Henry Cabot Lodge Jr.

| Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| Personal Representative of the President to the Holy See | |

|

In office June 5, 1970 – July 6, 1977 | |

| President |

Richard Nixon Gerald Ford Jimmy Carter |

| Preceded by | Harold Tittmann (Acting) |

| Succeeded by | David Walters |

| U.S. Ambassador to West Germany | |

|

In office May 27, 1968 – January 14, 1969 | |

| President | Lyndon B. Johnson |

| Preceded by | George C. McGhee |

| Succeeded by | Kenneth Rush |

| U.S. Ambassador to South Vietnam | |

|

In office August 25, 1965 – April 25, 1967 | |

| President | Lyndon B. Johnson |

| Preceded by | Maxwell D. Taylor |

| Succeeded by | Ellsworth Bunker |

|

In office August 26, 1963 – June 28, 1964 | |

| President |

John F. Kennedy Lyndon B. Johnson |

| Preceded by | Frederick Nolting |

| Succeeded by | Maxwell D. Taylor |

| 3rd U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations | |

|

In office January 26, 1953 – September 3, 1960 | |

| President | Dwight D. Eisenhower |

| Preceded by | Warren Austin |

| Succeeded by | Jerry Wadsworth |

| United States Senator from Massachusetts | |

|

In office January 3, 1947 – January 3, 1953 | |

| Preceded by | David I. Walsh |

| Succeeded by | John F. Kennedy |

|

In office January 3, 1937 – February 3, 1944 | |

| Preceded by | Marcus A. Coolidge |

| Succeeded by | Sinclair Weeks |

| Member of the Massachusetts House of Representatives from the 15th Essex district | |

|

In office 1932–1936 | |

| Preceded by | Herbert Wilson Porter |

| Succeeded by | Russell P. Brown |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

July 5, 1902 Nahant, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Died |

February 27, 1985 (aged 82) Beverly, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse(s) | Emily Sears (1926–1985) |

| Children | 2 (including George) |

| Parents | George Cabot Lodge |

| Education | Harvard University (BA) |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/branch |

|

| Rank |

|

| Battles/wars | World War II |

Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. (July 5, 1902 – February 27, 1985) sometimes referred to as Henry Cabot Lodge II,[1] was a Republican United States Senator from Massachusetts and a U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, South Vietnam, West Germany, and the Holy See (as Presidential Representative). He was the Republican nominee for Vice President in the 1960 presidential election.

Early life

Lodge was born in Nahant, Massachusetts. His father was George Cabot Lodge, a poet and politician, through whom he was a grandson of Senator Henry Cabot Lodge, great-great-grandson of Senator Elijah H. Mills, and great-great-great-grandson of Senator George Cabot. Through his mother, Mathilda Elizabeth Frelinghuysen (Davis), he was a great-grandson of Senator Frederick Theodore Frelinghuysen,[2] and a great-great-grandson of Senator John Davis. He had two siblings: John Davis Lodge (1903–1985), also a politician, and Helena Lodge de Streel (1905-1998).[3][4]

Lodge attended St. Albans School and graduated from Middlesex School. In 1924, he graduated cum laude from Harvard University, where he was a member of the Hasty Pudding and the Fox Club.[5]

Political career

Lodge worked in the newspaper business from 1924–1931. He was elected in 1932, and served in the Massachusetts House of Representatives 1933 to 1936. [6]

First U.S. Senate career

In November 1936, Lodge was elected to the United States Senate as a Republican, defeating Democrat James Michael Curley. He served from January 1937 to February 1944.

World War II

Lodge served with distinction during the war, rising to the rank of lieutenant colonel. During the war he saw two tours of duty. The first was in 1942 while he was also serving as a U.S. Senator. The second was in 1944–5 after he resigned from the Senate.

The first period was a continuation of Lodge's longtime service as an Army Reserve Officer. Lodge was a major in the 1st Armored Division. That tour ended in July 1942, when President Franklin D. Roosevelt ordered congressmen serving in the military to resign one of the two positions, and Lodge, who chose to remain in the Senate, was ordered by Secretary of War Henry Stimson to return to Washington.[7]

After returning to Washington and winning re-election in November 1942, Lodge went to observe allied troops serving in Egypt and Libya,[8] and in that position, he was on hand for the British retreat from Tobruk.[7]

Lodge served the first year of his new Senate term but then resigned his Senate seat on February 3, 1944 in order to return to active duty,[9] the first U.S. Senator to do so since the Civil War[10] He saw action in Italy and France.

