Dutch East India Company

| |

Native name | Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (VOC) |

|---|---|

| Publicly traded company | |

| Industry | Trade, manufacturing |

| Fate | Dissolved |

| Predecessor | Voorcompagnie (Compagnie van Verre, Brabantsche Compagnie, Magelhaensche Compagnie) |

| Founded | 20 March 1602[1] |

| Founder | Johan van Oldenbarnevelt |

| Defunct | 31 December 1799 |

| Headquarters |

Amsterdam, Dutch Republic (main headquarters) Batavia, Dutch East Indies (overseas administrative center) |

Area served |

Europe-Asia (Eurasia) Intra-Asia |

Key people |

Heeren XVII/Gentlemen Seventeen (Dutch Republic, 1602–1799) Governors-General of the Dutch East Indies (Batavia, 1610–1800) |

| Products | Spice, silk, porcelain, metals, livestock, tea, grains (rice, soybeans), sugarcane industry, shipbuilding industry |

|

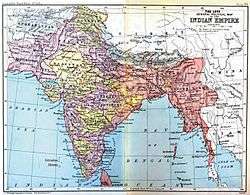

Imperial entities of India | |

| Dutch India | 1605–1825 |

|---|---|

| Danish India | 1620–1869 |

| French India | 1668–1954 |

| Casa da Índia | 1434–1833 |

| Portuguese East India Company | 1628–1633 |

| East India Company | 1612–1757 |

| Company rule in India | 1757–1858 |

| British Raj | 1858–1947 |

| British rule in Burma | 1824–1948 |

| Princely states | 1721–1949 |

| Partition of India |

1947 |

|

| |

The United East India Company or the United East Indian Company, also known as the United East Indies Company (Dutch: Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie; or Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie in modern spelling; VOC), referred to by the British as the Dutch East India Company,[2] or sometimes known as the Dutch East Indies Company, was originally established as a chartered company in 1602, when the Dutch government granted it a 21-year monopoly on the Dutch spice trade. A multinational company, it is also often considered to be the world's first truly transnational corporation.[note 1][3] In the early 1600s, the VOC became the first company in history to issue bonds and shares of stock to the general public.[note 2] In other words, the VOC was the world's first formally listed public company,[note 3] because it was the first corporation to be ever actually listed on an official (formal) stock exchange.[note 4][6] As the first historical model of the quasi-fictional concept of the megacorporation, the VOC possessed quasi-governmental powers, including the ability to wage war, imprison and execute convicts,[7] negotiate treaties, strike its own coins, and establish colonies.[8]

The VOC played a crucial role in business, financial, socio-politico-economic, military-political, diplomatic, and maritime history of the world. In the early modern period, the VOC was also the driving force behind the rise of corporate-led globalization, corporate identity, corporate social responsibility, corporate governance, corporate finance, and financial capitalism. As a transcontinental employer, the company was an early pioneer of outward foreign direct investment at the dawn of modern capitalism. With its pioneering institutional innovations and powerful roles in world history, the company was considered by many to be the first major and the most influential corporation ever.[note 5][9][10][11][12] In terms of military-political history, the VOC, along with the Dutch West India Company (WIC/GWIC), was seen as the international arm of the Dutch Republic and the symbolic power of the Dutch Empire. The VOC was historically a military-political-economic complex rather than a pure trading company (or shipping company). In terms of maritime exploration history of the world, as a major force behind the Golden Age of Dutch exploration and discovery (ca. 1590s–1720s), the VOC-funded exploratory voyages such as those led by Willem Janszoon (Duyfken), Henry Hudson (Halve Maen) and Abel Tasman revealed largely unknown landmasses to the civilized world. In the Golden Age of Netherlandish cartography, the VOC navigators and cartographers helped shape geographical knowledge of the modern world as we know them today. The commercial networks of Dutch transnational companies, like the VOC and GWIC, provided an infrastructure which was accessible to people with a scholarly interest in the exotic world.

The company was formed to profit from the Malukan spice trade, and in 1619 it established a capital in the port city of Jayakarta, changing the name to Batavia (modern-day Jakarta). Over the next two centuries the Company acquired additional ports as trading bases and safeguarded their interests by taking over surrounding territory.[13] It remained an important trading concern and paid an 18% annual dividend for almost 200 years.[14] Statistically, the VOC eclipsed all of its rivals in international trade for almost 200 years of existence.[15][16] Between 1602 and 1796 the VOC sent almost a million Europeans to work in the Asia trade on 4,785 ships, and netted for their efforts more than 2.5 million tons of Asian trade goods. By contrast, the rest of Europe combined sent only 882,412 people from 1500 to 1795, and the fleet of the British East India Company (EIC), the VOC's nearest competitor, was a distant second to its total traffic with 2,690 ships and a mere one-fifth the tonnage of goods carried by the VOC. The VOC enjoyed huge profits from its spice monopoly through most of the 17th century.[17]

Due to structural changes, the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War, and French invasion of the Netherlands, the company was nationalised in 1800,[18] and its possessions and debt were taken over by the government of the Batavian Republic (1795–1806). The VOC's territories became the Dutch East Indies and were expanded over the course of the 19th century to include the whole of the Indonesian archipelago, which would later become the modern Republic of Indonesia.

Company name, logo and flag

Around the world and especially in English-speaking countries, the VOC is widely known as the "Dutch East India Company". The name ‘Dutch East India Company’ is used to make a distinction with the [British] East India Company (EIC) and other East Indian companies (such as the Danish East India Company, French East India Company, Portuguese East India Company, and the Swedish East India Company). The abbreviation "VOC" stands for "Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie" or "Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie" in Dutch, literally meaning "United East-Indian Company", "United East-India Company", or "United East-Indies Company".

The VOC monogram was possibly the first globally-recognized corporate logo.[9] The logo of the VOC consisted of a large capital 'V' with an O on the left and a C on the right leg. It appeared on various corporate items, such as cannon and coins. The first letter of the hometown of the chamber conducting the operation was placed on top (see figure for example of the Amsterdam chamber logo). The adaptability, elegance, flexibility, simplicity, symbolism, and symmetry were considered notable characteristics of the VOC's well-designed monogram-logo, those ensured its success at a time when the concept of the corporate identity was virtually unknown.[19] An Australian vintner has used the VOC logo since the late 20th century, having re-registered the company's name for the purpose.[20]

The flag of the company was orange, white, and blue (see Dutch flag), with the company logo embroidered on it.

History

Origins

Before the Dutch Revolt, Antwerp had played an important role as a distribution centre in northern Europe. After 1591, however, the Portuguese used an international syndicate of the German Fuggers and Welsers, and Spanish and Italian firms, that used Hamburg as the northern staple port to distribute their goods, thereby cutting Dutch merchants out of the trade. At the same time, the Portuguese trade system was unable to increase supply to satisfy growing demand, in particular the demand for pepper. Demand for spices was relatively inelastic, and therefore each lag in the supply of pepper caused a sharp rise in pepper prices.

In 1580 the Portuguese crown was united in a personal union with the Spanish crown, with which the Dutch Republic was at war. The Portuguese Empire therefore became an appropriate target for Dutch military incursions. These factors motivated Dutch merchants to enter the intercontinental spice trade themselves. Further, a number of Dutchmen like Jan Huyghen van Linschoten and Cornelis de Houtman obtained first hand knowledge of the "secret" Portuguese trade routes and practices, thereby providing opportunity.[21]

The stage was thus set for the four-ship exploratory expedition by Frederick de Houtman in 1595 to Banten, the main pepper port of West Java, where they clashed with both the Portuguese and indigenous Indonesians. Houtman's expedition then sailed east along the north coast of Java, losing twelve crew to a Javanese attack at Sidayu and killing a local ruler in Madura. Half the crew were lost before the expedition made it back to the Netherlands the following year, but with enough spices to make a considerable profit.[22]

In 1598, an increasing number of fleets were sent out by competing merchant groups from around the Netherlands. Some fleets were lost, but most were successful, with some voyages producing high profits. In March 1599, a fleet of eight ships under Jacob van Neck was the first Dutch fleet to reach the 'Spice Islands' of Maluku, the source of pepper, cutting out the Javanese middlemen. The ships returned to Europe in 1599 and 1600 and the expedition made a 400 percent profit.[22]

In 1600, the Dutch joined forces with the Muslim Hituese on Ambon Island in an anti-Portuguese alliance, in return for which the Dutch were given the sole right to purchase spices from Hitu.[23] Dutch control of Ambon was achieved when the Portuguese surrendered their fort in Ambon to the Dutch-Hituese alliance. In 1613, the Dutch expelled the Portuguese from their Solor fort, but a subsequent Portuguese attack led to a second change of hands; following this second reoccupation, the Dutch once again captured Solor, in 1636.[23]

