Armenian neopaganism

.png)

Armenian Neopaganism, or Hetanism (Armenian: Հեթանոսութիւն Hetanosutiwn; a cognate word of "Heathenism"), is a Neopagan religion of reconstructionist kind, constituting an ethnic religion of the Armenians.[1] The followers of the movement call themselves Hetans (Armenian: հեթանոս Hetanos, which means "Heathen", thus "ethnic", each of them being loanwords from the Greek ἔθνος, ethnos)[2] or Arordi, meaning the Children of Ari.[3]

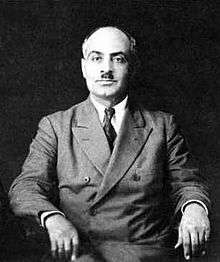

The rebirth of Armenian paganism has antecedents in the early 20th century, with the doctrine of Tseghakron (Ցեղակրօն, literally "national religion") of the nationalist politician and political theorist Garegin Nzhdeh.[4] It took an institutional form in 1991, just after the collapse of the Soviet Union in a climate of national reawakening, when armenologist Slak Kakosyan founded the "Order of the Children of Ari" (Arordineri Ukht).[5]

History

Nzhdeh and Kakosyan

The institutional form of Armenian Hetanism, the "Order of the Children of Ari" (Arordineri Ukht in Armenian speech) was established in 1991 by the armenologist Slak (formerly Edik) Kakosyan.[6] He belonged to a generation of Armenian dissidents of the 1970s, at the time of Soviet Armenia; in 1979 he was expelled for promoting nationalist ideas, and fled to the United States.[7]

Kakosyan was near to the ideas and followers of Garegin Nzhdeh, a philosopher, statesman and fedayee of the first half of the 20th century, who left a big mark in the history of Armenia, and is still one of the driving forces of Armenian nationalism.[8] Nzhdeh founded a movement named Tseghakron ("the religion of the nation"), which was among the core doctrines of the Armenian Youth Federation.[9] In Garegin Nzhdeh's poetic mythology the Armenian nation is identified as Atlas upholding the ordered world,[10] and he frequently makes reference to Hayk, the mythical patriarch of the Armenians, and to Vahagn, the solar and warrior god "fighter of the serpent", as means through which raise the Armenian spirit and awaken the nation (it was the period after the Armenian Genocide of 1915).[11]

During his exile, Slak Kakosyan made extensive use of Nzhdeh's works to codify the Ukhtagirk ("Book of Vows"), the sacred text of the Armenian Neopagan movement.[12] In the book Garegin Nzhdeh is deified as an incarnation of Vahagn, re-establisher of the true faith of the Armenian nation and its Aryan values.[13] While still in the United States, Kakosyan declared that he was initiated into the ancient Armenian hereditary priesthood mentioned by Moses of Chorene, changing his forename from Edik to Slak.[14] Seemingly he became acquainted with the Zoroastrian communities of the United States.[15]

Children of Ari in the 1990s

Returning to Armenia in 1991, Slak Kakosyan gathered a community, founded the Children of Ari, and began to hold rituals on traditional Armenian holy days. The Temple of Garni became the center of the community, a Council of Priests was set up in order to manage the organisation and rites.[16] During the 1990s the group reached mediatic visibility.[17] According to ethnologist Yulia Antonyan, assistant professor of the Department of Cultural Studies at the Yerevan State University, the emergence of Hetanism is attributable to the same causes that led to the explosion of other Neopagan, but also Krishnaite and Protestant movements in the other post-Soviet countries: it is the indigenous and ethnic answer to the social and cultural upheavals that followed the collapse of the Soviet structure and its atheist and materialistic identity.[18]

Political support and grassroots spread

The founder of the currently ruling Republican Party of Armenia, Ashot Navasardyan was a Hetan, as many other members are, and the party has provided until recent times financial support for the Children of Ari.[19] Former Prime Minister of Armenia, Andranik Margaryan was amongst the sympathisers of Armenian Neopaganism, and with his financial aid the community published the Ukhtagirk and set up a memorial stele to Slak Kakosyan on the compound of the Temple of Garni.[20] Pagan festivities find support on the municipal level.[21] However, the Children of Ari has no preferential political orientation, and the priests are forbidden from joining a political party.[22] Another political party that supports Armenian Hetanism is the Union of Armenian Aryans (and its leader Armen Avetisyan), headquartered in Abovyan, a city which is the second most important center of Neopaganism after Yerevan.[23]

