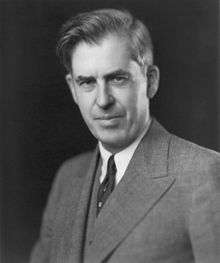

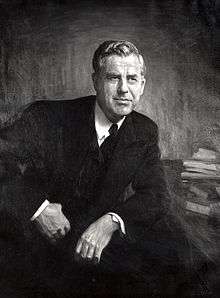

Henry A. Wallace

| Henry A. Wallace | |

|---|---|

| |

| 33rd Vice President of the United States | |

|

In office January 20, 1941 – January 20, 1945 | |

| President | Franklin D. Roosevelt |

| Preceded by | John Nance Garner |

| Succeeded by | Harry S. Truman |

| 10th United States Secretary of Commerce | |

|

In office March 2, 1945 – September 20, 1946 | |

| President |

Franklin D. Roosevelt Harry S. Truman |

| Preceded by | Jesse Holman Jones |

| Succeeded by | W. Averell Harriman |

| 11th United States Secretary of Agriculture | |

|

In office March 4, 1933 – September 4, 1940 | |

| President | Franklin D. Roosevelt |

| Preceded by | Arthur M. Hyde |

| Succeeded by | Claude R. Wickard |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Henry Agard Wallace October 7, 1888 Orient, Iowa, U.S. |

| Died |

November 18, 1965 (aged 77) Danbury, Connecticut, U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Political party |

|

| Spouse(s) | Ilo Browne (1914–1965) |

| Children |

|

| Alma mater | Iowa State University |

| Signature |

|

Henry Agard Wallace (October 7, 1888 – November 18, 1965) was the 33rd Vice President of the United States (1941–1945), the Secretary of Agriculture (1933–1940), and the Secretary of Commerce (1945–1946). Wallace was a strong supporter of New Deal liberalism, and softer policies towards the Soviet Union. His public feuds with other officials and unpopularity with party bosses in major cities caused significant controversy during his time as Vice President under Franklin D. Roosevelt in the midst of World War II, and resulted in Democrats dropping him from the ticket in the 1944 election in favor of Senator Harry S. Truman. In the 1948 presidential election, Wallace left the Democratic Party to run unsuccessfully as the nominee of the Progressive Party against Truman, Republican Thomas E. Dewey, and States' Rights Democrat Strom Thurmond. He won 2.4% of the popular vote and no electoral votes, and finished fourth.[1]

Early life

The Wallace family was of Scots-Irish Presbyterian heritage and had originally emigrated from Ulster to Pennsylvania. Henry Agard Wallace's grandfather, Henry Wallace or "Uncle Henry", was a former Presbyterian minister who preached the social gospel. As a large landowner in Iowa, Uncle Henry was an advocate of scientific farming and helped organize The Farmers' Protective Association, the Agricultural Editors Association, and the Iowa Improved Stock Association, becoming the editor of the Iowa Homestead, the state's largest and most important farm publication. He viewed it as his life mission to serve God by helping his fellow farmers.[2]

Uncle Henry's son, and Henry A. Wallace's father, was Henry Cantwell Wallace, a farmer, newspaper editor, university professor and author who would serve as the Secretary of Agriculture in the Republican administrations of Warren G. Harding and Calvin Coolidge. Henry Agard was born on October 7, 1888, at a farm near the village of Orient, Iowa, in Adair County,[3] but the family later moved to Des Moines. Wallace's mother, née May Brodhead, was deeply religious. She had been to college and was trained in music and art.[4]

Advances in agronomy

May Wallace shared her love of plants with her son while he was still a boy, teaching him to cross-breed pansies.[5] When the African-American "plant doctor" and future agronomist George Washington Carver became a student and later an instructor at Iowa State University, the Wallaces took him into their home, as racial prejudice prevented Carver from living in the dormitories. As a boy, Wallace accompanied Carver on nature walks, identifying the botanical structures of wild flowers and prairie grasses. Carver left for Tuskegee when Wallace was eight, but his influence on Wallace was deep and lasting. By the age of ten, Wallace was experimenting with plant breeding in his own plot. He also developed a keen interest in math and statistics. At fifteen, he conducted experiments to demonstrate that the then-conventional method of judging the quality of corn strains solely by such esthetic qualities as the beauty and symmetry of the ears was deeply flawed, failing to take into account the vigor and productivity of the whole plant as measured quantitatively.[6] Wallace's experiments proved that there was no relationship between yield and appearance.[7] Where plant hybridity had traditionally been viewed negatively as "mongrelization" signaling decline, Wallace's work introduced the concept of hybrid vigor.

