Stool guaiac test

| Stool guaiac test | |

|---|---|

| Medical diagnostics | |

Guaiac cards and bottle of developer that contains hydrogen peroxide | |

| MedlinePlus | 003393 |

| HCPCS-L2 | G0394 |

The stool guaiac test or guaiac fecal occult blood test (gFOBT) is one of several methods that detects the presence of fecal occult blood[1] (blood invisible in the feces).[2] The test involves placing a faecal sample on guaiac paper (containing a phenolic compound, alpha-guaiaconic acid, extracted from the wood resin of Guaiacum trees) and applying hydrogen peroxide which, in the presence of blood, yields a blue reaction product within seconds.

The American College of Gastroenterology has recommended the abandoning of gFOBT testing as a colorectal cancer screening tool, in favor of the fecal immunochemical test (FIT).[3] Though the FIT test is preferred, even the guaiac FOB testing of average risk populations may have been sufficient to reduce the mortality associated with colon cancer by about 25%.[4] With this lower efficacy, it was not always cost effective to screen a large population with gFOBT.[5][6][7][8]

Methodology

The stool guaiac test involves fasting from iron supplements, red meat (the blood it contains can turn the test positive), certain vegetables (which contain a chemical with peroxidase properties that can turn the test positive), and vitamin C and citrus fruits (which can turn the test falsely negative) for a period of time before the test. It has been suggested that cucumber, cauliflower and horseradish, and often other vegetables, should be avoided for three days before the test.[9]

In testing, feces are applied to a thick piece of paper attached to a thin film coated with guaiac. Either the patient or medical professional smears a small fecal sample on to the film. The fecal sample is obtained by catching the stool and transferring a sample with an applicator. Digital rectal examination specimens are also used but this method is discouraged for colorectal cancer screening due to very poor performance characteristics.[10]

Both sides of the test card can be peeled open, to access the inner guaiac paper. One side of the card is marked for application of the stool and the other is for the developer fluid.

After applying the feces, one or two drops of hydrogen peroxide are then dripped on to the other side of the film, and it is observed for a rapid blue color change.

Chemistry

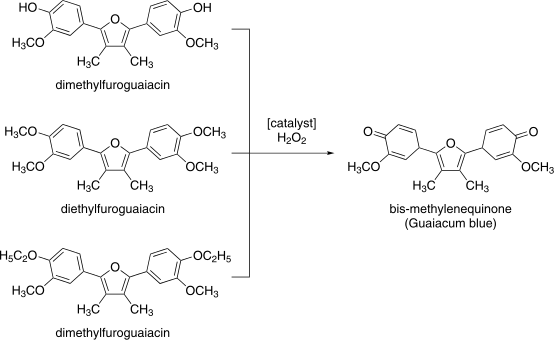

When the hydrogen peroxide is dripped on to the guaiac paper, it oxidizes the alpha-guaiaconic acid to a blue colored quinone.[11][12] Normally, when no blood and no peroxidases or catalases from vegetables are present, this oxidation occurs very slowly. Heme, a component of hemoglobin found in blood, catalyzes this reaction, giving a result in about two seconds. Therefore, a positive test result is one where there is a quick and intense blue color change of the film.

Analytical interpretation

The guaiac test can often be false-positive which is a positive test result when there is in fact no source of bleeding. This is particularly common if the recommended dietary preparation is not followed, as the heme in red meat or the peroxidase or catalase activity in vegetables, especially if uncooked, can cause analytical false positives.

Vitamin C can cause analytical false negatives due to its anti-oxidant properties inhibiting the color reaction.[13][14]

If the card has not been promptly developed, the water content of the feces decreases, and this can reduce the detection of blood.[15] Although rehydration of stored samples can reverse this effect[16] this is not recommended because the test becomes unduly analytically sensitive and thus much less specific.[17][18]

Some stool specimens have a high bile content that causes a green color to show after applying the developer drops. If entirely green, such samples are negative, but if questionably green to blue, such samples are designated positive.[19]

The package insert guidelines from the manufacturers, for example Hemoccult SENSA,[20] recommend that nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID), such as ibuprofen and aspirin, and iron supplements be discontinued for at least several days before the tests. There is a concern that these agents may irritate the body and cause biologically positive tests even in the absence of a more substantial illness,[21][22] but there is some doubt about how frequently this occurs with NSAID medication.[23][24][25] Although both iron and bismuth containing products such as antacids and antidiarrheals can cause dark stools that are occasionally confused as containing blood, actual bleeding from iron is unusual.[26][27]

There is no consensus on whether to stop warfarin before a guaiac test.[28] Even when using anticoagulants a high proportion of positive guaiac tests were found to be due to diagnosable lesions, suggesting anticoagulants may not cause bleeding unless there is an abnormality.[29][30]

Clinical application

The article fecal occult blood (FOB) provides an expanded consideration of the clinical application of FOB tests generally, including other clinical methods, and the comments here are those that relate specifically to the guaiac gFOBT method.

