Hindu deities

Hindu deities are the gods and goddesses in Hinduism. The terms and epithets for deity within the diverse traditions of Hinduism vary, and include Deva, Devi, Ishvara, Bhagavan and Bhagavathi.[1][2][note 1]

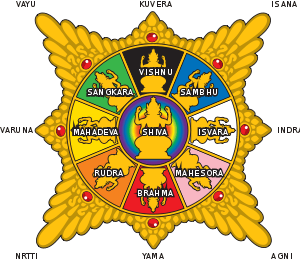

The deities of Hinduism have evolved from the Vedic era (2nd millennium BCE) through the medieval era (1st millennium CE), regionally within Nepal, India and in southeast Asia, and across Hinduism's diverse traditions.[3][4] The Hindu deity concept varies from a personal god as in Yoga school of Hindu philosophy,[5][6] to 33 Vedic deities,[7] to hundreds of Puranics of Hinduism.[8] Illustrations of major deities include Vishnu, Sri (Lakshmi), Shiva, Parvati (Durga), Brahma and Saraswati. These deities have distinct and complex personalities, yet are often viewed as aspects of the same Ultimate Reality called Brahman.[9][note 2] From ancient times, the idea of equivalence has been cherished for all Hindus, in its texts and in early 1st millennium sculpture with concepts such as Harihara (half Shiva, half Vishnu),[10] Ardhanarishvara (half Shiva, half Parvati) or Vaikuntha Kamalaja (half Vishnu, half Lakshmi),[11] with myths and temples that feature them together, declaring they are the same.[12][13][14] Major deities have inspired their own Hindu traditions, such as Vaishnavism, Shaivism and Shaktism, but with shared mythology, ritual grammar, theosophy, axiology and polycentrism.[15][16][17] Some Hindu traditions such as Smartism from mid 1st millennium CE, have included multiple major deities as henotheistic manifestations of Saguna Brahman, and as a means to realizing Nirguna Brahman.[18][19][20]

Hindu deities are represented with various icons and anicons, in paintings and sculptures, called Murtis and Pratimas.[21][22][23] Some Hindu traditions, such as ancient Charvakas rejected all deities and concept of god or goddess,[24][25][26] while 19th-century British colonial era movements such as the Arya Samaj and Brahmo Samaj rejected deities and adopted monotheistic concepts similar to Abrahamic religions.[27][28] Hindu deities have been adopted in other religions such as Jainism,[29] and in regions outside India such as predominantly Buddhist Thailand and Japan where they continue to be revered in regional temples or arts.[30][31][32]

In ancient and medieval era texts of Hinduism, the human body is described as a temple,[33][34] and deities are described to be parts residing within it,[35][36] while the Brahman (Absolute Reality, God)[18][37] is described to be the same, or of similar nature, as the Atman (self, soul), which Hindus believe is eternal and within every living being.[38][39][40] Deities in Hinduism are as diverse as its traditions, and a Hindu can choose to be polytheistic, pantheistic, monotheistic, monistic, agnostic, atheistic or humanist.[41][42][43]

Devas and devis

Deities in Hinduism are referred to as Deva (masculine) and Devi (feminine).[44][45][46] The root of these terms mean "heavenly, divine, anything of excellence".[47] According to Douglas Harper, the etymological roots of Deva mean "a shining one," from *div- "to shine," and it is a cognate with Greek dios "divine" and Zeus, and Latin deus (Old Latin deivos).[48]

In the earliest Vedic literature, all supernatural beings are called Asuras.[49][50] By the late Vedic period (~500 BCE), benevolent supernatural beings are referred to as Deva-Asuras. In post-Vedic texts, such as the Puranas and the Itihasas of Hinduism, the Devas represent the good, and the Asuras the bad.[3][4] In some medieval Indian literature, Devas are also referred to as Suras and contrasted with their equally powerful, but malevolent half-brothers referred to as the Asuras.[51]

Hindu deities are part of Indian mythology, both Devas and Devis feature in one of many cosmological theories in Hinduism.[52][53]

Characteristics of Vedic era deities

In Vedic literature, Devas and Devis represent the forces of nature and some represent moral values (such as the Adityas, Varuna, and Mitra), each symbolizing the epitome of a specialized knowledge, creative energy, exalted and magical powers (Siddhis).[54][55]

The most referred to Devas in the Rig Veda are Indra, Agni (fire) and Soma, with "fire deity" called the friend of all humanity, it and Soma being the two celebrated in a yajna fire ritual that marks major Hindu ceremonies. Savitr, Vishnu, Rudra (later given the exclusive epithet of Shiva), and Prajapati (later Brahma) are gods and hence Devas.[30]

The Vedas describes a number of significant Devis such as Ushas (dawn), Prithvi (earth), Aditi (cosmic moral order), Saraswati (river, knowledge), Vāc (sound), Nirṛti (destruction), Ratri (night), Aranyani (forest), and bounty goddesses such as Dinsana, Raka, Puramdhi, Parendi, Bharati, Mahi among others are mentioned in the Rigveda.[58] Sri, also called Lakshmi, appears in late Vedic texts dated to be pre-Buddhist, but verses dedicated to her do not suggest that her characteristics were fully developed in the Vedic era.[59] All gods and goddesses are distinguished in the Vedic times, but in the post-Vedic texts (~500 BCE to 200 CE), and particularly in the early medieval era literature, they are ultimately seen as aspects or manifestations of one Brahman, the Supreme power.[59][60]

Ananda Coomaraswamy states that Devas and Asuras in the Vedic lore are similar to Angels-Theoi-Gods and Titans of Greek mythology, both are powerful but have different orientations and inclinations, the Devas representing the powers of Light and the Asuras representing the powers of Darkness in Hindu mythology.[61][62] According to Coomaraswamy's interpretation of Devas and Asuras, both these natures exist in each human being, the tyrant and the angel is within each being, the best and the worst within each person struggles before choices and one's own nature, and the Hindu formulation of Devas and Asuras is an eternal dance between these within each person.[63][64]

The Devas and Asuras, Angels and Titans, powers of Light and powers of Darkness in Rigveda, although distinct and opposite in operation, are in essence consubstantial, their distinction being a matter not of essence but of orientation, revolution or transformation. In this case, the Titan is potentially an Angel, the Angel still by nature a Titan; the Darkness in actu is Light, the Light in potentia Darkness; whence the designations Asura and Deva may be applied to one and the same Person according to the mode of operation, as in Rigveda 1.163.3, "Trita art thou (Agni) by interior operation".

