Harry Lauder

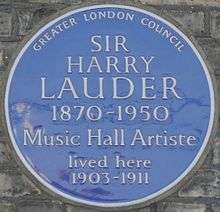

Sir Henry "Harry" Lauder (/ˈlɔːdər/; 4 August 1870 – 26 February 1950)[1] was a Scottish singer and comedian popular in both the English music hall and vaudevillian theatre tradition; he achieved international success.

He was described by Sir Winston Churchill as "Scotland's greatest ever ambassador".[2][3][4] He became a familiar worldwide figure promoting images like the kilt and the cromach (walking stick) to huge acclaim, especially in America. Other songs followed, including "Roamin' in the Gloamin", "A Wee Deoch-an-Doris", "The End of the Road" and, a particularly big hit for him, "I Love a Lassie".

By 1911 Lauder had become the highest-paid performer in the world, and was the first Scottish artist to sell a million records. He raised vast amounts of money for the war effort during the First World War, for which he was knighted in 1919. He went into semi-retirement in the mid-1930s, but briefly emerged to entertain troops in the Second World War. By the late 1940s he was suffering from long periods of ill-health and died in Scotland in 1950.

Biography

Early life

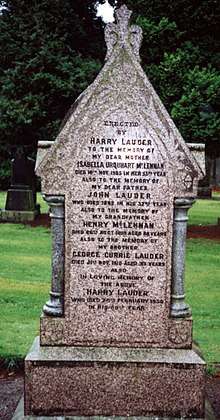

Lauder was born on 4 August 1870 in his maternal grandfather's house in Portobello, Edinburgh, Scotland,[5] the eldest of seven children.[6] His father, John Lauder, was a descendant of the feudal barons the Lauders of the Bass;[7] and his mother, Isabella Urquhart Macleod née McLennan, was born in Arbroath to a family from the Black Isle.[8] Lauder's father moved to Newbold, Derbyshire in early 1882 to take up a job designing china, but died on 20 April. Isabella, left with little more than John's life insurance proceeds of £15, moved the family to Arbroath.[9] To finance his education beyond age 11, Harry worked part time at a flax mill. In 1884 the family went to Hamilton, South Lanarkshire to live with Isabella's brother, who found him employment at Eddlewood Colliery at ten shillings per week; he kept this job for a decade.[10]

Marriage and early career

On 19 June 1891 Lauder married Ann Vallance, daughter of a colliery manager in Hamilton.[5] Lauder often sang to the miners in Hamilton, who encouraged him to perform in local music halls. While singing in nearby Larkhall, he received 5 shillings—the first time he was paid for singing. He received further engagements including a weekly "go-as-you please" night held by Mrs. Christina Baylis at her Scotia Music Hall/Metropole Theatre in Glasgow. She advised him to gain experience by touring music halls around the country with a concert party, which he did. The tour allowed him to quit the coal mines and become a professional singer. Lauder concentrated his repertoire on comedic routines and songs of Scotland and Ireland.[11]

By 1894 he had turned professional and performed local characterisations at small, Scottish and northern English music halls, but had ceased the repertoire by 1900. In March of that year, Lauder travelled to London and reduced the heavy dialect of his act which according to a biographer, Dave Russell, "handicapped Scottish performers in the metropolis". He was an immediate success at the Charing Cross Music Hall and the London Pavilion, venues at which the theatrical paper The Era thought he generated "[a] great furore" among his audiences with three of his self-composed songs.[1]

He was initiated a Freemason on 28 January 1897 in Lodge Dramatic, No.571, and remained an active Freemason for the rest of his life.[12]

