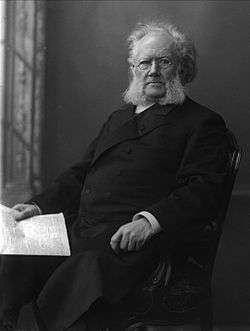

Henrik Ibsen

| Henrik Ibsen | |

|---|---|

|

Henrik Ibsen by Gustav Borgen | |

| Born |

Henrik Johan Ibsen 20 March 1828 Skien, Telemark, Norway |

| Died |

23 May 1906 (aged 78) Kristiania, Norway (modern Oslo) |

| Nationality | Norwegian |

| Occupation | Writer |

| Spouse(s) | Suzannah Thoresen (m. 1858) |

| Children | Sigurd Ibsen |

| Parent(s) |

Knud Ibsen (father) Marichen Altenburg (mother) |

| Writing career | |

| Genres |

Naturalism Realism |

| Notable works |

Peer Gynt (1867) A Doll's House (1879) Ghosts (1881) An Enemy of the People (1882) The Wild Duck (1884) Hedda Gabler (1890) |

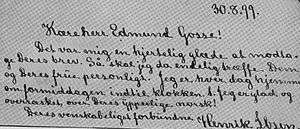

| Signature | |

|

| |

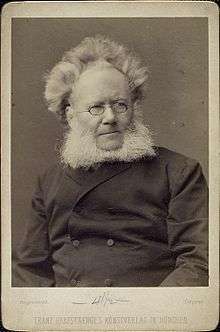

Henrik Johan Ibsen (/ˈɪbsən/;[1] Norwegian: [ˈhenrik ˈipsn̩]; 20 March 1828 – 23 May 1906) was a major 19th-century Norwegian playwright, theatre director, and poet. He is often referred to as "the father of realism" and is one of the founders of Modernism in theatre.[2] His major works include Brand, Peer Gynt, An Enemy of the People, Emperor and Galilean, A Doll's House, Hedda Gabler, Ghosts, The Wild Duck, When We Dead Awaken, Pillars of Society, The Lady from the Sea, Rosmersholm, The Master Builder, and John Gabriel Borkman. He is the most frequently performed dramatist in the world after Shakespeare,[3][4] and by the early 20th century A Doll's House became the world's most performed play.[5]

Several of his later dramas were considered scandalous to many of his era, when European theatre was expected to model strict morals of family life and propriety. Ibsen's later work examined the realities that lay behind many façades, revealing much that was disquieting to many contemporaries. It utilized a critical eye and free inquiry into the conditions of life and issues of morality. The poetic and cinematic early play Peer Gynt, however, has strong surreal elements.[6]

Ibsen is often ranked as one of the most distinguished playwrights in the European tradition.[7] Richard Hornby describes him as "a profound poetic dramatist—the best since Shakespeare".[8] He is widely regarded as the most important playwright since Shakespeare.[7][9] He influenced other playwrights and novelists such as George Bernard Shaw, Oscar Wilde, Arthur Miller, James Joyce, Eugene O'Neill, and Miroslav Krleža. Ibsen was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1902, 1903, and 1904.[10]

Ibsen wrote his plays in Danish (the common written language of Denmark and Norway)[11] and they were published by the Danish publisher Gyldendal. Although most of his plays are set in Norway—often in places reminiscent of Skien, the port town where he grew up—Ibsen lived for 27 years in Italy and Germany, and rarely visited Norway during his most productive years. Born into a merchant family connected to the patriciate of Skien, Ibsen shaped his dramas according to his family background. He was the father of Prime Minister Sigurd Ibsen. Ibsen's dramas continue in their influence upon contemporary culture and film.

Early life and family

Ibsen was born to Knud Ibsen (1797–1877) and Marichen Altenburg (1799–1869), in a well-to-do merchant family, in the small port town of Skien in Telemark county, a city which was noted for shipping timber. As he wrote in an 1882 letter to critic and scholar Georg Brandes, "my parents were members on both sides of the most respected families in Skien", explaining that he was closely related with "just about all the patrician families who then dominated the place and its surroundings", mentioning the families Paus, Plesner, von der Lippe, Cappelen and Blom.[12][13] Ibsen's grandfather, ship captain Henrich Ibsen (1765–1797), had died at sea in 1797, and Knud Ibsen was raised on the estate of ship-owner Ole Paus (1766–1855), after his mother Johanne, née Plesner (1770–1847), remarried. Knud Ibsen's half-brothers included lawyer and politician Christian Cornelius Paus, banker and ship-owner Christopher Blom Paus, and lawyer Henrik Johan Paus, who grew up with Ibsen's mother in the Altenburg home and after whom Henrik (Johan) Ibsen was named.

