Heyde's syndrome

| Heyde's syndrome | |

|---|---|

| |

| A stenotic aortic valve | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | Cardiology, general surgery |

Heyde's syndrome is a syndrome of gastrointestinal bleeding from angiodysplasia in the presence of aortic stenosis.[1][2]

It is named after Edward C. Heyde, MD who first noted the association in 1958.[3] It is caused by the induction of Von Willebrand disease type IIA (vWD-2A) by a depletion of Von Willebrand factor (vWF) in blood flowing through the narrowed valvular stenosis.[4][5]

Pathophysiology

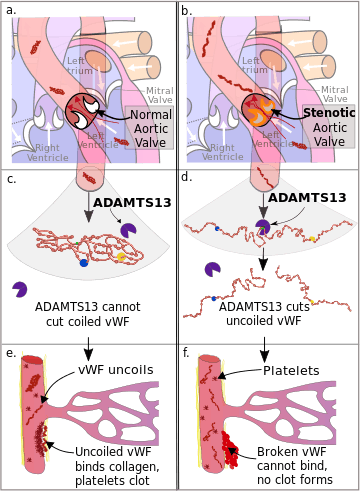

a. von Willebrand Factor (vWF) passes through a normal aortic valve and remains in its coiled form.

b. vWF passes through a stenotic aortic valve and uncoils.

c. Coiled vWF is unaffected by the catabolic enzyme ADAMTS13.

d. Uncoiled vWF is cleaved in two by ADAMTS13.

e. In damaged arterioles vWF uncoils and becomes active. It binds collagen, platelets bind to vWF, and a clot forms.

f. Inactive vWF cannot bind to the collagen, no clot forms.

Von Willebrand factor is synthesized in the walls of the blood vessels and circulates freely in the blood in a folded form. When it encounters damage to the wall of a blood vessel, particularly in situations of high velocity blood flow, it binds to the collagen beneath the damaged endothelium and uncoils into its active form. Platelets are attracted to this activated form of von Willebrand factor and they accumulate and block the damaged area, preventing bleeding (see von Willebrand factor).

In people with aortic valve stenosis, the stenotic aortic valve becomes increasingly narrowed resulting in an increase the speed of the blood through the valve in order to maintain cardiac output. This combination of a narrow opening and a higher flow rate results in an increased shear stress on the blood. This higher stress causes von Willebrand factor to unravel in the same way it would on encountering an injury site.[6][7][8] As part of the normal homeostasis of the blood, when von Willebrand factor changes conformation into its active state, it is degraded by its natural catabolic enzyme ADAMTS13, rendering it incapable of binding the collagen at an injury site.[4][6] As the quantity of von Willebrand factor in the blood decreases, the rate of bleeding dramatically increases.[9]

The unraveling of high molecular weight von Willebrand factor in conditions of high shear stress is essential in the prevention of bleeding in the vasculature of the gastrointestinal system where small arterioles are common, as platelets cannot bind to damaged blood vessel walls well in such conditions.[7] This is particularly true in the presence of intestinal angiodysplasia, where arteriovenous malformations lead to very high blood flow, and so the loss of von Willebrand factor can lead to much more extensive bleeding from these lesions.[9][10] When people with aortic stenosis also have gastrointestinal bleeding, it is invariably from angiodysplasia.[4][7]

It has been hypothesized that defects in high molecular weight von Willebrand factor could actually be the cause the arteriovenus malformations in intestinal angiodysplasia, rather than just making existing angiodysplasic lesions bleed. This hypothesis is complicated by the extremely high rates of intestinal angiodysplasia in older people (who also have the highest rate of aortic stenosis), and thus requires further research for confirmation.[4][11]

Diagnosis

Heyde's syndrome is now known to be gastrointestinal bleeding from angiodysplasic lesions due to acquired vWD-2A deficiency secondary to aortic stenosis, and the diagnosis is made by confirming the presence of those three things. Gastrointestinal bleeding may present as bloody vomit, dark, tarry stool from metabolized blood, or fresh blood in the stool. In a person presenting with these symptoms, endoscopy, gastroscopy, and/or colonoscopy should be performed to confirm the presence of angiodysplasia.[12][13] Aortic stenosis can be diagnosed by auscultation for characteristic heart sounds, particularly a crescendo-decrescendo (i.e., 'ejection') murmur, followed by echocardiography to measure aortic valve area (see diagnosis of aortic stenosis). While Heyde's syndrome may exist alone with no other symptoms of aortic stenosis,[2] the person could also present with evidence of heart failure, fainting, or chest pain. Finally, Heyde's syndrome can be confirmed using blood tests for vWD-2A, although traditional blood tests for von Willebrand factor may result in false negatives due to the subtlety of the abnormality.[13] The gold standard for diagnosis is gel electrophoresis; in people with vWD-2A, the large molecular weight von Willebrand factors will be absent from the SDS-agarose electrophoresis plate.[2]

