Hill 262

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Hill 262, or the Mont Ormel ridge (elevation 262 metres (860 ft)), is an area of high ground above the village of Coudehard in Normandy that was the location of a bloody engagement in the final stages of the Normandy Campaign during the Second World War. By late summer 1944, the bulk of two German armies had become surrounded by the Allies near the town of Falaise. The Mont Ormel ridge, with its commanding view of the area, sat astride the Germans' only escape route. Polish forces seized the ridge's northern height on 19 August and, despite being isolated and coming under sustained attack, held it until noon on 21 August, contributing greatly to the decisive Allied victory that followed.

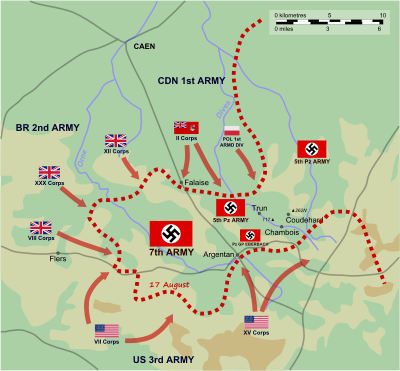

The American success of Operation Cobra provided the Allies with an opportunity to cut off and destroy most German forces west of the River Seine. American, British and Canadian armies converged on the area around Falaise, trapping the German Seventh Army and elements of the Fifth Panzer Army in what became known as the "Falaise pocket". On 20 August Generalfeldmarschall Walter Model ordered a withdrawal, but by this time the Allies were already blocking his path. During the night of 19 August, two battlegroups of Stanisław Maczek's Polish 1st Armoured Division had established themselves in the mouth of the Falaise pocket on and around the northernmost of the Mont Ormel ridge's two peaks.

On 20 August, with his forces encircled, Model organised attacks on the Polish position from both within and outside the pocket. The Germans managed to isolate the ridge and force open a narrow escape corridor. Lacking the fighting power to close the corridor, the Poles nevertheless directed constant and accurate artillery fire on German units retreating from the pocket, causing heavy casualties. Exasperated, the Germans launched fierce attacks throughout 20 August which inflicted losses on Hill 262's entrenched defenders. Exhausted and dangerously low on ammunition, the Poles managed to retain their foothold on the ridge. The following day, less intense attacks continued until midday, when the last German effort to overrun the position was defeated at close quarters. The Poles were relieved by the Canadian Grenadier Guards shortly after noon; their dogged stand had ensured the closure of the Falaise pocket and the collapse of the German position in Normandy.

Background

On 25 July 1944, Lieutenant General Omar Bradley launched Operation Cobra against the German defences penning his First United States Army into its Normandy beachhead.[8] Although intended only to cut a corridor through to Brittany thereby freeing his forces of the constraints of operating in the bocage,[9] the offensive precipitated a general collapse of the German position opposite the American sector when Generalfeldmarschall Günther von Kluge's Army Group B was slow to withdraw and expended many of its remaining combat-effective formations in futile counterattacks.[10] With the German left flank in ruins the Americans began a headlong advance into Brittany, but a large concentration of German forces—including most of their armoured strength—remained opposite the British and Canadian sector. Sensing the opportunity to encircle these forces and inflict a decisive defeat and with Bradley's urging, the Allied ground forces commander General Bernard Montgomery sanctioned General George Patton's United States Third Army to swing north towards the town of Falaise.[11] Its capture would cut off virtually all the remaining German forces in Normandy.[12] While the Americans pressed in from the south and the British Second Army from the west, the task of completing the encirclement fell to the newly inaugurated First Canadian Army under General Harry Crerar. To accomplish this, Crerar and Lieutenant-General Guy Simonds, of II Canadian Corps, planned an Anglo-Canadian offensive code-named Operation Totalize.[13] Intended to seize an area of high ground north of Falaise, by 9 August the offensive was in trouble despite initial gains on Verrières Ridge and near Cintheaux.[14] Strong German defences and indecision and hesitation in the Canadian chain of command hampered Allied efforts,[15] and the 4th Canadian and 1st Polish Armoured Divisions suffered heavy casualties.[16] Anglo-Canadian forces reached Hill 195 north of Falaise on 10 August but were unable to make further progress, so Totalize was called off.[16]