Knud Ibsen's paternal ancestors were ship captains of Danish origin, but he decided to become a merchant, having initial success. His marriage to Marichen Altenburg, a daughter of ship-owner Johan Andreas Altenburg (1763–1824) and Hedevig Christine Paus (1763–1848), was a successful match.[14] Theodore Jorgenson points out that "Henrik's ancestry [thus] reached back into the important Telemark family of Paus both on the father's and on the mother's side. Hedvig Paus must have been well known to the young dramatist, for she lived until 1848."[15] Henrik Ibsen was fascinated by his parents' "strange, almost incestuous marriage," and would treat the subject of incestuous relationships in several plays, notably his masterpiece Rosmersholm.[16]

When Henrik Ibsen was around seven years old, however, his father's fortunes took a significant turn for the worse, and the family was eventually forced to sell the major Altenburg building in central Skien and move permanently to their small summer house, Venstøp, outside of the city.[17] Henrik's sister Hedvig would write about their mother: "She was a quiet, lovable woman, the soul of the house, everything to her husband and children. She sacrificed herself time and time again. There was no bitterness or reproach in her."[14][18] The Ibsen family eventually moved to a city house, Snipetorp, owned by Knud Ibsen's half-brother, wealthy banker and ship-owner Christopher Blom Paus.[14]

His father's financial ruin would have a strong influence on Ibsen's later work; the characters in his plays often mirror his parents, and his themes often deal with issues of financial difficulty as well as moral conflicts stemming from dark secrets hidden from society. Ibsen would both model and name characters in his plays after his own family. A central theme in Ibsen's plays is the portrayal of suffering women, echoing his mother Marichen Altenburg; Ibsen's sympathy with women would eventually find significant expression with their portrayal in dramas such as A Doll's House and Rosmersholm.[14]

At fifteen, Ibsen was forced to leave school. He moved to the small town of Grimstad to become an apprentice pharmacist and began writing plays. In 1846, when Ibsen was age 18, a liaison with Else Sophie Jensdatter Birkedalen which produced a son, Hans Jacob Hendrichsen Birkdalen, whose upbringing Ibsen paid until the boy was fourteen, though Ibsen never saw Hans Jacob. Ibsen went to Christiania (later renamed Kristiania and then Oslo) intending to matriculate at the university. He soon rejected the idea (his earlier attempts at entering university were blocked as he did not pass all his entrance exams), preferring to commit himself to writing. His first play, the tragedy Catilina (1850), was published under the pseudonym "Brynjolf Bjarme", when he was only 22, but it was not performed. His first play to be staged, The Burial Mound (1850), received little attention. Still, Ibsen was determined to be a playwright, although the numerous plays he wrote in the following years remained unsuccessful.[19] Ibsen's main inspiration in the early period, right up to Peer Gynt, was apparently Norwegian author Henrik Wergeland and the Norwegian folk tales as collected by Peter Christen Asbjørnsen and Jørgen Moe. In Ibsen's youth, Wergeland was the most acclaimed, and by far the most read, Norwegian poet and playwright.

Life and writings

He spent the next several years employed at Det norske Theater (Bergen), where he was involved in the production of more than 145 plays as a writer, director, and producer. During this period, he published five new, though largely unremarkable, plays. Despite Ibsen's failure to achieve success as a playwright, he gained a great deal of practical experience at the Norwegian Theater, experience that was to prove valuable when he continued writing.

Ibsen returned to Christiania in 1858 to become the creative director of the Christiania Theatre. He married Suzannah Thoresen on 18 June 1858 and she gave birth to their only child Sigurd on 23 December 1859. The couple lived in very poor financial circumstances and Ibsen became very disenchanted with life in Norway. In 1864, he left Christiania and went to Sorrento in Italy in self-imposed exile. He didn't return to his native land for the next 27 years, and when he returned to it he was a noted, but controversial, playwright.