East of Solor, on the island of Timor, Dutch advances were halted by an autonomous and powerful group of Portuguese Eurasians called the Topasses. They remained in control of the Sandalwood trade and their resistance lasted throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, causing Portuguese Timor to remain under the Portuguese sphere of control.[24][25]

Formation, rise and fall

Formative years

At the time, it was customary for a company to be set up only for the duration of a single voyage and to be liquidated upon the return of the fleet. Investment in these expeditions was a very high-risk venture, not only because of the usual dangers of piracy, disease and shipwreck, but also because the interplay of inelastic demand and relatively elastic supply[26] of spices could make prices tumble at just the wrong moment, thereby ruining prospects of profitability. To manage such risk the forming of a cartel to control supply would seem logical. The English had been the first to adopt this approach, by bundling their resources into a monopoly enterprise, the English East India Company in 1600, thereby threatening their Dutch competitors with ruin.[27]

In 1602, the Dutch government followed suit, sponsoring the creation of a single "United East Indies Company" that was also granted monopoly over the Asian trade. With a capital of 6,440,200 guilders,[28] the charter of the new company empowered it to build forts, maintain armies, and conclude treaties with Asian rulers. It provided for a venture that would continue for 21 years, with a financial accounting only at the end of each decade.[27]

In February 1603, the Company seized the Santa Catarina, a 1500-ton Portuguese merchant carrack, off the coast of Singapore.[29] She was such a rich prize that her sale proceeds increased the capital of the VOC by more than 50%.[30]

Also in 1603 the first permanent Dutch trading post in Indonesia was established in Banten, West Java, and in 1611 another was established at Jayakarta (later "Batavia" and then "Jakarta").[31] In 1610, the VOC established the post of Governor General to more firmly control their affairs in Asia. To advise and control the risk of despotic Governors General, a Council of the Indies (Raad van Indië) was created. The Governor General effectively became the main administrator of the VOC's activities in Asia, although the Heeren XVII, a body of 17 shareholders representing different chambers, continued to officially have overall control.[23]

VOC headquarters were located in Ambon during the tenures of the first three Governors General (1610–1619), but it was not a satisfactory location. Although it was at the centre of the spice production areas, it was far from the Asian trade routes and other VOC areas of activity ranging from Africa to India to Japan.[32][33] A location in the west of the archipelago was thus sought. The Straits of Malacca were strategic but had become dangerous following the Portuguese conquest, and the first permanent VOC settlement in Banten was controlled by a powerful local ruler and subject to stiff competition from Chinese and English traders.[23]

In 1604, a second English East India Company voyage commanded by Sir Henry Middleton reached the islands of Ternate, Tidore, Ambon and Banda. In Banda, they encountered severe VOC hostility, sparking Anglo-Dutch competition for access to spices.[31] From 1611 to 1617, the English established trading posts at Sukadana (southwest Kalimantan), Makassar, Jayakarta and Jepara in Java, and Aceh, Pariaman and Jambi in Sumatra, which threatened Dutch ambitions for a monopoly on East Indies trade.[31]

Diplomatic agreements in Europe in 1620 ushered in a period of co-operation between the Dutch and the English over the spice trade.[31] This ended with a notorious but disputed incident known as the 'Amboyna massacre', where ten Englishmen were arrested, tried and beheaded for conspiracy against the Dutch government.[34] Although this caused outrage in Europe and a diplomatic crisis, the English quietly withdrew from most of their Indonesian activities (except trading in Banten) and focused on other Asian interests.

Growth

In 1619, Jan Pieterszoon Coen was appointed Governor-General of the VOC. He saw the possibility of the VOC becoming an Asian power, both political and economic. On 30 May 1619, Coen, backed by a force of nineteen ships, stormed Jayakarta, driving out the Banten forces; and from the ashes established Batavia as the VOC headquarters. In the 1620s almost the entire native population of the Banda Islands was driven away, starved to death, or killed in an attempt to replace them with Dutch plantations.[35] These plantations were used to grow cloves and nutmeg for export. Coen hoped to settle large numbers of Dutch colonists in the East Indies, but implementation of this policy never materialised, mainly because very few Dutch were willing to emigrate to Asia.[36]

Another of Coen's ventures was more successful. A major problem in the European trade with Asia at the time was that the Europeans could offer few goods that Asian consumers wanted, except silver and gold. European traders therefore had to pay for spices with the precious metals, which were in short supply in Europe, except for Spain and Portugal. The Dutch and English had to obtain it by creating a trade surplus with other European countries. Coen discovered the obvious solution for the problem: to start an intra-Asiatic trade system, whose profits could be used to finance the spice trade with Europe. In the long run this obviated the need for exports of precious metals from Europe, though at first it required the formation of a large trading-capital fund in the Indies. The VOC reinvested a large share of its profits to this end in the period up to 1630.[37]

The VOC traded throughout Asia. Ships coming into Batavia from the Netherlands carried supplies for VOC settlements in Asia. Silver and copper from Japan were used to trade with India and China for silk, cotton, porcelain, and textiles. These products were either traded within Asia for the coveted spices or brought back to Europe. The VOC was also instrumental in introducing European ideas and technology to Asia. The Company supported Christian missionaries and traded modern technology with China and Japan. A more peaceful VOC trade post on Dejima, an artificial island off the coast of Nagasaki, was for more than two hundred years the only place where Europeans were permitted to trade with Japan.[38] When the VOC tried to use military force to make Ming dynasty China open up to Dutch trade, the Chinese defeated the Dutch in a war over the Penghu islands from 1623–24, forcing the VOC to abandon Penghu for Taiwan. The Chinese defeated the VOC again at the Battle of Liaoluo Bay in 1633.

The Vietnamese Nguyen Lords defeated the VOC in a 1643 battle during the Trịnh–Nguyễn War, blowing up a Dutch ship. The Cambodians defeated the VOC in the Cambodian–Dutch War from 1643–44 on the Mekong River.

In 1640, the VOC obtained the port of Galle, Ceylon, from the Portuguese and broke the latter's monopoly of the cinnamon trade. In 1658, Gerard Pietersz. Hulft laid siege to Colombo, which was captured with the help of King Rajasinghe II of Kandy. By 1659, the Portuguese had been expelled from the coastal regions, which were then occupied by the VOC, securing for it the monopoly over cinnamon. To prevent the Portuguese or the English from ever recapturing Sri Lanka, the VOC went on to conquer the entire Malabar Coast from the Portuguese, almost entirely driving them from the west coast of India. When news of a peace agreement between Portugal and the Netherlands reached Asia in 1663, Goa was the only remaining Portuguese city on the west coast.[39]

In 1652, Jan van Riebeeck established an outpost at the Cape of Good Hope (the southwestern tip of Africa, now Cape Town, South Africa) to re-supply VOC ships on their journey to East Asia. This post later became a full-fledged colony, the Cape Colony, when more Dutch and other Europeans started to settle there.

VOC trading posts were also established in Persia, Bengal, Malacca, Siam, Canton, Formosa (now Taiwan), as well as the Malabar and Coromandel coasts in India. In 1662, however, Koxinga expelled the Dutch from Taiwan[40] (see History of Taiwan).