The Canadians reorganised and on 14 August they launched Operation Tractable; three days later Falaise fell.[18] The Allied noose was relentlessly closing around von Kluge's force, and it fell to the 1st Polish Armoured Division to draw it tight.[19] In a meeting with his divisional commanders on 19 August, Simonds emphasised the importance of quickly closing the Falaise Pocket to General Stanisław Maczek. Assigned responsibility for the Moissy–Chambois–Coudehard area,[20] Maczek's 1st Polish Armoured Division had split into three battlegroups[nb 3]—each of an armoured regiment and an infantry battalion—and were sweeping the countryside north of Chambois.[22] However, facing stiff German resistance and with Koszutski's battlegroup having "gone astray" and needing to be rescued,[nb 4] the division had not yet taken Chambois, Coudehard, or the Mont Ormel ridge.[24] Galvanised by Simonds, Maczek was determined to get his men onto their objectives as soon as possible.[25] The 10th Dragoons (10th Polish Motorised infantry Battalion) and 10th Polish Mounted Rifle Regiment (the division's armoured reconnaissance regiment) drove hard on Chambois,[26] the capture of which would effect a link-up with the United States 90th Infantry Division who were simultaneously attacking the town from the south.[26][27] Having taken Trun and Champeaux the 4th Canadian Armoured Division was able to assist, and by the evening of 19 August the town was in Allied hands.[nb 5][28]

Although the arms of the encirclement had now made contact, the Allies were not yet astride Seventh Army's escape route in any great strength and their positions came under frenzied assault.[28][29] During the day an armoured column from the 2nd Panzer Division broke through the Canadians in St. Lambert, capturing half the village and maintaining an open road for six hours until being forced out.[30] Many Germans escaped along this route and numerous small parties infiltrated on foot through to the River Dives during the night.[31]

Mont Ormel ridge

Northeast of Chambois and overlooking the Dives River valley, an elongated, wooded ridge runs roughly north–south above the village of Coudehard.[16][32] The ridge's two highest peaks—Points 262 North (262N) and 262 South (262S)—lie either side of a pass within which the hamlet of Mont Ormel, from which the ridge takes its name, is situated.[nb 6] One of the few westbound roads in the area runs from Chambois through the pass, heading towards Vimoutiers and the River Seine.[32][34] Historian Michael Reynolds describes Point 262N as offering "spectacular views over much of the Falaise Pocket".[33] Viewing the feature on an Allied map, Maczek commented that it resembled a caveman's club with two bulbous heads; the Poles nicknamed it the Maczuga, Polish for "mace".[34][35] The ridge, known to the Allies as Hill 262,[5] formed a crucial blocking position for sealing the Falaise Pocket and preventing any outside attempts to relieve the German Seventh Army.[16]

19 August

Shortly after noon on 19 August, Lieutenant-Colonel Zgorzelski's battlegroup (the 1st Armoured Regiment, 9th Infantry Battalion, and a company of anti-tank guns) made a thrust towards Coudehard and the Mont Ormel ridge.[33] While part of the battlegroup remained in Coudehard, two companies of the Polish Highland (Podhalian) Battalion led the assault up the north peak, followed by the squadrons of Lieutenant-Colonel Aleksander Stefanowicz's 1st Armoured Regiment who picked their way up the ridge's only vehicular access—a narrow, winding track.[32][36] The Poles reached the summit at approximately 12:40 and took captive a number of demoralised Germans before proceeding to shell a 2--mile long column of PzKpfw V Panther tanks, armored cars, 88 mm and 105 mm artillery pieces, nebelwerfers, trucks and many horse-drawn carts. Three companies of the Polish 1. Armored Regiment opened fire from every heavy machine gun and cannon. The lead vehicles were quickly destroyed and the Panthers because of bad position could not hit the Shermans at the top of the hill (the shells were passing just above the turrets of the Shermans)[17]. Because of the total destruction of the equipment and the few POWs taken, the Poles called the remnants of the column that approached them through the pass along the Chambois–Vimoutiers road: "Psie Pole." [32][37] The victory was hard won over a period of a few hours: the Germans, despite being "shocked" to discover that Point 262N was now in Polish hands,[32] quickly responded with a bombardment from rocket-launchers and anti-tank guns. The Poles counterattacked and more Germans, including wounded, were taken prisoner.[38] These were moved to a hunting lodge (the Zameczek) on the ridge's northern slope.[39] Point 137, near Coudehard, fell just after 15:30, yielding further captives.[nb 7][25]