Although it started among the Armenian intelligentsia as a mean to reawaken the Armenian cultural identity, in more recent times the Hetan movement has expanded its contingent gaining adherents in the province, among the rural population,[24] and the Armenian diaspora.[25] Besides the philosophical approach of the intellectuals, rural people are driven to Neopaganism by different motivations: from mysticism to sentimental devotion to the gods, as reported by Antonyan through the case of a 35 years old woman, believed to be infertile, who converted after becoming pregnant praying the fertility goddess Anahit and the love and beauty goddess Astghik.[26] The woman gave her daughter the name of Nana, another form of the Armenian fertility goddess.[27]

Theory

The Ukhtagirk, the sacred "Book of Vows", suggests a monistic theology: the beginning of the first section of the book avers that «in the beginning was the Ar, and Ara was the creator».[28] The Ar is the impersonal, without qualities, transcendent principle begetting the universe, while Ara is his personal, present form or "the Creator"[29] Subsequently the book tells the myth of how Ara generates the gods[30] and the goddess Anahit gives birth to Ari (Aryan), the form of man.[31]

Ar is the life-giving root,[32] and as a word it is the origin of other words like art ("arable", culture, art), aryyun ("blood"), arganda ("womb"), Areva (the Sun), Ara (manifested Ar), Ari (acting with Ar), Chari (opposing Ar).[33] Slak Kakosyan is not credited as the "author" of the Ukhtagirk, but the "recorder" of a perceived truth inspired into him.[34]

Deities

Armenian neopaganism is polytheistic.[35] Some of the gods of their pantheon are: Hayk, the mythical founder of the Armenian nation, Aray the god of war, Barsamin the god of sky and weather, Aralez the god of the dead, Anahit the goddess of fertility and war, Mihr the solar god, Astghik the goddess of love and beauty, Nuneh the goddess of wisdom, Tir the god of art and inspiration, Tsovinar the goddess of waters, Amanor the god of hospitality, Spandaramet the goddess of death, and Gissaneh the mother goddess of nature.

Practices

.png)

Armenian Neopagan practices, rituals and representations mostly rely on the instructions given by the Ukhtagirk.[36] For example, it is common for the priests to make pilgrimage to Mount Khustup, where, according to the book, Garegin Nzhdeh experienced the presence of god Vahagn.[37] The priests hope to find the same experience.[38] The veneration of Nzhdeh and the pilgrimage to his burial, which is on the slopes of the Khustup, is also slowly developing amongst the greater Neopagan community.[39]

Also Slak Kakosyan is venerated: celebrations in honour of god Vahagn at the Temple of Garni usually start at the memorial monument to Kakosyan that the Hetans have set up where after his death his ashes were scattered to the winds.[40] A mythologisation of his personality has begun, with a collection of poems by poet Arena Aykyan, published in 2007, in which he is characterised as a divine man.[41]

Rituals

The ritual system of Armenian Hetanism includes the yearly holiday rituals as well as three rites of passage: the knunk, a complex saining ritual; the psak that is wedding, and death rituals.[42] Death rituals require the cremation of the body.[43]

The Armenian term knunk can be translated as "conversion" or "reversion" (to the native way).[44] Yulia Antonyan has observed that about 10 to 20 people take the knunk at every public ceremony at the Temple of Garni, but there are many active Neopagans who believe that in order to worship the gods of Armenia is not necessary to go through an official conversion.[45]

Temples and idols

Rituals and public ceremonies are held at ancient sacred places, often in ruins.[46] The re-appropriation of churches that were built on native sacred sites is also frequent.[47] The most important of these sites is the Temple of Garni, a Hellenistic-style temple rebuilt in 1975, which has become the main ceremonial center of the Neopagan community.[48]

The temple has been reconsecrated to Vahagn by the Hetans, despite the fact that historically it was a temple of Mihr. They have also rearranged the compound in order that it now matches spacially and hierarchically the structure of an ancient Armenian sanctuary;[49] with the addition of a sacred spring dedicated to Slak Kakosyan and an apricot tree (the sacred tree of Armenian Hetanism) it is now organised on three sacred spaces: the first level is the sacred spring, the second one is the very temple, and the third one is the sacred tree on a hill or hillrock.[50]

The Hetan temple rituals take place through a route from the spring, through the temple, to the tree.[51] Sculptures representing the gods are inspired both by historical specimens and the creativity of modern artists.[52]

Holidays

The Armenian Hetans celebrate a number of holidays:[53] Terndez, Zatik, Hambardzum, Vardavar and Khaghoghorhnek. To these holy days they add a holy day for the remembrance of ancestors (20 September), the New Year or Birthday of Vahagn (21 March) and the Navasard.