In the fall of 1944, Lodge single-handedly captured a four-man German patrol.[11]

At the end of the war, in 1945, he used his knowledge of the French language and culture, gained from attending school in Paris to aid Jacob L. Devers, the commander of the Sixth United States Army Group, to coordinate activities with the Army Group's First Army commander, Jean de Lattre de Tassigny, and then carry out surrender negotiations with German forces in western Austria.

Lodge was decorated with the French Legion of Honor and Croix de Guerre with palm.[12] His American decorations included the Legion of Merit and the Bronze Star Medal.

After the war, Lodge returned to Massachusetts and resumed his political career. He continued his status as an Army Reserve officer and rose to the rank of major general.[13][14][15]

Return to Senate and the drafting of Eisenhower

In 1946 Lodge defeated Democratic Senator David I. Walsh and returned to the Senate. He soon emerged as a spokesman for the moderate, internationalist wing of the Republican Party. In late 1951, Lodge helped persuade General Dwight D. Eisenhower to run for the Republican presidential nomination. When Eisenhower finally consented, Lodge served as his campaign manager and played a key role in helping Eisenhower to win the nomination over Senator Robert A. Taft of Ohio, the candidate of the party's conservative faction.

In March 1950, Lodge sat on a subcommittee of the Government Operations Committee, chaired by Democratic Senator Millard Tydings, which looked into Senator Joseph McCarthy's list of possibly communist State Department employees. Lodge argued in hearings that Tydings demonized McCarthy and whitewashed McCarthy's supposed discovery of security leaks at the State Department. Lodge told Tydings:

Mr. Chairman, this is the most unusual procedure I have seen in all the years I have been here. Why cannot the senator from Wisconsin get the normal treatment and be allowed to make his statement in his own way,... and not be pulled to pieces before he has had a chance to offer one single consecutive sentence.... I do not understand what kind of game is being played here.[16]

In July 1950, the record of the committee hearing was printed, and Lodge was outraged to find that 35 pages were not included.[17] Lodge noted that his objections to the conduct of the hearing and his misgivings about the inadequacy of vetting suspected traitors were missing,[18] and that the edited version read as if all committee members agreed that McCarthy was at fault and that there was no Communist infiltration of the State Department.[19] Lodge stated "I shall not attempt to characterize these methods of leaving out of the printed text parts of the testimony and proceedings... because I think they speak for themselves." Lodge soon fell out with McCarthy and joined the effort to reduce McCarthy's influence.[20]

In the fall of 1952, Lodge found himself fighting in a tight race for re-election with John F. Kennedy, then a US Representative. His efforts in helping Eisenhower caused Lodge to neglect his own campaign. In addition, some of Taft's supporters in Massachusetts defected from Lodge to Kennedy campaign out of anger over Lodge's support of Eisenhower.[21] In November 1952 Lodge was defeated by Kennedy; Lodge received 48.5% of the vote to Kennedy's 51.5%. It was neither the first nor the last time a Lodge faced a Kennedy in a Massachusetts election: in 1916 Henry Cabot Lodge had defeated Kennedy's grandfather John F. Fitzgerald for the same Senate seat, and Lodge's son, George, was defeated in his bid for the seat by Kennedy's brother Ted in the 1962 election for John F. Kennedy's unexpired term.

Ambassador to United Nations

Lodge was named U.S. ambassador to the United Nations by President Eisenhower in February 1953, with his office elevated to Cabinet-level rank. In contrast to his grandfather (who had been a principal opponent of the UN's predecessor, the League of Nations), Lodge was supportive of the UN as an institution for promoting peace. As he famously said about it, "This organization is created to prevent you from going to hell. It isn't created to take you to heaven."[22] Since then, no one has even approached his record of seven and a half years as ambassador to the UN. During his time as UN Ambassador, Lodge supported the Cold War policies of the Eisenhower Administration, and often engaged in debates with the UN representatives of the Soviet Union.

During the CIA-sponsored overthrowing of the legitimate Guatemalan government, when Britain and France became concerned about the US being involved in the aggression, Lodge (as US Ambassador to the United Nations) threatened to withdraw US support to Britain on Egypt and Cyprus, and to France on Tunisia and Morocco, unless they backed the US in their action.[23] When the government was overthrown, The United Fruit Company re-established itself in Guatemala. The episodes tainted an otherwise distinguished career and painted Lodge as a face of US imperialism and exceptionalism.[24]

In 1959, he escorted Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev on a highly publicized tour of the United States.