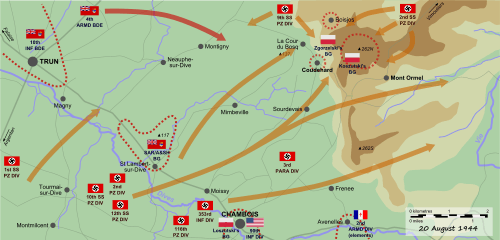

At around 17:00 Lieutenant-Colonel Koszutski's battlegroup, consisting of the 2nd Armoured Regiment and the 8th Infantry Battalion, arrived at the ridge, followed by the rest of the Polish Highland Battalion and elements of the 9th Infantry Battalion at 19:30.[39] The remainder of the 9th Infantry Battalion and the anti-tank company had remained around Boisjos 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) north of Coudehard, but the bulk of two battlegroups—some 80 tanks, 20 anti-tank guns, and around 1,500 infantrymen[3]—was now concentrated on and around Point 262N. The Poles did not, however, occupy Point 262S.[40] Although Lieutenant-Colonel Zdzisław Szydłowski, commanding the 9th Infantry Battalion, was given orders to take the southern peak, with darkness falling and thick smoke from the burning German column in the pass obscuring the battlefield this was deemed too hazardous to attempt before next light.[41] The Poles spent the night fortifying Point 262N and entrenching the southern, southwestern, and northeastern approaches to their positions.[33][42]

20 August

Of the approximately 20 German infantry and armoured divisions trapped in the Falaise pocket around 12 were still operating with a degree of combat-effectiveness.[nb 8] As these formations retreated eastwards they fought desperately to keep the jaws of the encirclement—formed by the Canadians in Trun and St. Lambert, and the Poles and Americans in Chambois—from closing. German movement out of the pocket throughout the night of 19 August cut off the Polish battlegroups on the Mont Ormel ridge.[34] On discovering this Stefanowicz conferred with Koszutski. Lacking sufficient means to either seal the pocket or fight their way clear, the two decided that the only chance of survival for their force was to hold fast until relieved.[39] Although the Polish soldiers on Point 262N could hear movement from the valley below, other than some mortar rounds that landed among the positions of the 8th Infantry Battalion the night passed uneventfully.[41] Without possession of Point 262S the Poles were unable to interfere with the large numbers of German troops slipping past the southern slopes of the ridge.[43] The uneven, wooded terrain, interspersed with thick hedgerows, made control of the ground to the west and southwest difficult by day and impossible by night.[40] As it grew light on 20 August Szydłowski prepared to fulfil his orders of the previous day and organised two companies of his 9th Infantry Battalion, supported by the 1st Armoured Regiment, for an attack across the road towards Point 262S. However, hampered by the wreckage littering the pass the attack soon bogged down in the face of fierce German resistance.[41]

The Poles' possession of around 2 square kilometres (0.77 sq mi) of commanding terrain overlooking the Seventh Army's only route out of Normandy was a serious impediment to the German retreat.[43] Field Marshal Walther Model, who on succeeding von Kluge two days earlier had authorised a general withdrawal,[4] was well aware of the need to remove the "cork"[39] from the bottle containing the Seventh Army. He ordered elements of the 2nd SS Panzer Division Das Reich and the 9th SS Panzer Division Hohenstaufen—located outside the pocket—to attack Hill 262.[27][28] At 09:00 the 8th Infantry Battalion's positions around the Zameczek to the north and northeast of point 262N were assaulted, and it was not until 10:30 that the Germans were driven back. In the heavy fighting a number of the 1st Armoured Regiment's supply lorries were destroyed.[44]

From within the pocket, German formations seeking an escape route were filtering through gaps in the Allied lines between Trun and Chambois,[nb 9] heading towards the ridge from the west. The Poles could see the road from Chambois choked with troops and vehicles attempting to pass along the Dives valley.[39] A number of columns moving down from the northeast that included tanks and self-propelled artillery were subjected to an hour-long bombardment from the 1st Armoured Regiment's 3rd Squadron, breaking them up and scattering their infantry.[44]