In 1663, the VOC signed the "Painan Treaty" with several local lords in the Painan area that were revolting against the Aceh Sultanate. The treaty allowed the VOC to build a trading post in the area and eventually to monopolise the trade there, especially the gold trade.[41]

By 1669, the VOC was the richest private company the world had ever seen, with over 150 merchant ships, 40 warships, 50,000 employees, a private army of 10,000 soldiers, and a dividend payment of 40% on the original investment.[42]

Many of the VOC employees inter-mixed with the indigenous peoples and expanded the population of Indos in pre-colonial history [43][44]

Reorientation

Around 1670, two events caused the growth of VOC trade to stall. In the first place, the highly profitable trade with Japan started to decline. The loss of the outpost on Formosa to Koxinga in the 1662 Siege of Fort Zeelandia and related internal turmoil in China (where the Ming dynasty was being replaced with the Qing dynasty) brought an end to the silk trade after 1666. Though the VOC substituted Bengali for Chinese silk other forces affected the supply of Japanese silver and gold. The shogunate enacted a number of measures to limit the export of these precious metals, in the process limiting VOC opportunities for trade, and severely worsening the terms of trade. Therefore, Japan ceased to function as the lynchpin of the intra-Asiatic trade of the VOC by 1685.[46]

Even more importantly, the Third Anglo-Dutch War temporarily interrupted VOC trade with Europe. This caused a spike in the price of pepper, which enticed the English East India Company (EIC) to enter this market aggressively in the years after 1672. Previously, one of the tenets of the VOC pricing policy was to slightly over-supply the pepper market, so as to depress prices below the level where interlopers were encouraged to enter the market (instead of striving for short-term profit maximisation). The wisdom of such a policy was illustrated when a fierce price war with the EIC ensued, as that company flooded the market with new supplies from India. In this struggle for market share, the VOC (which had much larger financial resources) could wait out the EIC. Indeed, by 1683, the latter came close to bankruptcy; its share price plummeted from 600 to 250; and its president Josiah Child was temporarily forced from office.[47]

However, the writing was on the wall. Other companies, like the French East India Company and the Danish East India Company also started to make inroads on the Dutch system. The VOC therefore closed the heretofore flourishing open pepper emporium of Bantam by a treaty of 1684 with the Sultan. Also, on the Coromandel Coast, it moved its chief stronghold from Pulicat to Negapatnam, so as to secure a monopoly on the pepper trade at the detriment of the French and the Danes.[48] However, the importance of these traditional commodities in the Asian-European trade was diminishing rapidly at the time. The military outlays that the VOC needed to make to enhance its monopoly were not justified by the increased profits of this declining trade.[49]

Nevertheless, this lesson was slow to sink in and at first the VOC made the strategic decision to improve its military position on the Malabar Coast (hoping thereby to curtail English influence in the area, and end the drain on its resources from the cost of the Malabar garrisons) by using force to compel the Zamorin of Calicut to submit to Dutch domination. In 1710, the Zamorin was made to sign a treaty with the VOC undertaking to trade exclusively with the VOC and expel other European traders. For a brief time, this appeared to improve the Company's prospects. However, in 1715, with EIC encouragement, the Zamorin renounced the treaty. Though a Dutch army managed to suppress this insurrection temporarily, the Zamorin continued to trade with the English and the French, which led to an appreciable upsurge in English and French traffic. The VOC decided in 1721 that it was no longer worth the trouble to try to dominate the Malabar pepper and spice trade. A strategic decision was taken to scale down the Dutch military presence and in effect yield the area to EIC influence.[50]

The 1741 Battle of Colachel by Nair warriors of Travancore under Raja Marthanda Varma defeated the Dutch. The Dutch commander Captain Eustachius De Lannoy was captured. Marthanda Varma agreed to spare the Dutch captain's life on condition that he joined his army and trained his soldiers on modern lines. This defeat in the Travancore-Dutch War is considered the earliest example of an organised Asian power overcoming European military technology and tactics; and it signalled the decline of Dutch power in India.[51]

The attempt to continue as before as a low volume-high profit business enterprise with its core business in the spice trade had therefore failed. The Company had however already (reluctantly) followed the example of its European competitors in diversifying into other Asian commodities, like tea, coffee, cotton, textiles, and sugar. These commodities provided a lower profit margin and therefore required a larger sales volume to generate the same amount of revenue. This structural change in the commodity composition of the VOC's trade started in the early 1680s, after the temporary collapse of the EIC around 1683 offered an excellent opportunity to enter these markets. The actual cause for the change lies, however, in two structural features of this new era.

In the first place, there was a revolutionary change in the tastes affecting European demand for Asian textiles, coffee and tea, around the turn of the 18th century. Secondly, a new era of an abundant supply of capital at low interest rates suddenly opened around this time. The second factor enabled the Company easily to finance its expansion in the new areas of commerce.[52] Between the 1680s and 1720s, the VOC was therefore able to equip and man an appreciable expansion of its fleet, and acquire a large amount of precious metals to finance the purchase of large amounts of Asian commodities, for shipment to Europe. The overall effect was approximately to double the size of the company.[53]

The tonnage of the returning ships rose by 125 percent in this period. However, the Company's revenues from the sale of goods landed in Europe rose by only 78 percent. This reflects the basic change in the VOC's circumstances that had occurred: it now operated in new markets for goods with an elastic demand, in which it had to compete on an equal footing with other suppliers. This made for low profit margins.[54] Unfortunately, the business information systems of the time made this difficult to discern for the managers of the company, which may partly explain the mistakes they made from hindsight. This lack of information might have been counteracted (as in earlier times in the VOC's history) by the business acumen of the directors. Unfortunately by this time these were almost exclusively recruited from the political regent class, which had long since lost its close relationship with merchant circles.[55]

Low profit margins in themselves do not explain the deterioration of revenues. To a large extent the costs of the operation of the VOC had a "fixed" character (military establishments; maintenance of the fleet and such). Profit levels might therefore have been maintained if the increase in the scale of trading operations that in fact took place had resulted in economies of scale. However, though larger ships transported the growing volume of goods, labour productivity did not go up sufficiently to realise these. In general the Company's overhead rose in step with the growth in trade volume; declining gross margins translated directly into a decline in profitability of the invested capital. The era of expansion was one of "profitless growth".[56]

Specifically: "[t]he long-term average annual profit in the VOC's 1630–70 'Golden Age' was 2.1 million guilders, of which just under half was distributed as dividends and the remainder reinvested. The long-term average annual profit in the 'Expansion Age' (1680–1730) was 2.0 million guilders, of which three-quarters was distributed as dividend and one-quarter reinvested. In the earlier period, profits averaged 18 percent of total revenues; in the latter period, 10 percent. The annual return of invested capital in the earlier period stood at approximately 6 percent; in the latter period, 3.4 percent."[56]

Nevertheless, in the eyes of investors the VOC did not do too badly. The share price hovered consistently around the 400 mark from the mid-1680s (excepting a hiccup around the Glorious Revolution in 1688), and they reached an all-time high of around 642 in the 1720s. VOC shares then yielded a return of 3.5 percent, only slightly less than the yield on Dutch government bonds.[57]

Decline and fall

However, from there on the fortunes of the VOC started to decline. Five major problems, not all of equal weight, can be used to explain its decline in the next fifty years to 1780.[58]

- There was a steady erosion of intra-Asiatic trade because of changes in the Asiatic political and economic environment that the VOC could do little about. These factors gradually squeezed the company out of Persia, Suratte, the Malabar Coast, and Bengal. The company had to confine its operations to the belt it physically controlled, from Ceylon through the Indonesian archipelago. The volume of this intra-Asiatic trade, and its profitability, therefore had to shrink.

- The way the company was organised in Asia (centralised on its hub in Batavia), that initially had offered advantages in gathering market information, began to cause disadvantages in the 18th century because of the inefficiency of first shipping everything to this central point. This disadvantage was most keenly felt in the tea trade, where competitors like the EIC and the Ostend Company shipped directly from China to Europe.

- The "venality" of the VOC's personnel (in the sense of corruption and non-performance of duties), though a problem for all East-India Companies at the time, seems to have plagued the VOC on a larger scale than its competitors. To be sure, the company was not a "good employer". Salaries were low, and "private-account trading" was officially not allowed. Not surprisingly, it proliferated in the 18th century to the detriment of the company's performance.[59] From about the 1790s onward, the phrase perished under corruption (vergaan onder corruptie, also abbreviated VOC in Dutch) came to summarise the company's future.

- A problem that the VOC shared with other companies was the high mortality and morbidity rates among its employees. This decimated the company's ranks and enervated many of the survivors.

- A self-inflicted wound was the VOC's dividend policy. The dividends distributed by the company had exceeded the surplus it garnered in Europe in every decade but one (1710–1720) from 1690 to 1760. However, in the period up to 1730 the directors shipped resources to Asia to build up the trading capital there. Consolidated bookkeeping therefore probably would have shown that total profits exceeded dividends. In addition, between 1700 and 1740 the company retired 5.4 million guilders of long-term debt. The company therefore was still on a secure financial footing in these years. This changed after 1730. While profits plummeted the bewindhebbers only slightly decreased dividends from the earlier level. Distributed dividends were therefore in excess of earnings in every decade but one (1760–1770). To accomplish this, the Asian capital stock had to be drawn down by 4 million guilders between 1730 and 1780, and the liquid capital available in Europe was reduced by 20 million guilders in the same period. The directors were therefore constrained to replenish the company's liquidity by resorting to short-term financing from anticipatory loans, backed by expected revenues from home-bound fleets.