Career peak years; 1900–1920

In 1905 Lauder's success in leading the Howard & Wyndham pantomime at the Theatre Royal, Glasgow, for which he wrote I Love a Lassie, made him a national star, and he obtained contracts with Sir Edward Moss and others. Lauder then made a switch from music hall to variety theatre and undertook a tour of America in 1907. The following year, he performed a private show before Edward VII at Sandringham, and in 1911, he again toured the United States where he commanded $1,000 a night. In 1912, he was top of the bill at Britain's first ever Royal Command Performance, in front of King George V, organised by Alfred Butt.[13][14] Lauder undertook world tours extensively during his forty-year career, including 22 trips to the United States—for which he had his own railroad train, the Harry Lauder Special, and made several trips to Australia, where his brother John had emigrated. Lauder was, at one time, the highest-paid performer in the world, making the equivalent of £12,700 a night plus expenses.[15] He was paid £1125 for an engagement at the Glasgow Pavilion Theatre in 1913 and was later considered by the press to earn one of the highest weekly salaries by a theatrical performer during the pre-war period.[1] In January 1914 he embarked on a tour that included the United States, Australia, New Zealand and Canada.[16] During the First World War Lauder promoted recruitment into the services and starred in many concerts for troops at home and on the western front. His entertainment activities were made poignant by the death in action of his son at the end of 1916.

First World War

The First World War broke out while Lauder was touring Australia.[17] During this war, he led successful charity fundraising efforts, organised a recruitment tour of music halls, and entertained troops in France with a piano. Through his efforts in organising concerts and fundraising appeals he established the charity, the Harry Lauder Million Pound Fund,[18] for maimed Scottish soldiers and sailors to help servicemen return to health and civilian life,[19] and for these many services he was knighted in May 1919.[20][21]

In 1915 he wrote "I know that I am voicing the sentiment of thousands and thousands of people when I say that we must retaliate in every possible way regardless of cost. If these German savages want savagery, let them have it".[22]

His only son John, a Cambridge University-educated Captain in the 8th Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, was killed in action on 28 December 1916 at Pozières.[23][24] Nonetheless, with his wife's encouragement Lauder returned to the stage three days after learning of John's death.[17] He wrote the song "The End of the Road" (published as a collaboration with the American William Dillon, 1924) in the wake of John's death, and built a monument for him in the private Lauder cemetery in Glenbranter. (John Lauder was buried in the war cemetery at Ovillers, France). Winston Churchill wrote that Lauder, "... by his inspiring songs and valiant life, rendered measureless service to the Scottish race and to the British Empire."[25]

Later years

Lady Lauder died on 31 July 1927, at 54, a week after an operation.[26] She was buried next to John's memorial in the Lauder cemetery alongside her parents. Lauder's niece, Margaret (1900–1966), became his secretary and cared for him up until his death.

After the First World War, Lauder continued to tour the variety theatre circuits; his last tour was in North America in 1932. He made plans for a house at Strathaven, to be called Lauder Ha'.[27] He was semi-retired in the mid-1930s, until his final retirement was announced in 1935. He briefly emerged from retirement to entertain troops during the war and make wireless broadcasts with the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra.

Lauder's understanding of life, its pathos and joys, earned him his popularity. Beniamino Gigli commended his singing voice and clarity. Lauder usually performed in full Highland regalia—kilt, sporran, tam o' shanter, and twisted walking stick—and sung Scottish-themed songs, including Roamin' in the Gloamin'.

His works

.jpg)

Sir Harry wrote most of his own songs, favourites of which were Roamin' In The Gloamin', I Love a Lassie, A Wee Deoch-an-Doris, and The End of the Road, which is used by Birmingham City Football Club as their club anthem. He starred in three British films: Huntingtower (1927), Auld Lang Syne (1929) and The End of the Road (1936). He also appeared in a test film for the Photokinema sound-on-disc process in 1921. This film is part of the UCLA Film and Television Archive collection; however, the disc is missing. In 1914, Lauder appeared in 14 Selig Polyscope experimental short sound films.[28] In 1907, he appeared in a short film singing "I Love a Lassie" for British Gaumont.[29] The British Film Institute has several reels of what appears to be an unreleased film All for the Sake of Mary (c. 1920) co-starring Effie Vallance and Harry Vallance.[30]

He wrote a number of books, which ran into several editions, including Harry Lauder at Home and on Tour (1912), A Minstrel in France (1918),[31] Between You and Me (1919), Roamin' in the Gloamin' (1928 autobiography),[32] My Best Scotch Stories (1929), Wee Drappies (1931) and Ticklin' Talks (circa 1932).