— Ananda Coomaraswamy, Journal of the American Oriental Society[65]

Characteristics of medieval era deities

In the Puranas and the Itihasas with the embedded Bhagavad Gita, the Devas represent the good, and the Asuras the bad.[3][4] According to the Bhagavad Gita (16.6-16.7), all beings in the universe have both the divine qualities (daivi sampad) and the demonic qualities (asuri sampad) within each.[4][66] The sixteenth chapter of the Bhagavad Gita states that pure god-like saints are rare and pure demon-like evil are rare among human beings, and the bulk of humanity is multi-charactered with a few or many faults.[4] According to Jeaneane Fowler, the Gita states that desires, aversions, greed, needs, emotions in various forms "are facets of ordinary lives", and it is only when they turn to lust, hate, cravings, arrogance, conceit, anger, harshness, hypocrisy, violence, cruelty and such negativity- and destruction-inclined that natural human inclinations metamorphose into something demonic (Asura).[4][66]

The Epics and medieval era texts, particularly the Puranas, developed extensive and richly varying mythologies associated with Hindu deities, including their genealogies.[67][68][69] Several of the Purana texts are named after major Hindu deities such as Vishnu, Shiva and Devi.[67] Other texts and commentators such as Adi Shankara explain that Hindu deities live or rule over the cosmic body as well in the temple of human body.[33][70] They remark that the Sun deity is the giver of vision, the Vayu deity the nose, the Prajapati the sexual organs, the Lokapalas (directions) are the ears, moon deity the mind, Mitra deity is the inward breath, Varuna deity is the outward breath, Indra deity the arms, Brhaspati the speech, Vishnu whose stride is great is the feet, and Maya is the smile.[70]

Symbolism

Edelmann states that gods and anti-gods of Hinduism are symbolism for spiritual concepts. For example, god Indra (a Deva) and the antigod Virocana (an Asura) question a sage for insights into the knowledge of the self.[71] Virocana leaves with the first given answer, believing now he can use the knowledge as a weapon. In contrast, Indra keeps pressing the sage, churning the ideas, and learning about means to inner happiness and power. Edelmann suggests that the Deva-Asura dichotomies in Hindu mythology may be seen as "narrative depictions of tendencies within our selves".[71] Hindu deities in Vedic era, states Mahoney, are those artists with "powerfully inward transformative, effective and creative mental powers".[72]

In Hindu mythology, everyone starts as an Asura, born of the same father. "Asuras who remain Asura" share the character of powerful beings craving for more power, more wealth, ego, anger, unprincipled nature, force and violence.[73][74] The "Asuras who become Devas" in contrast are driven by an inner voice, seek understanding and meaning, prefer moderation, principled behavior, aligned with Ṛta and Dharma, knowledge and harmony.[73][74][75]

The god (Deva) and antigod (Asura), states Edelmann, are also symbolically the contradictory forces that motivate each individual and people, and thus Deva-Asura dichotomy is a spiritual concept rather than mere genealogical category or species of being.[76] In the Bhāgavata Purana, saints and gods are born in families of Asuras, such as Mahabali and Prahlada, conveying the symbolism that motivations, beliefs and actions rather than one's birth and family circumstances define whether one is Deva-like or Asura-like.[76]

Ishvara

Another Hindu term that is sometimes translated as deity is Ishvara, or alternatively various deities are described, state Sorajjakool et al., as "the personifications of various aspects of one and the same Ishvara".[77] The term Ishvara has a wide range of meanings that depend on the era and the school of Hinduism.[78][79][80] In ancient texts of Indian philosophy, Ishvara means supreme soul, Brahman (Highest Reality), ruler, king or husband depending on the context.[78] In medieval era texts, Ishvara means God, Supreme Being, personal god, or special Self depending on the school of Hinduism.[2][80][81]

Among the six systems of Hindu philosophy, Samkhya and Mimamsa do not consider the concept of Ishvara, i.e., a supreme being, relevant. Yoga, Vaisheshika, Vedanta and Nyaya schools of Hinduism discuss Ishvara, but assign different meanings.

Early Nyaya school scholars considered the hypothesis of a deity as a creator God with the power to grant blessings, boons and fruits; but these early Nyaya scholars then rejected this hypothesis, and were non-theistic or atheists.[25][82] Later scholars of Nyaya school reconsidered this question and offered counter arguments for what is Ishvara and various arguments to prove the existence of omniscient, omnipresent, omnipotent deity (God).[83]

Vaisheshika school of Hinduism, as founded by Kanada in 1st millennium BC, neither required nor relied on creator deity.[84][85] Later Vaisheshika school adopted the concept of Ishvara, states Klaus Klostermaier, but as an eternal God who co-exists in the universe with eternal substances and atoms, but He "winds up the clock, and lets it run its course".[84]

Ancient Mimamsa scholars of Hinduism questioned what is Ishvara (deity, God)?[86] They considered deity concept unnecessary for a consistent philosophy and moksha (soteriology).[86][87]

In Samkhya school of Hindu philosophy, Isvara is neither a creator-God, nor a savior-God.[88] This is called one of the several major atheistic schools of Hinduism by some scholars.[89][90][91] Others, such as Jacobsen, state that Samkhya is more accurately described as non-theistic.[92] Deity is considered an irrelevant concept, neither defined nor denied, in Samkhya school of Hindu philosophy.[93]

In Yoga school of Hinduism, it is any "personal deity" (Ishta Deva or Ishta Devata)[94] or "spiritual inspiration", but not a creator God.[81][89] Whicher explains that while Patanjali's terse verses in the Yogasutras can be interpreted both as theistic or non-theistic, Patanjali's concept of Isvara in Yoga philosophy functions as a "transformative catalyst or guide for aiding the yogin on the path to spiritual emancipation".[95]

The Advaita Vedanta school of Hinduism asserted that there is no dualistic existence of deity (or deities).[96][97] There is no otherness nor distinction between Jiva and Ishvara.[98][99] God (Ishvara, Brahman) is identical with the Atman (soul) within each human being in Advaita Vedanta school,[100] and there is a monistic Universal Absolute Oneness that connects everyone and everything, states this school of Hinduism.[39][99][101] This school, states Anantanand Rambachan, has "perhaps exerted the most widespread influence".[102]

The Dvaita sub-school of Vedanta Hinduism, founded in medieval era, Ishvara is defined as a creator God that is distinct from Jiva (individual souls in living beings).[40] In this school, God creates individual souls, but the individual soul never was and never will become one with God; the best it can do is to experience bliss by getting infinitely close to God.[20]

Number of deities

|

Sri Yantra symbolizing the goddess Tripura Sundari | |

| Yantras or mandalas (shown) are 3-D images.[103] In Tantra, a minority tradition in Hinduism,[104] they are considered identical with deity.[105] Similar tantric yantras are found in Jainism and Buddhism as well.[106] |

Yāska, the earliest known language scholar of India (~ 500 BCE), notes Wilkins, mentions that there are three deities (Devas) according to the Vedas, "Agni (fire), whose place is on the earth; Vayu (wind), whose place is the air; and Surya (sun), whose place is in the sky".[107] This principle of three worlds (or zones), and its multiples is found thereafter in many ancient texts. The Samhitas, which are the oldest layer of text in Vedas enumerate 33 devas,[note 3] either 11 each for the three worlds, or as 12 Adityas, 11 Rudras, 8 Vasus and 2 Ashvins in the Brahmanas layer of Vedic texts.[7][47]

The Rigveda states in hymn 1.139.11,

ये देवासो दिव्येकादश स्थ पृथिव्यामध्येकादश स्थ ।

अप्सुक्षितो महिनैकादश स्थ ते देवासो यज्ञमिमं जुषध्वम् ॥११॥[1]

O ye eleven gods whose home is heaven, O ye eleven who make earth your dwelling,

Ye who with might, eleven, live in waters, accept this sacrifice, O gods, with pleasure.

– Translated by Ralph T. H. Griffith[2]

Gods who are eleven in heaven; who are eleven on earth;

and who are eleven dwelling with glory in mid-air; may ye be pleased with this our sacrifice.