Despite of all this, the VOC in 1780 remained an enormous operation. Its capital in the Republic, consisting of ships and goods in inventory, totalled 28 million guilders; its capital in Asia, consisting of the liquid trading fund and goods en route to Europe, totalled 46 million guilders. Total capital, net of outstanding debt, stood at 62 million guilders. The prospects of the company at this time therefore need not have been hopeless, had one of the many plans to reform it been taken successfully in hand. However, then the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War intervened. British attacks in Europe and Asia reduced the VOC fleet by half; removed valuable cargo from its control; and devastated its remaining power in Asia. The direct losses of the VOC can be calculated at 43 million guilders. Loans to keep the company operating reduced its net assets to zero.[60]

From 1720 on, the market for sugar from Indonesia declined as the competition from cheap sugar from Brazil increased. European markets became saturated. Dozens of Chinese sugar traders went bankrupt which led to massive unemployment, which in turn led to gangs of unemployed coolies. The Dutch government in Batavia did not adequately respond to these problems. In 1740, rumours of deportation of the gangs from the Batavia area led to widespread rioting. The Dutch military searched houses of Chinese in Batavia for weapons. When a house accidentally burnt down, military and impoverished citizens started slaughtering and pillaging the Chinese community.[61] This massacre of the Chinese was deemed sufficiently serious for the board of the VOC to start an official investigation into the Government of the Dutch East Indies for the first time in its history.

After the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War, the VOC was a financial wreck, and after vain attempts by the provincial States of Holland and Zeeland to reorganise it, was nationalised on 1 March 1796[62] by the new Batavian Republic. Its charter was renewed several times, but allowed to expire on 31 December 1799.[62] Most of the possessions of the former VOC were subsequently occupied by Great Britain during the Napoleonic wars, but after the new United Kingdom of the Netherlands was created by the Congress of Vienna, some of these were restored to this successor state of the old Dutch Republic by the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1814.

Organizational structure

.jpg)

The VOC is generally considered to be the world's first truly transnational corporation and it was also the first multinational enterprise to issue shares of stock to the public. Some historians such as Timothy Brook and Russell Shorto consider the VOC as the pioneering corporation in the first wave of the corporate globalization era.[9][10] The VOC was the first multinational corporation to operate officially in different continents such as Europe, Asia and Africa. While the VOC mainly operated in what later became the Dutch East Indies (modern Indonesia), the company also had important operations elsewhere. It employed people from different continents and origins in the same functions and working environments. Although it was a Dutch company its employees included not only people from the Netherlands, but also many from Germany and from other countries as well. Besides the diverse north-west European workforce recruited by the VOC in the Dutch Republic, the VOC made extensive use of local Asian labour markets. As a result, the personnel of the various VOC offices in Asia consisted of European and Asian employees. Asian or Eurasian workers might be employed as sailors, soldiers, writers, carpenters, smiths, or as simple unskilled workers.[63] At the height of its existence the VOC had 25,000 employees who worked in Asia and 11,000 who were en route.[64] Also, while most of its shareholders were Dutch, about a quarter of the initial shareholders were Zuid-Nederlanders (people from an area that includes modern Belgium and Luxembourg) and there were also a few dozen Germans.[65]

The VOC had two types of shareholders: the participanten, who could be seen as non-managing members, and the 76 bewindhebbers (later reduced to 60) who acted as managing directors. This was the usual set-up for Dutch joint-stock companies at the time. The innovation in the case of the VOC was that the liability of not just the participanten but also of the bewindhebbers was limited to the paid-in capital (usually, bewindhebbers had unlimited liability). The VOC therefore was a limited liability company. Also, the capital would be permanent during the lifetime of the company. As a consequence, investors that wished to liquidate their interest in the interim could only do this by selling their share to others on the Amsterdam Stock Exchange.[66] Confusion of confusions, a 1688 dialogue by the Sephardi Jew Joseph de la Vega analysed the workings of this one-stock exchange.

The VOC consisted of six Chambers (Kamers) in port cities: Amsterdam, Delft, Rotterdam, Enkhuizen, Middelburg and Hoorn. Delegates of these chambers convened as the Heeren XVII (the Lords Seventeen). They were selected from the bewindhebber-class of shareholders.[67]

Of the Heeren XVII, eight delegates were from the Chamber of Amsterdam (one short of a majority on its own), four from the Chamber of Zeeland, and one from each of the smaller Chambers, while the seventeenth seat was alternatively from the Chamber of Middelburg-Zeeland or rotated among the five small Chambers. Amsterdam had thereby the decisive voice. The Zeelanders in particular had misgivings about this arrangement at the beginning. The fear was not unfounded, because in practice it meant Amsterdam stipulated what happened.

The six chambers raised the start-up capital of the Dutch East India Company:

| Chamber | Capital (Guilders) |

|---|---|

| Amsterdam | 3,679,915 |

| Middelburg | 1,300,405 |

| Enkhuizen | 540,000 |

| Delft | 469,400 |

| Hoorn | 266,868 |

| Rotterdam | 173,000 |

| Total: | 6,424,588 |

The raising of capital in Rotterdam did not go so smoothly. A considerable part originated from inhabitants of Dordrecht. Although it did not raise as much capital as Amsterdam or Middelburg-Zeeland, Enkhuizen had the largest input in the share capital of the VOC. Under the first 358 shareholders, there were many small entrepreneurs, who dared to take the risk. The minimum investment in the VOC was 3,000 guilders, which priced the Company's stock within the means of many merchants.[68]

Among the early shareholders of the VOC, immigrants played an important role. Under the 1,143 tenderers were 39 Germans and no fewer than 301 from the Southern Netherlands (roughly present Belgium and Luxembourg, then under Habsburg rule), of whom Isaac le Maire was the largest subscriber with ƒ85,000. VOC's total capitalisation was ten times that of its British rival.

The Heeren XVII (Lords Seventeen) met alternately 6 years in Amsterdam and 2 years in Middelburg-Zeeland. They defined the VOC's general policy and divided the tasks among the Chambers. The Chambers carried out all the necessary work, built their own ships and warehouses and traded the merchandise. The Heeren XVII sent the ships' masters off with extensive instructions on the route to be navigated, prevailing winds, currents, shoals and landmarks. The VOC also produced its own charts.

In the context of the Dutch-Portuguese War the company established its headquarters in Batavia, Java (now Jakarta, Indonesia). Other colonial outposts were also established in the East Indies, such as on the Maluku Islands, which include the Banda Islands, where the VOC forcibly maintained a monopoly over nutmeg and mace. Methods used to maintain the monopoly involved extortion and the violent suppression of the native population, including mass murder.[69] In addition, VOC representatives sometimes used the tactic of burning spice trees to force indigenous populations to grow other crops, thus artificially cutting the supply of spices like nutmeg and cloves.[70]

VOC outposts

Organization and leadership structures were varied as necessary in the various VOC outposts:

Opperhoofd is a Dutch word (pl. Opperhoofden), which literally means 'supreme chief'. In this VOC context, the word is a gubernatorial title, comparable to the English Chief factor, for the chief executive officer of a Dutch factory in the sense of trading post, as led by a factor, i.e. agent.

- See more at VOC Opperhoofden in Japan

Council of Justice in Batavia

The Council of Justice in Batavia was the appellate court for all the other VOC Company posts in the VOC empire.

Shareholder activism at the VOC and the beginnings of modern corporate governance

The seventeenth-century Dutch businessmen, especially the VOC investors, were possibly the history's first recorded investors to consider the corporate governance's problems.[71][72] Isaac Le Maire, who is known as history's first recorded short seller, was also a sizeable shareholder of the VOC. In 1609, he complained of the VOC's shoddy corporate governance. On 24 January 1609, Le Maire filed a petition against the VOC, marking the first recorded expression of shareholder activism. In what is the first recorded corporate governance dispute, Le Maire formally charged that the VOC's board of directors (the Heeren XVII) sought to "retain another’s money for longer or use it ways other than the latter wishes" and petitioned for the liquidation of the VOC in accordance with standard business practice.[73][74][75] Initially the largest single shareholder in the VOC and a bewindhebber sitting on the board of governors, Le Maire apparently attempted to divert the firm's profits to himself by undertaking 14 expeditions under his own accounts instead of those of the company. Since his large shareholdings were not accompanied by greater voting power, Le Maire was soon ousted by other governors in 1605 on charges of embezzlement, and was forced to sign an agreement not to compete with the VOC. Having retained stock in the company following this incident, in 1609 Le Maire would become the author of what is celebrated as "first recorded expression of shareholder advocacy at a publicly traded company".[76][77][78]

In 1622, the history's first recorded shareholder revolt also happened among the VOC investors who complained that the company account books had been "smeared with bacon" so that they might be "eaten by dogs." The investors demanded a "reeckeninge," a proper financial audit.[79] The 1622 campaign by the shareholders of the VOC is a testimony of genesis of corporate social responsibility (CSR) in which shareholders staged protests by distributing pamphlets and complaining about management self enrichment and secrecy.[80]

