Hepatocellular carcinoma

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | |

|---|---|

| |

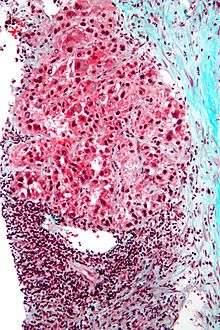

| Hepatocellular carcinoma in an individual who was hepatitis C positive. Autopsy specimen. | |

| Specialty | Oncology |

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most common type of primary liver cancer in adults, and is the most common cause of death in people with cirrhosis.[1]

It occurs in the setting of chronic liver inflammation, and is most closely linked to chronic viral hepatitis infection (hepatitis B or C) or exposure to toxins such as alcohol or aflatoxin. Certain diseases, such as hemochromatosis and alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency, markedly increase the risk of developing HCC. Metabolic syndrome and NASH are also increasingly recognized as risk factors for HCC.[2]

As with any cancer, the treatment and prognosis of HCC vary depending on the specifics of tumor histology, size, how far the cancer has spread, and overall health.

The vast majority of HCC occurs in Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, in countries where hepatitis B infection is endemic and many are infected from birth. The incidence of HCC in the United States and other developing countries is increasing due to an increase in hepatitis C virus infections. It is more common in male than females for unknown reasons.[2]

Signs and symptoms

Most cases of HCC occur in people who already have symptoms of chronic liver disease. They may present either with worsening of symptoms or may be without symptoms at the time of cancer detection. HCC may directly present with yellow skin, abdominal swelling due to fluid in the abdomen, easy bruising from blood clotting abnormalities, loss of appetite, unintentional weight loss, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, or feeling tired.[3]

Risk factors

HCC mostly occurs in people with cirrhosis of the liver, and so risk factors generally include factors which cause chronic liver disease that may lead to cirrhosis. Still, certain risk factors are much more highly associated with HCC than others. For example, while heavy alcohol consumption is estimated to cause 60-70% of cirrhosis, the vast majority of HCC occurs in cirrhosis attributed to viral hepatitis (although there may be overlap).[4] Recognized risk factors include:

- Chronic viral hepatitis (estimated cause of 80% cases globally)

- Chronic hepatitis B (approximately 50% cases)

- Chronic hepatitis C (approximately 25% cases)[5]

- Toxins:

- Alcohol abuse: the most common cause of cirrhosis[4]

- Aflatoxin

- Iron overload state (Hemochromatosis)

- Metabolic:

- Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: up to 20% progress to cirrhosis [6]

- Type 2 diabetes (probably aided by obesity)[7]

- Congenital disorders:

- Alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency

- Wilson's disease (controversial; while some theorise the risk increases,[8] case studies are rare[9] and suggest the opposite where Wilson's disease actually may confer protection[10])

- Hemophilia, although statistically associated with higher risk of HCC,[11] this is due to coincident chronic viral hepatitis infection related to repeated blood transfusions over lifetime.[12]

The significance of these risk factors varies globally. In regions where hepatitis B infection is endemic, such as southeast China, this is the predominant cause.[13] In populations largely protected by hepatitis B vaccination, such as the United States, HCC is most often linked to causes of cirrhosis such as chronic hepatitis C, obesity, and alcohol abuse.

Certain benign liver tumors, such as hepatocellular adenoma, may sometimes be associated with coexisting malignant HCC. There is limited evidence for the true incidence of malignancy associated with benign adenomas; however, the size of hepatic adenoma is considered to correspond to risk of malignancy and so larger tumors may be surgically removed. Certain subtypes of adenoma, particularly those with β-catenin activation mutation, are particularly associated with increased risk of HCC.

Children and adolescents are unlikely to have chronic liver disease, however, if they suffer from congenital liver disorders, this fact increases the chance of developing hepatocellular carcinoma.[14] Specifically, children with biliary atresia, infantile cholestasis, glycogen-storage diseases, and other cirrhotic diseases of the liver are predisposed to developing HCC in childhood.

Young adults afflicted by the rare fibrolamellar variant of hepatocellular carcinoma may have none of the typical risk factors, i.e. cirrhosis and hepatitis.

Diabetes mellitus

The risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in type 2 diabetics is greater (from 2.5[7] to 7.1[15] times the non diabetic risk) depending on the duration of diabetes and treatment protocol. A suspected contributor to this increased risk is circulating insulin concentration such that diabetics with poor insulin control or on treatments that elevate their insulin output (both states that contribute to a higher circulating insulin concentration) show far greater risk of hepatocellular carcinoma than diabetics on treatments that reduce circulating insulin concentration.[7][15][16][17] On this note, some diabetics who engage in tight insulin control (by keeping it from being elevated) show risk levels low enough to be indistinguishable from the general population.[15][16] This phenomenon is thus not isolated to diabetes mellitus type 2 since poor insulin regulation is also found in other conditions such as metabolic syndrome (specifically, when evidence of non alcoholic fatty liver disease or NAFLD is present) and again there is evidence of greater risk here too.[18][19] While there are claims that anabolic steroid abusers are at greater risk[20] (theorized to be due to insulin and IGF exacerbation[21][22]), the only evidence that has been confirmed is that anabolic steroid users are more likely to have hepatocellular adenomas (a benign form of HCC) transform into the more dangerous hepatocellular carcinoma.[23][24]

Pathogenesis

Hepatocellular carcinoma, like any other cancer, develops when there is a mutation to the cellular machinery that causes the cell to replicate at a higher rate and/or results in the cell avoiding apoptosis. In particular, chronic infections of hepatitis B and/or C can aid the development of hepatocellular carcinoma by repeatedly causing the body's own immune system to attack the liver cells, some of which are infected by the virus, others merely bystanders.[25] While this constant cycle of damage followed by repair can lead to mistakes during repair which in turn lead to carcinogenesis, this hypothesis is more applicable, at present, to hepatitis C. Chronic hepatitis C causes HCC through the stage of cirrhosis. In chronic hepatitis B, however, the integration of the viral genome into infected cells can directly induce a non-cirrhotic liver to develop HCC. Alternatively, repeated consumption of large amounts of ethanol can have a similar effect. The toxin aflatoxin from certain Aspergillus species of fungus is a carcinogen and aids carcinogenesis of hepatocellular cancer by building up in the liver. The combined high prevalence of rates of aflatoxin and hepatitis B in settings like China and West Africa has led to relatively high rates of hepatocellular carcinoma in these regions. Other viral hepatitides such as hepatitis A have no potential to become a chronic infection and thus are not related to hepatocellular carcinoma.