– Translated by HH Wilson[3]

- ^ ऋग्वेद: सूक्तं १.१३९ Sanskrit, Wikisource

- ^ The Rig Veda/Mandala 1/Hymn 139 Verse 11, Ralph T. H. Griffith, Wikisource

- ^ The Rig Veda Samhita Verse 11, HH Wilson (Translator), Royal Asiatic Society, WH Allen & Co, London

— Rigveda 1.139.11

Millions, one or one-ness

Thirty-three divinities are mentioned in other ancient texts, such as the Yajurveda,[111] however, there is no fixed "number of deities" in Hinduism any more than a standard representation of "deity".[112] There is, however, a popular perception stating that there are 330 million (or "33 crore") deities in Hinduism.[113] Most, by far, are goddesses, state Foulston and Abbott, suggesting "how important and popular goddesses are" in Hindu culture.[112] No one has a list of the 330 million goddesses and gods, but all deities, state scholars, are typically viewed in Hinduism as "emanations or manifestation of genderless principle called Brahman, representing the many facets of Ultimate Reality".[112][113][114]

This concept of Brahman is not the same as the monotheistic separate God found in Abrahamic religions, where God is considered, states Brodd, as "creator of the world, above and independent of human existence", while in Hinduism "God, the universe, human beings and all else is essentially one thing" and everything is connected oneness, the same god is in every human being as Atman, the eternal Self.[114][115]

Iconography and practices

Oh Tree! you have been selected for the worship of a deity,

Salutations to you!

I worship you per rules, kindly accept it.

May all who live in this tree, find residence elsewhere,

May they forgive us now, we bow to them.

Hinduism has an ancient and extensive iconography tradition, particularly in the form of Murti (Sanskrit: मूर्ति, IAST: Mūrti), or Vigraha or Pratima.[22] A Murti is itself not the god in Hinduism, but it is an image of god and represents emotional and religious value.[121] A literal translation of Murti as idol is incorrect, states Jeaneane Fowler, when idol is understood as superstitious end in itself.[121] Just like the photograph of a person is not the real person, a Murti is an image in Hinduism but not the real thing, but in both cases the image reminds of something of emotional and real value to the viewer.[121] When a person worships a Murti, it is assumed to be a manifestation of the essence or spirit of the deity, the worshipper's spiritual ideas and needs are meditated through it, yet the idea of ultimate reality or Brahman is not confined in it.[121]

A Murti of a Hindu deity is typically made by carving stone, wood working, metal casting or through pottery. Medieval era texts describing their proper proportions, positions and gestures include the Puranas, Agamas and Samhitas particularly the Shilpa Shastras.[21] The expressions in a Murti vary in diverse Hindu traditions, ranging from Ugra symbolism to express destruction, fear and violence (Durga, Kali), as well as Saumya symbolism to express joy, knowledge and harmony (Saraswati, Lakshmi). Saumya images are most common in Hindu temples.[122] Other Murti forms found in Hinduism include the Linga.[123]

A Murti is an embodiment of the divine, the Ultimate Reality or Brahman to some Hindus.[21] In religious context, they are found in Hindu temples or homes, where they may be treated as a beloved guest and serve as a participant of Puja rituals in Hinduism.[124] A murti is installed by priests, in Hindu temples, through the Prana Pratishtha ceremony,[125] whereby state Harold Coward and David Goa, the "divine vital energy of the cosmos is infused into the sculpture" and then the divine is welcomed as one would welcome a friend.[126] In other occasions, it serves as the center of attention in annual festive processions and these are called Utsava Murti.[127]

Temple and worship

In Hinduism, deities and their icons may be hosted in a Hindu temple, within a home or as an amulet. The worship performed by Hindus is known by a number of regional names, such as Puja.[131] This practice in front of a murti may be elaborate in large temples, or be a simple song or mantra muttered in home, or offering made to sunrise or river or symbolic anicon of a deity.[132][133][134] Archaeological evidence of deity worship in Hindu temples trace Puja rituals to Gupta Empire era (~4th century CE).[135][136] In Hindu temples, various pujas may be performed daily at various times of the day; in other temples, it may be occasional.[137][138]

The Puja practice is structured as an act of welcoming, hosting, honoring the deity of one's choice as one's honored guest,[139] and remembering the spiritual and emotional significance the deity represents the devotee.[121][131] Jan Gonda, as well as Diana L. Eck, states that a typical Puja involves one or more of 16 steps (Shodasha Upachara) traceable to ancient times: the deity is invited as a guest, the devotee hosts and takes care of the deity as an honored guest, praise (hymns) with Dhupa or Aarti along with food (Naivedhya) is offered to the deity, after an expression of love and respect the host takes leave, and with affection expresses good bye to the deity.[140][141] The worship practice may also involve reflecting on spiritual questions, with image serving as support for such meditation.[142]

Deity worship (Bhakti), visiting temples and Puja rites are not mandatory and is optional in Hinduism; it is the choice of a Hindu, it may be a routine daily affair for some Hindus, periodic ritual or infrequent for some.[143][144] Worship practices in Hinduism are as diverse as its traditions, and a Hindu can choose to be polytheistic, pantheistic, monotheistic, monistic, agnostic, atheistic, or humanist.[41]

Examples

Major deities have inspired a vast genre of literature such as the Puranas and Agama texts as well their own Hindu traditions, but with shared mythology, ritual grammar, theosophy, axiology and polycentrism.[16][17] Vishnu and his avatars are at the foundation of Vaishnavism, Shiva for Shaivism, Devi for Shaktism, and some Hindu traditions such as Smarta traditions who revere multiple major deities (five) as henotheistic manifestations of Brahman (absolute metaphysical Reality).[113][145][146]

While there are diverse deities in Hinduism, states Lawrence, "Exclusivism – which maintains that only one's own deity is real" is rare in Hinduism.[113] Julius Lipner, and other scholars, state that pluralism and "polycentrism" – where other deities are recognized and revered by members of different "denominations", has been the Hindu ethos and way of life.[16][147]

Trimurti and Tridevi

The concept of Triad (or Trimurti, Trinity) makes a relatively late appearance in Hindu literature, or in the second half of 1st millennium BCE.[148] The idea of triad, playing three roles in the cosmic affairs, is typically associated with Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva (also called Mahesh); however, this is not the only triad in Hindu literature.[149] Other triads include Tridevi, of three goddesses – Lakshmi, Saraswati and Durga in the text Devi Mahatmya, in the Shakta tradition, who further assert that Devi is the Brahman (Ultimate Reality) and it is her energy that empowers Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva.[148] The other triads, formulated as deities in ancient Indian literature, include Sun (creator), Air (sustainer) and Fire (destroyer); Prana (creator), Food (sustainer) and Time (destroyer).[148] These triads, states Jan Gonda, are in some mythologies grouped together without forming a Trinity, and in other times represented as equal, a unity and manifestations of one Brahman.[148] In the Puranas, for example, this idea of threefold "hypostatization" is expressed as follows,

They [Brahma, Vishnu, Shiva] exist through each other, and uphold each other; they are parts of one another; they subsist through one another; they are not for a moment separated; they never abandon one another.