Main trading posts, settlements and colonies

Asia

Indonesia

Indian subcontinent

- Dutch Coromandel (1608–1825)

- Dutch Suratte (1616–1825)

- Dutch Bengal (1627–1825)

- Dutch Ceylon (1640–1796)

- Dutch Malabar (1661–1795)

Japan

- Hirado, Nagasaki (1609–1641)

- Dejima, Nagasaki (1641–1853)

Taiwan

- Anping (Fort Zeelandia)

- Tainan (Fort Provincia)

- Wang-an, Penghu, Pescadores Islands (Fort Vlissingen; 1620–1624)

- Keelung (Fort Noord-Holland, Fort Victoria)

- Tamsui (Fort Antonio)

Malaysia

- Dutch Malacca (1641–1795; 1818–1825)

Thailand

- Ayutthaya (1608–1767)

Vietnam

- Thǎng Long/Tonkin (1636–1699)

- Hội An (1636–1741)

Africa

Mauritius

- Dutch Mauritius (1638–1658; 1664–1710)

South Africa

- Dutch Cape Colony (1652–1806)

Main competitors

| Years | Company |

|---|---|

| 1581–1825 | Levant Company |

| 1600–1874 | British East India Company |

| 1616–1729 | Danish East India Company |

| 1621–1791 | Dutch West India Company |

| 1628–1633 | Portuguese East India Company |

| 1664–1794 | French East India Company |

| 1722–1734 | Ostend Company |

| 1731–1813 | Swedish East India Company |

| 1752–1757 | Emden Company |

Conflicts and wars involving the VOC

- Sino-Dutch conflicts (1620s–1662)

- Trịnh–Nguyễn War

- Dutch–Portuguese War

- Malayan–Portuguese War

- Sinhalese–Portuguese War

- Travancore–Dutch War

- Fourth Anglo-Dutch War

Historical roles and legacy

With regard to the VOC's importance in global corporate history, Australian journalist Hugh Edwards (1970) writes, "The Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie was the most powerful single commercial concern the world has ever known. General Motors, British Tobacco, Ford, The Shell Company, Mitsubishi, Standard Oil – any of the other giant holdings of today are on the level of village bootmakers compared with the might and power and influence once wielded by the VOC."[81][82] In his book Amsterdam: A History of the World's Most Liberal City (2013), Russell Shorto summarizes the VOC's greatness: "Like the oceans it mastered, the VOC had a scope that is hard to fathom. One could craft a defensible argument that no company in history has had such an impact on the world. Its surviving archives—in Cape Town, Colombo, Chennai, Jakarta, and The Hague—have been measured (by a consortium applying for a UNESCO grant to preserve them) in kilometers. In innumerable ways the VOC both expanded the world and brought its far-flung regions together. It introduced Europe to Asia and Africa, and vice versa (while its sister multinational, the West India Company, set New York City in motion and colonized Brazil and the Caribbean Islands). It pioneered globalization and invented what might be the first modern bureaucracy. It advanced cartography and shipbuilding. It fostered disease, slavery, and exploitation on a scale never before imaged."[10]

The company was arguably the first megacorporation the world has ever seen, possessing quasi-governmental powers, including the ability to wage war, imprison and execute convicts, negotiate treaties, coin money and establish colonies. Many economic and political historians consider the VOC as the most valuable, powerful and influential corporation in world history.[9][10][11]

The VOC existed for almost 200 years from its founding in 1602, when the States-General of the Netherlands granted it a 21-year monopoly over Dutch operations in Asia until its demise in 1796. During those two centuries (between 1602 and 1796), the VOC sent almost a million Europeans to work in the Asia trade on 4,785 ships, and netted for their efforts more than 2.5 million tons of Asian trade goods. By contrast, the rest of Europe combined sent only 882,412 people from 1500 to 1795, and the fleet of the English (later British) East India Company, the VOC's nearest competitor, was a distant second to its total traffic with 2,690 ships and a mere one-fifth the tonnage of goods carried by the VOC. The VOC enjoyed huge profits from its spice monopoly through most of the 17th century.[83]

The company was also considered by many to be the very first major and the greatest corporation in history.[note 6][85] The VOC's territories were even larger than some countries. By 1669, the VOC was the richest company the world had ever seen, with over 150 merchant ships, 40 warships, 50,000 employees, a private army of 10,000 soldiers, and a dividend payment of 40% on the original investment.[86][87][88]

Institutional innovations and contributions in business and financial history

The VOC played a crucial role in the rise of corporate-led globalization,[94] corporate governance, corporate identity,[95] corporate social responsibility, corporate finance, modern entrepreneurship, and financial capitalism.[96][97][11] During its golden age, the company made some fundamental institutional innovations in economic and financial history. These financially revolutionary innovations allowed a single company (like the VOC) to mobilize financial resources from a large number of investors and create ventures at a scale that had previously only been possible for monarchs.[98] In the words of Canadian historian and sinologist Timothy Brook, "the Dutch East India Company—the VOC, as it is known—is to corporate capitalism what Benjamin Franklin's kite is to electronics: the beginning of something momentous that could not have been predicted at the time."[9] The birth of the VOC is often considered to be the official beginning of the corporate globalization era with the rise of modern corporations as a powerful socio-politico-economic system that significantly affect humans lives in every corner of the world today.[99][9][100] As the world's first publicly traded company and first listed company (the first company to be ever listed on an official stock exchange), the VOC was the first company to issue stock and bonds to the general public. Considered by many experts to be the world's first truly (modern) multinational corporation,[101] the VOC was also the first permanently organized limited-liability joint-stock company, with a permanent capital base.[note 7][103] The VOC shareholders were the pioneers in laying the basis for modern corporate governance and corporate finance. The VOC is often considered as the precursor of modern corporations, if not the first truly modern corporation.[104] It was the VOC that invented the idea of investing in the company rather than in a specific venture governed by the company. With its pioneering features such as corporate identity (first globally-recognized corporate logo), entrepreneurial spirit, legal personhood, transnational (multinational) operational structure, high and stable profitability, permanent capital (fixed capital stock),[105][106] freely transferable shares and tradable securities, separation of ownership and management, and limited liability for both shareholders and managers, the VOC is generally considered a major institutional breakthrough[107] and the model for the large-scale business enterprises that now dominate the global economy.[108]

The VOC was the driving force behind the rise of Amsterdam as the first modern model of (global) international financial centres[note 8] that now dominate the global financial system. During the 17th century and most of the 18th century, Amsterdam had been the most influential and powerful financial centre of the world.[110][111][112][113][114] The VOC also played a major role in the creation of the world's first fully functioning financial market,[115] with the birth of a fully fledged capital market.[116] The Dutch were also the first who effectively used a fully-fledged capital market (including the bond market and the stock market) to finance companies (such as the VOC and the WIC). It was in the 17th-century Dutch Republic that the global securities market began to take on its modern form. And it was in Amsterdam that the important institutional innovations such as publicly traded companies, transnational corporations, capital markets (including bond markets and stock markets), central banking system, investment banking system, and investment funds (mutual funds) were systematically operated for the first time in history. In 1602 the VOC established an exchange in Amsterdam where VOC stock and bonds could be traded in a secondary market. The VOC undertook the world's first recorded IPO in the same year. The Amsterdam Stock Exchange (Amsterdamsche Beurs or Beurs van Hendrick de Keyser in Dutch) was also the world's first fully-fledged stock exchange. While the Italian city-states produced the first transferable government bonds, they didn't develop the other ingredient necessary to produce a fully fledged capital market: corporate shareholders. The Dutch East India Company (VOC) became the first company to offer shares of stock. The dividend averaged around 18% of capital over the course of the company's 200-year existence. The launch of the Amsterdam Stock Exchange by the VOC in the early 1600s, has long been recognized as the origin of 'modern' stock exchanges that specialize in creating and sustaining secondary markets in the securities (such as bonds and shares of stock) issued by corporations.[117] Dutch investors were the first to trade their shares at a regular stock exchange. The process of buying and selling these shares of stock in the VOC became the basis of the first official (formal) stock market in history.[118][89][119] It was in the Dutch Republic that the early techniques of stock-market manipulation were developed. The Dutch pioneered stock futures, stock options, short selling, bear raids, debt-equity swaps, and other speculative instruments.[120] Amsterdam businessman Joseph de la Vega's Confusion of Confusions (1688) was the earliest book about stock trading.

