious belief in Albania had been abolished.

In 1980, Hoxha tapped Ramiz Alia to succeed him as Albania's communist patriarch, overlooking his long-standing comrade-in-arms, Mehmet Shehu. Hoxha first tried to convince Shehu to step aside voluntarily, but when this move failed, Hoxha arranged for all the members of the Politburo to rebuke him for allowing his son to become engaged to the daughter of a former bourgeois family. Shehu allegedly committed suicide on 18 December 1981. Some suspect that Hoxha had him killed. Hoxha had Shehu's wife and three sons arrested, one of whom killed himself in prison.[16] In November 1982, Hoxha announced that Shehu had been a foreign spy working simultaneously for the United States, British, Soviet, and Yugoslav intelligence agencies in planning the assassination of Hoxha himself. "He was buried like a dog," Hoxha wrote in the Albanian edition of his book, The Titoites.

Hoxha relinquished many duties in 1983 due to poor health, and Alia assumed responsibility for Albania's administration. Alia traveled extensively around Albania, standing in for Hoxha at major events and delivering addresses laying down new policies and intoning litanies to the enfeebled president. Hoxha died on 11 April 1985. Alia succeeded to the presidency and became legal secretary of the APL two days later. In due course, he became a dominant figure in the Albanian media, and his slogans were painted in crimson letters on signboards across the country.

Transition

After Hoxha's death, Ramiz Alia maintained firm control of the country and its security apparatus, but Albania's desperate economic situation required Alia to introduce some reform. Continuing a policy set by Hoxha, Alia reestablished diplomatic relations with West Germany in return for development aid and he courted Italy and France.[16] The very gradual and slight reforms intensified as Mikhail Gorbachev introduced his new policies of glasnost and perestroika in the Soviet Union, culminating in the fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989 and the collapse of communist governments across Central and Eastern Europe.

After Nicolae Ceauşescu (the communist leader of Romania) was executed in a revolution in 1989, Alia expedited his reforms, apparently concerned about violence and his own fate if radical changes were not made. He signed the Helsinki Agreement (which was signed by other countries in 1975) that respected some human rights. On 11 December 1990, under enormous pressure from students and workers, Alia announced that the Party of Labor had abandoned its guaranteed right to rule, that other parties could be formed, and that free elections would be held in the spring of 1991.

Alia's party won the elections on 31 March 1991—the first free elections held in decades.[17] Nevertheless, it was clear that the change would not be stopped. The position of the communists was confirmed in the first round of elections under a 1991 interim law, but fell two months later during a general strike. A committee of "national salvation" took over but also collapsed within six months. On 22 March 1992, the Communists were trumped by the Democratic Party in national elections.[4] The change from dictatorship to democracy had many challenges. The Democratic Party had to implement the reforms it had promised, but they were either too slow or did not solve the problems, so people were disappointed when their hopes for fast prosperity went unfulfilled.

In the general elections of June 1996 the Democratic Party tried to win an absolute majority and manipulated the results. This government collapsed in 1997 in the wake of additional collapses of pyramid schemes and widespread corruption, which caused chaos and rebellion throughout the country. The government attempted to suppress the rebellion by military force but the attempt failed, due to long-term corruption of the armed forces, forcing other nations to intervene. Pursuant to the 1991 interim basic law, Albanians ratified a constitution in 1998, establishing a democratic system of government based upon the rule of law and guaranteeing the protection of fundamental human rights.[18]

Legacy

Policies pursued by Enver Hoxha and his followers influenced the political and economic thought around the world. Thus, based on the ideas of Enver Hoxha for the construction of the communist state and the strict adherence to Marxism–Leninism there were created the Hoxhaist parties in many countries around the world. Following the fall of the People's Socialist Republic of Albania in 1991, the Hoxhaist parties grouped themselves around an International conference and the publication Unity and Struggle.