Diagnosis

Methods of diagnosis in HCC have evolved with the improvement in medical imaging. The evaluation of both asymptomatic patients and those with symptoms of liver disease involves blood testing and imaging evaluation. Although historically a biopsy of the tumor was required to prove the diagnosis, imaging (especially MRI) findings may be conclusive enough to obviate histopathologic confirmation.

Screening

Due to the fact that HCC most commonly occurs in the setting of chronic liver disease (e.g. viral hepatitis) and cirrhosis (about 80%), screening by ultrasound (US) is commonly advocated in this population. Surveillance recommendations vary, but the American Association of Liver Diseases recommends screening Asian men over the age of 40, Asian women over the age of 50, people with HBV and cirrhosis, and African and North American blacks. These people are screened with ultrasound every 6 months. Additional evaluation may include measurement of blood levels of AFP, which is a tumor marker. Elevated levels of AFP are associated with active HCC disease. At levels >20 sensitivity is 41-65% and specificity is 80-94%. However, at levels >200 sensitivity is 31, specificity is 99%.[26]

Ultrasound (US) is often the first imaging and screening modality used. On US, HCC often appears as a small hypoechoic lesion with poorly defined margins and coarse irregular internal echoes. When the tumor grows, it can sometimes appear heterogeneous with fibrosis, fatty change, and calcifications. This heterogeneity can look similar to cirrhosis and the surrounding liver parenchyma. A systematic review found that the sensitivity was 60 percent (95% CI 44-76%) and specificity was 97 percent (95% CI 95-98%) compared with pathologic examination of an explanted or resected liver as the reference standard. The sensitivity increases to 79% with AFP correlation.[27]

Higher risk people

In a person where there is higher suspicion of HCC, such as a person with symptoms or abnormal blood tests (i.e. alpha-fetoprotein and des-gamma carboxyprothrombin levels),[28] evaluation requires imaging of the liver by CT or MRI scans. Optimally, these scans are performed with intravenous contrast in multiple phases of hepatic perfusion in order to improve detection and accurate classification of any liver lesions by the interpreting radiologist. Due to the characteristic blood flow pattern of HCC tumors, a specific perfusion pattern of any detected liver lesion may conclusively detect an HCC tumor. Alternatively, the scan may detect an indeterminate lesion and further evaluation may be performed by obtaining a physical sample of the lesion.

Imaging

Ultrasound, CT scan, and MRI may be used to evaluate the liver for HCC. On CT and MRI, HCC can have three distinct patterns of growth:

- A single large tumor

- Multiple tumors

- Poorly defined tumor with an infiltrative growth pattern

A systematic review of CT diagnosis found that the sensitivity was 68 percent (95% CI 55-80%) and specificity was 93 percent (95% CI 89-96%) compared with pathologic examination of an explanted or resected liver as the reference standard. With triple-phase helical CT, the sensitivity 90% or higher, but this data has not been confirmed with autopsy studies.[27]

However, MRI has the advantage of delivering high-resolution images of the liver without ionizing radiation. HCC appears as a high-intensity pattern on T2 weighted images and a low-intensity pattern on T1 weighted images. The advantage of MRI is that is has improved sensitivity and specificity when compared to US and CT in cirrhotic patients with whom it can be difficult to differentiate HCC from regenerative nodules. A systematic review found that the sensitivity was 81 percent (95% CI 70-91%) and specificity was 85 percent (95% CI 77-93%) compared with pathologic examination of an explanted or resected liver as the reference standard.[27] The sensitivity is further increased if gadolinium contrast-enhanced and diffusion-weighted imaging are combined.

MRI is more sensitive and specific than CT.[29]

Liver Image Reporting and Data System (LI-RADS) is a classification system for the reporting of liver lesions detected on CT and MRI. Radiologists use this standardized system to report on suspicious lesions and to provide an estimated likelihood of malignancy. Categories range from LI-RADS (LR) 1 to 5, in order of concern for cancer.[30] A biopsy is not needed to confirm the diagnosis of HCC if certain imaging criteria are met.

Pathology

Macroscopically, liver cancer appears as a nodular or infiltrative tumor. The nodular type may be solitary (large mass) or multiple (when developed as a complication of cirrhosis). Tumor nodules are round to oval, gray or green (if the tumor produces bile), well circumscribed but not encapsulated. The diffuse type is poorly circumscribed and infiltrates the portal veins, or the hepatic veins (rarely).

Microscopically, there are four architectural and cytological types (patterns) of hepatocellular carcinoma: fibrolamellar, pseudoglandular (adenoid), pleomorphic (giant cell) and clear cell. In well-differentiated forms, tumor cells resemble hepatocytes, form trabeculae, cords, and nests, and may contain bile pigment in the cytoplasm. In poorly differentiated forms, malignant epithelial cells are discohesive, pleomorphic, anaplastic, giant. The tumor has a scant stroma and central necrosis because of the poor vascularization.[31]

Staging

The prognosis of HCC is affected by the staging of the tumor as well as the liver's function due to the effects of liver cirrhosis.[32]

There are a number of staging classifications for HCC available; however, due to the unique nature of the carcinoma in order to fully encompass all the features that affect the categorization of the HCC, a classification system should incorporate; tumor size and number, presence of vascular invasion and extrahepatic spread, liver function (levels of serum bilirubin and albumin, presence of ascites and portal hypertension) and general health status of the patient (defined by the ECOG classification and the presence of symptoms).[32]

Out of all the staging classification systems available the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) staging classification encompasses all of the above characteristics. This staging classification can be used in order to select people for treatment.[33]

Important features that guide treatment include the following:

- size

- spread (stage)

- involvement of liver vessels

- presence of a tumor capsule

- presence of extrahepatic metastases

- presence of daughter nodules

- vascularity of the tumor

MRI is the best imaging method to detect the presence of a tumor capsule.