Wallace attended Iowa State College in Ames, Iowa, graduating in 1910 with a bachelor's degree in animal husbandry. During his time at Iowa State, Wallace was a member of the Delta Tau Delta fraternity. He worked on the editorial staff of the family-owned paper Wallaces' Farmer in Des Moines from 1910 to 1924, and took the role of chief editor from 1924 to 1929. Wallace experimented with breeding high-yielding hybrid corn, and wrote a number of publications on agriculture. In 1915, he devised the first corn-hog ratio charts indicating the probable course of markets. Wallace was also a practicing statistician,[8] writing an influential article with pioneering statistician George W. Snedecor of Iowa State University on computational methods for correlations and regressions[9] and publishing sophisticated statistical studies in the pages of Wallaces’ Farmer. Snedecor invited Wallace to teach a graduate course on least squares.[10] It was Wallace, more than any other individual, who introduced econometrics (a form of statistical analysis used by economists) to the field of agriculture.[11]

In 1914, Wallace married Ilo Browne, and in 1926, with the help of a small inheritance that had been left to her, he founded the Hi-Bred Corn Company, which made him a wealthy man. The company later became Pioneer Hi-Bred, a major agriculture corporation. It was acquired in 1999 by the DuPont Corporation for approximately $10 billion.[7]

Religious explorations

Wallace was raised as a Presbyterian. In college, however, he became increasingly dissatisfied with organized religion after reading William James' The Varieties of Religious Experience (1902). Around 1919 he stopped attending the Presbyterian church[12] and spent the next ten years exploring other religious faiths and traditions, including spiritualism and esoteric religion. He later said, "I know I am often called a mystic, and in the years following my leaving the United Presbyterian Church I was probably a practical mystic ... I'd say I was a mystic in the sense that George Washington Carver was – who believed God was in everything and therefore, if you went to God, you could find the answers."[13] Wallace joined the Theosophical Society on June 6, 1925,[14] and that same year helped organize a Des Moines parish of the Liberal Catholic Church, denomination with ties to theosophy, but which had no ties to the Roman Catholic Church. He resigned from the Theosophical Society on or before November 23, 1935, and in 1939 formally joined the Episcopal Church.

One of the people with whom Wallace corresponded was the Irish poet, artist, and theosophist George William Russell, also known as Æ, who was editor of the Irish Homestead, the weekly publication of the Irish Agricultural Organisation Society (IAOS). Russell, like Wallace, was fervently dedicated to revitalizing rural life and had pioneered the rural cooperative credit union movement in Ireland.

During the 1930s Wallace also engaged in an exchange of notes with Russian émigré, artist, mystic, and peace activist Nicholas Roerich, his wife Helena Ivanova, and some of their associates at the Roerich Museum in New York. Both Nicholas and, especially, Helena, had developed their own brand of theosophy that they called Living Ethics or Agni Yoga, which emphasized a common thread running through all religions. Nicholas Roerich had been nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize and invited to Herbert Hoover's White House. Wallace had met Roerich in 1929, and Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt were also acquainted with him.[15]

Roerich, who styled himself a guru (or teacher), designed the sets and co-wrote the scenario for Igor Stravinsky's 1913 avant garde ballet The Rite of Spring.[16] During the 1920s, Roerich traveled to Tibet, considered by theosophists a repository of ancient wisdom, and in 1930 he published a book, Shambhala: In Search of the New Era, a collection of traditional legends of Tibetan Buddhism: (1930).[17] Roerich later gained international celebrity through his lobbying for the protection of the world's cultural, scientific, and artistic monuments from the ravages of war, a cause Wallace, along with such luminaries as Albert Einstein, George Bernard Shaw, and H.G. Wells adopted. Both Wallace and Roosevelt successfully lobbied Congress to support Roerich's Banner and Pact of Peace campaign, and in 1935 delegates from 22 Latin American countries met in Washington, D.C., to sign the pact. Roosevelt, who perhaps came by an interest in Asian religions through his mother Sara, also exchanged letters with Helena [Ivanova] Roerich.[15]

Years later, when he ran for president in 1948, Wallace's correspondence with Roerich and his circle, dubbed derisively "the Guru letters", would be used by his opponents as evidence of his gullibility.

Roosevelt also introduced Wallace to The Glory Road (1935), a novel by popular Broadway playwright Arthur Hopkins. Not a religious book, The Glory Road was a historical-political allegory inspired by the economic devastation wrought by the Great Depression. On its dust jacket The Glory Road is said to describe "the experience of the human race as it has tried to follow the road of truth while at the same time building up for itself a structure of civilization that will yield material wealth".[18] Culver and Hyde identify this book as the source of the pen-names Wallace later adopted in some of his correspondence – perhaps including the so-called "Guru letters". For example, in a letter to FDR, Wallace says, "You can be 'the flaming one'." Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. describes Wallace's references to figures in The Glory Road (such as "the fervent one" and so on), as "rash" and "cabalistic", bespeaking what Schlesinger calls "moods of rapture."[19] However, Wallace's use of the term in addressing Roosevelt is likely an in-joke, since in The Glory Road there is no "flaming one", but rather a "flameless one', "elected as his people's executive", supported by bankers and corrupt leaders, who urges the electorate to "buy, buy, buy" as a way out of economic collapse.[20]

