Hepatitis B virus

| Hepatitis B virus | |

|---|---|

| |

| TEM micrograph showing hepatitis B viruses | |

| Virus classification | |

| Group: | Group VII (dsDNA-RT) |

| Order: | Unassigned |

| Family: | Hepadnaviridae |

| Genus: | Orthohepadnavirus |

| Species: | Hepatitis B virus |

Hepatitis B virus, abbreviated HBV, is of the double stranded DNA type,[1] a species of the genus Orthohepadnavirus, which is likewise a part of the Hepadnaviridae family of viruses.[2] This virus causes the disease hepatitis B.[3]

Disease

In addition to causing hepatitis, infection with HBV can lead to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma.[4]

It has also been suggested that it may increase the risk of pancreatic cancer.[3]

Classification

The hepatitis B virus is classified as the type species of the Orthohepadnavirus, which contains three other species: the Ground squirrel hepatitis virus, Woodchuck hepatitis virus, and the Woolly monkey hepatitis B virus. The genus is classified as part of the Hepadnaviridae family, which contains two other genera, the Avihepadnavirus and a second which has yet to be assigned. This family of viruses have not been assigned to a viral order.[5] Viruses similar to hepatitis B have been found in all apes (orangutan, gibbons, gorillas and chimpanzees), in Old World monkeys,[6] and in a New World woolly monkeys suggesting an ancient origin for this virus in primates.

The virus is divided into four major serotypes (adr, adw, ayr, ayw) based on antigenic epitopes present on its envelope proteins. These serotypes are based on a common determinant (a) and two mutually exclusive determinant pairs (d/y and w/r). The viral strains have also been divided into ten genotypes (A–J) and forty subgenotypes according to overall nucleotide sequence variation of the genome.[7] The genotypes have a distinct geographical distribution and are used in tracing the evolution and transmission of the virus. Differences between genotypes affect the disease severity, course and likelihood of complications, and response to treatment and possibly vaccination.[8][9] The serotypes and genotypes do not necessarily correspond.

Genotype D has 10 subgenotypes.[10][7]

Unclassified species

A number of as yet unclassified Hepatitis B like species have been isolated from bats.[11]

Morphology

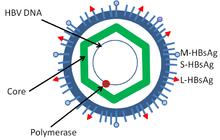

Structure

Hepatitis B virus is a member of the Hepadnavirus family.[12] The virus particle, called Dane particle[13] (virion), consists of an outer lipid envelope and an icosahedral nucleocapsid core composed of protein. The nucleocapsid encloses the viral DNA and a DNA polymerase that has reverse transcriptase activity similar to retroviruses.[14] The outer envelope contains embedded proteins which are involved in viral binding of, and entry into, susceptible cells. The virus is one of the smallest enveloped animal viruses with a virion diameter of 42 nm, but pleomorphic forms exist, including filamentous and spherical bodies lacking a core. These particles are not infectious and are composed of the lipid and protein that forms part of the surface of the virion, which is called the surface antigen (HBsAg), and is produced in excess during the life cycle of the virus.[15]

Components

It consists of:

- HBsAg

- HBcAg (HBeAg is a splice variant)

- Hepatitis B virus DNA polymerase

- HBx. The function of this protein is not yet well known,[16] but evidence suggests it plays a part in the activation of the viral transcription process.[17]

Hepatitis D virus requires HBV envelope particles to become virulent.[18]

Evolution

The early evolution of the Hepatitis B, like that of all viruses, is difficult to establish.

The divergence of orthohepadnavirus and avihepadnavirus occurred ~125,000 years ago (95% interval 78,297–313,500).[19] Both the Avihepadnavirus and Orthohepadna viruses began to diversify about 25,000 years ago.[19] The branching at this time lead to the emergence of the Orthohepadna genotypes A–H. Human strains have a most recent common ancestor dating back to 7,000 (95% interval: 5,287–9,270) to 10,000 (95% interval: 6,305–16,681) years ago.

The Avihepadnavirus lack a X protein but a vestigial X reading frame is present in the genome of duck hepadnavirus.[20] The X protein may have evolved from a DNA glycosylase.