The most common sites of metastasis are the lung, abdominal lymph nodes, and bone.[34]

Prevention

Since hepatitis B or C is one of the main causes of hepatocellular carcinoma, prevention of this infection is key to then prevent hepatocellular carcinoma. Thus, childhood vaccination against hepatitis B may reduce the risk of liver cancer in the future.[35]

In the case of patients with cirrhosis, alcohol consumption is to be avoided. Also, screening for hemochromatosis may be beneficial for some patients.[36]

It is unclear if screening those with chronic liver disease for hepatocellular carcinoma improves outcomes.[37]

Treatment

Treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma varies by the stage of disease, a person's likelihood to tolerate surgery, and availability of liver transplant:

- Curative intention: for limited disease, when the cancer is limited to one or more areas of within the liver, surgically removing the malignant cells may be curative. This may be accomplished by resection the affected portion of the liver (partial hepatectomy) or in some cases by orthotopic liver transplantation of the entire organ.

- "Bridging" intention: for limited disease which qualifies for potential liver transplantation, the person may undergo targeted treatment of some or all of the known tumor while waiting for a donor organ to become available.[38]

- "Downstaging" intention: for moderately advanced disease which has not spread beyond the liver, but is too advanced to qualify for curative treatment. The person may be treated by targeted therapies in order to reduce the size or number of active tumors, with the goal of once again qualifying for liver transplant after this treatment.[38]

- Palliative intention: for more advanced disease, including spread of cancer beyond the liver or in persons who may not tolerate surgery, treatment intended to decrease symptoms of disease and maximize duration of survival.

Loco-regional therapy (also referred to as liver-directed therapy) refers to any one of several minimally-invasive treatment techniques to focally target HCC within the liver. These procedures are alternatives to surgery, and may be considered in combination with other strategies, such as a later liver transplantation.[39] Generally, these treatment procedures are performed by interventional radiologists or surgeons, in coordination with a medical oncologist. Loco-regional therapy may refer to either percutaneous therapies, such as microwave or cryoablation, or arterial catheter-based therapies, such as chemoembolization and radioembolization.

Surgical resection

Surgical resection to remove the tumor while preserving enough remaining healthy liver to maintain normal physiologic function. Surgical removal results in favorable prognosis, but only 10-15% of patients are suitable for surgical resection. This is often because of extensive disease or poor underlying liver function. For example, resection in cirrhotic patients is associated with higher morbidity and mortality. Preoperative evaluation for resection must include imaging of the liver in order to estimate the amount of residual liver remaining after surgery; in order to preserve normal function, the residual liver volume should be more than 25% of the total size in a non-cirrhotic liver, and more than 40% of the total size for a cirrhotic liver.[40] The overall recurrence rate after resection is 50-60%. The Singapore Liver Cancer Recurrence (SLICER) score can be used to estimate risk of recurrence after surgery.[41]

Liver transplantation

Liver transplantation to replace the diseased liver with a cadaveric liver or a living donor graft has historically low survival rates (20%-36%). During 1996–2001 the rate had improved to 61.1%, likely related to adoption of the Milan criteria at US transplantation centers. Expanded Shanghai criteria in China resulted in overall survival and disease-free survival rates similar to the Milan criteria.[42] Studies from the late 2000 obtained higher survival rates ranging from 67% to 91%.[43] If the liver tumor has metastasized, the immuno-suppressant post-transplant drugs decrease the chance of survival. Considering this objective risk in conjunction with the potentially high rate of survival, some recent studies conclude that: "LTx can be a curative approach for patients with advanced HCC without extrahepatic metastasis".[44] For those reasons, and others, it is considered nowadays that patient selection is a major key for success.[45]

Ablation

- Radiofrequency ablation (RFA) uses high-frequency radio waves to destroy tumor by local heating. The electrodes are inserted into the liver tumor under ultrasound image guidance using percutaneous, laparoscopic or open surgical approach. It is suitable for small tumors (<5 cm). RFA has the best outcomes in patients with a solitary tumor less than 4 mm.[46] Since it is a local treatment and has minimal effect on normal healthy tissue, it can be repeated multiple times. Survival is better for those with smaller tumors. In one study, In one series of 302 patients, the three-year survival rates for lesions >5 cm, 2.1 to 5 cm, and ≤2 cm were 59, 74, and 91 percent, respectively.[47] A large randomized trial comparing surgical resection and RFA for small HCC showed similar 4 year survival and less morbidities for patients treated with RFA.[48]

- Cryoablation: Cryoablation is a technique used to destroy tissue using cold temperature. The tumor is not removed and the destroyed cancer is left to be reabsorbed by the body. Initial results in properly selected patients with unresectable liver tumors are equivalent to those of resection. Cryosurgery involves the placement of a stainless steel probe into the center of the tumor. Liquid nitrogen is circulated through the end of this device. The tumor and a half inch margin of normal liver are frozen to -190 °C for 15 minutes, which is lethal to all tissues. The area is thawed for 10 minutes and then re-frozen to -190 °C for another 15 minutes. After the tumor has thawed, the probe is removed, bleeding is controlled, and the procedure is complete. The patient will spend the first post-operative night in the intensive care unit and typically is discharged in 3 – 5 days. Proper selection of patients and attention to detail in performing the cryosurgical procedure are mandatory in order to achieve good results and outcomes. Frequently, cryosurgery is used in conjunction with liver resection as some of the tumors are removed while others are treated with cryosurgery.

- Percutaneous ethanol injection (PEI) well tolerated, high RR in small (<3 cm) solitary tumors; as of 2005, no randomized trial comparing resection to percutaneous treatments; recurrence rates similar to those for postresection. However a comparative study found that local therapy can achieve a 5-year survival rate of around 60% for patients with small HCC.[49]

Arterial catheter based treatment

- Transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE) is usually performed for unresectable tumors or as a temporary treatment while waiting for liver transplant. TACE is done by injecting an antineoplastic drug (e.g. cisplatin) mixed with a radio-opaque contrast (e.g. Lipiodol) and an embolic agent (e.g. Gelfoam) into the right or left hepatic artery via the groin artery. The goal of the procedure it to restrict the tumor’s vascular supply while supplying a targeted chemotherapeutic agent. TACE has been shown to increase survival and to downstage HCC in patients who exceed the Milan criteria for liver transplant. Patients who undergo the procedure may are followed with CT scans and may need additional TACE procedures if the tumor persists.[50] As of 2005, multiple trials show objective tumor responses and slowed tumor progression but questionable survival benefit compared to supportive care; greatest benefit seen in people with preserved liver function, absence of vascular invasion, and smallest tumors. TACE is not suitable for big tumors (>8 cm), the presence of portal vein thrombus, tumors with a portal-systemic shunt, and patients with poor liver function.