1960 Vice Presidential campaign

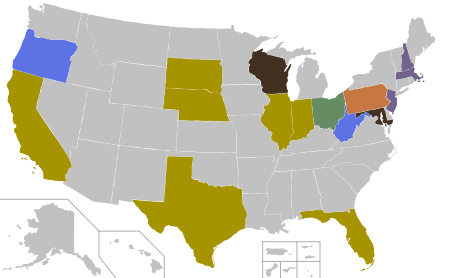

Lodge left the UN ambassadorship turning over his seat to Deputy Chief Jerry Wadsworth during the election of 1960 to run for Vice President on the Republican ticket headed by Richard Nixon, against Lodge's old foe, John F. Kennedy. Before choosing Lodge, Nixon had also considered Philip Willkie of Indiana, son of Wendell L. Willkie; U.S. Representative Gerald Ford of Michigan; and U.S. Senator Thruston B. Morton of Kentucky. Nixon finally settled on Lodge in the mistaken hope that Lodge's presence on the ticket would force Kennedy to divert time and resources to securing his Massachusetts base, but Kennedy won his home state handily. Nixon also felt that the name Lodge had made for himself in the United Nations as a foreign policy expert would prove useful against the relatively inexperienced Kennedy. Nixon and Lodge lost the election in a razor-thin vote.

The choice of Lodge proved to be questionable. He did not carry his home state for Nixon. Also, some conservative Republicans charged that Lodge had cost the ticket votes, particularly in the South, by his pledge (made without Nixon's approval) that if elected, Nixon would name at least one African American to a Cabinet post. He suggested Ralph Bunche as a "wonderful idea".[25]

Between 1961 and 1962, Lodge was the first director-general of the Atlantic Institute.[26]

Ambassador to South Vietnam

Kennedy appointed Lodge to the position of Ambassador to South Vietnam, which he held from 1963 to 1964. The new ambassador quickly determined that Ngo Dinh Diem, President of the Republic of Vietnam, was both inept and corrupt and that South Vietnam was headed for disaster unless Diem reformed his administration or was replaced.[27] While Diem was eventually assassinated and his government toppled in a November 1963 coup d'état, the coup sparked a rapid succession of leaders in South Vietnam, each unable to rally and unify their people and in turn overthrown by someone new. These frequent changes in leadership caused political instability in the South, since no strong, centralized and permanent government was in place to govern the nation, while the Viet Minh stepped up their infiltration of the Southern populace and their pace of attacks in the South. Having supported the coup against President Diem, Lodge then realized it had caused the situation in the region to deteriorate, and he suggested to the State Department that South Vietnam should be made to relinquish its independence and become a protectorate of the United States (like the former status of the Philippines) so as to bring governmental stability. The alternatives, he warned, were either increased military involvement by the U.S. or total abandonment of South Vietnam by America.[28]

"Walking for President"

|

No primary held

Henry Cabot Lodge Jr.

|

In 1964, Lodge, while still Ambassador to South Vietnam, was the surprise write-in victor in the Republican New Hampshire primary, defeating declared presidential candidates Barry Goldwater and Nelson Rockefeller.[29] His entire campaign was organized by a small band of political amateurs working independently of the ambassador, who, believing they had little hope of winning him any delegates, did nothing to aid their efforts. However, when they scored the New Hampshire upset, Lodge, along with the press and Republican party leaders, suddenly began to seriously consider his candidacy. Many observers remarked on the situation's similarity to 1952, when Eisenhower had unexpectedly defeated Senator Robert A. Taft, then leader of the Republican Party's conservative faction. However, Lodge (who refused to become an open candidate) did not fare as well in later primaries, and Goldwater ultimately won the presidential nomination.

Later career

He was re-appointed ambassador to South Vietnam by President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1965, and served thereafter as Ambassador at Large (1967–1968) and Ambassador to West Germany (1968–1969). In 1969, when his former running mate Richard M. Nixon finally became President, he was appointed by President Nixon to serve as head of the American delegation at the Paris peace negotiations, and he served occasionally as personal representative of the President to the Holy See from 1970 to 1977.[30]

Personal life

In 1926, Lodge married Emily Esther Sears. They had two children: George Cabot Lodge II (b. 1927) and Henry Sears Lodge (1930-2017).[31] George was in the federal civil service and is now a well-published professor emeritus at Harvard Business School. Henry married Elenita Ziegler of New York City and was a former sales executive.[32]

In 1966 he was elected an honorary member of the Massachusetts Society of the Cincinnati.[33]

Lodge died in 1985 after a long illness and was interred in the Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts.[34] Two years after Lodge's death, Sears married Forrester A. Clark. She died in 1992 of lung cancer and is interred near her first husband in the Cabot Lodge family columbarium.[35]

See also

References

- ↑ The Kennedys: End of a Dynasty. Life. 2009.