Having spotted German tank movements towards a nearby height, Point 239 (roughly 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) north of the ridge[6]), an attack was planned to take this feature and provide a buffer for the Poles' northern positions around the Zameczek. However, the 2nd Armoured Regiment's 2nd Squadron, tasked with capturing Point 239, was unable to release its tanks from their defensive duties.[44] At one point during the day[nb 10] a Panther tank of the 2nd SS Panzer Division worked its way onto the height and, at a range of 1,400 metres (1,500 yd), picked off five Shermans of the 1st Armoured Regiment's 3rd Squadron.[3][45][46] The survivors were forced to change position although they later lost another tank to fire from the north.[45]

Around midday the Germans opened up an artillery and mortar barrage that caused casualties among the ridge's defenders and lasted for the entire afternoon.[45] At about the same time, Kampfgruppe Weidinger seized an important road junction northeast of Coudehard.[3] Several units of the 10th SS, 12th SS, and 116th Panzer Divisions managed to clear a corridor past Point 262N, and by mid afternoon about 10,000 German troops had passed out of the pocket.[47]

A battalion of the 3rd Parachute Division, along with an armoured regiment of the 1st SS Panzer Division, now joined the assault on the ridge.[47] At 14:00 the 8th Infantry Battalion on the ridge's northern slopes once more came under attack. Although the infantry and armour closing in on the Polish positions were eventually repulsed, with a large number of prisoners being taken and artillery again causing significant casualties,[45][47] the Poles were being gradually pushed back.[48] However, they managed to retain their grip on Point 262N and with well-coordinated artillery fire continued to exact a toll on German units traversing the corridor.[48] Another attempt was made to organise an attack towards Point 239 but the Germans were ready and the 9th Infantry Battalion's 3rd Company was driven back with heavy losses.[49]

Exasperated by the casualties to his men, Seventh Army commander Oberstgruppenführer Paul Hausser ordered the Polish positions to be "eliminated".[47] At 15:00,[49] substantial forces, including remnants of the 352nd Infantry Division and several battle groups from the 2nd SS Panzer Division, inflicted heavy casualties on the 8th and 9th Infantry Battalions.[48] By 17:00 the attack was at its height and the Poles were contending with German tanks and infantry inside their perimeter.[49] Grenadiers of the 2nd SS Panzer Division very nearly reached the ridge's summit before being repulsed by the well dug in Polish defenders.[50] The integrity of the position was not restored until 19:00,[51] by which time the Poles had expended almost all their ammunition leaving themselves in a precarious situation.[48] A 20-minute ceasefire was arranged to allow the Germans to evacuate a large medical convoy, after which fighting resumed with redoubled intensity.[52]

Earlier in the day, Simonds had ordered his troops to "make every effort" to reach the Poles isolated on Hill 262,[53] but at "sacrificial" cost the remnants of the 9th SS Panzer and 3rd Parachute Divisions had succeeded in preventing the Canadians from intervening.[11][54] Dangerously low on supplies and unable to evacuate their prisoners or the wounded of both sides—many of whom received further injuries from the unremitting hail of mortar bombs—the Poles had hoped to see the Canadian 4th Armoured Division coming to their rescue by evening. However, as night fell it became clear that no Allied relief force would reach the ridge that day.[55] Lacking the means to interfere, the exhausted Poles were forced to watch as the remnants of the XLVII Panzer Corps left the pocket. Fighting died down and was sporadic throughout the hours of darkness; after the brutality of the day's combat both sides avoided contact although frequent Polish artillery strikes continued to harass German forces retreating from the sector.[48] Stefanowicz, himself wounded during the day's fighting,[52] struck a fatalistic note as he addressed his four remaining officers:

Gentlemen, all is lost. I do not think that the Canadians can come to our rescue. We have only about 110 able-bodied men left. Five shells per gun and 50 bullets per man. That's very little, but fight all the same. Surrender to the S.S. is futile; you know that. I thank you. You have fought well. Good luck, gentlemen. Tonight we shall die for Poland and for civilization! . . . each tank will fight independently, and eventually each man for himself."[56]