Management

The definitive treatment for Heyde's syndrome is surgical replacement of the aortic valve.[10][14] Recently, it has been proposed that transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) can also be used for definitive management.[15] Direct surgical treatment of the bleeding (e.g. surgical resection of the bleeding portion of the bowel) is only rarely effective.[14][16]

Medical management of symptoms is possible also, although by necessity temporary, as definitive surgical management is required to bring levels of von Willebrand factor back to normal.[4] In severe bleeding, blood transfusions and IV fluid infusions can be used to maintain blood pressure. In addition, desmopressin (DDAVP) is known to be effective in people with von Willebrand's disease,[17][18] including people with valvular heart disease.[19][20] Desmopressin stimulates release of von Willebrand factor from blood vessel endothelial cells by acting on the V2 receptor, which leads to decreased breakdown of Factor VIII. Desmopressin is thus sometimes used directly to treat mild to moderate acquired von Willebrand's disease and is an effective prophylactic agent for the reduction of bleeding during heart valve replacement surgery.[19][20]

Epidemiology

The exact prevalence of the syndrome is unknown, because both aortic stenosis and angiodysplasia are common diseases in the elderly. A retrospective chart review of 3.8 million people in Northern Ireland found that the incidence of gastrointestinal bleeding in people with any diagnosis of aortic stenosis (they did not subgroup people by severity) was just 0.9%. They also found that the reverse correlation—the incidence of aortic stenosis in people with gastrointestinal bleeding—was 1.5%.[21] However, in 2003 a study of 50 people with aortic stenosis severe enough to warrant immediate valve replacement found GI bleeding in 21% of people,[10] and another study done in the USA looking at angiodysplasia rather than GI bleeding found that the prevalence of aortic stenosis was 31% compared to 14% in the control group.[4][22]

History

The American internist Edward C. Heyde originally described the syndrome in a 1958 letter to the New England Journal of Medicine, reporting on ten patients with the association.[23] Edward Heyde, MD Graduated from Johns Hopkins School of Medicine in 1938, served three years in the Army Medical Corps in WWII and joined the Vancouver Clinic, Vancouver, Washington in 1948, practicing medicine there for 31 years. He died on October 13, 2004

In the 45 years following its initial description, no plausible explanations could be found for the association between aortic valve stenosis and gastrointestinal bleeding. Indeed, the association itself was questioned by a number of researchers.[5][24] Several studies demonstrated a statistically significant association between aortic stenosis and gastrointestinal bleeding,[25][26][27] and in 1987 King et al. even noted the successful resolution of bleeding symptoms with aortic valve replacement in 93% of people, compared to just 5% in people where the bleeding was treated surgically.[16] However, the potential causal association between the two conditions remained elusive and controversial.

Several hypotheses for the association were proposed, the most prominent being the idea that there is no causal relationship between aortic stenosis and gastrointestinal bleeding, they are both just common conditions in the elderly, and they sometimes overlap. Other hypotheses included hypoxia of the colonic mucosa and bowel ischemia due to low blood flow, both of which were discounted by later research.[4][5] Another early hypothesis of note was proposed by Greenstein et al. in 1986.[27] They suggested that GI bleeding could be caused by thinning of the wall of the cecum due to abnormal pulse waves in the ileocolic artery (an artery that supplies blood to the cecum) causing dilation of that artery. Specifically, they note that the usual anacrotic and dicrotic notches were absent from the pulse waves of their people with aortic stenosis. There has been no further research investigating this hypothesis, however, as it has been eclipsed by newer research into acquired von Willebrand’s disease.

The important role of depletion of von Willebrand factor in aortic stenosis was first proposed in 1992 by Warkentin et al.[7] They noted a known association between aortic stenosis (in addition to other cardiac diseases) and acquired von Willebrand's disease type IIA,[20] which is corrected by surgical replacement of the aortic valve. They also noted that von Willebrand's disease is known to cause bleeding from angiodysplasia. Based on these facts, they hypothesized that acquired von Willebrand's disease is the true culprit behind gastrointestinal bleeding in aortic stenosis. They also proposed a possible mechanism for the acquired von Willebrand's disease, noting that von Willebrand factor is most active in 'high shear' vessels (meaning small vessels in which blood flows rapidly). They used this fact to hypothesize that this may mean that von Willebrand factor is activated in the narrowed stenotic aortic valve and thus cleared from circulation at a much higher rate than in healthy individuals.