- ↑

- ↑ "LODGE, John Davis, (1903–1985)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved July 29, 2011.

- ↑ "Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr. Photographs II". The Massachusetts Historical Society. MHS. Retrieved 24 December 2011.

- ↑ Gale, Mary Ellen (1960-11-04). "Lodge at Harvard: Loyal Conservation 'Who Knew Just What He Wanted to Do'". The Harvard Crimson. Retrieved 2007-10-30.

- ↑ "LODGE, Henry Cabot, Jr.,(1902 - 1985)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved January 15, 2016.

- 1 2 "For Services Rendered," Time Magazine, 1942-07-20.

- ↑ "Into the Funnel," Time Magazine, 1942-07-42.

- ↑ "Lodge in the Field," Time Magazine, 1944-02-14.

- ↑ http://bioguide.congress.gov/scripts/biodisplay.pl?index=l000394

- ↑ "People," Time Magazine, 1944-10-09.

- ↑ "Reservations," Time Magazine, 1945-03-19.

- ↑ The United States and the United Nations: Hearings Before the Committee on Foreign Relations: Biography, Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. United States Senate. 1975. p. 6.

- ↑ Army, Navy, Air Force Journal. 97. Washington, DC: Army and Navy Journal Incorporated. 1960. p. 785.

- ↑ "Obituary: Henry Cabot Lodge". ARMY Magazine. Washington, DC: Association of the United States Army. 35: 15. 1985.

- ↑ Tydings hearing p.11

- ↑ Congressional Record, July 24, 1950, 10813-14

- ↑ Congressional Record, July 24, 1950, pp 10815-19

- ↑ Tydings report, p. 167

- ↑ Evans, M.Stanton (2007). Blacklisted by History. USA: Crown Forum. p. 444. ISBN 978-1-4000-8105-9.

- ↑ Whalen, Thomas J. (2000). Kennedy versus Lodge: The 1952 Massachusetts Senate Race. Boston, Mass.: Northeastern University Press. ISBN 978-1-55553-462-2.

- ↑ Bartleby, Simpson's Contemporary Quotations, compiled by James B. Simpson, 1988, news summaries January 28, 1954

- ↑ Young, John W. (1986). "Great Britain's Latin American Dilemma: The Foreign Office and the Overthrow of ‘Communist’ Guatemala, June 1954". International History Review. 8 (4): 573–592 [p. 584]. doi:10.1080/07075332.1986.9640425.

- ↑ Schlesinger, Stephen; Kinzer, Stephen. Bitter Fruit: The Untold Story of the American Coup in Guatemala. Doubleday & Company, Inc. ISBN 0385183542.

- ↑ The New York Times, October 14, 1960

- ↑ Melvin Small (1998-06-01). "The Atlantic Council—The Early Years" (PDF). NATO.

- ↑ Lodge, Henry Cabot (1979). Interview with Henry Cabot Lodge (Video interview (part 1 of 5)). Open Vault, WGBH Media Library and Archives.

- ↑ Moyar (2006). Triumph Forsaken: The Vietnam War, 1954–1965. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 273. ISBN 0-521-86911-0.

- ↑ Union-Leader: Lodge's write-in victory Archived August 2, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Petillo, Carol Morris. "Lodge, Henry Cabot". American National Biography Online.

- ↑ MHS Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr. Photographs II

- ↑ "Milestones, Aug. 8, 1960". Time. August 8, 1960.

- ↑ Roster of the Society of the Cincinnati. 1974 edition. pg. 17.

- ↑ Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr at Find a Grave

- ↑ "Emily Lodge Clark, 86; Was Senator's Widow". The New York Times. June 10, 1992.

External links

- United States Congress. "Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. (id: L000394)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- The Papers of Henry Cabot Lodge, Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library

- The short film U.S. Warns Russia to Keep Hands off in Guatemala Crisis (1955) is available for free download at the Internet Archive

- The short film STAFF FILM REPORT 66-27A (1966) is available for free download at the Internet Archive

- A film clip "Longines Chronoscope with Sen. Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr. (May 2, 1952)" is available at the Internet Archive