The rate of nonsynonymous mutations in this virus has been estimated to be about 2×10−5 amino acid replacements per site per year.[21] The mean number of nucleotide substitutions/site/year is ~7.9×10−5.

A second estimate of the origin of this virus suggests a most recent common ancestor of the human strains evolved ~1500 years ago.[22] The most recent common ancestor of the avian strains was placed at 6000 years ago. The mutation rate was estimated to be ~10−6 substitutions/site/year.

Another analysis with a larger data set suggests that Hepatitis B infected humans 33,600 years ago (95% higher posterior density 22,000-47,100 years ago.[23] The estimated substitution rate was 2.2 × 10−6 substitutions/site/year. A significant increase in the population was noted within the last 5,000 years. Cross species infection to orangutans and gibbons occurred within the last 6,100 years.

Examination of sequences in the zebra finch have pushed the origin of this genus back at least to 40 million years ago and possibly to 80 million years ago.[24] Chimpanzee, gorilla, orangutan, and gibbons species cluster with human isolates. Non primate species included the woodchuck hepatitis virus, the ground squirrel hepatitis virus and arctic squirrel hepatitis virus. A number of bat infecting species have also been described. It has been proposed that a New World bat species may be the origin of the primate species.[25]

Genome

Size

The genome of HBV is made of circular DNA, but it is unusual because the DNA is not fully double-stranded. One end of the full length strand is linked to the viral DNA polymerase. The genome is 3020–3320 nucleotides long (for the full length strand) and 1700–2800 nucleotides long (for the short length strand).[26]

Encoding

The negative-sense, (non-coding) strand is complementary to the viral mRNA. The viral DNA is found in the nucleus soon after infection of the cell. The partially double-stranded DNA is rendered fully double-stranded by completion of the (+) sense strand by cellular DNA polymerases (viral DNA polymerase is used for a later stage) and removal of a protein molecule from the (-) sense strand and a short sequence of RNA from the (+) sense strand. Non-coding bases are removed from the ends of the (-)sense strand and the ends are rejoined.

The viral genes are transcribed by the cellular RNA polymerase II in the cell nucleus from a covalently closed circular DNA (cccDNA) template. Two enhancers designated enhancer I (EnhI) and enhancer II (EnhII) have been identified in the HBV genome. Both enhancers exhibit greater activity in cells of hepatic origin, and together they drive and regulate the expression of the complete viral transcripts.[27][28][29] There are four known genes encoded by the genome called C, P, S, and X. The core protein is coded for by gene C (HBcAg), and its start codon is preceded by an upstream in-frame AUG start codon from which the pre-core protein is produced. HBeAg is produced by proteolytic processing of the pre-core protein. The DNA polymerase is encoded by gene P. Gene S is the gene that codes for the surface antigen (HBsAg). The HBsAg gene is one long open reading frame but contains three in frame "start" (ATG) codons that divide the gene into three sections, pre-S1, pre-S2, and S. Because of the multiple start codons, polypeptides of three different sizes called large, middle, and small (pre-S1 + pre-S2 + S, pre-S2 + S, or S) are produced.[30] The function of the protein coded for by gene X is not fully understood,[31] but some evidence suggests that it may function as a transcriptional transactivator.

Several non-coding RNA elements have been identified in the HBV genome. These include: HBV PREalpha, HBV PREbeta and HBV RNA encapsidation signal epsilon.[32][33]

Genotypes

Genotypes differ by at least 8% of the sequence and have distinct geographical distributions and this has been associated with anthropological history. Within genotypes subtypes have been described: these differ by 4–8% of the genome.

There are eight known genotypes labeled A through H.[8]

A possible new "I" genotype has been described,[34] but acceptance of this notation is not universal.[35]

Two further genotypes have since been recognised.[36] The current (2014) listing now runs A though to J. Several subtypes are also recognised.

There are at least 24 subtypes.