This hypothesis received strong support in 2003 by the publication of a report by Vincentelli et al. that demonstrated a strong association between von Willebrand factor defects and the severity of aortic valve stenosis.[10] They also showed these defects resolved within hours following aortic valve replacement surgery and remained resolved in most people, although in some people the von Willebrand factor defects had returned at six months. Following this observation the shear stress dependent depletion of von Willebrand factor was confirmed, and the protease responsible, ADAMTS13, was identified.[4]

References

- ↑ Ramrakha, Punit; Hill, Jonathan (2012-02-23). Oxford Handbook of Cardiology. OUP Oxford. p. 702. ISBN 9780199643219. Retrieved 9 July 2015.

- 1 2 3 Massyn MW, Khan SA (2009). "Heyde syndrome: a common diagnosis in older patients with severe aortic stenosis". Age and Ageing. 38 (3): 267–70; discussion 251. ISSN 1468-2834. PMID 19276092. doi:10.1093/ageing/afp019.

- ↑ Heyde, Edward C. (1958). "Gastrointestinal Bleeding in Aortic Stenosis". The New England Journal of Medicine. 259 (4): 196–196. ISSN 0028-4793. doi:10.1056/NEJM195807242590416.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Loscalzo J (2012). "From clinical observation to mechanism--Heyde's syndrome". The New England Journal of Medicine. 367 (20): 1954–6. PMID 23150964. doi:10.1056/NEJMcibr1205363.

- 1 2 3 Pate GE, Chandavimol M, Naiman SC, Webb JG (2004). "Heyde's syndrome: a review". The Journal of Heart Valve Disease. 13 (5): 701–12. ISSN 0966-8519. PMID 15473466.

- 1 2 Crawley JT, de Groot R, Xiang Y, Luken BM, Lane DA (2011). "Unraveling the scissile bond: how ADAMTS13 recognizes and cleaves von Willebrand factor". Blood. 118 (12): 3212–21. ISSN 1528-0020. PMC 3179391

. PMID 21715306. doi:10.1182/blood-2011-02-306597.

. PMID 21715306. doi:10.1182/blood-2011-02-306597. - 1 2 3 4 Warkentin TE, Moore JC, Morgan DG (1992). "Aortic stenosis and bleeding gastrointestinal angiodysplasia: is acquired von Willebrand's disease the link?". The Lancet. 340 (8810): 35–7. ISSN 0140-6736. PMID 1351610. doi:10.1016/0140-6736(92)92434-H.

- ↑ Tsai HM, Sussman II, Nagel RL (1994). "Shear stress enhances the proteolysis of von Willebrand factor in normal plasma". Blood. 83 (8): 2171–9. ISSN 0006-4971. PMID 8161783.

- 1 2 Veyradier A, Balian A, Wolf M, Giraud V, Montembault S, Obert B, Dagher I, Chaput JC, Meyer D, Naveau S (2001). "Abnormal von Willebrand factor in bleeding angiodysplasias of the digestive tract". Gastroenterology. 120 (2): 346–53. ISSN 0016-5085. PMID 11159874. doi:10.1053/gast.2001.21204.

- 1 2 3 4 Vincentelli A, Susen S, Le Tourneau T, Six I, Fabre O, Juthier F, Bauters A, Decoene C, Goudemand J, Prat A, Jude B (2003). "Acquired von Willebrand syndrome in aortic stenosis". The New England Journal of Medicine. 349 (4): 343–9. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 12878741. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa022831.

- ↑ Franchini M, Mannucci PM (2013). "Von Willebrand disease-associated angiodysplasia: a few answers, still many questions". British Journal of Haematology. 161 (2): 177–82. ISSN 1365-2141. PMID 23432086. doi:10.1111/bjh.12272.

- ↑ Goldman, Lee; Schafer, Andrew I. (2015-04-21). Goldman-Cecil Medicine: Expert Consult - Online. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 1172.e3. ISBN 9780323322850.

- 1 2 Warkentin TE, Moore JC, Anand SS, Lonn EM, Morgan DG (2003). "Gastrointestinal bleeding, angiodysplasia, cardiovascular disease, and acquired von Willebrand syndrome". Transfusion Medicine Reviews. 17 (4): 272–86. ISSN 0887-7963. PMID 14571395. doi:10.1016/S0887-7963(03)00037-3.