Recordings

Lauder made his first recordings, resulting in nine selections, for the Gramophone & Typewriter company early in 1902. [33] He continued to record for Gramophone until the middle of 1905, most recordings appearing on the Gramophone label, but others on Zonophone.[33] He then recorded fourteen selections for Pathé Records June 1906.[33] Two months later he was back at Gramophone, and performed for them in several sessions through 1908.[33] That year he made several two and four-minute cylinders for Edison Records. Next year he recorded for Victor in New York. He continued to make some cylinders for Edison, but was primarily associated with His Master’s Voice and Victor.[33] In 1910 Victor introduced a mid-priced purple-label series, the first twelve issues of which were by Harry Lauder. [34] In 1927 Victor promoted Lauder recordings to their Red Seal imprint, the only comedic performer to appear on the label primarily associated with operatic celebrities.[33][35] Lauder is one of just three artists shown on Victor’s black, purple, blue, and Red Seal records (the others being Lucy Isabelle Marsh and Reinald Werrenrath).[36] His final recordings were made in 1940, but Lauder records were included issued in the new format as current material when RCA Victor introduced the 45rpm record.[33][35]

Portraits

Lauder is credited with giving the then 21-year-old portrait artist Cowan Dobson his opening into society by commissioning him, in 1915, to paint his portrait. This was considered to be so outstanding that another commission came the following year, to paint his son Captain John Lauder, and again another commission in 1921 to paint Sir Harry's wife,[37] the latter portrait being after the style of John Singer Sargent. These three portraits remain in the family's possession. The same year, Scottish artist James McBey painted another portrait of Sir Harry, today in the Glasgow Museums.[38] In the tradition of the famous British magazine Vanity Fair, there appeared numerous caricatures of Sir Harry Lauder. Of the more notable is one by Al Frueh (1880–1968) in 1911 and published in 1913 in the New York World magazine,[39] another by Henry Mayo Bateman, now in London's National Gallery,[40] and one of 1926 by Alick P.F.Ritchie, for Players Cigarettes, today in the London National Portrait Gallery (ref:NPG D2675).[41]

Death

Lauder leased the Glenbranter estate in Argyll to the Forestry Commission and spent his last years at Lauder Ha (or Hall), his Strathaven home, where he died on 26 February 1950, aged 79.[5][42][43] His funeral was held at Cadzow church in Hamilton on 2 March.[44] It was widely reported, notably by Pathé newsreels.[45] One of the chief mourners was the Duke of Hamilton, a close family friend, who led the funeral procession through Hamilton, and read The Lesson. Wreaths were sent from the Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother, and Winston Churchill. Lauder was interred with the rest of his family at Bent Cemetery in Hamilton.[46]

Posthumous

Websites carry much of his material and the Harry Lauder Collection, amassed by entertainer Jimmy Logan, was bought for the nation and donated to the University of Glasgow.[47] When the A199 Portobello bypass opened, it was named the Sir Harry Lauder Road.[48][49]

On 28 July 1987, the Lord Provost of Edinburgh hosted a luncheon at the Edinburgh City Chambers to commemorate the 60th Anniversary of Lauder receiving the Freedom of the City. On 4 August 2001 Gregory Lauder-Frost opened the Sir Harry Lauder Memorial Garden at Portobello Town Hall.[50] Saltire/BBC2 TV (Scotland) aired a documentary, Something About Harry, on 30 November 2005. On 29 September 2007, Lauder-Frost rededicated the Burslem Golf Course & Club at Stoke-on-Trent, which had been formally opened exactly a century before by Harry Lauder.[51]

In the 1990s, samples of recordings of Lauder were used on two tracks recorded by the Scottish folk/dance music artist Martyn Bennett.[52] The Corkscrew Hazel ornamental cultivar of common hazel (Corylus avellana) is sometimes known as Harry Lauder's Walking Stick, in reference to the crooked walking stick Lauder often carried.[53]

Selected filmography

- Huntingtower (1927)

- Auld Lang Syne (1929)

- The End of the Road (1936)

References

- 1 2 3 Russell, Dave. "Lauder, Sir Henry (1870–1950)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004, online edition, January 2011, accessed 27 April 2014 (subscription required)

- ↑ "Sir Harry Lauder: 1870–1950". University of Glasgow. Archived from the original on 15 May 2015.