The triad appears in Maitrayaniya Upanishad, for the first time in recognized roles known ever since, where they are deployed to present the concept of three Guṇa – the innate nature, tendencies and inner forces found within every being and everything, whose balance transform and keeps changing the individual and the world.[149][150] It is in the medieval Puranic texts, Trimurti concepts appears in various context, from rituals to spiritual concepts.[148] The Bhagavad Gita, in verses 9.18, 10.21-23 and 11.15, asserts that the triad or trinity is manifestation of one Brahman, which Krishna affirms himself to be.[151] However, suggests Bailey, the mythology of triad is "not the influence nor the most important one" in Hindu traditions, rather the ideologies and spiritual concepts develop on their own foundations.[149]

Avatars of Hindu deities

Hindu mythology has nurtured the concept of Avatar, which represents the descent of a deity on earth.[152][153] This concept is commonly translated as "incarnation",[152] and is an "appearance" or "manifestation".[154][155]

The concept of Avatar is most developed in Vaishnavism tradition, and associated with Vishnu, particularly with Rama and Krishna.[156][157] Vishnu takes numerous avatars in Hindu mythology. He becomes female, during the Samudra manthan, in the form of Mohini, to resolve a conflict between the Devas and Asuras. His male avatars include Matsya, Kurma, Varaha, Narasimha, Vamana, Parashurama, Rama, Krishna, Buddha, and Kalki.[157] Various texts, particularly the Bhagavad Gita, discuss the idea of Avatar of Vishnu appearing to restore the cosmic balance whenever the power of evil becomes excessive and causes persistent oppression in the world.[153]

In Shaktism traditions, the concept appears in its legends as the various manifestations of Devi, the Divine Mother principal in Hinduism.[158] The avatars of Devi or Parvati include Durga and Kali, who are particularly revered in eastern states of India, as well as Tantra traditions.[159][160][161] Twenty one avatars of Shiva are also described in Shaivism texts, but unlike Vaishnava traditions, Shaiva traditions have focussed directly on Shiva rather than the Avatar concept.[152]

Major regional and pan-Indian Hindu deities

| Name | Avatar or Associated with |

Geography | Image | Early surviving Art |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vishnu | Rama, Krishna, Narayana, Vithoba, Venkateswara, Jagannath, Gopal Varaha Naraenten (那羅延天, Japan) |

pan-Indian, Nepal, Sri Lanka |  |

2nd-century BCE |

| Shiva | Mahadeva, Pashupati, Tripurantaka, Viswanath Dakshinamurthy, Acalanatha Fudō Myōō (Japan)[162][163] |

pan-Indian, Nepal, Sri Lanka | |

1st-century BCE[164] |

| Brahma | Bonten (Japan)[165] Phra Phrom (Thailand) |

pan-Indian, Nepal, Sri Lanka |  |

6th-century CE |

| Ganesha | Ganapati, Vinayaka (son of Shiva, Parvati) Kangiten (Japan) |

pan-Indian, Nepal, Sri Lanka |  |

7th-century CE |

| Kartikeya | Skanda, Murugan (son of Shiva, Parvati) |

pan-India, Sri Lanka |  |

8th-century CE |

| Parvati | Uma, Devi, Gauri, Durga, Kali, Annapurna, Umahi (烏摩妃, Japan) Dewi Sri (Indonesia)[166] |

pan-Indian, Nepal, Sri Lanka |  |

5th-century CE |

| Lakshmi | Sri, Sita, Radha Kisshōten (Japan) Nang Kwak (Thailand)[167] |

pan-Indian, Nepal, Sri Lanka |  |

1st-century BCE |

| Saraswati | Benzaiten (Japan), Biàncáitiān (China), Thurathadi (Myanmar), Suratsawadi (Thailand)[168] |

pan-Indian, Nepal, Java, Bali, Sri Lanka |  |

11th-century CE |

| Durga | Parvati, Kali Betari Durga (Indonesia)[169] |

pan-Indian, Nepal, Sri Lanka |  |

8th-century CE |

| Kali | Durga, Parvati | pan-Indian, Nepal, Sri Lanka |  |

12th-century CE |

| Mariamman | Durga, Parvati | South India, Southeast Asia, Sri Lanka |

|

|

| Harihara | half Vishnu, half Shiva | pan-Indian, Sri Lanka | |

6th-century CE |

| Ardhanarishvara | half Shiva, half Parvati | pan-Indian, Nepal, Sri Lanka |  |

1st-century CE |

| Bhairava | Fierce manifestation of Shiva | pan-Indian, Nepal, Sri Lanka | |

See also

- Hindu denominations

- Hindu iconography

- Hindu mythology

- Puranas

- List of Hindu deities

- Rigvedic deities

Notes

- ↑ For translation of deva in singular noun form as "a deity, god", and in plural form as "the gods" or "the heavenly or shining ones", see: Monier-Williams 2001, p. 492 and Renou 1964, p. 55

- ↑ [a] Hark, Lisa; DeLisser, Horace (2011). Achieving Cultural Competency. John Wiley & Sons.

Three gods, Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiva, and other deities are considered manifestations of and are worshipped as incarnations of Brahman.

[b] Toropov & Buckles 2011: The members of various Hindu sects worship a dizzying number of specific deities and follow innumerable rites in honor of specific gods. Because this is Hinduism, however, its practitioners see the profusion of forms and practices as expressions of the same unchanging reality. The panoply of deities are understood by believers as symbols for a single transcendent reality.

[d] Orlando O. Espín, James B. Nickoloff (2007). An Introductory Dictionary of Theology and Religious Studies. Liturgical Press.While Hindus believe in many devas, many are monotheistic to the extent that they will recognise only one Supreme Being, a God or Goddess who is the source and ruler of the devas.

- ↑ The list of Vedic Devas somewhat varies across the manuscripts found in different parts of South Asia, particularly in terms of guides (Aswins) and personified Devas. One list based on Book 2 of Aitereya Brahmana is:[108][109]

- Devas personified: Indra (Śakra), Varuṇa, Mitra, Aryaman, Bhaga, Aṃśa, Vidhatr (Brahma),[110] Tvāṣṭṛ, Pūṣan, Vivasvat, Savitṛ (Dhatr), Vishnu.

- Devas as abstractions or inner principles: Ānanda (bliss, inner contentment), Vijñāna (knowledge), Manas (mind, thought), Prāṇa (life-force), Vāc (speech), Ātmā (soul, self within each person), and five manifestations of Rudra/Shiva – Īśāna, Tatpuruṣa, Aghora, Vāmadeva, Sadyojāta

- Devas as forces or principles of nature – Pṛthivī (earth), Agni (fire), Antarikṣa (atmosphere, space), Jal (water), Vāyu (wind), Dyauṣ (sky), Sūrya (sun), Nakṣatra (stars), Soma (moon)

- Devas as guide or creative energy – Vasatkara, Prajāpati

References

- ↑ Radhakrishnan and Moore (1967, Reprinted 1989), A Source Book in Indian Philosophy, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0691019581, pages 37-39, 401-403, 498-503

- 1 2 Mircea Eliade (2009), Yoga: Immortality and Freedom, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0691142036, pages 73-76

- 1 2 3 Nicholas Gier (2000), Spiritual Titanism: Indian, Chinese, and Western Perspectives, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0791445280, pages 59-76

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Jeaneane D Fowler (2012), The Bhagavad Gita, Sussex Academic Press, ISBN 978-1845193461, pages 253-262

- ↑ Renou 1964, p. 55

- ↑ Mike Burley (2012), Classical Samkhya and Yoga - An Indian Metaphysics of Experience, Routledge, ISBN 978-0415648875, page 39-41;

