Hippie trail

The hippie trail (also the overland[1]) is the name given to the overland journey taken by members of the hippie subculture and others from the mid-1950s to the late 1970s[2] between Europe and South Asia, mainly Pakistan, India and Nepal. The hippie trail was a form of alternative tourism, and one of the key elements was travelling as cheaply as possible, mainly to extend the length of time away from home. The term "hippie" became current from the mid- to late 1960s; "beatnik" was the previous term which had gained currency in the second half of the 1950s.

In every major stop of the hippie trail, there were hotels, restaurants and cafés that catered almost exclusively to Westerners, who networked with each other as they travelled east and west. The hippies tended to spend more time interacting with the local population than traditional sightseeing tourists.[1]

Routes

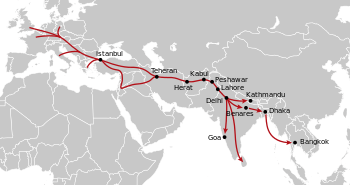

Journeys would typically start from cities in western Europe, often London, Copenhagen, West Berlin, Paris, Amsterdam, or Milan. Many from the United States took Icelandic Airlines to Luxembourg. Most journeys passed through Istanbul, where routes divided. The usual northern route passed through Tehran, Herat, Kandahar, Kabul, Peshawar and Lahore on to India, Nepal and Southeast Asia. An alternative route was from Turkey via Syria, Jordan, and Iraq to Iran and Pakistan. All travellers had to cross the Pakistan-India border at Ganda Singh Wala (or later at Wagah). Delhi, Varanasi (then Benares), Goa, Kathmandu, or Bangkok were the usual destinations in the east. Kathmandu still has a road, Jhochhen Tole, nicknamed Freak Street in commemoration of the many thousands of hippies who passed through. Further travel to southern India, Kovalam beach in Trivandrum (Kerala) and some to Sri Lanka (then called Ceylon), and points east and south to Australia was sometimes also undertaken.

Cities

Methods of travel

In order to keep costs low, journeys were carried out by hitchhiking, or cheap, private buses that travelled the route. There were also trains that travelled part of the way, particularly across Eastern Europe through Turkey (with a ferry connection across Lake Van) and to Tehran or east to Mashhad, Iran. From these cities, public or private transportation could then be obtained for the rest of the trip. The bulk of travellers comprised Western Europeans, North Americans, Australians, and Japanese. Ideas and experiences were exchanged in well-known hostels, hotels, and other gathering spots along the way, such as Yener's Café and The Pudding Shop in Istanbul, Sigi's on Chicken Street in Kabul or the Amir Kabir in Tehran. Many used backpacks and, while the majority were young, older people and families occasionally travelled the route. A number drove the entire distance.

Hippies tended to travel light, seeking to pick up and go wherever the action was at any time. Hippies did not worry about money, hotel reservations or other such standard travel planning. A derivative of this style of travel were the hippie trucks and buses, hand-crafted mobile houses built on a truck or bus chassis to facilitate a nomadic lifestyle.[3] Some of these mobile homes were quite elaborate, with beds, toilets, showers and cooking facilities.

Decline and revival of the trail

The hippie trail came to an end in the late 1970s with political changes in previously hospitable countries. In 1979, both the Iranian Revolution[4] and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan closed the overland route to Western travelers. The Yom Kippur War also put in place strict visa restrictions for Western citizens in Syria, Iraq and Lebanon. The Lebanese Civil War had already broken out in 1975, and Chitral and Kashmir became less inviting due to tensions in the area.[1]

Locals also became increasingly annoyed with Western travelers – notably in the region between Kabul and Peshawar, where residents became increasingly frightened and repulsed by unkempt hippies who were drawn to the region for its famed opium and wild cannabis.[5] Travel organizers Sundowners and Topdeck pioneered a route through Baluchistan. Topdeck continued its trips throughout the Iran–Iraq War and later conflicts, but took its last trip in 1998.

From the mid 2000s, the route has again become somewhat feasible, but continuing conflict and tensions in Iraq, Afghanistan and parts of Pakistan mean the route is much more difficult and risky to negotiate than in its heyday. In September 2007, Ozbus embarked upon a short-lived service between London and Sydney over the route of the hippie trail,[6] and commercial trips are now offered between Europe and Asia, bypassing Iraq, Afghanistan, and Pakistan, by going through Nepal and Tibet to the old Silk Road .[7]