- Selective internal radiation therapy (SIRT) can be used to destroy the tumor from within (thus minimizing exposure to healthy tissue). Similar to TACE, this is a procedure in which an interventional radiologist selectively injects the artery or arteries supplying the tumor with a chemotherapeutic agent. The agent is typically Yttrium-90 (Y-90) incorporated into embolic microspheres that lodge in the tumor vasculature causing ischemia and delivering their radiation dose directly to the lesion. This technique allows for a higher, local dose of radiation to be delivered directly to the tumor while sparing normal healthy tissue. While not curative, patients have increased survival. No studies have been done to compare whether SIRT is superior to TACE in terms of survival outcomes, although retrospective studies suggest similar efficacy.[51] There are currently two products available, SIR-Spheres and TheraSphere. The latter is an FDA approved treatment for primary liver cancer (HCC) which has been shown in clinical trials to increase the survival rate of low-risk patients. SIR-Spheres are FDA approved for the treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer but outside the US SIR-Spheres are approved for the treatment of any non-resectable liver cancer including primary liver cancer.

Systemic

Systemic therapy is considered in people with advanced HCC which has spread beyond the liver to other areas of the body. Currently, the multikinase inhibitor sorafenib is the only chemotherapy shown to be effective against HCC.[52]

Other

- Portal Vein Embolization (PVE): Using a percutaneous transhepatic approach, an interventional radiologist embolizes the portal vein supplying the side of the liver with the tumor. Compensatory hypertrophy of the surviving lobe can qualify the patient for resection. This procedure can also serve as a bridge to transplant.[53]

- High intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) (not to be confused with normal diagnostic ultrasound) is a technique uses powerful ultrasound to treat the tumor.

- A systematic review assessed 12 articles involving a total of 318 patients with hepatocellular carcinoma treated with Yttrium-90 radioembolization.[54] Excluding a study of only one patient, post-treatment CT evaluation of the tumor showed a response ranging from 29 to 100% of patients evaluated, with all but two studies showing a response of 71% or greater.

Prognosis

The usual outcome is poor, because only 10–20% of hepatocellular carcinomas can be removed completely using surgery. If the cancer cannot be completely removed, the disease is usually deadly within 3 to 6 months.[55] This is partially due to late presentation with tumors, but also the lack of medical expertise and facilities in the regions with high HCC prevalence. However, survival can vary, and occasionally people will survive much longer than 6 months. The prognosis for metastatic or unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma has recently improved due to the approval of sorafenib (Nexavar®) for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma.

Epidemiology

HCC is one of the most common tumors worldwide. The epidemiology of HCC exhibits two main patterns, one in North America and Western Europe and another in non-Western countries, such as those in sub-Saharan Africa, central and Southeast Asia, and the Amazon basin. Males are affected more than females usually and it is most common between the age of 30 to 50,[57] Hepatocellular carcinoma causes 662,000 deaths worldwide per year[58] about half of them in China.

Africa and Asia

In some parts of the world, such as sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia, HCC is the most common cancer, generally affecting men more than women, and with an age of onset between late teens and 30s. This variability is in part due to the different patterns of hepatitis B and hepatitis C transmission in different populations - infection at or around birth predispose to earlier cancers than if people are infected later. The time between hepatitis B infection and development into HCC can be years, even decades, but from diagnosis of HCC to death the average survival period is only 5.9 months according to one Chinese study during the 1970-80s, or 3 months (median survival time) in Sub-Saharan Africa according to Manson's textbook of tropical diseases. HCC is one of the deadliest cancers in China where chronic hepatitis B is found in 90% of cases. In Japan, chronic hepatitis C is associated with 90% of HCC cases. Food infected with Aspergillus flavus (especially peanuts and corns stored during prolonged wet seasons) which produces aflatoxin poses another risk factor for HCC.

In the Eastern Asian hemisphere, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most common type of cancer. The common risk factor for HCC in Asia is the high diagnosis of Hepatitis B. However, in Japan the common risk factor is hepatitis C. Another factor is that causes HCC is a mycotoxin called aflatoxin. This mycotoxin is found among many areas in Asia with Southern China being the Asian country with the highest amount of aflatoxin. Thus, China is the country with the highest diagnosis of HCC in Eastern Asia.[59][60]

North America and Western Europe

The most common malignant tumors in the liver represent metastases (spread) from tumors which originate elsewhere in the body.[57] Among cancer that originate from liver tissue, HCC is the most common primary liver cancer. In the United States, the US surveillance, epidemiology, and end results (SEER) database program, shows that HCC accounts for 65% of all cases of liver cancers.[61] As there are screening programs in place for high risk persons with chronic liver disease, HCC is often discovered much earlier in Western countries than in developing regions such as Sub-Saharan Africa.

Acute and chronic hepatic porphyrias (acute intermittent porphyria, porphyria cutanea tarda, hereditary coproporphyria, variegate porphyria) and tyrosinemia type I are risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma. The diagnosis of an acute hepatic porphyria (AIP, HCP, VP) should be sought in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma without typical risk factors of hepatitis B or C, alcoholic liver cirrhosis or hemochromatosis. Both active and latent genetic carriers of acute hepatic porphyrias are at risk for this cancer, although latent genetic carriers have developed the cancer at a later age than those with classic symptoms. Patients with acute hepatic porphyrias should be monitored for hepatocellular carcinoma.