21 August

The next morning, despite poor flying weather, an effort was made to air-drop ammunition to the Polish force on the ridge.[57] Learning that the Canadians had resumed their push and were making for Point 239, at 07:00 a platoon of the 1st Armoured Regiment's 3rd Squadron reconnoitered the German positions below the Zameczek.[49]

Further German attacks were launched during the morning, both from inside the pocket along the Chambois–Vimoutiers road, and from the east. Raids from the direction of Coudehard managed to penetrate the Polish defences and take captives. The final German effort came at around 11:00—SS remnants had infiltrated through the wooded hills to the rear of the 1st Armoured Regiment's dressing station. This "suicidal" assault was defeated at point-blank range by the 9th Infantry Battalion with the 1st Armoured Regiment's tanks using their anti-aircraft machine guns in support.[6][58] The machine guns' tracer ammunition set fire to the grass, killing wounded men on the slope.[59] As the final infantry assaults melted away, the German artillery and mortar fire targeting the hill subsided as well.[59]

Moving up from Chambois, the Polish 1st Armoured Division's reconnaissance regiment made an attempt to reach their comrades on Point 262N but was mistakenly fired upon by the ridge's defenders. The regiment withdrew after losing two Cromwell tanks.[7] At 12:00 a Polish forward patrol from the ridge encountered the Canadian vanguard near Point 239.[6] The Canadian Grenadier Guards reached the ridge just over an hour later, having fought for more than five hours and accounted for two Panthers, a Panzer IV, and two self-propelled guns along their route.[7] By 14:00, with the arrival of the first supply convoy, the position was relieved.[6]

Aftermath

The Falaise pocket was considered closed by the evening of 21 August.[60] Tanks of the Canadian 4th Armoured Division had linked up with the Polish forces in Coudehard, and the Canadian 3rd and 4th Infantry Divisions had fully secured St. Lambert and the northern passage to Chambois.[60]

Both Reynolds and McGilvray place the Polish losses on the Maczuga at 351 killed and wounded and 11 tanks lost,[6][7] although Jarymowycz gives higher figures of 325 killed, 1,002 wounded, and 114 missing—approximately 20% of the division's combat strength.[54] For the entire operation to close the Falaise pocket, Copp quotes from the 1st Polish Armoured Division's operational report, citing 1,441 casualties including 466 killed in action.[61] McGilvray estimates the German losses in their assaults on the ridge as around 500 dead with a further 1,000 taken prisoner, most of these from the 12th SS Panzer Division. He also records "scores" of Tiger, Panther and Panzer IV tanks destroyed, as well as a significant quantity of artillery pieces.[6]

Although some estimates state that up to 100,000 German troops, many of them wounded, may have succeeded in escaping the Allied encirclement, they left behind 40,000-50,000 prisoners and over 10,000 dead.[1] According to military historian Gregor Dallas: "The Poles had closed the Falaise Pocket. The Poles had opened the gate to Paris."[62] Simonds stated that he had "never seen such wholesale havoc in his life" and Canadian engineers erected a sign on Point 262N's summit reading simply "A Polish Battlefield".[6]

In 1965 on the battle's 20th anniversary, a monument to the Polish, Canadian, American and French units that took part in the battle was erected on Hill 262.[63] Marking the occasion, former President of the United States Dwight D. Eisenhower commented that "no other battlefield presented such a horrible sight of death, hell, and total destruction."[64] The Mémorial de Coudehard–Montormel museum was constructed on the same site on the battle's 50th anniversary in 1994.[65]

In popular culture

The battle of Hill 262 is featured in the final level of the Polish campaign during the World War II video game Call of Duty 3.

Notes

- Footnotes

- ↑ Among others these included the 1st SS, 2nd SS, 9th SS, 10th SS, 12th SS, 2nd and 116th Panzer Divisions, and the 3rd Parachute, 84th, 276th, 277th, 326th, 353rd and 363rd Infantry Divisions.[4][5]

- ↑ According to McGilvray, around 500 dead and 1,000 captured.[6]

- ↑ Jarymowycz gives four battlegroups, but this figure is unsupported by other sources.[21]