Impacts on economic and social history of the Netherlands

The VOC was a major force behind the financial revolution[note 9][123][124] and economic miracle[125][126][127] of the Dutch Republic in the 17th-century. During their Golden Age, the Dutch Republic (or the Northern Netherlands), as the resource-poor and obscure cousins of the more urbanized Southern Netherlands, rose to become the world's leading economic and financial superpower.[note 10][130][131][132][133][134] The VOC's shipyards also contributed greatly to the Dutch domination of global shipbuilding and shipping industries during the 1600s.[note 11] "By seventeenth century standards," as Richard Unger affirms, Dutch shipbuilding "was a massive industry and larger than any shipbuilding industry which had preceded it."[137] By the 1670s the size of the Dutch merchant fleet probably exceeded the combined fleets of England, France, Spain, Portugal, and Germany.[138] Until the mid-1700s, the economic system of the Dutch Republic (including its financial system) was the most advanced and sophisticated ever seen in history.[139] However, in a typical multicultural society of the Netherlands, the VOC's history (and especially its dark side) has always been a potential source of controversy. In 2006 when the Dutch Prime Minister Jan Pieter Balkenende referred to the pioneering entrepreneurial spirit and work ethics of the Dutch people and Dutch Republic in their Golden Age, he coined the term "VOC mentality" (VOC-mentaliteit in Dutch).[note 12] It unleashed a wave of criticism, since such romantic views about the Dutch Golden Age ignores the inherent historical associations with colonialism, exploitation and violence. Balkenende later stressed that "it had not been his intention to refer to that at all".[141] But in spite of criticisms, the "VOC-mentality", as a characteristic of the selective historical perspective on the Dutch Golden Age, has been considered a key feature of Dutch cultural policy for many years.[141]

Influences on Dutch Golden Age art

From 1609 the VOC had a trading post in Japan (Hirado, Nagasaki), which used local paper for its own administration. However, the paper was also traded to the VOC's other trading posts and even the Dutch Republic. Many impressions of the Dutch Golden Age artist Rembrandt's prints were done on Japanese paper. From about 1647 Rembrandt sought increasingly to introduce variation into his prints by using different sorts of paper, and printed most of his plates regularly on Japanese paper. He also used the paper for his drawings. The Japanese paper types – which was actually imported from Japan by the VOC – attracted Rembrandt with its warm, yellowish colour.[142] They are often smooth and shiny, whilst Western paper has a more rough and matt surface.[143] Moreover, the VOC's imported Chinese porcelain wares are often depicted in many Dutch Golden Age genre paintings, especially in Jan Vermeer's paintings.[9]

VOC world as a knowledge network in the Dutch maritime world-system

During the Dutch Golden Age, the Dutch – using their expertise in doing business, cartography, shipbuilding, seafaring and navigation – traveled to the far corners of the world, leaving their language embedded in the names of many places. Dutch exploratory voyages revealed largely unknown landmasses to the civilized world and put their names on the world map. The Dutch came to dominate the map making and map printing industry by virtue of their own travels, trade ventures, and widespread commercial networks.[144] As Dutch ships reached into the unknown corners of the globe, Dutch cartographers incorporated new geographical discoveries into their work. Instead of using the information themselves secretly, they published it, so the maps multiplied freely. For almost 200 years, the Dutch dominated world trade.[145] Dutch ships carried goods, but they also opened up opportunities for the exchange of knowledge.[146] The commercial networks of the Dutch transnational companies, i.e. the VOC and West India Company (WIC/GWIC), provided an infrastructure which was accessible to people with a scholarly interest in the exotic world.[147][148][149][150][151] The VOC's bookkeeper Hendrick Hamel was the first known European/Westerner to experience first-hand and write about Joseon-era Korea.[note 13] In his report (published in the Dutch Republic) in 1666 Hendrick Hamel described his adventures on the Korean Peninsula and gave the first accurate description of daily life of Koreans to the western world.[152][153][154] The VOC trade post on Dejima, an artificial island off the coast of Nagasaki, was for more than two hundred years the only place where Europeans were permitted to trade with Japan. Rangaku (literally 'Dutch Learning', and by extension 'Western Learning') is a body of knowledge developed by Japan through its contacts with the Dutch enclave of Dejima, which allowed Japan to keep abreast of Western technology and medicine in the period when the country was closed to foreigners, 1641–1853, because of the Tokugawa shogunate's policy of national isolation (sakoku).

Roles in the global economy and international relations

.jpg)

Considered by many political and economic historians as an autonomous quasi-state within another state,[note 14][157] the VOC, for almost 200 years of its existence, was a key (non-state) player in Asia-related trade and politics. More than just a pure multinational trading company, the VOC – although privately financed – was the international arm of the Dutch Republic government. The company was much an unofficial representative of the States General of the United Provinces in foreign relations of the Dutch Republic with many states, especially Dutch-Asian relations.

The VOC had seminal influences on the history of some countries and territories such as New York (New Netherland),[158] Indonesia, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Taiwan and Japan.[159]

Contributions in the Age of Exploration

More information: Maritime history of the Dutch East India Company; Dutch Republic in the Age of Discovery; Cartography in the Dutch Republic; Golden Age of Dutch cartography / Golden Age of Netherlandish cartography

The Dutch East India Company (VOC) was also a major force behind the Golden Age of Dutch exploration and discovery (ca. 1590s–1720s). The VOC-funded exploratory voyages such as those led by Willem Janszoon (Duyfken), Henry Hudson (Halve Maen) and Abel Tasman revealed largely unknown landmasses to the civilized world. Also, in the Golden Age of Netherlandish cartography[note 15] (ca. 1570s–1670s), the VOC's navigators and cartographers[note 16] helped shape modern geographical and cartographic (like world map) knowledge as we know them today.

Halve Maen's exploratory voyage and role in the formation of New Netherland

In 1609, English sea captain and explorer Henry Hudson was hired by the VOC émigrés running the VOC located in Amsterdam[160] to find a north-east passage to Asia, sailing around Scandinavia and Russia. He was turned back by the ice of the Arctic in his second attempt, so he sailed west to seek a north-west passage rather than return home. He ended up exploring the waters off the east coast of North America aboard the vlieboot Halve Maen. His first landfall was at Newfoundland and the second at Cape Cod.

Hudson believed that the passage to the Pacific Ocean was between the St. Lawrence River and Chesapeake Bay, so he sailed south to the Bay then turned northward, traveling close along the shore. He first discovered Delaware Bay and began to sail upriver looking for the passage. This effort was foiled by sandy shoals, and the Halve Maen continued north. After passing Sandy Hook, Hudson and his crew entered the narrows into the Upper New York Bay. (Unbeknownst to Hudson, the narrows had already been discovered in 1524 by explorer Giovanni da Verrazzano; today, the bridge spanning them is named after him.[161]) Hudson believed that he had found the continental water route, so he sailed up the major river which later bore his name: the Hudson. He found the water too shallow to proceed several days later, at the site of present-day Troy, New York.[162]

Upon returning to the Netherlands, Hudson reported that he had found a fertile land and an amicable people willing to engage his crew in small-scale bartering of furs, trinkets, clothes, and small manufactured goods. His report was first published in 1611 by Emanuel Van Meteren, an Antwerp émigré and the Dutch Consul at London.[160] This stimulated interest[163] in exploiting this new trade resource, and it was the catalyst for Dutch merchant-traders to fund more expeditions.

In 1611–12, the Admiralty of Amsterdam sent two covert expeditions to find a passage to China with the yachts Craen and Vos, captained by Jan Cornelisz Mey and Symon Willemsz Cat, respectively. In four voyages made between 1611 and 1614, the area between present-day Maryland and Massachusetts was explored, surveyed, and charted by Adriaen Block, Hendrick Christiaensen, and Cornelius Jacobsen Mey. The results of these explorations, surveys, and charts made from 1609 through 1614 were consolidated in Block's map, which used the name New Netherland for the first time.