Political career

Secretary of Agriculture

In 1933, President Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed Wallace United States Secretary of Agriculture in his Cabinet, a post Wallace's father, Henry Cantwell Wallace, had occupied from 1921 to 1924. Henry A. Wallace was a registered Republican and would remain so until 1936,[21] but he belonged to the progressive wing of the party and had campaigned for Democratic candidate Al Smith. Wallace was one of three Republicans whom Roosevelt appointed to his cabinet (the others were Harold Ickes, Secretary of the Interior, and William H. Woodin, Secretary of the Treasury). As Agriculture Secretary, Wallace's policies were controversial: to raise prices of agricultural commodities he instituted the slaughtering of hogs, plowing up cotton fields, and paying farmers to leave some lands fallow. He also advocated the ever-normal granary concept. Wallace, by his own account, learned about this institution by reading a Columbia University doctoral dissertation by an ardent Confucian propagandist, Chen Huan-chang. [22] Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., critical of Wallace in many respects, pronounced Wallace "the best secretary of agriculture the country has ever had", writing:

In 1933, a quarter of the American people still lived on farms, and agricultural policy was a matter of high political and economic significance. Farmers had been devastated by depression. H.A.'s ambition was to restore the farmers' position in the national economy. He sought to give them the same opportunity to improve income by controlling output that business corporations already possessed. In time he widened his concern beyond commercial farming to subsistence farming and rural poverty. For the urban poor, he provided food stamps and school lunches. He instituted programs for land-use planning, soil conservation, and erosion control. And always he promoted research to combat plant and animal diseases, to locate drought-resistant crops and to develop hybrid seeds in order to increase productivity.[23]

Roerich controversy

In 1933, the Roosevelt Administration, which had just formally recognized the Soviet Union, sent Nicholas Roerich and his Harvard-educated son George, who had studied Asian languages and later became a noted scholar of Tibet, on a horticultural expedition to Central Asia on behalf of Wallace's Department of Agriculture. Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., who was hostile to Wallace, writes that "Wallace did Roerich a number of favors, including sending him on an expedition to Central Asia presumably to collect drought-resistant grasses. In due course, H.A. [Wallace] became disillusioned with Roerich and turned almost viciously against him."[24] Wallace biographers John C. Culver and John Hyde, however, write that it is unclear with whom the idea for the Roerich expedition originated, since in cabinet meetings Wallace had opposed Roosevelt's granting of recognition to the Soviet government because of its hostility to organized religion and his fear it would dump grain on the United States.[15] However, once in Asia, Roerich upset the diplomatic world and the US agricultural experts who accompanied him by neglecting botany and, instead, searching for and possibly trying to bring about a revival of the legendary Shambhalla, variously located in Tibet, Bhutan, Nepal, or Manchuria. These areas were partly under the jurisdiction of the British and Japanese empires, which did not look kindly on movements for national self-determination and believed Roerich to be a Russian spy and/or anti-Imperialist agitator. After Wallace recalled him, the U.S. government aggressively pursued Roerich for tax evasion, and the artist (the holder of a French passport) took up residence in India, where gurus were not considered so unusual.

The Republicans threatened to reveal to the public what they characterized as Wallace's bizarre religious beliefs prior to the November 1940 elections but were deterred when the Democrats countered by threatening to release information about Republican candidate Wendell Willkie's rumored extramarital affair with the writer Irita Van Doren.[24][25] The contents of the letters did become public seven years later, in the winter of 1947, when right-wing columnist Westbrook Pegler published what were purported to be extracts from them as evidence that Wallace was a "messianic fumbler," and "off-center mentally". During the 1948 campaign Pegler and other hostile reporters, including H.L. Mencken, aggressively confronted Wallace on the subject at a public meeting in Philadelphia in July. Wallace declined to comment, accusing the reporters of being Pegler's stooges.[26]

Vice President

Wallace served as Secretary of Agriculture until September 1940, after Franklin Roosevelt selected him as his running mate on the 1940 presidential ticket. Among party regulars the choice was controversial. The conservative wing of the Democratic Party, many of them Southerners, distrusted Wallace:

Wallace was an unreconstructed liberal reformer and New Dealer, qualities that recommended him to Roosevelt. The old guard Democratic Party bosses deeply distrusted Wallace as an apostate Republican and as a doe-eyed mystic who symbolized all that they found objectionable about [what they saw as] the hopelessly utopian, market-manipulating, bureaucracy-breeding New Deal.[27]

Boos echoed through the convention hall when Roosevelt's choice of Wallace was announced, and the delegates seemed on the verge of rebellion. It was only after Roosevelt threatened to decline the nomination and Eleanor Roosevelt delivered a conciliatory speech that they grudgingly yielded.[28] Wallace received the support of 626.3 votes (around 59% of the 1100 delegates) when nominated at the convention, compared to 329.6 votes for Speaker of the House William B. Bankhead of Alabama (who incidentally died only months after the 1940 Democratic National Convention).