The incidence of HCC is relatively lower in the Western hemisphere than in Eastern Asia. However, despite the statistics being low, there is an increase of HCC in the West. The diagnosis of HCC has increased since the 1980s and it is continuing to increase, making it one of the rising cause of death due to cancer. The common risk factor for HCC is hepatitis C, along with other health issues.[59][60]

Research

Pre-clinical

Current research includes the search for the genes that are disregulated in HCC, anti-heparanase antibodies,[62] protein markers,[63] non-coding RNAs (such as TUC338)[64] and other predictive biomarkers.[65][66] As similar research is yielding results in various other malignant diseases, it is hoped that identifying the aberrant genes and the resultant proteins could lead to the identification of pharmacological interventions for HCC.[67]

Clinical

JX-594, an oncolytic virus, has orphan drug designation for this condition and is undergoing clinical trials.[68]

Hepcortespenlisimut-L, an oral cancer vaccine also has US FDA orphan drug designation for hepatocellular carcinoma.[69]

A randomized trial of people with advanced HCC showed no benefit for the combination of everolimus and pasireotide.[70]

Abbreviations

HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; TACE, transarterial embolization/chemoembolization; PFS, progression-free survival; PS, performance status; HBV, hepatitis B virus; PEI, percutaneous ethanol injection; RFA, radiofrequency ablation; RR, response rate; MS, median survival.

See also

References

- ↑ Forner A, Llovet JM, Bruix J (2012). "Hepatocellular carcinoma". The Lancet. 379 (9822): 1245–1255. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61347-0.

- 1 2 Kumar V, Fausto N, Abbas A, eds. (2015). Robbins & Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease (9th ed.). Saunders. pp. 870–873. ISBN 978-1455726134.

- ↑ "Liver cancer overview". Mayo Clinic.

- 1 2 Heidelbaugh, Joel J.; Bruderly, Michael (2006-09-01). "Cirrhosis and chronic liver failure: part I. Diagnosis and evaluation". American Family Physician. 74 (5): 756–762. ISSN 0002-838X. PMID 16970019.

- ↑ Alter MJ (2007). "Epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 13 (17): 2436–41. PMID 17552026. doi:10.3748/wjg.v13.i17.2436.

- ↑ White DL, Kanwal F, El-Serag HB (2012). "Association between nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and risk for hepatocellular cancer, based on systematic review". Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 10 (12): 1342–59. PMC 3501546

. PMID 23041539. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2012.10.001.

. PMID 23041539. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2012.10.001. - 1 2 3 El–Serag HB; Hampel H; Javadi F (2006). "the association between diabetes and hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review of epidemiological evidence". Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 4 (3): 369–380. PMID 16527702. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2005.12.007.

Diabetes is associated with an increased risk for HCC. However, more research is required to examine issues related to the duration and treatment of diabetes, and confounding by diet and obesity

- ↑ Wang XW, Hussain SP, Huo TI, Wu CG, Forgues M, Hofseth LJ, Brechot C, Harris CC (2002). "Molecular pathogenesis of human hepatocellular carcinoma". Toxicology. 181–182: 43–47. PMID 12505283. doi:10.1016/S0300-483X(02)00253-6.

Recent studies in our laboratory have identified several potential factors that may contribute to the pathogenesis of HCC...For example, oxyradical overload diseases such as Wilson disease and hemochromatosis result in the generation of oxygen/nitrogen species that can cause mutations in the p53 tumour suppressor gene

- ↑ Cheng W, Govindarajan S, Redeker A (1992). "Hepatocellular carcinoma in a case of Wilson's disease". Liver International. 12 (1): 42–45. PMID 1314321. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0676.1992.tb00553.x.

The patient described here was the oldest and only the third female patient with hepatocellular carcinoma complicating Wilson's disease to be reported in the literature

- ↑ Wilkinson ML, Portmann B, Williams R (1983). "Wilson's disease and hepatocellular carcinoma: possible protective role of copper". Gut. 24 (8): 767–771. PMC 1420230

. PMID 6307837. doi:10.1136/gut.24.8.767.

. PMID 6307837. doi:10.1136/gut.24.8.767. As copper has been shown to protect against chemically induced hepatocellular carcinoma in rats, this may be the reason for the extreme rarity of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with Wilson's disease and possibly in other liver diseases with hepatic copper overload

- ↑ Huang YC, Tsan YT, Chan WC, Wang JD, Chu WM, Fu YC, Tong KM, Lin CH, Chang ST, Hwang WL (2015). "Incidence and survival of cancers among 1,054 hemophilia patients: A nationwide and 14-year cohort study". American Journal of Hematology. 90 (4): E55–E59. doi:10.1002/ajh.23947.

- ↑ Shetty, Shrimati; Sharma, Nitika; Ghosh, Kanjaksha (2016-03-01). "Epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in hemophilia". Critical Reviews in Oncology / Hematology. 99: 129–133. ISSN 1040-8428. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2015.12.009.

- ↑ Tanaka M, Katayama F, Kato H, Tanaka H, Wang J, Qiao YL, Inoue M (2011). "Hepatitis B and C virus infection and hepatocellular carcinoma in China: A review of epidemiology and control measures". Journal of Epidemiology. 21 (6): 401–416. PMC 3899457

. PMID 22041528. doi:10.2188/jea.JE20100190.

. PMID 22041528. doi:10.2188/jea.JE20100190. - ↑ "Pathophysiology". Retrieved May 12, 2010.

- 1 2 3 Hassan MM, Curley SA, Li D, Kaseb A, Davila M, Abdalla EK, Javle M, Moghazy DM, Lozano RD, Abbruzzese JL, Vauthey JN (2010). "Association of diabetes duration and diabetes treatment with the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma". Cancer. 116 (8): 1938–1946. PMID 20166205. doi:10.1002/cncr.24982.

Diabetes appears to increase the risk of HCC, and such risk is correlated with a long duration of diabetes. Relying on dietary control and treatment with sulfonylureas or insulin were found to confer the highest magnitude of HCC risk, whereas treatment with biguanides or thiazolidinediones was associated with a 70% HCC risk reduction among diabetics.

- 1 2 Donadon, Valter (2009). "Antidiabetic therapy and increased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic liver disease". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 15 (20): 2506–11. PMC 2686909

. PMID 19469001. doi:10.3748/wjg.15.2506.