List of leaders

General Secretaries of the Party of Labour of Albania:

- Enver Hoxha (1946–1985)

- Ramiz Alia (1985–1991)

Chairmen of the Presidium of the People's Assembly:

- Omer Nishani (1946–1953)

- Haxhi Lleshi (1953–1982)

- Ramiz Alia (1982–1991)

- Enver Hoxha (1946–1954)

- Mehmet Shehu (1954–1981)

- Adil Çarçani (1981–1991)

Military

See also

Notes

- ↑ Giacomo Jungg (1 January 1895). "Fialuur i voghel scc...p e ltinisct mle...un prei P. Jak Junkut t' Scocniis ...". N'Sckoder t' Scc...pniis. Retrieved 23 July 2016 – via Internet Archive.

- ↑ Kushtetuta e Republikës Popullore Socialiste të Shqipërisë: miratuar nga Kuvendi Popullor më 28. 12. 1976

- ↑ Majeska, George P. (1976). "Religion and Atheism in the U.S.S.R. and Eastern Europe, Review". The Slavic and East European Journal. 20(2). pp. 204–206.

- 1 2 http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/journal_of_democracy/election_watch/v003/index.html#v003.3

- ↑ Robert Elsie (2012), A Biographical Dictionary of Albanian History, I. B. Tauris, p. 388, ISBN 978-1780764313,

...the Treason Trial conducted by the Special Court (Gjyqi Special), at which 60 members of the pre-Communist establishment were sentenced to death and long prison sentences as war criminals and enemies of the people

- ↑ Albania: From Anarchy to a Balkan Identity; by Miranda Vickers & James Pettifer, 1999 ISBN 1-85065-279-1; p. 222 "the French Communist Party, then ultra-Stalinist in orientation. He may have owed some aspects of his political thought and general psychology to that"

- ↑ Owen Pearson: Albania As Dictatorship And Democracy. London 2006, S. 238.

- ↑ Zitat nach: G. H. Hodos: Schauprozesse. Berlin 2001, S. 34.

- ↑ 15 Feb 1994 Washington Times

- ↑ "WHPSI": The World Handbook of Political and Social Indicators by Charles Lewis Taylor

- ↑ 8 July 1997 NY Times

- ↑ Albania: From Anarchy to a Balkan Identity; by Miranda Vickers & James Pettifer, 1999 ISBN 1-85065-279-1; p. 210 "with the split in the world communist movement it moved into a close relationship with China"

- ↑ Albania: From Anarchy to a Balkan Identity; by Miranda Vickers & James Pettifer, 1999 ISBN 1-85065-279-1; p. 138 "Because of its association with the years of repression under communism, Albanians have developed an aversion to collective life in any form, even where it"

- ↑ Albania: From Anarchy to a Balkan Identity; by Miranda Vickers & James Pettifer, 1999 ISBN 1-85065-279-1; p. 2 "Enver Hoxha's regime was haunted by fears of external intervention and internal subversion. Albania thus became a fortress state"

- ↑ The Greek Minority in Albania – In the Aftermath of Communism "Onset in 1967 of the campaign by Albania’s communist party, the Albanian Party of Labour (PLA), to eradicate organised religion, a prime target of which was the Orthodox Church.Many churches were damaged or destroyed during this period, and many Greek-language books were banned because of their religious themes or orientation. Yet, as with other Communist states, particularly in the Balkans, where measures putatively geared towards the consolidation of political control intersected with the pursuit of national integration, it is often impossible to distinguish sharply between ideological and ethno-cultural bases of repression. This is all the more true in the case of Albania’s anti-religion campaign because it was merely one element in the broader “Ideological and Cultural Revolution” begun by Hoxha in 1966 but whose main features he outlined at the PLA’s Fourth Congress in 1961"

- 1 2 Abrahams, Fred C (2015). [modern-albania.com Modern Albania: From Dictatorship to Democracy] Check

|url=value (help). NYU Press. pp. 28–29. ISBN 9780814705117. - ↑ http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/journal_of_democracy/election_watch/v002/index.html

- ↑ "Albania 1998 (rev. 2008)". Constitute. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

References

- Library of Congress Country Study of Albania

- Afrim Krasniqi, Political Parties in Albania 1912–2006, Rilindje, 2007

- Afrim Krasniqi, Political System in Albania 1912–2008, Ufo press, 2010

.svg.png)