The ticket found favor with the electorate, however. In November 1940, Roosevelt was handily re-elected for a third term – the Electoral College vote was 449 to 82.

As of 2017, he remains the last Democratic vice president who never served in the United States Senate and indeed the last vice president of any party who had not previously held any elected office.

Roosevelt named Wallace chairman of the Board of Economic Warfare (BEW) and of the Supply Priorities and Allocation Board (SPAB) in 1941. Both positions became important with the U.S. entry into World War II.[29] As he began to flex his newfound political muscle in his position with SPAB, Wallace came up against the conservative wing of the Democratic Party in the form of Jesse H. Jones, Secretary of Commerce, as the two differed on how to handle wartime supplies.

On May 8, 1942, Wallace delivered what became his most famous speech, to the Free World Association in New York City. The speech, delivered during the darkest days of the war, was formally titled "The Price of Free World Victory" but came to be identified by its phrase "the century of the common man". This was Wallace's answer to Republican publisher Henry Luce's call for an "American Century" after the war. For Wallace the war was a conflict between the slave states and the free world.

"The concept of freedom," Wallace explained, was rooted in the Bible, with its "extraordinary emphasis on the dignity of the individual," but only recently had it become a reality for large numbers of people. "Democracy is the only true political expression of Christianity," he declared, adding that with freedom must come abundance. "Men and women can never be really free until they have plenty to eat, and time and ability to read and think and talk things over."[30]

For Wallace the outcome of the war had to be more than a restoration of the status quo. He wished to see the ideals of New Deal liberalism continuing at home and spreading throughout a world in which colonialism had been abolished and where labor would be represented by unions. "Most of all," write Culver and Hyde, "He wanted to end the deadly cycle of economic warfare followed by military combat followed by isolationism and more economic warfare and more conflict.”[31] For millions Wallace's speech defined America's mission in the war and the vision of a peaceful and more equitable world to follow.[32] Nevertheless, it roused the ire of more conservative Democrats, business leaders and conservatives, not to mention Winston Churchill, who was strongly committed to preserving Britain's colonial empire.

Wallace also famously spoke out during the Detroit race riot of 1943, declaring that the nation could not "fight to crush Nazi brutality abroad and condone race riots at home."

In 1943, Wallace made a goodwill tour of Latin America, shoring up support among important allies. His trip proved a success, and helped persuade twelve countries to declare war on Germany. Regarding trade relationships with Latin America, he convinced the BEW to add labor clauses to contracts with Latin American producers. These clauses required producers to pay fair wages and provide safe working conditions for their employees, and committed the United States to paying for up to half of the required improvements. This met opposition from the Department of Commerce.

After meeting Vyacheslav Molotov, Wallace arranged a trip to the "Wild East" of Soviet Union. On May 23, 1944, he started a 25-day journey accompanied by Owen Lattimore. Coming from Alaska, they landed at Magadan, where they were received by Sergo Goglidze and Dalstroi director Ivan Nikishov, both NKVD generals. The NKVD presented a fully sanitized version of the labor camps in Magadan and Kolyma to their American guests, claiming that all the work was done by volunteers. The delegation was provided with entertainment, and by some accounts left impressed with the "development" of Siberia and the spirit of the "volunteers". Lattimore's film of the visit tells that "a village... in Siberia is a forum for open discussion like a town meeting in New England."[33] This visit took place while the United States and the Soviet Union were allies; American propaganda regularly portrayed the Soviet Union in a positive light. The trip continued through Mongolia and then to China.

After Wallace feuded publicly with Secretary of Commerce Jesse H. Jones and other high officials, Roosevelt stripped him of his war agency responsibilities. Although a Gallup poll taken just before the 1944 Democratic National Convention found 65% of those surveyed favored renomination for Wallace and only 2% favored his eventual opponent, Harry S. Truman, it was Truman who went on to win the vice presidential nomination.[34] During the 1944 Democratic convention Wallace had a favorable lead on the other candidates for the vice presidential nomination, but lacked the majority needed to win the nomination. In a turn of events much scrutinized, just as Wallace began to receive the votes needed for the nomination, the convention was deemed a fire hazard and pushed back to the next day. When the convention resumed Truman made a jump from 2% in the polls all the way to winning the nomination. Wallace was succeeded as Vice President on January 20, 1945, and on April 12, Vice President Truman succeeded to the Presidency when President Franklin D. Roosevelt died.