. PMID 19469001. doi:10.3748/wjg.15.2506. Our study confirms that type 2 diabetes mellitus is an independent risk factor for HCC and pre-exists in the majority of HCC patients. Moreover, in male patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, our data shows a direct association of HCC with insulin and sulphanylureas treatment and an inverse relationship with metformin therapy.

- ↑ Donadon V, Balbi M, Ghersetti M; et al. (2009). "Antidiabetic therapy and increased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic liver disease". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 15 (20): 2506–11. PMC 2686909

. PMID 19469001. doi:10.3748/wjg.15.2506.

. PMID 19469001. doi:10.3748/wjg.15.2506. - ↑ Siegel A, Zhu AX (2009). "Metabolic Syndrome and hepatocellular carcinoma". Cancer. 115 (24): 5651–5661. PMC 3397779

. PMID 19834957. doi:10.1002/cncr.24687.

. PMID 19834957. doi:10.1002/cncr.24687. The majority of 'cryptogenic' HCC in the United States is attributed to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), a hepatic manifestation of the metabolic syndrome... It is predicted that metabolic syndrome will lead to large increases in the incidence of HCC over the next decades. A better understanding of the relation between these 2 diseases ultimately should lead to improved screening and treatment options for patients with HCC.

- ↑ Stickely F, Hellerbrand C (2010). "Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease as a risk factor for hepatocellular carcinoma: mechanisms and implications". Gut. 59 (10): 1303–1307. PMID 20650925. doi:10.1136/gut.2009.199661.

Based on the known association of NAFLD with IR and MS, approximately two-thirds of the patients were obese and/or diabetic, 4 and a remarkable 25% of these patients had no cirrhosis... Therefore, it is particularly worrying that the most persuasive evidence for an association between NAFLD and HCC derives from studies on the risk of HCC in patients with metabolic syndrome

- ↑ "Hepatocellular Carcinoma and Diseases". Retrieved May 12, 2010.

- ↑ Höpfner M, Huether A, Sutter AP, Baradari V, Schuppan D, Scherübl H (2006). "Blockade of IGF-1 receptor tyrosine kinase has antineoplastic effects in hepatocellular carcinoma cells". Biochemical Pharmacology. 71 (10): 1435–1448. PMID 16530734. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2006.02.006.

Inhibition of IGF-1R tyrosine kinase (IGF-1R-TK) by NVP-AEW541 induces growth inhibition, apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in human HCC cell lines without accompanying cytotoxicity. Thus, IGF-1R-TK inhibition may be a promising novel treatment approach in HCC.

- ↑ Huynh H, Chow PK, Ooi LL, Soo KC (2002). "A possible role for insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-3 autocrine/paracrine loops in controlling hepatocellular carcinoma cell proliferation". Cell Growth and Differentiation. 13 (3): 115–122. PMID 11959812.

Our data indicate that loss of autocrine/paracrine IGFBP-3 loops may lead to HCC tumor growth and suggest that modulating production of the IGFs, IGFBP-3, and IGF-IR may represent a novel approach in the treatment of HCC.

- ↑ Martin NM, Abu Dayyeh BK, Chung RT (2008). "Anabolic steroid abuse causing recurrent hepatic adenomas and hemorrhage". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 14 (28): 4573–4575. PMC 2731289

. PMID 18680242. doi:10.3748/wjg.14.4573.

. PMID 18680242. doi:10.3748/wjg.14.4573. This is the first reported case of hepatic adenoma re-growth with recidivistic steroid abuse, complicated by life-threatening hemorrhage.

- ↑ Gorayski P, Thompson CH, Subhash HS, Thomas AC (2007). "Hepatocellular carcinoma associated with recreational anabolic steroid use". British Journal of Sports Medicine. 42 (1): 74–75. PMID 18178686. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2007.03932.

Malignant transformation to HCC from a pre-existing hepatic adenoma confirmed by immunohistochemical study has previously not been reported in athletes taking anabolic steroids. Further studies using screening programmes to identify high-risk individuals are recommended.

- ↑ Chien-Jen Chen; Hwai-I. Yang; Jun Su; Chin-Lan Jen; San-Lin You; Sheng-Nan Lu; Guan-Tarn Huang; Uchenna H. Iloeje (2006). "Risk of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Across a Biological Gradient of Serum Hepatitis B Virus DNA Level". JAMA. 295 (1): 65–73. PMID 16391218. doi:10.1001/jama.295.1.65.

- ↑ "Clinical features and diagnosis of primary hepatocellular carcinoma". UptoDate. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

- 1 2 3 Colli, A; Fraquelli, M; Casazza, G; Massironi, S; Colucci, A; Conte, D; Duca, P (March 2006). "Accuracy of ultrasonography, spiral CT, magnetic resonance, and alpha-fetoprotein in diagnosing hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review". The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 101 (3): 513–23. PMID 16542288. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00467.x.

- ↑ Ertle, JM; Heider, D; Wichert, M; Keller, B; Kueper, R; Hilgard, P; Gerken, G; Schlaak, JF (2013). "A combination of α-fetoprotein and des-γ-carboxy prothrombin is superior in detection of hepatocellular carcinoma". Digestion. 87 (2): 121–31. PMID 23406785. doi:10.1159/000346080.

- ↑ El-Serag HB, Marrero JA, Rudolph L, Reddy KR (May 2008). "Diagnosis and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma". Gastroenterology. 134 (6): 1752–63. PMID 18471552. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2008.02.090.

- ↑ http://www.acr.org/Quality-Safety/Resources/LIRADS

- ↑ Hepatocellular carcinoma (Photo) ATLAS OF PATHOLOGY

- 1 2 Duseja, Ajay (2014-08-01). "Staging of Hepatocellular Carcinoma". Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hepatology. 4: S74–S79. PMC 4284240

. PMID 25755615. doi:10.1016/j.jceh.2014.03.045.

. PMID 25755615. doi:10.1016/j.jceh.2014.03.045. - ↑ Llovet JM, Brú C, Bruix J (1999). "Prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: the BCLC staging classification". Seminars in Liver Disease. 19: 329–38. PMID 10518312. doi:10.1055/s-2007-1007122.