His next play, Brand (1865), brought him the critical acclaim he sought, along with a measure of financial success, as did the following play, Peer Gynt (1867), to which Edvard Grieg famously composed incidental music and songs. Although Ibsen read excerpts of the Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard and traces of the latter's influence are evident in Brand, it was not until after Brand that Ibsen came to take Kierkegaard seriously. Initially annoyed with his friend Georg Brandes for comparing Brand to Kierkegaard, Ibsen nevertheless read Either/Or and Fear and Trembling. Ibsen's next play Peer Gynt was consciously informed by Kierkegaard.[20][21]

With success, Ibsen became more confident and began to introduce more and more of his own beliefs and judgements into the drama, exploring what he termed the "drama of ideas". His next series of plays are often considered his Golden Age, when he entered the height of his power and influence, becoming the center of dramatic controversy across Europe.

Ibsen moved from Italy to Dresden, Germany, in 1868, where he spent years writing the play he regarded as his main work, Emperor and Galilean (1873), dramatizing the life and times of the Roman emperor Julian the Apostate. Although Ibsen himself always looked back on this play as the cornerstone of his entire works, very few shared his opinion, and his next works would be much more acclaimed. Ibsen moved to Munich in 1875 and began work on his first contemporary realist drama The Pillars of Society, first published and performed in 1877.[22] A Doll's House followed in 1879. This play is a scathing criticism of the marital roles accepted by men and women which characterized Ibsen's society.

Ghosts followed in 1881, another scathing commentary on the morality of Ibsen's society, in which a widow reveals to her pastor that she had hidden the evils of her marriage for its duration. The pastor had advised her to marry her fiancé despite his philandering, and she did so in the belief that her love would reform him. But his philandering continued right up until his death, and his vices are passed on to their son in the form of syphilis. The mention of venereal disease alone was scandalous, but to show how it could poison a respectable family was considered intolerable.

In An Enemy of the People (1882), Ibsen went even further. In earlier plays, controversial elements were important and even pivotal components of the action, but they were on the small scale of individual households. In An Enemy, controversy became the primary focus, and the antagonist was the entire community. One primary message of the play is that the individual, who stands alone, is more often "right" than the mass of people, who are portrayed as ignorant and sheeplike. Contemporary society's belief was that the community was a noble institution that could be trusted, a notion Ibsen challenged. In An Enemy of the People, Ibsen chastised not only the conservatism of society, but also the liberalism of the time. He illustrated how people on both sides of the social spectrum could be equally self-serving. An Enemy of the People was written as a response to the people who had rejected his previous work, Ghosts. The plot of the play is a veiled look at the way people reacted to the plot of Ghosts. The protagonist is a physician in a vacation spot whose primary draw is a public bath. The doctor discovers that the water is contaminated by the local tannery. He expects to be acclaimed for saving the town from the nightmare of infecting visitors with disease, but instead he is declared an 'enemy of the people' by the locals, who band against him and even throw stones through his windows. The play ends with his complete ostracism. It is obvious to the reader that disaster is in store for the town as well as for the doctor.

As audiences by now expected, Ibsen's next play again attacked entrenched beliefs and assumptions; but this time, his attack was not against society's mores, but against overeager reformers and their idealism. Always an iconoclast, Ibsen was equally willing to tear down the ideologies of any part of the political spectrum, including his own.

The Wild Duck (1884) is by many considered Ibsen's finest work, and it is certainly the most complex. It tells the story of Gregers Werle, a young man who returns to his hometown after an extended exile and is reunited with his boyhood friend Hjalmar Ekdal. Over the course of the play, the many secrets that lie behind the Ekdals' apparently happy home are revealed to Gregers, who insists on pursuing the absolute truth, or the "Summons of the Ideal". Among these truths: Gregers' father impregnated his servant Gina, then married her off to Hjalmar to legitimize the child. Another man has been disgraced and imprisoned for a crime the elder Werle committed. Furthermore, while Hjalmar spends his days working on a wholly imaginary "invention", his wife is earning the household income.

Ibsen displays masterful use of irony: despite his dogmatic insistence on truth, Gregers never says what he thinks but only insinuates, and is never understood until the play reaches its climax. Gregers hammers away at Hjalmar through innuendo and coded phrases until he realizes the truth; Gina's daughter, Hedvig, is not his child. Blinded by Gregers' insistence on absolute truth, he disavows the child. Seeing the damage he has wrought, Gregers determines to repair things, and suggests to Hedvig that she sacrifice the wild duck, her wounded pet, to prove her love for Hjalmar. Hedvig, alone among the characters, recognizes that Gregers always speaks in code, and looking for the deeper meaning in the first important statement Gregers makes which does not contain one, kills herself rather than the duck in order to prove her love for him in the ultimate act of self-sacrifice. Only too late do Hjalmar and Gregers realize that the absolute truth of the "ideal" is sometimes too much for the human heart to bear.