Lloyd Pflueger, Person Purity and Power in Yogasutra, in Theory and Practice of Yoga (Editor: Knut Jacobsen), Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120832329, pages 38-39;

Kovoor T. Behanan (2002), Yoga: Its Scientific Basis, Dover, ISBN 978-0486417929, pages 56-58 - 1 2 George Williams (2008), A Handbook of Hindu Mythology, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195332612, pages 90, 112

- ↑ Sanjukta Gupta (2013), Lakṣmī Tantra: A Pāñcarātra Text, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120817357, page 166

- ↑ Knut Jacobsen (2008), Theory and Practice of Yoga : 'Essays in Honour of Gerald James Larson, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120832329, pages 77-78

- ↑ David Leeming (2001), A Dictionary of Asian Mythology, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195120530, page 67

- ↑ Ellen Goldberg (2002), The Lord who is half woman: Ardhanārīśvara in Indian and feminist perspective, State University of New York Press, ISBN 0-791453251, pages 1-4

- ↑ TA Gopinatha Rao (1993), Elements of Hindu iconography, Vol 2, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120808775, pages 334-335

- ↑ Fred Kleiner (2012), Gardner's Art through the Ages: A Global History, Cengage, ISBN 978-0495915423, pages 443-444

- ↑ Cynthia Packert Atherton (1997), The Sculpture of Early Medieval Rajasthan, BRILL, ISBN 978-9004107892, pages 42-46

- ↑ Lance Nelson (2007), An Introductory Dictionary of Theology and Religious Studies (Editors: Orlando O. Espín, James B. Nickoloff), Liturgical Press, ISBN 978-0814658567, pages 562-563

- 1 2 3 Julius J. Lipner (2009), Hindus: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices, 2nd Edition, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-45677-7, pages 371-375

- 1 2 Frazier, Jessica (2011). The Continuum companion to Hindu studies. London: Continuum. pp. 1–15. ISBN 978-0-8264-9966-0.

- 1 2 For dualism school of Hinduism, see: Francis X. Clooney (2010), Hindu God, Christian God: How Reason Helps Break Down the Boundaries between Religions, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0199738724, pages 51-58, 111-115;

For monist school of Hinduism, see: B Martinez-Bedard (2006), Types of Causes in Aristotle and Sankara, Thesis - Department of Religious Studies (Advisors: Kathryn McClymond and Sandra Dwyer), Georgia State University, pages 18-35 - ↑ Michael Myers (2000), Brahman: A Comparative Theology, Routledge, ISBN 978-0700712571, pages 124-127

- 1 2 Thomas Padiyath (2014), The Metaphysics of Becoming, De Gruyter, ISBN 978-3110342550, pages 155-157

- 1 2 3 Klaus Klostermaier (2010), A Survey of Hinduism, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0791470824, pages 264-267

- 1 2 "pratima (Hinduism)". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 21 August 2011.

- ↑ PK Acharya, An Encyclopedia of Hindu Architecture, Oxford University Press, page 426

- ↑ VV Raman (2012), Hinduism and Science: Some Reflections, Zygon - Journal of Religion and Science, 47(3): 549–574, Quote (page 557): "Aside from nontheistic schools like the Samkhya, there have also been explicitly atheistic schools in the Hindu tradition. One virulently anti-supernatural system is/was the so-called Charvaka school."

- 1 2 John Clayton (2010), Religions, Reasons and Gods: Essays in Cross-cultural Philosophy of Religion, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0521126274, page 150

- ↑ A Goel (1984), Indian philosophy: Nyāya-Vaiśeṣika and modern science, Sterling, ISBN 978-0865902787, pages 149-151;

R Collins (2000), The sociology of philosophies, Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0674001879, page 836 - ↑ Naidoo, Thillayvel (1982). The Arya Samaj Movement in South Africa. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 158. ISBN 81-208-0769-3.

- ↑ Glyn Richards (1990), The World's Religions: The Religions of Asia (Editor: Friedhelm Hardy), Routledge, ISBN 978-0415058155, pages 173-176

- ↑ John E. Cort (1998), Open Boundaries: Jain Communities and Cultures in Indian History, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0791437865, pages 218-220

- 1 2 Hajime Nakamura (1998), A Comparative History of Ideas, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120810044, pages 26-33

- ↑ Ellen London (2008), Thailand Condensed: 2,000 Years of History & Culture, Marshall Cavendish, ISBN 978-9812615206, page 74

- ↑ Trudy Ring et al (1996), International Dictionary of Historic Places: Asia and Oceania, Routledge, ISBN 978-1884964046, page 692

- 1 2 Jean Holm and John Bowker (1998), Sacred Place, Bloomsbury Academic, ISBN 978-0826453037, pages 76-78

- ↑ Michael Coogan (2003), The Illustrated Guide to World Religions, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195219975, page 149

- ↑ Alain Daniélou (2001), The Hindu Temple: Deification of Eroticism, ISBN 978-0892818549, pages 82-83

- ↑ Patrick Olivelle (1992), The Samnyasa Upanisads, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195070453, pages 147-148 with footnotes 2 and 5

- ↑ Brodd, Jefferey (2003). World Religions. Winona, MN: Saint Mary's Press. ISBN 978-0-88489-725-5.

- ↑ Monier-Williams 1974, pp. 20–37

- 1 2 John Koller (2012), Routledge Companion to Philosophy of Religion (Editors: Chad Meister, Paul Copan), Routledge, ISBN 978-0415782944, pages 99-107

- 1 2 R Prasad (2009), A Historical-developmental Study of Classical Indian Philosophy of Morals, Concept Publishing, ISBN 978-8180695957, pages 345-347

- 1 2 Julius J. Lipner (2009), Hindus: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices, 2nd Edition, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-45677-7, page 8; Quote: "(...) one need not be religious in the minimal sense described to be accepted as a Hindu by Hindus, or describe oneself perfectly validly as Hindu. One may be polytheistic or monotheistic, monistic or pantheistic, even an agnostic, humanist or atheist, and still be considered a Hindu."

- ↑ Lester Kurtz (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Violence, Peace and Conflict, ISBN 978-0123695031, Academic Press, 2008

- ↑ MK Gandhi, The Essence of Hindu, Editor: VB Kher, Navajivan Publishing, see page 3; According to Gandhi, "a man may not believe in God and still call himself a Hindu."