Dutch exploration and mapping of Australia and Oceania

In terms of world history of geography and exploration, the VOC can be credited with putting most of Australia's coast (then Hollandia Nova and other names) on the world map, between 1606 and 1756.[164] While Australia's territory (originally known as New Holland) never became an actual Dutch settlement or colony,[165] Dutch navigators were the first to undisputedly explore and map Australian coastline. In the 17th century, the VOC's navigators and explorers charted almost three-quarters of Australia's coastline, except its east coast. The Dutch ship, Duyfken, led by Willem Janszoon, made the first documented European landing in Australia in 1606.[166] Although a theory of Portuguese discovery in the 1520s exists, it lacks definitive evidence.[167][168][169] Precedence of discovery has also been claimed for China,[170] France,[171] Spain,[172] India,[173] and even Phoenicia.[174]

Hendrik Brouwer's discovery of the Brouwer Route, that sailing east from the Cape of Good Hope until land was sighted and then sailing north along the west coast of Australia was a much quicker route than around the coast of the Indian Ocean, made Dutch landfalls on the west coast inevitable. The first such landfall was in 1616, when Dirk Hartog landed at Cape Inscription on what is now known as Dirk Hartog Island, off the coast of Western Australia, and left behind an inscription on a pewter plate. In 1697 the Dutch captain Willem de Vlamingh landed on the island and discovered Hartog's plate. He replaced it with one of his own, which included a copy of Hartog's inscription, and took the original plate home to Amsterdam, where it is still kept in the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

In 1627, the VOC's explorers François Thijssen and Pieter Nuyts discovered the south coast of Australia and charted about 1,800 kilometres (1,100 mi) of it between Cape Leeuwin and the Nuyts Archipelago.[175][176] François Thijssen, captain of the ship 't Gulden Zeepaert (The Golden Seahorse), sailed to the east as far as Ceduna in South Australia. The first known ship to have visited the area is the Leeuwin ("Lioness"), a Dutch vessel that charted some of the nearby coastline in 1622. The log of the Leeuwin has been lost, so very little is known of the voyage. However, the land discovered by the Leeuwin was recorded on a 1627 map by Hessel Gerritsz: Caert van't Landt van d'Eendracht ("Chart of the Land of Eendracht"), which appears to show the coast between present-day Hamelin Bay and Point D’Entrecasteaux. Part of Thijssen's map shows the islands St Francis and St Peter, now known collectively with their respective groups as the Nuyts Archipelago. Thijssen's observations were included as soon as 1628 by the VOC cartographer Hessel Gerritsz in a chart of the Indies and New Holland. This voyage defined most of the southern coast of Australia and discouraged the notion that "New Holland" as it was then known, was linked to Antarctica.

In 1642, Abel Tasman sailed from Mauritius and on 24 November, sighted Tasmania. He named Tasmania Anthoonij van Diemenslandt (Anglicised as Van Diemen's Land), after Anthony van Diemen, the VOC's Governor General, who had commissioned his voyage.[177][178][179] It was officially renamed Tasmania in honour of its first European discoverer on 1 January 1856.[180]

In 1642, during the same expedition, Tasman's crew discovered and charted New Zealand's coastline. They were the first Europeans known to reach New Zealand. Tasman anchored at the northern end of the South Island in Golden Bay (he named it Murderers' Bay) in December 1642 and sailed northward to Tonga following a clash with local Māori. Tasman sketched sections of the two main islands' west coasts. Tasman called them Staten Landt, after the States General of the Netherlands, and that name appeared on his first maps of the country. In 1645 Dutch cartographers changed the name to Nova Zeelandia in Latin, from Nieuw Zeeland, after the Dutch province of Zeeland. It was subsequently Anglicised as New Zealand by James Cook. Various claims have been made that New Zealand was reached by other non-Polynesian voyagers before Tasman, but these are not widely accepted.

Criticisms

In spite of the VOC's historical successes and contributions, the company has long been criticized for its quasi-absolute commercial monopoly, colonialism, exploitation (including use of slave labour), slave trade, use of violence, environmental destruction (including deforestation), and overly bureaucratic in organizational structure.[10]

Cultural depictions of people and things associated with the VOC

- Batavia: a shipwreck on the Houtman Abrolhos in 1629, made famous by the subsequent mutiny and massacre that took place among the survivors. [see also Batavia (opera)]

- Flying Dutchman: a legendary ghost ship in several maritime myths, likely to have originated from the 17th-century golden age of the VOC.

- Hansken: a female Asian elephant from Dutch Ceylon. The young elephant Hansken was brought to Amsterdam in 1637, aboard a VOC ship. Dutch Golden Age artist Rembrandt made some historical drawings of Hansken.

- Batavia, Dutch East Indies: 1650s/1660s paintings of scenes from everyday life by Dutch Golden Age painter Andries Beeckman, one of the few painters who travelled to the Dutch East Indies in the 17th-century.

- Cosmos: A Personal Voyage: in the 6th episode Travellers' Tales of the popular documentary TV series Cosmos (1980), American astronomer Carl Sagan, who also served as host, took a look at the voyage to Jupiter and Saturn, and compared these events with the adventuring spirit of the Dutch Golden Age explorers (including the VOC's navigators).

- The Sino-Dutch War 1661: 2000 Chinese historical drama film. The film is loosely based on the life of Koxinga (Zheng Chenggong) and focuses on his battle with the VOC for control of Dutch Formosa at the Siege of Fort Zeelandia.

- Ocean's Twelve: a 2004 American comedy heist film inspired by the historical story from the VOC's IPO and the first shares of stock ever traded publicly in history. The VOC's stock certificate is the focused heist by the burglars in the movie.

- The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet, 2010 historical novel by British author David Mitchell.

- My Father's Islands: Abel Tasman's Heroic Voyages: a 2012 juvenile fiction by Christobel Mattingley, written from the perspective of Tasman's young daughter, Claesgen. The fictional story was inspired by a 1637 painting of the Tasman family by the Dutch Golden Age painter Jacob Gerritsz. Cuyp, one of the treasures of the National Library of Australia.

- The Tsar-Carpenter: a cultural depiction of Tsar Peter the Great (Peter I of Russia) in his undercover visit to the Dutch Republic as part of the Grand Embassy mission (1697–1698). When Peter the Great wanted to learn more about the Dutch Republic's sea power,[181][182] he came to study seamanship, shipbuilding industry and carpentry in Amsterdam and Zaandam (Saardam).[note 17] Through the agency of Nicolaas Witsen, mayor of Amsterdam and an expert on Russia, Tsar Peter I worked as a ship's carpenter in the VOC's shipyards in Holland. [see also Zar und Zimmermann (opera) and The Czar and the Carpenter (film)]

- Megacorporation or mega-corporation: a quasi-fictional term/concept derived from the combination of the prefix mega- with the word corporation, possibly inspired by the VOC's history. It refers to a (quasi-fictional) corporation that is a massive conglomerate, possessing quasi-governmental powers and holding monopolistic control over markets.

- Black swan theory: a metaphor or metatheory of science popularized by Nassim Nicholas Taleb. It was possibly inspired by Willem de Vlamingh's 1697 discovery. De Vlamingh was the first known European/Western to observe and describe black swans and quokkas, in Western Australia.

Non-fiction works relating to the history of the VOC

- Islands of Angry Ghosts: Murder, Mayhem and Mutiny: The Story of the Batavia, 1966 book by Hugh Edwards.

- Batavia's Graveyard: The True Story of the Mad Heretic Who Led History's Bloodiest Mutiny, 2002 book by Mike Dash.

- Vermeer's Hat: The Seventeenth Century and the Dawn of the Global World, 2008 book by Timothy Brook.

- The Ascent of Money: A Financial History of the World, 2008 book and an adapted television documentary by Niall Ferguson.

Places and things named after the VOC and its people

For the full list of places explored, mapped, and named by people of the VOC, see List of place names of Dutch origin.

- Dutch East India Company (VOC): 10649 VOC (minor planet)

- Willem Blaeu: 10652 Blaeu (minor planet)

- Willem Bontekoe: 10654 Bontekoe (minor planet)

- Hendrik Brouwer: Brouwer Route

- Pieter de Carpentier: Gulf of Carpentaria

- Jan Carstenszoon: Mount Carstensz; Carstensz Pyramid; Carstensz Glacier

- Jan Pieterszoon Coen: Coen River

- Anthony van Diemen: Anthoonij van Diemenslandt (Van Diemen's Land); Van Diemen Gulf

- Maria van Diemen:[note 18] Maria Island

- Hendrik Adriaan van Rheede tot Drakenstein: Drakenstein (mountain ranges); Drakenstein (local municipality)

- Cornelis Jacob van de Graaff: Graaff-Reinet[note 19]

- Dirk Hartog: Dirk Hartog Island; Hartog Plate

- Wiebbe Hayes: Wiebbe Hayes Stone Fort

- Frederick de Houtman: Houtman Abrolhos; 10650 Houtman (minor planet)

- Henry Hudson: Hudson River; Hudson Valley

- Joan Maetsuycker: Maatsuyker Islands; Maatsuyker Island

- Pieter Nuyts: Nuyts Archipelago; Nuyts Land District; Nuytsia

- Francisco Pelsaert: Pelsaert Island; Pelsaert Group

- Petrus Plancius: Planciusdalen; Planciusbukta; 10648 Plancius (minor planet)