Late in his career, Ibsen turned to a more introspective drama that had much less to do with denunciations of society's moral values. In such later plays as Hedda Gabler (1890) and The Master Builder (1892), Ibsen explored psychological conflicts that transcended a simple rejection of current conventions. Many modern readers, who might regard anti-Victorian didacticism as dated, simplistic or hackneyed, have found these later works to be of absorbing interest for their hard-edged, objective consideration of interpersonal confrontation. Hedda Gabler is probably Ibsen's most performed play, with the title role regarded as one of the most challenging and rewarding for an actress even in the present day. Hedda Gabler and A Doll's House center on female protagonists whose almost demonic energy proves both attractive and destructive for those around them, and while Hedda has a few similarities with the character of Nora in A Doll's House, many of today's audiences and theatre critics feel that Hedda's intensity and drive are much more complex and much less comfortably explained than what they view as rather routine feminism on the part of Nora.

Ibsen had completely rewritten the rules of drama with a realism which was to be adopted by Chekhov and others and which we see in the theatre to this day. From Ibsen forward, challenging assumptions and directly speaking about issues has been considered one of the factors that makes a play art rather than entertainment. His works were brought to an English-speaking audience, largely thanks to the efforts of William Archer and Edmund Gosse. These in turn had a profound influence on the young James Joyce who venerates him in his early autobiographical novel "Stephen Hero". Ibsen returned to Norway in 1891, but it was in many ways not the Norway he had left. Indeed, he had played a major role in the changes that had happened across society. Modernism was on the rise, not only in the theatre, but across public life.

Death

On 23 May 1906, Ibsen died in his home at Arbins gade 1 in Kristiania (now Oslo)[23] after a series of strokes in March 1900. When, on 22 May, his nurse assured a visitor that he was a little better, Ibsen spluttered his last words "On the contrary" ("Tvertimod!"). He died the following day at 2:30 p.m.[24]

Ibsen was buried in Vår Frelsers gravlund ("The Graveyard of Our Savior") in central Oslo.[25]

Centenary

The 100th anniversary of Ibsen's death in 2006 was commemorated with an "Ibsen year" in Norway and other countries.[26][27][28] This year the homebuilding company Selvaag also opened Peer Gynt Sculpture Park in Oslo, Norway, in Henrik Ibsen's honour, making it possible to follow the dramatic play Peer Gynt scene by scene. Will Eno's adaptation of Ibsen's Peer Gynt, titled Gnit, had its world premiere at the 37th Humana Festival of New American Plays in March 2013.[29]

On 23 May 2006, The Ibsen Museum in Oslo reopened to the public the house where Ibsen had spent his last eleven years, completely restored with the original interior, colors, and decor.[30]

Legacy

On the occasion of the 100th anniversary of Ibsen's death in 2006, the Norwegian government organised the Ibsen Year, which included celebrations around the world. The NRK produced a miniseries on Ibsen's childhood and youth in 2006, An Immortal Man. Several prizes are awarded in the name of Henrik Ibsen, among them the International Ibsen Award, the Norwegian Ibsen Award and the Ibsen Centennial Commemoration Award.

Every year, since 2008, the annual "Delhi Ibsen Festival", is held in Delhi, India, organized by the Dramatic Art and Design Academy (DADA) in collaboration with The Royal Norwegian Embassy in India. It features plays by Ibsen, performed by artists from various parts of the world in varied languages and styles.[31][32]

Ancestry

Ibsen's ancestry has been a much studied subject, due to his perceived foreignness[33] and due to the influence of his biography and family on his plays. Ibsen often made references to his family in his plays, sometimes by name, or by modelling characters after them.

The oldest documented member of the Ibsen family was ship's captain Rasmus Ibsen (1632–1703) from Stege, Denmark. His son, ship's captain Peder Ibsen became a burgher of Bergen in Norway in 1726.[34] Henrik Ibsen had Danish, German, Norwegian and some distant Scottish ancestry. Most of his ancestors belonged to the merchant class of original Danish and German extraction, and many of his ancestors were ship's captains.