- ↑ This battlegroup ended up "deep in the German rear" at Champeaux instead of Chambois as a result of a misunderstanding with its French civilian guide, who "disappeared at the first opportunity".[11][23] However, the error proved serendipitous when the 2nd Armoured Regiment discovered that Champeaux housed the headquarters of the 2nd SS Panzer Division. Along with quantities of prisoners and looted goods, the Poles seized orders detailing German defensive measures for I and II SS Panzer Corps.[23]

- ↑ Both the Poles and Americans claimed the capture of Chambois; Stacey writes "The impression one receives is that of Poles and Americans arriving in Chambois from opposite directions at about the same moment, though the Americans may have been in greater strength."[22]

- ↑ Reynolds implies that only Point 262N is referred to as Mont Ormel,[33] although other sources give this name to the entire ridge.[5][25]

- ↑ This group of captives was subsequently handed over to the Americans in Chambois.[25]

- ↑ McGilvray identifies these as the 3rd Parachute, 84th, 276th, 277th, 326th, 353rd and 363rd Infantry Divisions, and the 2nd, 116th, 1st SS, 10th SS, and 12th SS Panzer Divisions.[5]

- ↑ According to Reynolds a shallow stretch of the Dives between Magny and Moissy, approximately 5 kilometres (3.1 mi) long, was still passable. Although under indirect artillery fire the river could be waded in this area.[3]

- ↑ The times given for this are variously: after 09:00 (Reynolds (2002));[3] 11:00 (McGilvray);[45] and after 15:00 (Reynolds (2001)).[46] McGilvray also credits a 75mm or 88mm anti-tank gun, rather than a Panther tank.[45] However, the sources agree that five Shermans were destroyed from the direction of Point 239.

- Citations

- 1 2 Williams, p. 204

- ↑ Hastings (2006), p. 306

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Reynolds (2002), p. 87

- 1 2 Hastings (2006), p. 303

- 1 2 3 4 McGilvray, p. 41

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 McGilvray, p. 54

- 1 2 3 4 5 Reynolds (2001), p. 280

- ↑ Wilmot, pp. 390–392

- ↑ Hastings (2006), pp. 250–252

- ↑ Williams, p. 197

- 1 2 3 Hastings (1999), p. 356

- ↑ D'Este, p. 404

- ↑ Hastings (2006), p. 296

- ↑ Hastings (2006), p. 301

- ↑ Reid, pp. 357 and 366

- 1 2 3 4 Bercuson, p. 230

- ↑ "Archives Normandie 1939-45". archivesnormandie39-45.org. Retrieved 21 June 2010.

- ↑ Copp (2006), p. 104

- ↑ Wilmot, p. 419

- ↑ Stacey, pp. 259-260

- ↑ Jarymowycz, p. 192

- 1 2 Stacey, p. 260

- 1 2 McGilvray, p.37

- ↑ Copp (2003), p. 240

- 1 2 3 4 Copp (2003), p. 243

- 1 2 Stacey, p. 261

- 1 2 Jarymowycz, p. 195

- 1 2 3 Hastings (2006), p. 304

- ↑ Copp (2003), p. 244

- ↑ Wilmot, p. 422

- ↑ Wilmot, p.423

- 1 2 3 4 5 McGilvray, p. 46

- 1 2 3 4 Reynolds (2001), p. 273

- 1 2 3 Stacey, p. 262

- ↑ Dallas, p. 158

- ↑ Lucas & Barker, p. 143

- ↑ Lucas & Barker, p. 144

- ↑ McGilvray, pp. 46–47

- 1 2 3 4 5 McGilvray, p. 47

- 1 2 Reynolds (2001), pp. 273–274

- 1 2 3 McGilvray, p. 48

- ↑ D'Este, p. 456

- 1 2 Reynolds (2001), p. 274

- 1 2 3 McGilvray, p. 50

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 McGilvray, p. 51

- 1 2 Reynolds (2001), p. 279

- 1 2 3 4 Van Der Vat, p. 168

- 1 2 3 4 5 D'Este, p. 458

- 1 2 3 4 McGilvray, p. 53

- ↑ Lucas & Barker, p. 147

- ↑ Reynolds (2002), p. 87–88

- 1 2 "August 20th: the counter-attack of 2nd SS-PanzerKorps". memorial-montormel.org. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ↑ Stacey, p. 263

- 1 2 Jarymowycz, p. 196

- ↑ McGilvray, pp. 51–53

- ↑ Florentin (1967), pp. 300-301, quoting and translating Sévigny (1946), p.75.