- 1 2 Jackson CS, Gerson LB (2014). "Management of gastrointestinal angiodysplastic lesions (GIADs): a systematic review and meta-analysis". The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 109 (4): 474–83; quiz 484. ISSN 1572-0241. PMID 24642577. doi:10.1038/ajg.2014.19.

- ↑ Godino C, Lauretta L, Pavon AG, Mangieri A, Viani G, Chieffo A, Galaverna S, Latib A, Montorfano M, Cappelletti A, Maisano F, Alfieri O, Margonato A, Colombo A (2013). "Heyde's syndrome incidence and outcome in patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve implantation". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 61 (6): 687–9. ISSN 1558-3597. PMID 23391203. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2012.10.041.

- 1 2 King RM, Pluth JR, Giuliani ER (1987). "The association of unexplained gastrointestinal bleeding with calcific aortic stenosis". The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 44 (5): 514–6. ISSN 0003-4975. PMID 3499881. doi:10.1016/S0003-4975(10)62112-1.

- ↑ Siew DA, Mangel J, Laudenbach L, Schembri S, Minuk L (2014). "Desmopressin responsiveness at a capped dose of 15 μg in type 1 von Willebrand disease and mild hemophilia A". Blood Coagulation & Fibrinolysis. 25 (8): 820–3. ISSN 1473-5733. PMID 24911459. doi:10.1097/MBC.0000000000000158.

- ↑ Federici AB, Mazurier C, Berntorp E, Lee CA, Scharrer I, Goudemand J, Lethagen S, Nitu I, Ludwig G, Hilbert L, Mannucci PM (2004). "Biologic response to desmopressin in patients with severe type 1 and type 2 von Willebrand disease: results of a multicenter European study". Blood. 103 (6): 2032–8. ISSN 0006-4971. PMID 14630825. doi:10.1182/blood-2003-06-2072.

- 1 2 Jin L, Ji HW (2015). "Effect of desmopressin on platelet aggregation and blood loss in patients undergoing valvular heart surgery". Chinese Medical Journal. 128 (5): 644–7. ISSN 0366-6999. PMC 4834776

. PMID 25698197. doi:10.4103/0366-6999.151663.

. PMID 25698197. doi:10.4103/0366-6999.151663. - 1 2 3 Salzman EW, Weinstein MJ, Weintraub RM, Ware JA, Thurer RL, Robertson L, Donovan A, Gaffney T, Bertele V, Troll J (1986). "Treatment with desmopressin acetate to reduce blood loss after cardiac surgery. A double-blind randomized trial". The New England Journal of Medicine. 314 (22): 1402–6. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 3517650. doi:10.1056/NEJM198605293142202.

- ↑ Pate GE, Mulligan A (2004). "An epidemiological study of Heyde's syndrome: an association between aortic stenosis and gastrointestinal bleeding". The Journal of Heart Valve Disease. 13 (5): 713–6. ISSN 0966-8519. PMID 15473467.

- ↑ Batur P, Stewart WJ, Isaacson JH (2003). "Increased prevalence of aortic stenosis in patients with arteriovenous malformations of the gastrointestinal tract in Heyde syndrome". Archives of Internal Medicine. 163 (15): 1821–4. ISSN 0003-9926. PMID 12912718. doi:10.1001/archinte.163.15.1821.

- ↑ Heyde EC (1958). "Gastrointestinal bleeding in aortic stenosis". N. Engl. J. Med. 259 (4): 196. doi:10.1056/NEJM195807242590416.

- ↑ Gostout CJ (1995). "Angiodysplasia and aortic valve disease: let's close the book on this association". Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 42 (5): 491–3. ISSN 0016-5107. PMID 8566646. doi:10.1016/S0016-5107(95)70058-7.

- ↑ Cody MC, O'Donovan TP, Hughes RW (1974). "Idiopathic gastrointestinal bleeding and aortic stenosis". The American Journal of Digestive Diseases. 19 (5): 393–8. ISSN 0002-9211. PMID 4545225. doi:10.1007/bf01255601.

- ↑ Williams RC (1961). "Aortic stenosis and unexplained gastrointestinal bleeding". Archives of Internal Medicine. 108 (6): 859–63. ISSN 0003-9926. PMID 14040275. doi:10.1001/archinte.1961.03620120043007.

- 1 2 Greenstein RJ, McElhinney AJ, Reuben D, Greenstein AJ (1986). "Colonic vascular ectasias and aortic stenosis: coincidence or causal relationship?". American Journal of Surgery. 151 (3): 347–51. ISSN 0002-9610. PMID 3485386. doi:10.1016/0002-9610(86)90465-4.