Ibsen's biographer Henrik Jæger famously wrote in 1888 that Ibsen did not have a drop of Norwegian blood in his veins, stating that "the ancestral Ibsen was a Dane". This, however, is not completely accurate; notably through his grandmother Hedevig Paus, Ibsen was descended from one of the very few families of the patrician class of original Norwegian extraction, known since the 15th century. Ibsen's ancestors had mostly lived in Norway for several generations, even though many had foreign ancestry.[35][36]

The name Ibsen is originally a patronymic, meaning "son of Ib" (Ib is a Danish variant of Jacob). The patronymic became "frozen", i.e. it became a permanent family name, in the 17th century. The phenomenon of patronymics becoming frozen started in the 17th century in bourgeois families in Denmark, and the practice was only widely adopted in Norway from around 1900.

| Ancestors of Henrik Ibsen | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Descendants

From his marriage with Suzannah Thoresen, Ibsen had one son, lawyer and government minister Sigurd Ibsen. Sigurd Ibsen married Bergljot Bjørnson, the daughter of Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson. Their only son was Tancred Ibsen, who became a film director and who was married to Lillebil Ibsen. Their only child was diplomat Tancred Ibsen, Jr. Sigurd Ibsen's daughter, Irene Ibsen, married Josias Bille, a member of the Danish ancient noble Bille family. Their son was Danish actor Joen Bille.

Honours

Ibsen was decorated Knight in 1873, Commander in 1892, and with the Grand Cross of the Order of St. Olav in 1893. He received the Grand Cross of the Danish Order of the Dannebrog, and the Grand Cross of the Swedish Order of the Polar Star, and was Knight, First Class of the Order of Vasa.[37]

In 1995, the asteroid 5696 Ibsen was named in his memory.

Works

- 1850 Catiline (Catilina)

- 1850 The Burial Mound also known as The Warrior's Barrow (Kjæmpehøjen)

- 1851 Norma or a Politician's Love (Norma eller en Politikers Kjaerlighed), an eight-page political parody[lower-alpha 1]

- 1852 St. John's Eve (Sancthansnatten)

- 1854 Lady Inger of Oestraat (Fru Inger til Østeraad)

- 1855 The Feast at Solhaug (Gildet paa Solhaug)

- 1856 Olaf Liljekrans (Olaf Liljekrans)

- 1858 The Vikings at Helgeland (Hærmændene paa Helgeland)

- 1862 Love's Comedy (Kjærlighedens Komedie)

- 1863 The Pretenders (Kongs-Emnerne)

- 1866 Brand (Brand)

- 1867 Peer Gynt (Peer Gynt) Translation By William Archer (1911)

- 1869 The League of Youth (De unges Forbund)

- 1871 Digte - only released collection of poetry, included Terje Vigen (written in 1862 but published in Digte from 1871)

- 1873 Emperor and Galilean (Kejser og Galilæer)

- 1877 Pillars of Society (Samfundets Støtter)

- 1879 A Doll's House (Et Dukkehjem)

- 1881 Ghosts (Gengangere)

- 1882 An Enemy of the People (En Folkefiende)

- 1884 The Wild Duck (Vildanden)

- 1886 Rosmersholm (Rosmersholm)

- 1888 The Lady from the Sea (Fruen fra Havet)

- 1890 Hedda Gabler (Hedda Gabler)

- 1892 The Master Builder (Bygmester Solness) Translation By Edmund Grosse and William Archer (1893)

- 1894 Little Eyolf (Lille Eyolf)

- 1896 John Gabriel Borkman (John Gabriel Borkman)

- 1899 When We Dead Awaken (Når vi døde vaagner)

English translations

The authoritative translation in the English language for Ibsen remains the 1928 ten-volume version of the Complete Works of Henrik Ibsen from Oxford University Press. Many other translations of individual plays by Ibsen have appeared since 1928 though none have purported to be a new version of the complete works of Ibsen.