Different genotypes may respond to treatment in different ways.[37][38]

- Individual genotypes

Type F which diverges from the other genomes by 14% is the most divergent type known. Type A is prevalent in Europe, Africa and South-east Asia, including the Philippines. Type B and C are predominant in Asia; type D is common in the Mediterranean area, the Middle East and India; type E is localized in sub-Saharan Africa; type F (or H) is restricted to Central and South America. Type G has been found in France and Germany. Genotypes A, D and F are predominant in Brazil and all genotypes occur in the United States with frequencies dependent on ethnicity.

The E and F strains appear to have originated in aboriginal populations of Africa and the New World, respectively.

Type A has two subtypes: Aa (A1) in Africa/Asia and the Philippines and Ae (A2) in Europe/United States.

Type B has two distinct geographical distributions: Bj/B1 ('j'—Japan) and Ba/B2 ('a'—Asia). Type Ba has been further subdivided into four clades (B2–B4).

Type C has two geographically subtypes: Cs (C1) in South-east Asia and Ce (C2) in East Asia. The C subtypes have been divided into five clades (C1–C5). A sixth clade (C6) has been described in the Philippines but only in one isolate to date.[39] Type C1 is associated with Vietnam, Myanmar and Thailand; type C2 with Japan, Korea and China; type C3 with New Caledonia and Polynesia; C4 with Australia; and C5 with the Philippines. A further subtype has been described in Papua, Indonesia.[40]

Type D has been divided into 7 subtypes (D1–D7).

Type F has been subdivided into 4 subtypes (F1–F4). F1 has been further divided into 1a and 1b. In Venezuela subtypes F1, F2, and F3 are found in East and West Amerindians. Among South Amerindians only F3 was found. Subtypes Ia, III, and IV exhibit a restricted geographic distribution (Central America, the North and the South of South America respectively) while clades Ib and II are found in all the Americas except in the Northern South America and North America respectively.

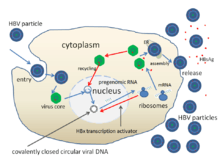

Life cycle

The life cycle of hepatitis B virus is complex. Hepatitis B is one of a few known non-retroviral viruses which use reverse transcription as a part of its replication process.

- Attachment

- The virus gains entry into the cell by binding to a receptor on the surface of the cell and enters it by clathrin-dependent endocytosis. The cell surface receptor has been identified as the Sodium/Bile acid cotransporting peptide SLC10A1 (also named NTCP).

- Penetration

- The virus membrane then fuses with the host cell's membrane releasing the DNA and core proteins into the cytoplasm.

- Uncoating

- Because the virus multiplies via RNA made by a host enzyme, the viral genomic DNA has to be transferred to the cell nucleus. It is thought the capsid is transported on the microtubules to the nuclear pore. The core proteins dissociate from the partially double stranded viral DNA which is then made fully double stranded (by host DNA polymerases) and transformed into covalently closed circular DNA (cccDNA) that serves as a template for transcription of four viral mRNAs.

- Replication

- The largest mRNA, (which is longer than the viral genome), is used to make the new copies of the genome and to make the capsid core protein and the viral RNA-dependant-DNA-polymerase.

- Assembly

- These four viral transcripts undergo additional processing and go on to form progeny virions which are released from the cell or returned to the nucleus and re-cycled to produce even more copies.[30][41]

- Release

- The long mRNA is then transported back to the cytoplasm where the virion P protein synthesizes DNA via its reverse transcriptase activity.

Transactivated genes

HBV has the ability to transactivate FAM46A.[42]

See also

- Hepatitis B vaccine

- Nucleoside analogues

- Oncovirus (cancer virus)

References

- ↑ Merriam-Webster's Collegiate Dictionary, ELEVENTH EDITION, (C)2007, page 581

- ↑ Hunt, Richard (2007-11-21). "Hepatitis viruses". University of Southern California, Department of Pathology and Microbiology. Retrieved 2008-03-13.

- 1 2 Hassan MM, Li D, El-Deeb AS, Wolff RA, Bondy ML, Davila M, Abbruzzese JL (2008). "Association between hepatitis B virus and pancreatic cancer". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 26 (28): 4557–62. PMC 2562875

. PMID 18824707. doi:10.1200/JCO.2008.17.3526.