- ↑ "Sir Harry Lauder". Time. 10 March 1930. Retrieved 14 August 2008.

- ↑ Lauder-Frost, Gregory. "Biographical Notes on Sir Harry Lauder". Electric Scotland. Retrieved 20 February 2011.

- 1 2 3 "Hall of Fame A-Z. Sir Harry Lauder (1870-1950)". National Records of Scotland. Retrieved 3 July 2017.

- ↑ Wallace, 1988, p.16.

- ↑ Lauder, Sir Harry, Roamin' in the Gloamin, Hutchinson & Co., London, 1927, p.26.

- ↑ "The Ancestry of Sir Harry Lauder" in The Scottish Genealogist, vol.liii, no.2, Edinburgh, June 2006, pp.74–87. ISSN 0300-337X

- ↑ Wallace, 1988, p.18.

- ↑ Wallace, 1988, p.21.

- ↑ "Sir Harry Lauder: 1870–1950". Special Collections. University of Glasgow.

- ↑ Famous Scottish Freemasons. Published by the Grand Lodge of Scotland 2010. ISBN 978-0-9560933-8-7

- ↑ "Music Hall Gala. Visit of the King to Palace Theatre". The Glasgow Herald. 1 August 1927. p. 11. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

- ↑ Fleming, Craig (4 December 2012). "Harry’s wages were cut... by royal command!". Blackpool Gazette. Retrieved 3 July 2017.

- ↑ "Harry Lauder, coming to a ringtone near you". The Sunday Times. 24 July 2005.

- ↑ "Harry Lauder’s Tour. Dates and Prospects. Interesting Interview". The Southland Times (17556). 21 January 1914. Retrieved 3 July 2017.

- 1 2 Brocklehurst, Steven (12 November 2014). "World War One at Home: How Harry Lauder's war tragedy spurred him on". BBC News. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

- ↑ Scotland, National Archives of. "NAS Catalogue - catalogue record". catalogue.nrscotland.gov.uk.

- ↑ Wallace, William, Harry Lauder in the Limelight, Lewes, Sussex, 1988, p.49, ISBN 0-86332-312-X

- ↑ "Central Chancery of the Orders of Knighthood". Edinburgh Gazette (13440). 2 May 1919. p. 1591. Retrieved 3 July 2017.

- ↑ Wallace, 1988, p.55.

- ↑ "Impassioned Address By Harry", Arbroath Herald and Advertiser For The Montrose Burghs, 11 June 1915 – via British Newspaper Archive, (Subscription required (help))

- ↑ "Interesting Address from Harry Lauder". The McGill Daily. 26 November 1917. pp. 1–2. Retrieved 3 July 2017.

- ↑ Manchester, Reading Room. "Casualty Details". www.cwgc.org.

- ↑ Winston S. Churchill, The Second World War – Volume III, p.530

- ↑ "Death of Lady Lauder". The Glasgow Herald. 1 August 1927. p. 11. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

- ↑ "Section and South elevation of Lauder Ha', the "proposed house at Strathaven for Sir Harry Lauder".". Canmore. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

- ↑ "Silent Era : Progressive Silent Film List". www.silentera.com.

- ↑ "SilentEra entry". Archived from the original on 21 January 2012.

- ↑ "All for the Sake of Mary (1920)".

- ↑ "A Minstrel in France. By Harry Lauder. (Melrose. 78. 6d. net.)". The Spectator. 12 October 1918. p. 21. Retrieved 3 July 2017.

- ↑ Jack, Ian (27 May 2006). "From bad to good". The Guardian. Retrieved 3 July 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Andrews, Frank (2005). Hoffman, Frank, ed. Encyclopedia of Recorded Sound. Routledge. p. 595. ISBN 0-415-93835-X.

- ↑ Gracyk, Tim (2000). Popular American Recording Pioneers 1895–1925. New York: The Haworth Press. p. 231. ISBN 1-56024-993-5.

- 1 2 Andrews, Frank (2005). Hoffman, Frank, ed. Encyclopedia of Recorded Sound. Routledge. p. 449. ISBN 0-415-93835-X.

