Hill–Sachs lesion

| Hill–Sachs lesion | |

|---|---|

| |

| Anterior shoulder dislocation on X-ray with a large Hill–Sachs lesion | |

| Classification and external resources |

A Hill–Sachs lesion, or Hill–Sachs fracture, is a cortical depression in the posterolateral head of the humerus. It results from forceful impaction of the humeral head against the anteroinferior glenoid rim when the shoulder is dislocated anteriorly.

Causes

The lesion is associated with anterior or posterior shoulder dislocation.[1] When the humerus is driven from the glenohumeral cavity, its relatively soft head impacts against the anterior edge of the glenoid. The result is a divot or flattening in the posterolateral aspect of the humeral head, usually opposite the coracoid process. The mechanism which leads to shoulder dislocation is usually traumatic but can vary, especially if there is history of previous dislocations. Sports, falls, seizures, assaults, throwing, reaching, pulling on the arm, or turning over in bed can all be causes of anterior dislocation.

Clinical relevance

The incidence of Hill–Sachs lesion is not known with certainty. It has been reported to be present in 40% to 90% of patients presenting with anterior shoulder instability, that is subluxation or dislocation.[2][3] In those who have recurrent events, it may be as high as 100%.[4] Its presence is a specific sign of dislocation and can thus be used as an indicator that dislocation has occurred even if the joint has since regained its normal alignment. The average depth of Hill–Sachs lesion has been reported as 4.1 mm. Large, engaging Hill-Sachs fractures can contribute to shoulder instability and will often cause painful clicking, catching, or popping.

Diagnosis

Imaging diagnosis conventionally begins with plain film radiography. Generally, AP radiographs of the shoulder with the arm in internal rotation offer the best yield while axillary views and AP radiographs with external rotation tend to obscure the defect. However, pain and tenderness in the injured joint make appropriate positioning difficult and in a recent study of plain film x-ray for Hill–Sachs lesions, the sensitivity was only about 20%. i.e. the finding was not visible on plain film x-ray about 80% of the time.[5]

By contrast, studies have shown the value of ultrasonography in diagnosing Hill–Sachs lesions. In a population with recurrent dislocation using findings at surgery as the gold standard, a sensitivity of 96% was demonstrated.[6] In a second study of patients with continuing shoulder instability after trauma, and using double contrast CT as a gold standard, a sensitivity of over 95% was demonstrated for ultrasound.[7] It should be borne in mind that in both those studies, patients were having continuing problems after initial injury, and therefore the presence of a Hill–Sachs lesion was more likely. Nevertheless, ultrasonography, which is noninvasive and free from radiation, offers important advantages.

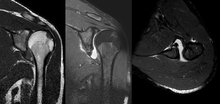

MRI has also been shown to be highly reliable for the diagnosis of Hill-Sachs (and Bankart) lesions. One study used challenging methodology. First of all, it applied to those patients with a single, or first time, dislocation. Such lesions were likely to be smaller and therefore more difficult to detect. Second, two radiologists, who were blinded to the surgical outcome, reviewed the MRI findings, while two orthopedic surgeons, who were blinded to the MRI findings, reviewed videotapes of the arthroscopic procedures. Coefficiency of agreement was then calculated for the MRI and arthroscopic findings and there was total agreement ( kappa = 1.0) for Hill-Sachs and Bankart lesions.[8]

Treatment

The decisions involved in the repair of the Hill–Sachs lesion are complex. First, it is not repaired simply because of its existence, but because of its association with continuing symptoms and instability. This may be of greatest importance in the under-25-year-old and in the athlete involved in throwing activities. The Hill-Sachs role in continuing symptoms, in turn, may be related to its size and large lesions, particularly if involving greater than 20% of the articular surface, may impinge on the glenoid fossa (engage), promoting further episodes of instability or even dislocation. Also, it is a fracture, and associated bony lesions or fractures may coexist in the glenoid, such as the so-called bony Bankart lesion. Consequently, its operative treatment may include some form of bony augmentation, such as the Latarjet or similar procedure. Finally, there is no guarantee that associated non-bony lesions, such as a Bankart lesion, SLAP tear, or biceps tendon injury, may not be present and require intervention.[9]