. PMID 18824707. doi:10.1200/JCO.2008.17.3526. - ↑ Schwalbe M, Ohlenschläger O, Marchanka A, Ramachandran R, Häfner S, Heise T, Görlach M (2008). "Solution structure of stem-loop alpha of the hepatitis B virus post-transcriptional regulatory element". Nucleic Acids Research. 36 (5): 1681–9. PMC 2275152

. PMID 18263618. doi:10.1093/nar/gkn006.

. PMID 18263618. doi:10.1093/nar/gkn006. - ↑ Mason, W.S.; et al. (2008-07-08). "00.030. Hepadnaviridae". ICTVdB Index of Viruses. International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Retrieved 2009-03-13.

- ↑ Dupinay T, et al. (November 2013). "Discovery of naturally occurring transmissible chronic hepatitis B virus infection among Macaca fascicularis from Mauritius Island.". Hepatology,. 58 (5). pp. 1610–1620. PMID 23536484. doi:10.1002/hep.26428.

- 1 2 Hundie GB, Stalin Raj V, Gebre Michael D, Pas SD, Koopmans MP, Osterhaus AD, Smits SL, Haagmans BL (2016) A novel hepatitis B virus subgenotype D10 circulating in Ethiopia. J Viral Hepat doi: 10.1111/jvh.12631.

- 1 2 Kramvis A, Kew M, François G (2005). "Hepatitis B virus genotypes". Vaccine. 23 (19): 2409–23. PMID 15752827. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.10.045.

- ↑ Magnius LO, Norder H (1995). "Subtypes, genotypes and molecular epidemiology of the hepatitis B virus as reflected by sequence variability of the S-gene". Intervirology. 38 (1–2): 24–34. PMID 8666521.

- ↑ Ghosh S, Banerjee P, Deny P, Mondal RK, Nandi M, Roychoudhury A, Das K, Banerjee S, Santra A, Zoulim F, Chowdhury A, Datta S (2013). "New HBV subgenotype D9, a novel D/C recombinant, identified in patients with chronic HBeAg-negative infection in Eastern India". J Viral Hepat. 20 (3): 209–18. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2893.2012.01655.x.

- ↑ Drexler JF, Geipel A, König A, Corman VM, van Riel D, Leijten LM, Bremer CM, Rasche A, Cottontail VM, Maganga GD, Schlegel M, Müller MA, Adam A, Klose SM, Carneiro AJ, Stöcker A, Franke CR, Gloza-Rausch F, Geyer J, Annan A, Adu-Sarkodie Y, Oppong S, Binger T, Vallo P, Tschapka M, Ulrich RG, Gerlich WH, Leroy E, Kuiken T, Glebe D, Drosten C (2013). "Bats carry pathogenic hepadnaviruses antigenically related to hepatitis B virus and capable of infecting human hepatocytes". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 110 (40): 16151–6. Bibcode:2013PNAS..11016151D. PMC 3791787

. PMID 24043818. doi:10.1073/pnas.1308049110.

. PMID 24043818. doi:10.1073/pnas.1308049110. - ↑ Zuckerman AJ (1996). Baron S; et al., eds. Hepatitis Viruses. In: Baron's Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). Univ of Texas Medical Branch. ISBN 0-9631172-1-1.

- ↑ "WHO | Hepatitis B". www.who.int. Archived from the original on 2015-07-10. Retrieved 2015-07-12.

- ↑ Locarnini S (2004). "Molecular virology of hepatitis B virus". Semin. Liver Dis. 24 (Suppl 1): 3–10. PMID 15192795. doi:10.1055/s-2004-828672.

- ↑ Howard CR (1986). "The biology of hepadnaviruses". J. Gen. Virol. 67 (7): 1215–35. PMID 3014045. doi:10.1099/0022-1317-67-7-1215.

- ↑ Guo GH, Tan DM, Zhu PA, Liu F (February 2009). "Hepatitis B virus X protein promotes proliferation and upregulates TGF-beta1 and CTGF in human hepatic stellate cell line, LX-2". Hbpd Int. 8 (1): 59–64. PMID 19208517. Archived from the original on 2009-04-13.