- ↑ Monier Monier-Williams, A Sanskrit-English Dictionary" Etymologically and Philologically Arranged to cognate Indo-European Languages, Motilal Banarsidass, page 496

- ↑ John Stratton Hawley and Donna Marie Wulff (1998), Devi: Goddesses of India, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814912, page 2

- ↑ William K Mahony (1997), The Artful Universe: An Introduction to the Vedic Religious Imagination, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0791435809, page 18

- 1 2 Monier Monier-Williams, A Sanskrit-English Dictionary" Etymologically and Philologically Arranged to cognate Indo-European Languages, Motilal Banarsidass, page 492

- ↑ Deva Etymology Dictionary, Douglas Harper (2015)

- ↑ Wash Edward Hale (1999), Ásura in Early Vedic Religion, Motilal Barnarsidass, ISBN 978-8120800618, pages 5-11, 22, 99-102

- ↑ Monier Monier-Williams, A Sanskrit-English Dictionary" Etymologically and Philologically Arranged to cognate Indo-European Languages, Motilal Banarsidass, page 121

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica

- ↑ Don Handelman (2013), One God, Two Goddesses, Three Studies of South Indian Cosmology, Brill Academic, ISBN 978-9004256156, pages 23-29

- ↑ Wendy Doniger (1988), Textual Sources for the Study of Hinduism, Manchester University Press, ISBN 978-0719018664, page 67

- ↑ George Williams (2008), A Handbook of Hindu Mythology, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195332612, pages 24-33

- ↑ Bina Gupta (2011), An Introduction to Indian Philosophy, Routledge, ISBN 978-0415800037, pages 21-25

- ↑ Stella Kramrisch (1994), The Presence of Siva, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0691019307, pages 338-339

- ↑ M Chakravarti (1995), The concept of Rudra-Śiva through the ages, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120800533, pages 59-65

- ↑ David Kinsley (2005), Hindu Goddesses: Vision of the Divine Feminine in the Hindu Religious Traditions, University of California Press, ISBN 978-8120803947, pages 6-17, 55-64

- 1 2 David Kinsley (2005), Hindu Goddesses: Vision of the Divine Feminine in the Hindu Religious Traditions, University of California Press, ISBN 978-8120803947, pages 18, 19

- ↑ Christopher John Fuller (2004), The Camphor Flame: Popular Hinduism and Society in India, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0691120485, page 41

- ↑ Wash Edward Hale (1999), Ásura in Early Vedic Religion, Motilal Barnarsidass, ISBN 978-8120800618, page 20

- ↑ Ananda Coomaraswamy (1935), Angel and Titan: An Essay in Vedic Ontology, Journal of the American Oriental Society, volume 55, pages 373-374

- ↑ Ananda Coomaraswamy (1935), Angel and Titan: An Essay in Vedic Ontology, Journal of the American Oriental Society, volume 55, pages 373-418

- ↑ Nicholas Gier (1995), Hindu Titanism, Philosophy East and West, Volume 45, Number 1, pages 76, see also 73-96

- ↑ Ananda Coomaraswamy (1935), Angel and Titan: An Essay in Vedic Ontology, Journal of the American Oriental Society, volume 55, pages 373-374

- 1 2 Christopher K Chapple (2010), The Bhagavad Gita: Twenty-fifth–Anniversary Edition, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-1438428420, pages 610-629

- 1 2 Ludo Rocher (1986), The Puranas, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 978-3447025225, pages 1-5, 12-21

- ↑ Greg Bailey (2001), Encyclopedia of Asian Philosophy (Editor: Oliver Leaman), Routledge, ISBN 978-0415172813, pages 437-439

- ↑ Gregory Bailey (2003), The Study of Hinduism (Editor: Arvind Sharma), The University of South Carolina Press, ISBN 978-1570034497, page 139

- 1 2 Alain Daniélou (1991), The Myths and Gods of India, Princeton/Bollingen Paperbacks, ISBN 978-0892813544, pages 57-60

- 1 2 Jonathan Edelmann (2013), Hindu Theology as Churning the Latent, Journal of the American Academy of Religion, Volume 81, Issue 2, pages 439-441

- ↑ William K Mahony (1997), The Artful Universe: An Introduction to the Vedic Religious Imagination, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0791435809, pages 17, 27, 32

- 1 2 Nicholas Gier (1995), Hindu Titanism, Philosophy East and West, Volume 45, Number 1, pages 76-80

- 1 2 Stella Kramrisch and Raymond Burnier (1986), The Hindu Temple, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120802230, pages 75-78

- ↑ William K Mahony (1997), The Artful Universe: An Introduction to the Vedic Religious Imagination, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0791435809, pages 50, 72-73

- 1 2 Jonathan Edelmann (2013), Hindu Theology as Churning the Latent, Journal of the American Academy of Religion, Volume 81, Issue 2, pages 440-442

- ↑ Siroj Sorajjakool, Mark Carr and Julius Nam (2009), World Religions, Routledge, ISBN 978-0789038135, page 38

- 1 2 Monier Williams, Sanskrit-English dictionary, Izvara, Sanskrit Digital Lexicon, University of Cologne, Germany

- ↑ James Lochtefeld, "Ishvara", The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Vol. 1: A–M, Rosen Publishing. ISBN 0-8239-2287-1, page 306

- 1 2 Dale Riepe (1961, Reprinted 1996), Naturalistic Tradition in Indian Thought, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120812932, pages 177-184, 208-215

- 1 2 Ian Whicher, The Integrity of the Yoga Darsana, State University of New York press, ISBN 978-0791438152, pages 82-86

- ↑ G Oberhammer (1965), Zum problem des Gottesbeweises in der Indischen Philosophie, Numen, 12: 1-34

- ↑ Francis X. Clooney (2010), Hindu God, Christian God: How Reason Helps Break Down the Boundaries, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0199738724, pages 18-19, 35-39

- 1 2 Klaus Klostermaier (2007), A Survey of Hinduism, Third Edition, State University of New York, ISBN 978-0791470824, page 337

- ↑ A Goel (1984), Indian philosophy: Nyāya-Vaiśeṣika and modern science, Sterling, ISBN 978-0865902787, pages 149-151

- 1 2 FX Clooney (1997), What's a god? The quest for the right understanding of devatā in Brāhmaṅical ritual theory (Mīmāṃsā), International Journal of Hindu Studies, August 1997, Volume 1, Issue 2, pages 337-385

- ↑ P. Bilimoria (2001), Hindu doubts about God: Towards Mimamsa Deconstruction, in Philosophy of Religion: Indian Philosophy (Editor: Roy Perrett), Volume 4, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-8153-3611-2, pages 87-106

- ↑ A Malinar (2014), Current Approaches: Articles on Key Themes, in The Bloomsbury Companion to Hindu Studies (Editor: Jessica Frazier), Bloomsbury Academic, ISBN 978-1472511515, page 79

- 1 2 Lloyd Pflueger, Person Purity and Power in Yogasutra, in Theory and Practice of Yoga (Editor: Knut Jacobsen), Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120832329, pages 38-39

- ↑ Mike Burley (2012), Classical Samkhya and Yoga - An Indian Metaphysics of Experience, Routledge, ISBN 978-0415648875, page 39

- ↑ Richard Garbe (2013), Die Samkhya-Philosophie, Indische Philosophie Volume 11, ISBN 978-1484030615, pages 25-27 (in German)

- ↑ Knut Jacobsen (2008), Theory and Practice of Yoga : 'Essays in Honour of Gerald James Larson, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120832329, pages 15-16

- ↑ Knut Jacobsen (2008), Theory and Practice of Yoga : 'Essays in Honour of Gerald James Larson, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120832329, pages 76-77

- ↑ Orlando Espín and James Nickoloff (2007), An Introductory Dictionary of Theology and Religious Studies, Liturgical Press, ISBN 978-0814658567, page 651

- ↑ Ian Whicher (1999), The Integrity of the Yoga Darsana: A Reconsideration of Classical Yoga, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0791438152, page 86

- ↑ Knut Jacobsen (2008), Theory and Practice of Yoga : 'Essays in Honour of Gerald James Larson, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120832329, page 77

- ↑ JN Mohanty (2001), Explorations in Philosophy, Vol 1 (Editor: Bina Gupta), Oxford University Press, page 107-108