- ↑ Katyal, Sanjeev; Oliver, James H.; Peterson, Mark S.; Ferris, James V.; Carr, Brian S.; Baron, Richard L. (2000). "Extrahepatic Metastases of Hepatocellular Carcinoma". Radiology. 216 (3): 698–703. doi:10.1148/radiology.216.3.r00se24698.

- ↑ "Hepatitis B: Prevention and treatment". Archived from the original on 24 July 2013. Retrieved 28 August 2013. "WHO aims at controlling HBV worldwide to decrease the incidence of HBV-related chronic liver disease, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma. by integrating HB vaccination into routine infant (and possibly adolescent) immunization programs."

- ↑ "Prevention". Retrieved May 12, 2010.

- ↑ Kansagara, Devan; Papak, Joel; Pasha, Amirala S.; O'Neil, Maya; Freeman, Michele; Relevo, Rose; Quiñones, Ana; Motu'apuaka, Makalapua; et al. (17 June 2014). "Screening for Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Chronic Liver Disease". Annals of Internal Medicine. 161: 261. doi:10.7326/M14-0558.

- 1 2 Pompili, Maurizio. "Bridging and downstaging treatments for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients on the waiting list for liver transplantation". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 19 (43): 7515. PMC 3837250

. PMID 24282343. doi:10.3748/wjg.v19.i43.7515.

. PMID 24282343. doi:10.3748/wjg.v19.i43.7515. - ↑ Gbolahan, Olumide B.; Schacht, Michael A.; Beckley, Eric W.; LaRoche, Thomas P.; O'Neil, Bert H.; Pyko, Maximilian (April 2017). "Locoregional and systemic therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma". Journal of Gastrointestinal Oncology. 8 (2): 215–228. ISSN 2078-6891. PMC 5401862

. PMID 28480062. doi:10.21037/jgo.2017.03.13.

. PMID 28480062. doi:10.21037/jgo.2017.03.13. - ↑ Ma, Ka Wing; Cheung, Tan To (December 2016). "Surgical resection of localized hepatocellular carcinoma: patient selection and special consideration". Journal of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Volume 4: 3. doi:10.2147/JHC.S96085.

- ↑ "The Singapore Liver Cancer Recurrence (SLICER) Score for Relapse Prediction in Patients with Surgically Resected Hepatocellular Carcinoma". PLOS ONE. 10: e0118658. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0118658

.

. - ↑ Fan, Jia; Yang, Guang-Shun; Fu, Zhi-Ren; Peng, Zhi-Hai; Xia, Qiang; Peng, Chen-Hong; Qian, Jian-Ming; Zhou, Jian; Xu, Yang; et al. (2009). "Liver transplantation outcomes in 1,078 hepatocellular carcinoma patients: a multi-center experience in Shanghai, China". Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology. 135 (10): 1403–1412. PMID 19381688. doi:10.1007/s00432-009-0584-6.

- ↑ Vitale, Alessandro; Gringeri, Enrico; Valmasoni, Michele; D'Amico, Francesco; Carraro, Amedeo; Pauletto, Alberto; D'Amico, Francesco Jr.; Polacco, Marina; D'Amico, Davide Francesco; Cillo, Umberto (2007). "Longterm results of liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: an update of the University of Padova experience". Transplantation Proceedings. 39 (6): 1892–1894. PMID 17692645. doi:10.1016/j.transproceed.2007.05.031.

- ↑ Obed, Aiman; Tsui, Tung-Yu; Schnitzbauer, Andreas A.; Obed, Manal; Schlitt, Hans J.; Becker, Heinz; Lorf, Thomas (2009). "Liver Transplantation for Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Need for a New Patient Selection Strategy: Reply". Langenbeck's Archives of Surgery. 393 (2): 141–147. PMC 1356504

. PMID 18043937. doi:10.1007/s00423-007-0250-x

. PMID 18043937. doi:10.1007/s00423-007-0250-x  .

. - ↑ Cillo, Umberto; Vitale, Alessandro; Bassanello, Marco; Boccagni, Patrizia; Brolese, Alberto; Zanus, Giacomo; Burra, Patrizia; Fagiuoli, Stefano; Farinati, Fabio; Rugge, Massimo; d'Amico, Davide Francesco (February 2004). "Liver transplantation for the treatment of moderately or well-differentiated hepatocellular carcinoma". Annals of Surgery. 239 (2): 150–9. PMC 1356206

. PMID 14745321. doi:10.1097/01.sla.0000109146.72827.76.

. PMID 14745321. doi:10.1097/01.sla.0000109146.72827.76. - ↑ Tanabe, KK; Curley, SA; Dodd, GD; Siperstein, AE; Goldberg, SN (February 1, 2004). "Radiofrequency ablation: the experts weigh in". Cancer. 100 (3): 641–50. PMID 14745883. doi:10.1002/cncr.11919.

- ↑ Tateishi, R; Shiina, S; Teratani, T; Obi, S; Sato, S; Koike, Y; Fujishima, T; Yoshida, H; Kawabe, T; Omata, M (15 March 2005). "Percutaneous radiofrequency ablation for hepatocellular carcinoma. An analysis of 1000 cases". Cancer. 103 (6): 1201–9. PMID 15690326. doi:10.1002/cncr.20892.

- ↑ Chen, Min-Shan; Li, Jin-Qing; Zheng, Yun; Guo, Rong-Ping; Liang, Hui-Hong; Zhang, Ya-Qi; Lin, Xiao-Jun; Lau, Wan Y (2006). "A Prospective Randomized Trial Comparing Percutaneous Local Ablative Therapy and Partial Hepatectomy for Small Hepatocellular Carcinoma". Annals of Surgery. 243 (3): 321–8. PMC 1448947

. PMID 16495695. doi:10.1097/01.sla.0000201480.65519.b8.

. PMID 16495695. doi:10.1097/01.sla.0000201480.65519.b8. - ↑ Yamamoto, Junji; Okada, Shuichi; Shimada, Kazuaki; Okusaka, Takushi; Yamasaki, Susumu; Ueno, Hideki; Kosuge, Tomoo (2001). "Treatment strategy for small hepatocellular carcinoma: Comparison of long-term results after percutaneous ethanol injection therapy and surgical resection". Hepatology. 34 (4): 707–713. PMID 11584366. doi:10.1053/jhep.2001.27950.