- ↑ Benhenda S, Ducroux A, Rivière L, Sobhian B, Ward MD, Dion S, Hantz O, Protzer U, Michel ML, Benkirane M, Semmes OJ, Buendia MA, Neuveut C (2013). "Methyltransferase PRMT1 is a binding partner of HBx and a negative regulator of hepatitis B virus transcription". Journal of Virology. 87 (8): 4360–71. PMC 3624337

. PMID 23388725. doi:10.1128/JVI.02574-12.

. PMID 23388725. doi:10.1128/JVI.02574-12. - ↑ Chai N, Chang HE, Nicolas E, Han Z, Jarnik M, Taylor J (2008). "Properties of subviral particles of hepatitis B virus". Journal of Virology. 82 (16): 7812–7. PMC 2519590

. PMID 18524834. doi:10.1128/JVI.00561-08.

. PMID 18524834. doi:10.1128/JVI.00561-08. - 1 2 van Hemert FJ, van de Klundert MA, Lukashov VV, Kootstra NA, Berkhout B, Zaaijer HL (2011). "Protein X of hepatitis B virus: origin and structure similarity with the central domain of DNA glycosylase". PLoS ONE. 6 (8): e23392. PMC 3153941

. PMID 21850270. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0023392.

. PMID 21850270. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0023392. - ↑ Lin B, Anderson DA (2000). "A vestigial X open reading frame in duck hepatitis B virus". Intervirology. 43 (3): 185–90. PMID 11044813. doi:10.1159/000025037.

- ↑ Osiowy C, Giles E, Tanaka Y, Mizokami M, Minuk GY (2006). "Molecular evolution of hepatitis B virus over 25 years". Journal of Virology. 80 (21): 10307–14. PMC 1641782

. PMID 17041211. doi:10.1128/JVI.00996-06.

. PMID 17041211. doi:10.1128/JVI.00996-06. - ↑ Zhou Y, Holmes EC (August 2007). "Bayesian estimates of the evolutionary rate and age of hepatitis B virus". J. Mol. Evol. 65 (2): 197–205. PMID 17684696. doi:10.1007/s00239-007-0054-1.

- ↑ Paraskevis D, Magiorkinis G, Magiorkinis E, Ho SY, Belshaw R, Allain JP, Hatzakis A (2013). "Dating the origin and dispersal of hepatitis B virus infection in humans and primates". Hepatology. 57 (3): 908–16. PMID 22987324. doi:10.1002/hep.26079.

- ↑ Littlejohn, M; Locarnini, S; Yuen, L (4 January 2016). "Origins and Evolution of Hepatitis B Virus and Hepatitis D Virus.". Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in medicine. 6 (1): a021360. PMID 26729756. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a021360.

- ↑ Rasche, A; Souza, BF; Drexler, JF (February 2016). "Bat hepadnaviruses and the origins of primate hepatitis B viruses.". Current Opinion in Virology. 16: 86–94. PMID 26897577. doi:10.1016/j.coviro.2016.01.015.

- ↑ Kay A, Zoulim F (2007). "Hepatitis B virus genetic variability and evolution". Virus Res. 127 (2): 164–76. PMID 17383765. doi:10.1016/j.virusres.2007.02.021.

- ↑ Doitsh G, Shaul Y (2004). "Enhancer I predominance in hepatitis B virus gene expression". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 24 (4): 1799–808. PMC 344184

. PMID 14749394. doi:10.1128/mcb.24.4.1799-1808.2004.

. PMID 14749394. doi:10.1128/mcb.24.4.1799-1808.2004. - ↑ Antonucci TK, Rutter WJ (1989). "Hepatitis B virus (HBV) promoters are regulated by the HBV enhancer in a tissue-specific manner". Journal of Virology. 63 (2): 579–83. PMC 247726

. PMID 2536093.

. PMID 2536093. - ↑ Huan B, Siddiqui A (1993). "Regulation of hepatitis B virus gene expression". Journal of Hepatology. 17 Suppl 3: S20–3. PMID 8509635. doi:10.1016/s0168-8278(05)80419-2.

- 1 2 Beck J, Nassal M (2007). "Hepatitis B virus replication". World J. Gastroenterol. 13 (1): 48–64. PMC 4065876

. PMID 17206754. doi:10.3748/wjg.v13.i1.48.