- ↑ Paul Hacker (1978), Eigentumlichkeiten dr Lehre und Terminologie Sankara: Avidya, Namarupa, Maya, Isvara, in Kleine Schriften (Editor: L. Schmithausen), Franz Steiner Verlag, Weisbaden, pages 101-109 (in German), also pages 69-99

- 1 2 William Indich (2000), Consciousness in Advaita Vedanta, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120812512, page 5

- ↑ William James (1985), The Varieties of Religious Experience, Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0674932258, page 404 with footnote 28

- ↑ Lance Nelson (1996), Living liberation in Shankara and classical Advaita, in Living Liberation in Hindu Thought (Editors: Andrew O. Fort, Patricia Y. Mumme), State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0791427064, pages 38-39, 59 (footnote 105)

- ↑ Anantanand Rambachan (2012), Advaita Worldview, The: God, World, and Humanity, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0791468524, pages 1-2

- ↑ Alain Daniélou (1991), The Myths and Gods of India, Princeton/Bollingen Paperbacks, ISBN 978-0892813544, pages 350-354

- ↑ Serenity Young (2001), Hinduism, Marshall Cavendish, ISBN 978-0761421160, page 73

- ↑ David R Kinsley (1995), Tantric Visions of the Divine Feminine: The Ten Mahāvidyās, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120800533, pages 136-140, 122-128

- ↑ RT Vyas and Umakant Shah, Studies in Jaina Art and Iconography and Allied Subjects, Abhinav, ISBN 978-8170173168, pages 23-26

- ↑ WJ Wilkins (2003), Hindu Gods and Goddesses, Dover, ISBN 978-0486431567, pages 9-10

- ↑ Hermann Oldenberg (1988), The Religion of the Veda, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120803923, pages 23-50

- ↑ AA MacDonell, Vedic mythology, p. PA19, at Google Books, Oxford University Press, pages 19-21

- ↑ Francis X Clooney (2010), Divine Mother, Blessed Mother, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0199738731, page 242

- ↑ See White Yajurveda verses 20.11 and 20.36, for example: Ralph Griffith, The texts of the white Yajurveda EJ Lazarus, pages 187, also 190, 132-135, 241

- 1 2 3 Lynn Foulston, Stuart Abbott (2009). Hindu goddesses: beliefs and practices. Sussex Academic Press. pp. 1–3, 40–41. ISBN 9781902210438.

- 1 2 3 4 David Lawrence (2012), The Routledge Companion to Theism (Editors: Charles Taliaferro, Victoria S. Harrison and Stewart Goetz), Routledge, ISBN 978-0415881647, pages 78-79

- 1 2 Jeffrey Brodd (2003), World Religions: A Voyage of Discovery, Saint Mary's Press, ISBN 978-0884897255, page 43

- ↑ Christopher John Fuller (2004), The Camphor Flame: Popular Hinduism and Society in India, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0691120485, pages 30-31, Quote: "Crucial in Hindu polytheism is the relationship between the deities and humanity. Unlike Jewish, Christian and Islamic monotheism, predicated on the otherness of God and either his total separation from man and his singular incarnation, Hinduism postulates no absolute distinction between deities and human beings. The idea that all deities are truly one is, moreover, easily extended to proclaim that all human beings are in reality also forms of one supreme deity - Brahman, the Absolute of philosophical Hinduism. In practice, this abstract monist doctrine rarely belongs to an ordinary Hindu's statements, but examples of permeability between the divine and human can be easily found in popular Hinduism in many unremarkable contexts".

- ↑ Abanindranth Tagore, Some notes on Indian Artistic Anatomy, pages 1-21

- ↑ Stella Kramrisch (1958), Traditions of the Indian Craftsman, The Journal of American Folklore, Vol. 71, No. 281, pages 224-230

- ↑ John Cort (2011), Jains in the World, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0199796649, pages 20-21, 56-58

- ↑ Brihat Samhita of Varaha Mihira, PVS Sastri and VMR Bhat (Translators), Reprinted by Motilal Banarsidass (ISBN 978-8120810600), page 520

- ↑ Sanskrit: (Source), pages 142-143 (note that the verse number in this version is 58.10-11)

- 1 2 3 4 5 Jeaneane D Fowler (1996), Hinduism: Beliefs and Practices, Sussex Academic Press, ISBN 978-1898723608, pages 41-45

- ↑ Gopinath Rao, Elements of Hindu Iconography Madras, Cornell University Archives, pages 17-39

- ↑ Stella Kramrisch (1994), The Presence of Siva, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0691019307, pages 179-187

- ↑ Michael Willis (2009), The Archaeology of Hindu Ritual, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0521518741, pages 96-112, 123-143, 168-172

- ↑ Heather Elgood (2000), Hinduism and the Religious Arts, Bloomsbury Academic, ISBN 978-0304707393, pages 14-15, 32-36

- ↑ Harold Coward and David Goa (2008), Mantra : 'Hearing the Divine In India and America, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120832619, pages 25-30

- ↑ James Lochtefeld (2002), The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism: A-M, The Rosen Publishing Group, ISBN 978-0-8239-3180-4, page 726

- ↑ Stella Kramrisch (1994), The Presence of Siva, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0691019307, pages 243-249

- ↑ Scott Littleton (2005), Gods, Goddesses, And Mythology, Volume 11, Marshall Cavendish, ISBN 978-0761475590, page 1125

- ↑ Mukul Goel (2008), Devotional Hinduism: Creating Impressions for God, iUniverse, ISBN 978-0595505241, page 77

- 1 2 James Lochtefeld (2002), Puja in The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Volume 2, Rosen Publishing, ISBN 0-823922871, pages 529–530

- ↑ Flood, Gavin D. (2002). The Blackwell Companion to Hinduism. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 6–7. ISBN 978-0-631-21535-6.

- ↑ Paul Courtright (1985), in Gods of Flesh/Gods of Stone (Joanne Punzo Waghorne, Norman Cutler, and Vasudha Narayanan, eds), ISBN 978-0231107778, Columbia University Press, see Chapter 2

- ↑ Lindsay Jones, ed. (2005). Gale Encyclopedia of Religion. 11. Thompson Gale. pp. 7493–7495. ISBN 0-02-865980-5.

- ↑ Willis, Michael D. (2009). "2: 6". The Archaeology of Hindu Ritual. Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Willis, Michael D. (2008). The Formation of Temple Ritual in the Gupta Period: pūjā and pañcamahāyajña. Gerd Mevissen.

- ↑ Puja, Encyclopædia Britannica (2011)

- ↑ Hiro G. Badlani (2008), Hinduism: A path of ancient wisdom, ISBN 978-0595436361, pages 315-318

- ↑ Paul Thieme (1984), "Indische Wörter und Sitten," in Kleine Schriften, Vol. 2, pages 343–370

- ↑ Fuller, C. J. (2004), The Camphor Flame: Popular Hinduism and Society in India, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, pp. 66–73, 308, ISBN 978-069112048-5

- ↑ Diana L. Eck (2008), Darśan: Seeing the Divine Image in India, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120832664, pages 47-49

- ↑ Diana L. Eck (2008), Darśan: Seeing the Divine Image in India, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120832664, pages 45-46

- ↑ Jonathan Lee and Kathleen Nadeau (2010), Encyclopedia of Asian American Folklore and Folklife, Volume 1, ABC, ISBN 978-0313350665, pages 480-481

- ↑ Jean Holm and John Bowker (1998), Worship, Bloomsbury Academic, ISBN 978-1855671119, page 83, Quote: "Temples are the permanent residence of a deity and daily worship is performed by the priest, but the majority of Hindus visit temples only on special occasions. Worship in temples is wholly optional for them".