- ↑ "Interventional Radiology Treatments for Liver Cancer". Society of Interventional Radiology. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

- ↑ Kooby, DA; Egnatashvili, V; Srinivasan, S; Chamsuddin, A; Delman, KA; Kauh, J; Staley CA, 3rd; Kim, HS (February 2010). "Comparison of yttrium-90 radioembolization and transcatheter arterial chemoembolization for the treatment of unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma". Journal of Vascular and Interventional Radiology. 21 (2): 224–30. PMID 20022765. doi:10.1016/j.jvir.2009.10.013.

- ↑ Llovet, Josep M.; Ricci, Sergio; Mazzaferro, Vincenzo; Hilgard, Philip; Gane, Edward; Blanc, Jean-Frédéric; de Oliveira, Andre Cosme; Santoro, Armando; Raoul, Jean-Luc (2008-07-24). "Sorafenib in Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma". New England Journal of Medicine. 359 (4): 378–390. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 18650514. doi:10.1056/nejmoa0708857.

- ↑ Madoff, DC; Hicks, ME; Vauthey, JN; Charnsangavej, C; Morello FA, Jr; Ahrar, K; Wallace, MJ; Gupta, S (September–October 2002). "Transhepatic portal vein embolization: anatomy, indications, and technical considerations". Radiographics. 22 (5): 1063–76. PMID 12235336. doi:10.1148/radiographics.22.5.g02se161063.

- ↑ Vente MA, Wondergem M, van der Tweel I, et al. (April 2009). "Yttrium-90 microsphere radioembolization for the treatment of liver malignancies: a structured meta-analysis". European Radiology. 19 (4): 951–9. PMID 18989675. doi:10.1007/s00330-008-1211-7.

- ↑ Hepatocellular carcinoma MedlinePlus, Medical Encyclopedia

- ↑ "WHO Disease and injury country estimates". World Health Organization. 2009. Retrieved November 11, 2009.

- 1 2 Kumar V, Fausto N, Abbas A (editors) (2015). Robbins & Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease (9th ed.). Elsevier/Saunders. pp. 821–881. ISBN 9780323266161.

- ↑ "Cancer". World Health Organization. February 2006. Retrieved 2007-05-24.

- 1 2 Choo, Su Pin; Tan, Wan Ling; Goh, Brian K. P.; Tai, Wai Meng; Zhu, Andrew X. (15 November 2016). "Comparison of hepatocellular carcinoma in Eastern versus Western populations". Cancer. 122 (22): 3430–3446. doi:10.1002/cncr.30237.

- 1 2 Goh, George Boon-Bee; Chang, Pik-Eu; Tan, Chee-Kiat (December 2015). "Changing epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma in Asia". Best Practice & Research Clinical Gastroenterology. 29 (6): 919–928. doi:10.1016/j.bpg.2015.09.007.

- ↑ Rowe, JulieH; Ghouri, YezazAhmed; Mian, Idrees (2017-01-01). "Review of hepatocellular carcinoma: Epidemiology, etiology, and carcinogenesis". Journal of Carcinogenesis. 16 (1). doi:10.4103/jcar.jcar_9_16.

- ↑ Yang, Jian-min; Wang, Hui-ju; Du, Ling; Han, Xiao-mei; Ye, Zai-yuan; Fang, Yong; Tao, Hou-quan; Zhao, Zhong-sheng; Zhou, Yong-lie (2009-01-25). "Screening and identification of novel B cell epitopes in human heparanase and their anti-invasion property for hepatocellular carcinoma". Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy. 58 (9): 1387–1396. doi:10.1007/s00262-008-0651-x.

- ↑ Huntington Medical Research Institute News, May 2005

- ↑ Braconi, C; Valeri, N, Kogure, T, Gasparini, P, Huang, N, Nuovo, GJ, Terracciano, L, Croce, CM, Patel, T (2011-01-11). "Expression and functional role of a transcribed noncoding RNA with an ultraconserved element in hepatocellular carcinoma". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 108 (2): 786–91. PMC 3021052

. PMID 21187392. doi:10.1073/pnas.1011098108.

. PMID 21187392. doi:10.1073/pnas.1011098108. - ↑ Journal of Clinical Oncology, Special Issue on Molecular Oncology: Receptor-Based Therapy, April 2005

- ↑ Lau W, Leung T, Ho S, Chan M, Machin D, Lau J, Chan A, Yeo W, Mok T, Yu S, Leung N, Johnson P (1999). "Adjuvant intra-arterial iodine-131-labelled lipiodol for resectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a prospective randomised trial". The Lancet. 353 (9155): 797–801. PMID 10459961. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(98)06475-7.

- ↑ Thomas M, Zhu A (2005). "Hepatocellular carcinoma: the need for progress". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 23 (13): 2892–9. PMID 15860847. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.03.196.

- ↑ ennerex Granted FDA Orphan Drug Designation for Pexa-Vec in Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC) Archived March 25, 2014, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ FDA Orphan Drug database

- ↑ Sanoff, Hanna K.; Kim, Richard; Ivanova, Anastasia; Alistar, Angela; McRee, Autumn J.; O’Neil, Bert H. (2015). "Everolimus and pasireotide for advanced and metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma". Investigational New Drugs. 33 (2): 505–509. doi:10.1007/s10637-015-0209-7.

Further reading

- "Long-term results of liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: an update of the University of Padova experience". September 23, 2013. Retrieved 6 February 2014.

- Bruix, Jordi; Sherman, Morris; Practice Guidelines Committee (November 2005). "Management of hepatocellular carcinoma". Hepatology. 42 (5): 1208–1236. PMID 16250051. doi:10.1002/hep.20933.

- Liu, Chi-leung, M.D., "Hepatic Resection for Hepatocellular Carcinoma", The Hong Kong Medical Diary, Vol.10 No.12, December 2005 Medical Bulletin

External links

| Classification |

V · T · D |

|---|---|

| External resources |

- NCI Liver Cancer Homepage

- Blue Faery: The Adrienne Wilson Liver Cancer Association

- Liver cancer overview from Mayo Clinic