- Jan van Riebeeck: Riebeeckstad; Riebeek-Kasteel; Riebeeckosaurus

- Joost Schouten: Schouten Island

- Simon van der Stel: Simonstad (Simon's Town); Stellenbosch; Stellenbosch University

- Hendrik Swellengrebel: Swellendam

- Salomon Sweers: Sweers Island

- Abel Tasman: Tasmania; Tasman Sea; Tasmanian devil (see also List of things named after Abel Tasman)

- Maarten Gerritsz Vries: Vries Strait

- Nicolaes Witsen: 10653 Witsen (minor planet)

VOC's important heritage sites

- Netherlands: Amsterdam (Oost-Indisch Huis); Zaandam

- Indonesia: Java (Jakarta)

- South Africa: Western Cape (Cape Town; Stellenbosch; Swellendam; Franschhoek; Paarl)

- Taiwan: Tainan (Fort Zeelandia)

- Japan: Nagasaki (Hirado & Dejima)

- Malaysia: Malacca (Christ Church & Stadthuys)

- Australia: Western Australia (Dirk Hartog Island & Houtman Abrolhos)

Populated places established by people of the VOC

Populated places (including cities, towns and villages) established/founded[note 20] by people of the Dutch East India Company (VOC).

- Batavia (Dutch East Indies), modern-day Jakarta

- Tainan, the oldest urban area in Taiwan

- Kaapstad (Cape Town), the oldest urban area in South Africa and one of the first permanent European settlements in Sub-Saharan Africa. Constantia (Cape Town's suburb) is considered one of the oldest wine-producing regions in the Southern Hemisphere.

- Stellenbosch, the second oldest urban area (town) in South Africa

- Swellendam, the third oldest urban area (town) in South Africa

- Graaff-Reinet, the fourth oldest urban area (town) in South Africa

- Franschhoek, a town in the Western Cape Province, South Africa

- Paarl, the third oldest European settlement in South Africa and the largest town in the Cape Winelands

- Simonstad (Simon's Town), a town near Cape Town, South Africa

- Dutch Mauritius, the first permanent human settlement ever in Mauritius[note 21]

VOC scholars

Some of the notable VOC scholars including Charles Ralph Boxer, Leonard Blussé, Warwick Funnell, Femme Gaastra, Oscar Gelderblom, Joost Jonker, Om Prakash, Jeffrey Robertson, and Günter Schilder.

VOC archives and records

The VOC's operations (trading posts and colonies) produced not only warehouses packed with spices, coffee, tea, textiles, porcelain and silk, but also shiploads of documents. Data on political, economic, cultural, religious, and social conditions spread over an enormous area circulated between the VOC establishments, the administrative centre of the trade in Batavia (modern-day Jakarta), and the board of directors (the Heeren XVII/Gentlemen Seventeen) in the Dutch Republic.[183] The VOC records are included in UNESCO's Memory of the World Register.[184]

VOC coins

Notable VOC ships

- Replicas have been constructed of several VOC ships, marked with an (R)

- Akerendam

- Amsterdam (R)

- Arnhem

- Batavia (R)

- Braek

- Concordia

- Dromedaris ("Dromedary camel")

- Duyfken ("Little Dove") (R)

- Eendracht (1615) ("Unity")

- Galias

- Grooten Broeck ("Great Stream")

- Goede Hoop ("Good Hope")

- Gulden Zeepaert ("Golden Seahorse")

- Halve Maen ("Half moon") (R)

- Haerlem[185][186]

- Hoogkarspel

- Heemskerck

- Hollandia

- Klein Amsterdam ("Small Amsterdam")

- Landskroon

- Leeuwerik ("Lark")

- Leyden

- Limmen

- Mauritius

- Meermin ("Mermaid")

- Naerden

- Nieuw Hoorn ("New Hoorn")

- Oliphant ("Elephant")

- Pera ("Perak", Malay for "silver")

- Prins Willem ("Prince William") (R)

- Reijger

- Ridderschap van Holland ("Knighthood of Holland")

- Rooswijk

- Sardam

- Texel

- Utrecht

- Vergulde Draeck ("Gilded Dragon")

- Vianen

- Vliegende Hollander ("Flying Dutchman")

- Vliegende Swaan ("Flying Swan")

- Walvisch ("Whale")

- Wapen van Hoorn ("Arms of Hoorn")

- Wezel ("Weasel")

- Zeehaen ("Sea Cock")

- Zeemeeuw ("Seagull")

- Zeewijk

- Zuytdorp ("South Village")

VOC timeline and the firsts in history

- 1600s: The VOC's navigators became the first non-natives to undisputedly discover, explore and map coastlines of the Australian continent (including Mainland Australia, Tasmania, and their surrounding islands), New Zealand, Tonga, and Fiji.

- 1602: On March 20, the Dutch East India Company (VOC), the world's first true transnational corporation, was originally established as a chartered company. The VOC was the first joint-stock company to get a fixed capital stock and the first recorded (public) company ever to pay regular dividends.

- 1606: The first (undisputed) documented European sighting of and landing on the Australian continent (Nova Hollandia) by the VOC navigator Willem Janszoon aboard the Duyfken.

- 1609: The VOC ship Halve Maen's exploratory voyage, a milestone in the history of New York (including New York City) and North America.

- 1609: Dutch jurist Hugo Grotius wrote Mare Liberum, a foundational treatise on modern international law of the sea, while being a counsel to the Dutch East India Company (VOC) over the seizing of the Santa Catarina Portuguese carrack issue.

- 1609: The first recorded corporate governance dispute, took place on January 24 (1609) between the shareholders/investors (most notably Isaac Le Maire) and directors of the VOC.[187]

- 1609: The first recorded short seller in history, Isaac Le Maire, a sizeable shareholder of the VOC.

- 1610: An early mechanism of financial regulation practice was the first recorded ban on short selling, by the Dutch authorities.

- 1611: The world's first official (formal) stock exchange and stock market were launched by the VOC in Amsterdam.

- 1611: The VOC was the first corporation to be ever actually listed on an official (formal) stock exchange. In other words, the VOC was the world's first formally listed public company (or publicly listed company).

- 1611: Discovery of the Brouwer route by the VOC navigator Hendrik Brouwer.

- 1616: The VOC navigator Dirk Hartog made the first recorded European landing on the west coast of the Australian continent.

- 1616: Hartog Plate, the first known European artefact found on Australian soil (Dirk Hartog Island).

- 1621: Establishment of the Dutch West India Company (WIC/GWIC).

- 1622: On January 24, Amsterdam-based businessman Isaac Le Maire filed a petition against the VOC, marking the first recorded expression of shareholder activism or shareholder rebellion.

- 1624–1662: Tainan (Dutch Formosa), the first urban area to be established in Taiwan.

- 1627: The VOC explorers François Thijssen and Pieter Nuyts made the first recorded European landing on the south coast of the Australian continent and charted about 1,800 kilometres of it between Cape Leeuwin and the Nuyts Archipelago.

- 1629: Wiebbe Hayes Stone Fort (West Wallabi Island), the first known European structure to be built on the Australian continent.

- 1636–1637: Tulip Mania, generally considered to be the first recorded economic bubble (or speculative bubble) in history.

- 1638–1710: Dutch Mauritius, the first permanent human settlement to be established in Mauritius.

- 1641–1853: Beginnings of Rangaku (first phase: 1641–1720). After 1641, the VOC businessmen were the only Western allowed to trade with or to enter isolated Japan.

- 1642: The VOC explorer Abel Tasman discovered, explored, and charted Tasmania and its neighboring islands. He named Tasmania Anthoonij van Diemenslandt (Anglicised as Van Diemen's Land), after Anthony van Diemen, the Dutch East India Company's Governor General, who had commissioned his voyage.

- 1642: On December 13, Abel Tasman's VOC crew were the first non-natives known to discover, explore and chart New Zealand's coastline (Nova Zeelandia).

- 1652–1806: Kaapstad (Cape Town), the first urban area to be established in South Africa.

- 1653–1666: The VOC bookkeeper Hendrick Hamel was the first known non-Asian to experience first-hand and write about Joseon-era Korea (often referred to as the "Hermit Kingdom").

- 1659: Beginnings of the South African wine industry.

- 1688–1689: The first large-scale emigration of Huguenots to the Dutch Cape Colony (modern-day Western Cape, South Africa).

- 1697: European discovery of black swans for the first time in history, by the VOC navigator Willem de Vlamingh.