- Ibsen: The Complete Major Prose Plays (Rolf G. Fjelde, translator. Plume: 1978)

- Ibsen - 3 Plays (Kenneth McLeish & Stephen Mulrine, translators. Nick Hern Books: 2005)

- Ibsen's Selected Plays: A Norton Critical Edition (ed. Brian Johnston, Brian Johnston & Rick Davis, translators. W.W. Norton: 2004)

Adaptations

There have been numerous adaptations of Ibsen's work, particularly in film, theatre and music. Notable are Torstein Blixfjord's Terje and Identity of the Soul - two multimedia, film and dance pieces first presented in Yokohama in 2006, based on the poem Terje Vigen.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Though sometimes identified as a play, Norma was never intended for performance. This "juvenile polemical work" was an attack on the Norwegian parliament or Storting, identifying several legislators by name as "fortune hunters". It first appeared anonymously in the satirical magazine Andhrimner.[38] Using play-like dialog and the names of characters from Bellini's opera Norma, Ibsen's hero chooses the "passive" female who represents the government over the heroic title character representing the opposition.[39][40]

References

- ↑ "Ibsen". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ↑ On Ibsen's role as "father of modern drama," see "Ibsen Celebration to Spotlight 'Father of Modern Drama'". Bowdoin College. 23 January 2007. Retrieved 27 March 2007.; on Ibsen's relationship to modernism, see Moi (2006, 1-36)

- ↑ shakespearetheatre.org

- ↑ "Henrik Ibsen – book launch to commemorate the "Father of Modern Drama"".

- ↑ Bonnie G. Smith, "A Doll's House", in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Women in World History, Vol. 2, p. 81, Oxford University Press

- ↑ Klaus Van Den Berg, "Peer Gynt" (review), Theatre Journal 58.4 (2006) 684-687

- 1 2 Valency, Maurice. The Flower and the Castle. Schocken, 1963.

- ↑ Richard Hornby, Ibsen Triumphant, The Hudson Review, Vol. 56, No. 4 (Winter, 2004), pp. 685-691

- ↑ Byatt, AS (15 December 2006). "The age of becoming". The Guardian. London.

- ↑ "Nomination Database".

- ↑ Danish language was the written language of both Denmark and Norway at the time, although it was referred to as Norwegian in Norway and occasionally included some minor differences from the language used in Denmark. Ibsen occasionally used some Norwegianisms in his early work, but in his later work wrote a more standardised Danish, as his plays were published by a Danish publisher and marketed at both Norwegian and Danish audiences in its original language. Cf. Haugen, Einar (1979). "The nuances of Norwegian". Ibsen's Drama: Author to Audience. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota. p. 99. ISBN 0-8166-0896-2.

- ↑ "Henrik Ibsens skrifter".

- ↑ Haugen (1979: 23)

- 1 2 3 4 Michael Meyers. Henrick Ibsen. Chapter one.

- ↑ Theodore Jorgenson (1945). Henrik Ibsen: life and drama. Northfield, Minnesota: St. Olaf College Press

- ↑ Ferguson p. 280

- ↑ Michael Meyers. Henrik Ibsen, Chapter one.

- ↑ Hans Bernhard Jaeger, Henrik Ibsen, 1828-1888: et literært livsbillede, Copenhagen, Gyldendal, 1888

- ↑ Michael Meyes. Henrik Ibsen. Chapters corresponding to individual early plays.

- ↑ Shapiro, Bruce. Divine Madness and the Absurd Paradox. (1990) ISBN 978-0-313-27290-5

- ↑ Downs, Brian. Ibsen: The Intellectual Background (1946)

- ↑ Hanssen, Jens-Morten (10 August 2001). "Facts about Pillars of Society". ibsen.nb.no. Retrieved 8 February 2013.

- ↑ since 2006 The Ibsen Museum (Oslo)

- ↑ Michael Meyer, Ibsen - A Biography, Doubleday 1971, p. 807

- ↑ "Henrik Ibsen (1828 - 1906) - Find A Grave Memorial".

- ↑ norges-bank.no

- ↑ norway.sk

- ↑ Mazur, G.O. One Hundrd Year Commemoration to the Life of Henrik Ibsen, Semenenko Foundation, Andreeff Hall, 12, rue de Montrosier, 92200 Neuilly, Paris, France, 2006.

- ↑ Gioia, Michael. "Premiere of Will Eno's Gnit, Adaptation of Peer Gynt Directed by Les Waters, Opens March 17 at Humana Fest" playbill.com, 17 March 2013

- ↑ "Ibsen.nb.no".

- ↑ "Ibsen time of the year again - Hindustan Times". 22 November 2012. Archived from the original on 27 December 2013. Retrieved 21 December 2013.

- ↑ Daftuar, Swati (24 November 2012). "Showcase: Reinventing Ibsen". Chennai, India: The Hindu. Retrieved 21 December 2013.

- ↑ Johan Kïelland Bergwitz, Henrik Ibsen i sin avstamning: norsk eller fremmed?, Gyldendal Norsk Forlag, 1916

- ↑ Terje Bratberg. "Ibsen – norsk slekt". Store norske leksikon.