- ↑ Guy Beck (2005), Alternative Krishnas: Regional and Vernacular Variations on a Hindu Deity, SUNY Press, ISBN 978-0791464151, pages 1-2

- ↑ Editors of Hinduism Today, Editors of Hinduism Today. "What is Hinduism?". Himalayan Academy Publications. Retrieved 16 October 2011.

- ↑ Andrew J Nicholson (2013), Unifying Hinduism: Philosophy and Identity in Indian Intellectual History, Columbia University Press, ISBN 978-0231149877, pages 167-168

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Jan Gonda (1969), The Hindu Trinity, Anthropos, 63/64, 1/2, pages 212-226

- 1 2 3 GM Bailey (1979), Trifunctional Elements in the Mythology of the Hindu Trimūrti, Numen, Vol. 26, Fasc. 2, pages 152-163

- ↑ James G. Lochtefeld, Guna, in The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism: A-M, Vol. 1, Rosen Publishing, ISBN 9780823931798, page 265

- ↑ Rudolf V D'Souza (1996), The Bhagavadgītā and St. John of the Cross, Gregorian University, ISBN 978-8876526992, pages 340-342

- 1 2 3 James Lochtefeld (2002), The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism: A-M, The Rosen Publishing Group, ISBN 978-0-8239-3180-4, pages 72-73

- 1 2 Sheth, Noel (Jan 2002). "Hindu Avatāra and Christian Incarnation: A Comparison". Philosophy East and West. University of Hawai'i Press. 52 (1 (Jan. 2002)): 98–125. JSTOR 1400135. doi:10.1353/pew.2002.0005.

- ↑ Matchett, Freda (2001). Krishna, Lord or Avatara?: the relationship between Krishna and Vishnu. 9780700712816. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-7007-1281-6.

- ↑ Christopher Hugh Partridge, Introduction to World Religions, pg. 148

- ↑ Kinsley, David (2005). Lindsay Jones, ed. Gale's Encyclopedia of Religion. 2 (Second ed.). Thomson Gale. pp. 707–708. ISBN 0-02-865735-7.

- 1 2 Bryant, Edwin Francis (2007). Krishna: A Sourcebook. Oxford University Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-19-514891-6.

- ↑ Hawley, John Stratton; Vasudha Narayanan (2006). The life of Hinduism. University of California Press. p. 174. ISBN 978-0-520-24914-1.

- ↑ David Kinsley (1988), Hindu Goddesses: Vision of the Divine Feminine in the Hindu Religious Traditions, University of California Press, ISBN 0-520063392, pages 45-48, 96-97

- ↑ Sally Kempton (2013), Awakening Shakti: The Transformative Power of the Goddesses of Yoga, ISBN 978-1604078916, pages 165-167

- ↑ Eva Rudy Jansen, The Book of Hindu Imagery: Gods, Manifestations and Their Meaning, Holland: Binkey Kok, ISBN 978-9074597074, pages 133-134, 41

- ↑ Miyeko Murase (1975), Japanese Art: Selections from the Mary and Jackson Burke Collection, The Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York), ISBN 978-0870991363, page 31

- ↑ Jiro Takei and Marc P Keane (2001), SAKUTEIKI, Tuttle, ISBN 978-0804832946, page 101

- ↑ M Chakravarti (1995), The concept of Rudra-Śiva through the ages, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120800533, pages 148-149

- ↑ Robert Paine and Alexander Soper (1992), The Art and Architecture of Japan, Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0300053333, page 60

- ↑ Joe Cribb (1999), Magic Coins of Java, Bali and the Malay Peninsula, British Museum Press, ISBN 978-0714108810, page 77

- ↑ Jonathan Lee, Fumitaka Matsuoka et al (2015), Asian American Religious Cultures, ABC, ISBN 978-1598843309, page 892

- ↑ Kinsley, David (1988), Hindu Goddesses: Vision of the Divine Feminine in the Hindu Religious Traditions, University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-06339-2, pages 94-97

- ↑ Francine Brinkgreve (1997), Offerings to Durga and Pretiwi in Bali, Asian Folklore Studies Vol. 56, No. 2, pages 227-251

Sources

- Daniélou, Alain (1991) [1964]. The myths and gods of India. Inner Traditions, Vermont, USA. ISBN 0-89281-354-7.

- Fuller, C. J. (2004). The Camphor Flame: Popular Hinduism and Society in India. Princeton University Press, New Jersey. ISBN 0-691-12048-X.

- Harman, William, "Hindu Devotion". In: Contemporary Hinduism: Ritual, Culture, and Practice, Robin Rinehard, ed. (2004) ISBN 1-57607-905-8.

- Kashyap, R.L. Essentials of Krishna and Shukla Yajurveda; SAKSI, Bangalore, Karnataka ISBN 81-7994-032-2.

- Keay, John (2000). India, a History. New York, United States: Harper Collins Publishers. ISBN 0-00-638784-5.

- Pattanaik, Devdutt (2009). 7 Secrets from Hindu Calendar Art. Westland, India. ISBN 978-81-89975-67-8.

- Monier-Williams, Monier (1974), Brahmanism and Hinduism: Or, Religious Thought and Life in India, as Based on the Veda and Other Sacred Books of the Hindus, Elibron Classics, Adamant Media Corporation, ISBN 1-4212-6531-1, retrieved 8 July 2007

- Monier-Williams, Monier (2001) [first published 1872], English Sanskrit dictionary, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 81-206-1509-3, retrieved 24 July 2007

- Renou, Louis (1964), The Nature of Hinduism, Walker

- Toropov, Brandon; Buckles, Luke (2011), Guide to World Religions, Penguin

- Swami Bhaskarananda, (1994). Essentials of Hinduism. (Viveka Press) ISBN 1-884852-02-5.

- Vastu-Silpa Kosha, Encyclopedia of Hindu Temple architecture and Vastu. S.K.Ramachandara Rao, Delhi, Devine Books, (Lala Murari Lal Chharia Oriental series) ISBN 978-93-81218-51-8 (Set)

- Werner, Karel A Popular Dictionary of Hinduism. (Curzon Press 1994) ISBN 0-7007-0279-2.

Further reading

- Chandra, Suresh (1998). Encyclopaedia of Hindu Gods and Goddesses. Sarup & Sons, New Delhi, India. ISBN 81-7625-039-2.

- Pattanaik, Devdutt (2003). Indian mythology: tales, symbols, and rituals from the heart of the Subcontinent. Inner Traditions / Bear & Company. ISBN 0-89281-870-0.

- Kinsley, David. Hindu Goddesses: Vision of the Divine Feminine in the Hindu Religious Traditions. Motilal Banarsidass, New Delhi, India. ISBN 81-208-0379-5.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hindu deities. |

- A chart of the main Hindu deities (with pictures)

_proportions_posture_shape_design_05.jpg)

_proportions_posture_shape_design_06.jpg)

_proportions_posture_shape_design_10.jpg)

_(5153565239).jpg)