Secretary of Commerce

Appointment and confirmation

Roosevelt appointed Wallace to be Secretary of Commerce in January 1945, shortly before Roosevelt's death, as a sort of consolation prize for losing the vice presidency.[35] Wallace's nomination prompted an intense debate. During his confirmation hearings before the Senate Judiciary Committee in early January 1945, Wallace "called to a guaranteed annual minimum wage for all employees, maintenance of high wartime wages in the postwar era, and automatic government pump-priming to be triggered whenever the number of jobs in the nation fell below 57 million. For both supporters and opponents, therefore, Wallace's nomination was a symbol of the Administration's intent to resume New Deal reform, with its emphasis on Executive leadership, at war's end."[36] Senate conservatives tried to stymie Wallace's prospective future powers through a measure, proposed by Walter F. George, to remove the Federal Loan Administration—and therefore the Reconstruction Finance Corporation and its $32 billion in lending authority—from the Commerce Department. This measure was adopted. Some conservatives, such as Harry F. Byrd and Josiah Bailey, sought to defeat Wallace's nomination altogether; Bailey made a motion on February 1 to immediately proceed to the nomination, "in the belief that if the powers of the Commerce Department were not diminished, Henry Wallace would never win confirmation."[37] The motion was defeated on a 42-42 vote, however, and the George bill was approved before the Wallace nomination came to the floor.[38]

On March 1, 1945, Wallace was confirmed by a vote of 56-31.[39][40] Five Democrats, four of whom were Southern Democrats, voted against Wallace's confirmation.[41]

Tenure

The outspoken Wallace continued to be controversial, exasperating conservatives and moderates, and even, at times, his allies. His conservative opponents were infuriated when Wallace objected that a militaristic stance toward the Soviet Union was likely to be counterproductive, while his left-leaning audiences booed when he criticized the Soviets.[42] With the development of the atomic bomb, Wallace wrote that "as long as the United States makes atomic bombs she will be looked upon as the world's outstanding aggressor nation." He also wanted the American nuclear program under the control of civilian agencies, completely out of the hands of the military.[43] In a speech delivered on April 12, 1946, Wallace distanced himself from the United States' former wartime allies, stating that "aside from our common language and common literary tradition, we have no more in common with Imperialistic England than with Communist Russia". Historian Tony Judt (who calls Wallace "notoriously 'soft' on Communism"), notes that at the time such "distaste for American involvement with Britain and Europe was widely shared across the political spectrum." Most Americans, he writes, wanted neither European alliances nor expected American troops to be stationed overseas. For a time, Truman himself appeared undecided.[44] By September 1946, however, Truman had fired Wallace, the last of FDR's appointees still in office, having dismissed all of the others in the first 12 months of his presidency.[45] Wallace is the last former vice president to serve in a president's cabinet.

The New Republic

Following his term as Secretary of Commerce, Wallace became the editor of The New Republic magazine, which he used as a platform to oppose Truman's foreign policies. On the declaration of the Truman Doctrine in 1947, he predicted it would mark the beginning of "a century of fear".

1948 presidential election

Wallace left his editorship position in 1948 to make an unsuccessful run as the Progressive Party's presidential candidate in the 1948 U.S. presidential election. With Idaho Democratic Senator Glen H. Taylor as his vice presidential running mate, his platform advocated universal government health insurance, an end to the nascent Cold War, full voting rights for black Americans, and an end to segregation. His campaign included African American candidates campaigning alongside white candidates in the segregated South and he also refused to appear before segregated audiences or to eat or stay in segregated establishments.

Time magazine, which opposed the Wallace candidacy, described Wallace as "ostentatiously" riding through the towns and cities of the segregated South "with his Negro secretary beside him".[46] A barrage of eggs and tomatoes were hurled at Wallace and struck him and his campaign members during the tour. Wallace's opponent President Truman, condemned such mob violence as "highly un-American business which violated the American concept of fair play." State authorities in Virginia sidestepped enforcing their own segregation laws by declaring Wallace's campaign gatherings as private parties.[47]

The "Guru letters" reappeared and were published, seriously damaging his campaign.[24] More damage was done to Wallace's campaign when journalists H.L. Mencken and Dorothy Thompson, both longtime and vocal New Deal opponents,[48] charged that Wallace and the Progressives were under the covert control of Communists.

Wallace's refusal to disavow publicly his endorsement by the Communist Party cost him the backing of many anti-Communist liberals and of independent socialist Norman Thomas. Wallace suffered a decisive defeat in the election to the Democratic incumbent Harry S. Truman. He finished in fourth place with 2.4% of the popular vote. Some historians now believe his candidacy was a blessing in disguise for Truman, as Wallace's frequent criticisms of Truman's foreign policy, combined with his overt acceptance of Communist support, served as a refutation of the Republicans' claim that Truman was "soft on communism". Dixiecrat presidential candidate Strom Thurmond finished ahead of Wallace in the popular vote. Thurmond managed to carry four states in the Deep South (all in which he was designated as the "Democratic" nominee), gaining 39 electoral votes to Wallace's electoral total of zero.

Later career and death

Wallace then resumed his farming interests and resided in South Salem, New York. During his later years he made a number of advances in the field of agricultural science. His many accomplishments included a breed of chicken that at one point accounted for the overwhelming majority of all egg-laying chickens sold across the globe. The Henry A. Wallace Beltsville Agricultural Research Center, the largest agricultural research complex in the world, is named for him.