. PMID 17206754. doi:10.3748/wjg.v13.i1.48. - ↑ Bouchard MJ, Schneider RJ (2004). "The enigmatic X gene of hepatitis B virus". Journal of Virology. 78 (23): 12725–34. PMC 524990

. PMID 15542625. doi:10.1128/JVI.78.23.12725-12734.2004.

. PMID 15542625. doi:10.1128/JVI.78.23.12725-12734.2004. - ↑ Smith GJ, Donello JE, Lück R, Steger G, Hope TJ (1998). "The hepatitis B virus post-transcriptional regulatory element contains two conserved RNA stem-loops which are required for function". Nucleic Acids Research. 26 (21): 4818–27. PMC 147918

. PMID 9776740. doi:10.1093/nar/26.21.4818.

. PMID 9776740. doi:10.1093/nar/26.21.4818. - ↑ Flodell S, Schleucher J, Cromsigt J, Ippel H, Kidd-Ljunggren K, Wijmenga S (2002). "The apical stem-loop of the hepatitis B virus encapsidation signal folds into a stable tri-loop with two underlying pyrimidine bulges". Nucleic Acids Research. 30 (21): 4803–11. PMC 135823

. PMID 12409471. doi:10.1093/nar/gkf603.

. PMID 12409471. doi:10.1093/nar/gkf603. - ↑ Olinger CM, Jutavijittum P, Hübschen JM, Yousukh A, Samountry B, Thammavong T, Toriyama K, Muller CP (2008). "Possible new hepatitis B virus genotype, southeast Asia". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 14 (11): 1777–80. PMC 2630741

. PMID 18976569. doi:10.3201/eid1411.080437.

. PMID 18976569. doi:10.3201/eid1411.080437. - ↑ Kurbanov F, Tanaka Y, Kramvis A, Simmonds P, Mizokami M (2008). "When should 'I' consider a new hepatitis B virus genotype?". Journal of Virology. 82 (16): 8241–2. PMC 2519592

. PMID 18663008. doi:10.1128/JVI.00793-08.

. PMID 18663008. doi:10.1128/JVI.00793-08. - ↑ Hernández S, Venegas M, Brahm J, Villanueva RA (2014). "Full-genome sequence of a hepatitis B virus genotype f1b clone from a chronically infected Chilean patient (2014)". Genome Announc. 2 (5): e01075–14. PMC 4208329

. PMID 25342685. doi:10.1128/genomeA.01075-14.

. PMID 25342685. doi:10.1128/genomeA.01075-14. - ↑ Palumbo E (2007). "Hepatitis B genotypes and response to antiviral therapy: a review". American Journal of Therapeutics. 14 (3): 306–9. PMID 17515708. doi:10.1097/01.pap.0000249927.67907.eb.

- ↑ Mahtab MA, Rahman S, Khan M, Karim F (2008). "Hepatitis B virus genotypes: an overview". Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International. 7 (5): 457–64. PMID 18842489.

- ↑ Cavinta L, Sun J, May A, et al. (June 2009). "A new isolate of hepatitis B virus from the Philippines possibly representing a new subgenotype C6". J. Med. Virol. 81 (6): 983–7. PMID 19382274. doi:10.1002/jmv.21475.

- ↑ Lusida M.I.; Nugrahaputra V.E.; Soetjipto Handajani R.; Nagano-Fujii M.; Sasayama M.; Utsumi T.; Hotta H. (2008). "Novel subgenotypes of hepatitis B virus genotypes C and D in Papua, Indonesia". J. Clin. Microbiol. 46 (7): 2160–2166. PMC 2446895

. PMID 18463220. doi:10.1128/JCM.01681-07.

. PMID 18463220. doi:10.1128/JCM.01681-07. - ↑ Bruss V (2007). "Hepatitis B virus morphogenesis". World J. Gastroenterol. 13 (1): 65–73. PMC 4065877

. PMID 17206755.

. PMID 17206755. - ↑ "Fam46A (Protein Coding)". GeneCards. GeneCards. Retrieved 18 February 2015.