Guides and travelogues

The BIT Guide, recounting collective experiences and reproduced at a fairly low cost, produced the early duplicated stapled-together "foolscap bundle" with a pink cover providing information for travelers and updated by those on the road, warning of pitfalls and places to see and stay. BIT, under Geoff Crowther (who later joined Lonely Planet), lasted from 1972 until the last edition in 1980.[8] The 1971 edition of The Whole Earth Catalog devoted a page[9] to the "Overland Guide to Nepal." In 1973 Tony Wheeler and his wife Maureen Wheeler, the creators of the Lonely Planet guidebooks, produced a publication about the hippie trail called Across Asia On The Cheap. They wrote this 94-page pamphlet based upon travel experiences gained by crossing Western Europe, the Balkans, Turkey and Iran from London in a minivan. After having traveled through these regions, they sold the van in Afghanistan and continued on a succession of chicken buses, third-class trains and long-distance trucks. They crossed Pakistan, India, Nepal, Thailand, Malaysia and Indonesia and arrived nine months later in Sydney with a combined 27 cents in their pockets.[10]

Paul Theroux wrote a classic account of the route in The Great Railway Bazaar (1975). Two more recent travel books — The Wrong Way Home (1999) by Peter Moore and Magic Bus (2008) by Rory Maclean — also retrace the original hippie trail.[11][12]

In popular culture

Hare Rama Hare Krishna is a 1971 Indian film directed by Dev Anand and starring him, Mumtaz and Zeenat Aman. The movie dealt with the decadence of hippie culture. It aimed to have an anti-drug message and depicts some problems associated with Westernization such as divorce. It is loosely based on the 1968 movie Psych-Out. The story for Hare Rama Hare Krishna came to Anand when he saw hippies and their values in Kathmandu. The film was a hit,[13] and Asha Bhosle's song "Dum Maro Dum" was a huge hit.

The 1981 song "Down Under" by the Australian rock band, Men at Work, sets out with a scene on the hippie trail while under the influence of marijuana:

Travelling in a fried-out Kombi, on a hippie trail, head full of zombie.

See also

- Association of Special Fares Agents

- Grand Tour – 17th–19th century Continental tour undertaken by young European aristocrats, partly as leisure and partly educational.

- Indomania

- Banana Pancake Trail

- Gringo Trail

- Silk Road

- AH1

- Lonely Planet

- Oxford and Cambridge Far Eastern Expedition

References

- 1 2 3 "A Brief History of the Hippie Trail". Retrieved 8 May 2015.

- ↑ Ireland, Brian. "Touch the Sky: the Hippie Trail and other forms of alternative tourism". Retrieved 30 January 2017.

- ↑ "Book Review - Roll Your Own". MrSharkey.Com. Archived from the original on 2012-11-02. Retrieved 2012-11-21.

- ↑ Kurzman, Charles, The Unthinkable Revolution in Iran, Harvard University Press, 2004, p.111

- ↑ Schofield, Victoria (2010). Afghan Frontier: At the Crossroads of Conflict. Tauris Parke Paperbacks. ISBN 9781848851887. Retrieved 14 June 2017.

- ↑ Anita Sethi. "End of the road for the OzBus after 84 days of mishaps and mayhem". the Guardian. Retrieved 8 May 2015.

- ↑ "Overland Tours - Overlanding Expeditions - Overland Adventure Holidays". Retrieved 8 May 2015.

- ↑ "Before Lonely Planet there was the BIT Guides". crowthercollective.org/Ashley Crowther. Retrieved 8 November 2016.

- ↑ Page 302

- ↑ Across Asia on the Cheap

- ↑ "The Wrong Way Home". Retrieved 8 May 2015.

- ↑ Magic Bus

- ↑ BoxOffice India.com Archived 2013-09-27 at the Wayback Machine.

Further reading

- MacLean, Rory (2008), Magic Bus: On the Hippie Trail from Istanbul to India, London, New York: Penguin Books, Ig Publishing.

- Brosnahan, Tom (2004), Turkey: Bright Sun, Strong Tea: on the Road with a Travel Writer, Istanbul, New York: Homer Kitabevi, Travel Info Exchange.

- Dring, Simon (1995) On the Road Again BBC Books ISBN 0-563-37172-2

- A Season in Heaven: True Tales from the Road to Kathmandu (ISBN 0864426291; compiled by David Tomory) - accounts by people who made the trip, mostly in search of enlightenment.

- Hall, Michael (2007) Remembering the Hippie Trail: travelling across Asia 1976-1978, Island Publications ISBN 978-1-899510-77-1

- Silberman, Dan (2013) In the Footsteps of Iskander: Going to India, Amazon.com, Amazon.UK ISBN 978-1-61296-246-7

External links

- Cheltenham to Delhi: Overland in a van 2007-2008

- "Road to Goa - pics and stories from a 70s 'trail' bus driver"

- Magic Bus - Asia Overland hippie trail website and photo gallery

- "The Hippie Trail - The Road to Paradise"

- Steve Abrams' Diary of trip from 1967

- "Beyond the Beach - An Ethnography of Modern Travellers in Asia"

- "On the Hippie Trail" - an impression from 1968

- Overland from London to Kathmandu in a Double Decker bus 1980-1981

- Alternative Society 1970s: BIT Travel Guide

- Video footage of Hippie Kathmandu from 1975