In 1950 during the McCarthy era, when North Korea invaded South Korea, Wallace broke with the Progressives and backed the U.S.-led effort in the Korean War.[24] Despite this, according to Wallace's diary, after his 1951 Senate Internal Security Subcommittee testimony, opinion polls showed that he was only beaten by gangster Lucky Luciano as the "least approved man in America". Previously, after hearing from Gulag survivor and friend Vladimir Petrov about the true nature of the 1944 Vice Presidential visit to Magadan, Wallace had publicly apologized for having allowed himself to be fooled by the Soviets.[49] In 1952 Wallace published Where I Was Wrong, in which he explained that his seemingly-trusting stance toward the Soviet Union and Joseph Stalin stemmed from inadequate information about Stalin's crimes, and that he now considered himself an anti-Communist.

He wrote various letters to "people who he thought had traduced [maligned] him" and advocated the re-election of President Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1956.[24] In 1961, President-elect John F. Kennedy invited Wallace to his inauguration ceremony, even though he had supported Kennedy's opponent Richard Nixon. (Like Wallace, Nixon had been Vice President before becoming a presidential candidate). A touched Wallace wrote to Kennedy: "At no time in our history have so many tens of millions of people been so completely enthusiastic about an Inaugural Address as about yours."[24]

Wallace first experienced the onsets of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in 1964.[50] He died in Danbury, Connecticut, on November 18, 1965.[24][51] His remains were cremated and the ashes interred in Glendale Cemetery in Des Moines, Iowa.

See also

- Honeydew (melon), apparently first introduced to China by H.A. Wallace and still known there as the "Wallace melon"[52][53]

- Bailan melon, one of the most famous Chinese melon cultivars, bred from the "Wallace melon"

Bibliography

- Agricultural Prices (1920)

- New Frontiers (1934)

- America Must Choose (1934)

- Statesmanship and Religion (1934)

- Technology, Corporations, and the General Welfare (1937)

- The Century of the Common Man (1943)

- Democracy Reborn (1944)

- Sixty Million Jobs (1945)

- Soviet Asia Mission (1946)

- Toward World Peace (1948)

- Where I Was Wrong (1952)

- The Price of Vision – The Diary of Henry A. Wallace 1942–1946 (1973), edited by John Morton Blum

References

- ↑ "1948 Presidential General Election Results". Retrieved July 5, 2017.

- ↑ John C. Culver and John Hyde, American Dreamer: The Life and Times of Henry A. Wallace (W.W. Norton, 2001), p. 8.

- ↑ "Papers of Henry A. Wallace". University of Iowa. Retrieved 2009-04-28.

- ↑ Culver and Hyde, American Dreamer, p. 9.

- ↑ Culver and Hyde, American Dreamer, p. 2.

- ↑ Culver and Hyde, American Dreamer, pp. 27–28.

- 1 2 "1926 Henry A. Wallace". DuPont. Retrieved 2014-06-23.

- ↑ Farebrother, Richard William (2008). "Henry Agard Wallace and Machine Calculation" (PDF). The Bulletin of the International Linear Algebra Society (40): 1–24

- ↑ Wallace, Henry Agard; Snedecor, George Waddel (1925). "Correlation and Machine Calculation". Iowa State College Bulletin. 35

- ↑ Grier, David Alan. "The Origins of Statistical Computing". Statisticians in History. American Statistical Association. Retrieved 2012-03-01.

- ↑ See "The Life of Henry A. Wallace, 1888–1965", on website of The Wallace Center for Agricultural and Environmental Policy of Winrock International.

- ↑ Culver and Hyde, American Dreamer, p. 77.

- ↑ The Reminiscences of Henry Agard Wallace, Oral history at Columbia University (1951), quoted in Culver and Hyde, American Dreamer, p. 78

- ↑ "Theosophy on War and Peace - Theosophical Society in America". theosophical.org. Retrieved 2014-10-16.

- 1 2 3 Culver and Hyde, American Dreamer, p. 136.

- ↑ Alex Ross, "Henry Wallace" in The Rest is Noise, Oct. 14, 2013. Blog post published by The New Yorker. On Roerich's posthumous artistic reputation, especially in Russia, see also Julie Besonen, "Visions of a Forgotten Utopian", New York Times, April 4, 2014.

- ↑ The legend of the enlightened land of Shambhala, that had solved the human problems of greed and violence, was the inspiration for "Shangri-la" in James Hilton's 1933 best-seller, Lost Horizon. The novel was a favorite of Roosevelt's, who named his presidential retreat Shangri-la after it. Under Republican President Dwight D. Eisenhower, the retreat was rechristened Camp David.

- ↑ Kirkus Review Summary of The Glory Road.

- ↑ Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., The Coming of the New Deal, 1933–1935: The Age of Roosevelt, Vol. 2 (New York: Mariner Books [1958, 1986], 2003) pp. 32–33.

- ↑ Arthur Hopkins, The Glory Road (New York: Dutton, 1935), p. 141.