- ↑ Stacey, p. 264

- ↑ Bercuson, p. 232

- 1 2 Lucas & Barker, p. 148

- 1 2 Hastings (2006), p. 313

- ↑ Copp (2003), p. 249

- ↑ Dallas, p. 160

- ↑ "Memorial Montormel - Monument". memorial-montormel.org. Retrieved 21 June 2010.

- ↑ Guttman, Jon (September 2001). "World War II: Closing the Falaise Pocket". World War II magazine. Retrieved June 18, 2008.

- ↑ "Memorial Montormel - Museum". memorial-montormel.org. Retrieved 21 June 2010.

References

- Bercuson, David (2004) [1996]. Maple Leaf Against the Axis. Red Deer Press. ISBN 0-88995-305-8.

- Copp, Terry (2006). Cinderella Army: The Canadians in Northwest Europe, 1944-1945. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-3925-1.

- Copp, Terry (2004) [2003]. Fields of Fire: The Canadians in Normandy. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-3780-1. OCLC 56329119.

- Dallas, Gregor (2005). 1945: The War That Never Ended. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-10980-6.

- D'Este, Carlo (1983). Decision in Normandy. Konecky & Konecky. ISBN 1-56852-260-6.

- Florentin, Eddy (1967) [1965]. The Battle of the Falaise Gap: An Army Dies in Normandy (First American ed.). Hawthorn Books.

- Hastings, Max (1999) [1984]. Overlord: D-Day and the Battle for Normandy. Pan Books. ISBN 0-330-39012-0.

- Hastings, Max (2006) [1984]. Overlord: D-Day and the Battle for Normandy. Vintage Books USA; Reprint edition. ISBN 0-307-27571-X.

- Jarymowycz, Roman (2001). Tank Tactics; from Normandy to Lorraine. Lynne Rienner. ISBN 1-55587-950-0.

- Keegan, John (1994) [1982]. Six Armies in Normandy. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-023542-5.

- Koskodan, Kenneth (2009). No Greater Ally: The Untold Story of Poland's Forces in World War II. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84908-479-6.

- Latawski, Paul (2004). Battle Zone Normandy: Falaise Pocket. Sutton Publishing. ISBN 0-7509-3014-4.

- Lucas, James; Barker, James (1978). The Killing Ground, The Battle of the Falaise Gap, August 1944. BT Batsford Ltd. ISBN 0-7134-0433-7.

- Maczek, Stanisław (1967). Avec Mes Blindés (in French). Paris: Press de la Cite.

- Maczek, Stanisław (2006) [1944]. "The First Polish Armoured Division in Normandy". Canadian Military History. Wilfrid Laurier University Press. 15 (2): 51–70. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- McGilvray, E. (2005). The Black Devil's March - A Doomed Odyssey: The 1st Polish Armoured Division 1939-1945. Helion & Company Ltd. ISBN 1-874622-42-6.

- Reid, Brian (2005). No Holding Back. Robin Brass Studio. ISBN 1-896941-40-0.

- Reynolds, Michael (2001) [1997]. Steel Inferno: I SS Panzer Corps in Normandy. Da Capo Press Inc. ISBN 1-885119-44-5.

- Reynolds, Michael (2002). Sons of the Reich: The History of II SS Panzer Corps in Normandy, Arnhem, the Ardennes and on the Eastern Front. Casemate Publishers and Book Distributors. ISBN 0-9711709-3-2.

- Sévigny, Pierre (1946). Face a l'Ennemi (in French). Montreal: Beauchemin.

- Stacey, Colonel Charles Perry; Bond, Major C.C.J. (1960). "Official History of the Canadian Army in the Second World War: Volume III. The Victory Campaign: The operations in North-West Europe 1944-1945" (PDF). The Queen's Printer and Controller of Stationery Ottawa. Retrieved 2008-08-20.

- Van Der Vat Da, Dan (2003). D-Day; The Greatest Invasion, A People's History. Madison Press Limited. ISBN 1-55192-586-9.

- Williams, Andrew (2004). D-Day to Berlin. Hodder. ISBN 0-340-83397-1.

Coordinates: 48°50′31″N 0°9′29″E / 48.84194°N 0.15806°E