See also

References

- ↑ Antonyan 2010, pp. 104-105

- ↑ Antonyan 2010, p. 105, note 4

- ↑ Antonyan 2010, p. 105, note 4

- ↑ Antonyan 2010, p. 105

- ↑ Antonyan 2010, p. 105

- ↑ Antonyan 2010, p. 105

- ↑ Antonyan 2010, p. 105

- ↑ Antonyan 2010, p. 105

- ↑ Antonyan 2010, p. 105

- ↑ Antonyan 2010, p. 105

- ↑ Antonyan 2010, p. 105

- ↑ Antonyan 2010, p. 106

- ↑ Antonyan 2010, p. 106

- ↑ Antonyan 2010, p. 106

- ↑ Antonyan 2010, p. 106

- ↑ Antonyan 2010, p. 106, note 7

- ↑ Antonyan 2010, p. 107

- ↑ Antonyan 2010, p. 104

- ↑ Antonyan 2010, p. 107

- ↑ Antonyan 2010, p. 107, note 8

- ↑ Antonyan 2010, p. 107, note 8

- ↑ Antonyan 2010, p. 107

- ↑ Antonyan 2010, p. 107, note 12

- ↑ Antonyan 2010, p. 107

- ↑ Antonyan 2010, p. 108

- ↑ Antonyan 2010, p. 108

- ↑ Antonyan 2010, p. 109

- ↑ Antonyan 2010, p. 110

- ↑ Antonyan 2010, p. 110

- ↑ Antonyan 2010, p. 116

- ↑ Antonyan 2010, p. 110

- ↑ Antonyan 2010, p. 115

- ↑ Antonyan 2010, p. 115

- ↑ Antonyan 2010, p. 115

- ↑ Antonyan 2010, p. 116

- ↑ Antonyan 2010, p. 110

- ↑ Antonyan 2010, p. 109

- ↑ Antonyan 2010, p. 109

- ↑ Antonyan 2010, p. 110, note 14

- ↑ Antonyan 2010, p. 110

- ↑ Antonyan 2010, p. 110

- ↑ Antonyan 2010, p. 121

- ↑ Antonyan 2010, p. 121

- ↑ Antonyan 2010, p. 108, note 11

- ↑ Antonyan 2010, p. 108, note 11

- ↑ Antonyan 2010, p. 119

- ↑ Antonyan 2010, p. 119

- ↑ Antonyan 2010, p. 119

- ↑ Antonyan 2010, p. 119

- ↑ Antonyan 2010, p. 119

- ↑ Antonyan 2010, p. 119

- ↑ Antonyan 2010, p. 119

- ↑ Antonyan 2010, p. 116

Bibliography

- Konrad Siekierski, Yulia Antonyan. A Neopagan Movement in Armenia: the Children of Ara. In Native Faith and Neo-Pagan Movements in Central and Eastern Europe. Kaarina Aitamurto, Scott Simpson. Acumen Publishing, 2013. ISBN 1844656624

- Yulia Antonyan. Nzhdeh: Hero and God. Yerevan State University.

- Yulia Antonyan. "Re-creation" of a Religion: Neo-paganism in Armenia. Yerevan State University. Published on Laboratorium, n. 1, Saint-Petersburg, 2010

- Yulia Antonyan. The Aryan Myth and the New Armenian Paganism. Yerevan State University. Published in Identities and Changing World, Proceedings of the International Conference, Yerevan, 2008

- Armenian neoshamanism

- Yulia Antonyan. Magical and Healing Practices in Contemporary Urban Environment (in Armenian Cities of Yerevan, Gyumri, and Vanadzor). Published in Figuring the South Caucasus: Societies and Environment, Heinrich Böll Foundation, Tbilisi, 2008

- Yulia Antonyan. On the Name and Origins of "Chopchi" Healing Practices. Published in Bulletin of Armenian Studies, n. 1, 2006, pp. 61–66

- Yulia Antonyan. Pre-Christian Healers in a Christian Society. Published in Cultural Survival Quarterly, vol. 27.2, 2003

External links

- Order of the Children of Ari — official website