- ↑ David M. Kennedy, Freedom from Fear: the American People in Depression and War 1929–1945 (Oxford University Press, 1999), p. 457.

- ↑ Derk Bodde, "Henry A. Wallace and the Ever-Normal Granary," The Far Eastern Quarterly 5.4 (Aug. 1946):411-426

- ↑ Arthur Schlesinger Jr., "Who Was Henry A. Wallace?", Los Angeles Times (March 20, 2000). Eric Rauchway, on the other hand, argues that the farm states then and now had and have too much influence relative to their small population, to the detriment of urban areas. He calls Wallace's policies misguided because the family farm with single-family dwelling was a nineteenth-century dream unsuited to modern needs. The future of agriculture, in his view, lay in industrial farming. Further, Rauchway characterizes as heartless such New Deal price-support measures as plowing up excess cotton and destroying excess baby pigs. Rauchway does admit, however, that 90% of farmers during the New Deal era supported Roosevelt's policies. See Eric Rauchway, The Great Depression and the New Deal: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press, 2008), Chapter 5, "Managing Farm and Factory", pp. 72–86.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Arthur Schlesinger Jr. / Who Was Henry A. Wallace?

- ↑ The religion of Henry A. Wallace, U.S. Vice-President

- ↑ Pegler's column for July 27, 1948, "In Which Our Hero Beards 'Guru' Wallace In His Own Den."

- ↑ Kennedy, Freedom from Fear, p. 457.

- ↑ David M. Kennedy believes that in nominating Wallace, Roosevelt was "throwing a bouquet" to "old progressive wing of the Republican Party, represented by George W. Norris, Hiram Johnson, and Robert La Follette Jr., in hopes that they would join the New Deal Coalition (see David Kennedy, Freedom from Fear, p. 457).

- ↑ Herman, Arthur. Freedom's Forge: How American Business Produced Victory in World War II, pp. 152-3, 155, 162-4, 196, Random House, New York, NY, 2012. ISBN 978-1-4000-6964-4.

- ↑ Culver and Hyde, American Dreamer, p. 276

- ↑ Culver and Hyde, American Dreamer, p. 271

- ↑ Culver and Hyde, American Dreamer, p. 277.

- ↑ Tim Tzouliadis. The Forsaken. The Penguin Press (2008). pp. 217–226. ISBN 978-1-59420-168-4.

- ↑ Editorial. "Yesterday's Defeat, Tomorrow's Hope" St. Petersburg Times, St. Petersburg, FL., 22 July 1944, p1 https://news.google.com/newspapers?id=vWkxAAAAIBAJ&sjid=xU4DAAAAIBAJ&pg=7238%2C354247

- ↑ Robert J. Donovan, Conflict and Crisis: The Presidency of Harry S. Truman, 1945-1948 (University of Missouri Press, 1977), p. 113.

- ↑ John William Malsberger, From Obstruction to Moderation: The Transformation of Senate Conservatism, 1938-1952 (Susquehanna University Press, 2000), p. 131.

- ↑ Malsberger, From Obstruction to Moderation, pp. 131-32.

- ↑ Malsberger, p. 132.

- ↑ John C. Culver & John Hyde, American Dreamer: The Life and Times of Henry A. Wallace (W. W. Norton & Company, 2000), p. 384.

- ↑ Leonard Dinnerstein, "The Senate's Rejection of Aubrey Williams as Rural Electrification Administration" in From Civil War to Civil Rights, Alabama 1860–1960: An Anthology from The Alabama Review (ed. Sarah Woolfolk Wiggins: University of Alabama Press, 1987), p. 439 (citing Congressional Record, 1616).

- ↑ Dinnerstein, p. 439.

- ↑ See Denise M. Bostdorf, "Henry Wallace Controversy and Firing: September 1946", pp. 31–37, in Proclaiming the Truman Doctrine: The Cold War Call to Arms (Texas A&M Press, 2008).

- ↑ Robert L. Baker (2003). "Henry Wallace Would Never Have Dropped the Bomb on Japan". Retrieved August 1, 2016.

- ↑ See Tony Judt (2005). Postwar: A History of Europe Since 1945. The Penguin Press. p. 110.

- ↑ Peter Dreier, "Henry Wallace, America's Forgotten Visionary", Truthout, February 3, 2013.

- ↑ "National Affairs – Eggs in the Dust". Time. September 13, 1948. Retrieved 2009-01-17.

- ↑ "Am I in America?". Time. September 6, 1948. Retrieved 2009-01-17.

- ↑ Mencken, an opponent of democracy, had called the New Deal "a complete repudiation of the American moral system". See Vincent Fitzpatrick, H. L. Mencken (Mercer University Press, 1989) p. 110; for Dorothy Thompson, see Carl Rollyson, "Cherchez La Femme ", The New Criterion (February 2012).

- ↑ Tzouliadis, T. (2008). The Forsaken: An American Tragedy in Stalin's Russia. Penguin Group US. ISBN 9781440637032. Retrieved 2014-10-16.