- ↑ Gracyk, Tim (2000). Popular American Recording Pioneers 1895–1925. New York: The Haworth Press. p. 352. ISBN 1-56024-993-5.

- ↑ Morrison, McChlery & Co.,Glasgow, Catalogue of the Furnishings of Lauder Hall, Strathaven, May 1966, p.13.

- ↑ "Sir Harry Lauder (1870–1950) - Art UK Art UK - Discover Artworks Sir Harry Lauder (1870–1950)".

- ↑ "Caricature and Cartoon in Twentieth-Century America: Caroline and Erwin Swann Foundation for Caricature and Cartoon (Prints and Photographs Reading Room, Library of Congress)". www.loc.gov.

- ↑ "Sir Harry Lauder by Henry Mayo Bateman - National Galleries of Scotland". National Galleries of Scotland.

- ↑ "Sir Harry Lauder". London National Portrait Gallery. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

- ↑ "Death of Sir Harry Lauder. World Fame as Scots Singer". The Glasgow Herald. 27 February 1950. p. 4. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

- ↑ "From the archives. Sir Harry Lauder dies". The Guardian. 27 February 2009. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

- ↑ "Lauder cortege of 200 cars". The Glasgow Herald. 3 March 1950. p. 7. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

- ↑ Gilchrist, Jim. "Selected Originals - Funeral Of Sir Harry…". Pathé News. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

- ↑ Wallace (1988), p. 93.

- ↑ Marshalsay, Karen. "Sir Harry Lauder (1870-1950)". www.arts.gla.ac.uk.

- ↑ Mclean, David (27 May 2014). "Lost Edinburgh: Sir Harry Lauder". The Scotsman. Retrieved 3 July 2017.

- ↑ "List of Public Roads Q – Z" (PDF). p. 37. Retrieved 30 August 2007.

- ↑ The Portobello Reporter, Autumn 2001 edition

- ↑ The Sentinel (newspaper), Stoke-on-Trent, 4 October 2007, p. 47 (includes photo).

- ↑ Gilchrist, Jim (22 March 2012). "Folk, jazz etc: Fond memories of the ‘techno piper’ and a man who taught us so much". The Scotsman. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

- ↑ "Harry Lauder's Walkingstick". University of Arkansas. 30 January 2015. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

Further reading

- Great Scot!: the life story of Sir Harry Lauder, legendary laird of the music hall. by Gordon Irving, London, 1968 (ISBN 0-09-089070-1).

- Harry Lauder in the Limelight by William Wallace, Lewes, Sussex, 1988, (ISBN 0-86332-312-X), which has a foreword and extensive notes by Sir Harry's great-nephew, Gregory Lauder-Frost.

- The Sunday Times (Scottish edition), 24 July 2005, article: "Harry Lauder, coming to a ringtone near you", by David Stenhouse.

- The Ancestry of Sir Harry Lauder, in The Scottish Genealogist, Edinburgh, June 2006, Vol. 53, No. 2, ISSN 0300-337X

- A Minstrel in France, Hearst's International Book Company, London, 1918, by Harry Lauder about the death of his son.

- Lauder-Frost, Gregory. "Biographical Notes on Sir Harry Lauder". Retrieved 30 August 2007.

- Roamin' in the Gloamin (Autobiography) by Sir Harry Lauder, (London, 1928), reprinted without the photos, London, 1976, (ISBN 0-7158-1176-2)

- "The Theatre Royal: Entertaining A Nation" by Graeme Smith, Glasgow, 2008

External links

Media related to Harry Lauder at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Harry Lauder at Wikimedia Commons- Harry Lauder on IMDb

- Harry Lauder at BFI Database

- A Celebration of Sir Harry Lauder An Archive Of All Things Sir Harry Lauder

- Works by Harry Lauder at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Harry Lauder at Internet Archive

- Harry Lauder cylinder recordings, from the Darrell Baker Collection Cylinder Preservation and Digitization Project at the University of California, Santa Barbara Library.

- Discography of Harry Lauder on Victor Records from the Encyclopedic Discography of Victor Recordings (EDVR)

- Scottish Theatre Archive, Glasgow

- THE MYSTERIOUS DEATH OF CAPTAIN JOHN LAUDER (Ed Dixon)