- ↑ Henrik Jaeger, Henrik Ibsen. A Critical Biography, Chicago: A.C. McClurg & Co., 1891

- ↑ Bergwitz, Joh. K, Henrik Ibsen i sin avstamning. Norsk eller fremmed?, Nordisk forlag, Gyldendalske boghandel, Christiania and Copenhagen, 1916

- ↑ Amundsen, O. Delphin (1947). Den kongelige norske Sankt Olavs Orden 1847-1947 (in Norwegian). Oslo: Grøndahl. p. 12.

- ↑ Jaeger, Henrik Bernhard (1890). The Life of Henrik Ibsen. London: William Heinemann. p. 64. Retrieved 4 April 2015.

- ↑ Templeton, Joan (1997). Ibsen's Women. Cambridge University Press. p. 340. Retrieved 4 April 2015.

- ↑ Hanssen, Jens-Morten (10 July 2005). "Facts about Norma". National Library of Norway. Retrieved 13 April 2015.

Further reading

- Boyesen, Hjalmar Hjorth, A Commentary on the Works of Henrik Ibsen (New York: Macmillan, 1894)

- Ferguson, Robert (2001) Henrik Ibsen: A New Biography. New York: Dorset Press. ISBN 0760720940

- Goldman, Michael, Ibsen: The Dramaturgy of Fear, Columbia University Press, 1998

- Haugan, Jørgen, Henrik Ibsens Metode:Den Indre Utvikling Gjennem Ibsens Dramatikk (Norwegian: Gyldendal Norsk Forlag. 1977)

- Johnston, Brian: The Ibsen Cycle, Pennsylvania State University Press 1992

- Johnston, Brian, To the Third Empire: Ibsen's Early Plays, University of Minnesota Press (1980)

- Johnston, Brian, Text and Supertext in Ibsen's Drama, Pennsylvania State Press (1988)

- Koht, Halvdan. The Life of Ibsen translated by Ruth Lima McMahon and Hanna Astrup Larsen. W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., New York, 1931

- Krys, Svitlana, A Comparative Feminist Reading of Lesia Ukrainka’s and Henrik Ibsen’s Dramas. Canadian Review of Comparative Literature 34.4 (Dec. 2007 [Sept 2008]): pp.389-409

- Lucas, F. L. The Drama of Ibsen and Strindberg, Cassell, London, 1962. (A useful introduction, giving the biographical background to each play and detailed play-by-play summaries and discussion for the theatre-goer, including the less well-known plays)

- Meyer, Michael. Ibsen. History Press Ltd., Stroud, reprinted 2004

- Moi, Toril (2006) Henrik Ibsen and the Birth of Modernism: Art, Theater, Philosophy. Oxford and New York: Oxford UP. ISBN 978-0-19-920259-1

- Shaw, George Bernard. The Quintessence of Ibsenism (1891). The classic introduction, setting the playwright in his time and place.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Henrik Ibsen |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Henrik Ibsen |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Henrik Ibsen. |

- The Ibsen Society of America Official Website

- ibsen.nb.no

- Ibsen Studies The only international academic journal devoted to Ibsen

- Online course by Ibsen scholar Brian Johnston author of The Ibsen Cycle and To the Third Empire: Ibsen's Early Drama

- Extensive resource in several languages from the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs

- Multilingual edition of all Ibsen Plays in the Bibliotheca Polyglotta

- A Chronological List of Henrik Ibsen's Plays and Japanese Translation

- Digitized books and manuscripts by Ibsen in the National Library of Norway

- Ibsen's Influence on Hitler

- Peer Gynt Sculpture Park, Official Website

- Works by Henrik Ibsen at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Henrik Ibsen at Internet Archive

- Works by Henrik Ibsen at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Henrik Ibsen at Project Gutenberg (the biography by Edmund Gosse)

- Henrik Ibsen - A Bibliography of Criticism and Biography, by Ina Ten Eyck Firkins, from Project Gutenberg

- "Ibsen and His Discontents" - a critical, conservative view of Ibsen's works, written by Theodore Dalrymple

- Ibsen Museum - Former home of the famous playwright is situated in Henrik Ibsen's gate 26, across from the Royal Palace

- Henrik Ibsen: Critical Studies by Georg Brandes (1899). Retrieved January 5, 2017.