- ↑ http://www.wallace.org/henrya.html Wallace.org

- ↑ "Henry A. Wallace". The New York Times. November 19, 1965.

Although his career was marred by one major failure of judgment, Henry A. Wallace contributed significantly to the progress and prosperity of his country.

- ↑ Dirlik, Arif; Wilson, Rob (1995). Asia/Pacific as space of cultural production. Durham, N.C: Duke University Press. ISBN 0-8223-1643-9.

- ↑ A Guide to the Barbarian Vegetables of China, Lucky Peach, June 30, 2015

Further reading

- Conant, Jennet. The Irregulars: Roald Dahl and the British Spy Ring in Wartime Washington. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2008. British Intelligence surveillance of Vice President Henry A. Wallace and other Washington figures during and immediately after World War II.

- Culver, John C. and John Hyde. American Dreamer: The Life and Times of Henry A. Wallace. New York: W.W. Norton, 2002.

- Devine, Thomas W. Henry Wallace's 1948 Presidential Campaign and the Future of Postwar Liberalism. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2013.

- Macdonald, Dwight. Henry Wallace: the Man and the Myth. Vanguard Press, 1948.

- Markowitz, Norman D. The Rise and Fall of the People's Century: Henry A. Wallace and American Liberalism, 1941–1948. New York: The Free Press, 1973.

- Maze, John and Graham White, Henry A. Wallace: His Search for a New World Order. University of North Carolina Press. 1995

- Pietrusza, David 1948: Harry Truman's Improbable Victory and the Year that Changed America. Union Square Press, 2011.

- Schapsmeier, Edward L. and Frederick H. Schapsmeier. Prophet in Politics: Henry A. Wallace and the War Years, 1940–1965. Ames: Iowa State University Press, 1970.

- Schapsmeier, Edward L. and Frederick H. Schapsmeier. Henry A. Wallace of Iowa: the Agrarian Years, 1910–1940. Ames: Iowa State University Press, 1968.

- Schmidt, Karl M. Henry A. Wallace, Quixotic Crusade 1948. Syracuse University Press, 1960.

- Walker, J. Samuel Walker. Henry A. Wallace and American Foreign Policy. Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press, 1976.

- Wheatcroft, Geoffrey. "The Prince of Wallese". Times Literary Supplement, November 24, 2000.

External links

- United States Congress. "Henry A. Wallace (id: W000077)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- http://wgf.org/ The Wallace Global Fund. To promote an informed and engaged citizenry, to fight injustice, and to protect the diversity of nature and the natural systems upon which all life depends.

- Mark O. Hatfield, with the Senate Historical Office. "Henry Agard Wallace, 33rd Vice President (1941-1945)". In Senate History, Vice Presidents of the United States, 1789-1993, Introduction by Mark O. Hatfield, pp. 399-406. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1997. United States Senate Website.

- Selected Works of Henry A. Wallace

- The text of Wallace's 1942 speech "The Century of the Common Man"

- As delivered transcript and complete audio of Wallace's 1942 "The Century of the Common Man" Address

- Papers of Henry Wallace Digital Collection

- Searchable index of Wallace papers at the Library of Congress, Franklin D Roosevelt Library, and the University of Iowa

- "Henry A. Wallace – Agricultural Pioneer, Visionary and Leader", Iowa Pathways, education site of Iowa Public Television

- "The Life of Henry A. Wallace: 1888–1965", on website of The Wallace Center for Agricultural and Environmental Policy at Winrock International

- A film clip "Longines Chronoscope with Henry A. Wallace (December 28, 1951)" is available at the Internet Archive

- A film clip "Longines Chronoscope with Henry Agard Wallace (October 17, 1952)" is available at the Internet Archive

- "Is There Any 'Wallace' Left in the Democratic Party?", The Real News (TRNN). Scott Wallace, grandson of Henry A. Wallace, interviewed by Paul Jay (video).

- FBI file on Henry Wallace

- The Country Life Center location of The Wallace Centers of Iowa: birthplace farm of Henry A. Wallace. Museum and gardens.

| Preceded by Jesse Holman Jones |

U.S. Secretary of Commerce Served under: Franklin D. Roosevelt, Harry S. Truman March 2, 1945 – September 20, 1946 |

Succeeded by W. Averell Harriman |

| Preceded by John N. Garner |

Vice President of the United States January 20, 1941 – January 20, 1945 |

Succeeded by Harry S. Truman |

| Preceded by Arthur M. Hyde |

U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Served under: Franklin D. Roosevelt March 4, 1933 – September 4, 1940 |

Succeeded by Claude R. Wickard |

| Party political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Franklin D. Roosevelt |

American Labor nominee for President of the United States 1948 |

Succeeded by Vincent Hallinan |

| New political party | Progressive nominee for President of the United States 1948 | |

| Preceded by John N. Garner |

Democratic nominee for Vice President of the United States 1940 |

Succeeded by Harry S. Truman |