Eponym

The lesion is named after Harold Arthur Hill (1901–1973) and Maurice David Sachs (1909–1987), two radiologists from San Francisco, USA. In 1940, they published a report of 119 cases of shoulder dislocation and showed that the defect resulted from direct compression of the humeral head. Before their paper, although the fracture was already known to be a sign of shoulder dislocation, the precise mechanism was uncertain.[10]

See also

References

- ↑ Calandra, Joseph (December 1989). "The incidence of Hill-Sachs lesions in initial anterior shoulder disloactions". The Journal of Arthroscopic & Related Surgery. 5 (4): 254–257. PMID 2590322. doi:10.1016/0749-8063(89)90138-2. Retrieved 11 May 2014.

- ↑ Taylor DC, Arciero RA (May–Jun 1997). "Pathologic changes associated with shoulder dislocations. Arthroscopic and physical examination findings in first-time, traumatic anterior dislocations". Am J Sports Med. 25 (3): 306–11. PMID 9167808. doi:10.1177/036354659702500306.

- ↑ Calandra JJ, Baker CL, Uribe J (1989). "The incidence of Hill-Sachs lesions in initial anterior shoulder dislocations". Arthroscopy. 5 (4): 254–7. PMID 2590322. doi:10.1016/0749-8063(89)90138-2.

- ↑ Yiannakopoulos CK, Mataragas E, Antonogiannakis E (Sep 2007). "A comparison of the spectrum of intra-articular lesions in acute and chronic anterior shoulder instability". Arthroscopy. 23 (9): 985–90. PMID 17868838. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2007.05.009.

- ↑ Auffarth A, Mayer M, Kofler B, Hitzl W, Bogner R, Moroder P, Korn G, Koller H, Resch H (Nov 2013). "The interobserver reliability in diagnosing osseous lesions after first-time anterior shoulder dislocation comparing plain radiographs with computed tomography scans". J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 22 (11): 1507–13. PMID 23790679. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2013.04.020.

- ↑ Cicak N, Bilić R, Delimar D (Sep 1998). "Hill-Sachs lesion in recurrent shoulder dislocation: sonographic detection". J Ultrasound Med. 17 (9): 557–60. PMID 9733173.

- ↑ Pancione L, Gatti G, Mecozzi B (Jul 1997). "Diagnosis of Hill-Sachs lesion of the shoulder. Comparison between ultrasonography and arthro-CT". Acta Radiol. 38 (4): 523–6. PMID 9240671. doi:10.1080/02841859709174380.

- ↑ Kirkley A, Litchfield R, Thain L, Spouge A (May 2003). "Agreement between magnetic resonance imaging and arthroscopic evaluation of the shoulder joint in primary anterior dislocation of the shoulder". Clin J Sport Med. 13 (3): 148–51. PMID 12792208. doi:10.1097/00042752-200305000-00004.

- ↑ Streubel PN, Krych AJ, Simone JP, Dahm DL, Sperling JW, Steinmann SP, O'Driscoll SW, Sanchez-Sotelo J (May 2014). "Anterior glenohumeral instability: a pathology-based surgical treatment strategy". J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 22 (5): 283–94. PMID 24788444. doi:10.5435/JAAOS-22-05-283.

- ↑ Hill HA, Sachs MD (1940). "The grooved defect of the humeral head: a frequently unrecognized complication of dislocations of the shoulder joint". Radiology. 35: 690–700. doi:10.1148/35.6.690.

External links

- Hill-Sachs lesions (frontal X-ray) - szote.u-szedeg.hu.

- http://www.shoulderus.com/ultrasound-of-the-shoulder/proximal-humerus-fracture-ultrasound-hill-sachs-lesion