One major use of stool testing for blood is detection of colorectal cancer. However, other possible positive results include: gastroesophageal cancer, GI bleeds, diverticulae, hemorrhoids, anal fissures, colon polyps, ulcerative colitis, Crohn's disease, celiac disease, GERD, esophagitis, peptic ulcers, gastritis, inflammatory bowel disease, vascular ectasias, portal hypertensive gastropathy, aortoenteric fistulas, hemobilia, endometriosis, and trauma.

The stool guaiac test was originally the principal colon cancer screening technology available, but modern tests which look for globin or DNA are now also available. Several recent colon cancer screening guidelines have recommended replacing any older low-sensitivity, guaiac-based fecal occult blood testing (gFOBT) with either newer high-sensitivity guaiac-based fecal occult blood testing (gFOBT) or fecal immunochemical testing (FIT), which tests for globin rather than the heme detected by the guaiac method. The US Multisociety Task Force (MSTF) looked at 6 studies that compared high sensitivity gFOBT (Hemoccult SENSA) to FIT, and concluded that there were no clear difference in overall performance between these methods,[31] and a similar recommendation was made by the National Guideline Clearinghouse (NGC).[32]

Results of a single fecal sample should be interpreted cautiously, as there is a high rate of false negativity associated with the test.[33][34] Using three cards, each on different days, is recommended to improve sensitivity.[35] The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in a 2006–2007 survey found extensive inappropriate use of low sensitivity gFOBT and of single specimens; it is unclear if these widespread suboptimal approaches have since declined.[36] The Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) coding was changed in January 2006 to include CPT code 82270, which indicates that consecutive collection of three stool samples has occurred, either as three single cards or a single triple card. Since January 2007, the US Medicare program reimburses for colorectal cancer screening with gFOBT only when this code is used.[37]

The stool guaiac test method may be preferable to fecal immunochemical testing (FIT) if there is a clinical concern about possible gastric or proximal upper intestinal bleeding.[38] However, although heme breakdown is less than globin during intestinal transit, false negative results can be seen with the stool guaiac tests due to degradation of the peroxidase-activity. This can cause false negative results in upper gastrointestinal bleeding sources, or in right colon adenomas and cancers that have comparable blood losses to positively testing left colon lesions.[39] A positive gFOBT with subsequent negative colonoscopy may lead to an upper endoscopy.[40] It is unclear whether this is an effective intervention if there is a positive gFOBT but no anemia.[41][42][43] Endoscopy when there is a positive gFOBT along with iron deficiency anemia, or iron deficiency anemia on its own, has a higher rate of finding problems.

References

- ↑ "Guidance for Industry and FDA Staff — Review Criteria for Assessment of Qualitative Fecal Occult Blood In Vitro Diagnostic Devices". United States Food and Drug Administration Office of In Vitro Diagnostic Device Evaluation and Safety. August 8, 2007.

- ↑ FDA website publication. Fecal occult blood. Accessioned 2010 October 26 at http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/ProductsandMedicalProcedures/InVitroDiagnostics/HomeUseTests/ucm125834.htm

- ↑ Rex, DK; Johnson, DA; Anderson, JC; Schoenfeld, PS; Burke, CA; Inadomi, JM; American College of, Gastroenterology (Mar 2009). "American College of Gastroenterology guidelines for colorectal cancer screening 2009 [corrected].". The American journal of gastroenterology. 104 (3): 739–50. PMID 19240699. doi:10.1038/ajg.2009.104.

- ↑ Bretthauer M (August 2010). "Evidence for colorectal cancer screening". Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 24 (4): 417–25. PMID 20833346. doi:10.1016/j.bpg.2010.06.005.

- ↑ Mandel JS, Bond JH, Church TR, et al. (1993). "Reducing mortality from colorectal cancer by screening for fecal occult blood". N Engl J Med. 328: 1365–71. PMID 8474513. doi:10.1056/nejm199305133281901.

- ↑ Hardcastle JD, Chamberlain JO, Robinson MH, et al. (1996). "Randomised controlled trial of fecal occult blood screening for colorectal cancer". Lancet. 348: 1472–77. PMID 8942775. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(96)03386-7.

- ↑ Kronborg O, Fenger C, Olsen J, et al. (1996). "Randomised study of screening for colorectal cancer with fecal occult blood test". Lancet. 348: 1467–71. PMID 8942774. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(96)03430-7.

- ↑ Kewenter J, Brevinge H, Engaras B, et al. (1994). "Results of screening,rescreening and follow up in a prospective randomized study for detection of colorectal cancer by fecal occult-blood testing: results of 68,308 subjects". Scand J Gastroenterol. 29: 468–73. PMID 8036464. doi:10.3109/00365529409096840.

- ↑ Beg M, et al. (2002). "Occult Gastrointestinal Bleeding: Detection, Interpretation, and Evaluation" (PDF). JIACM. 3 (2): 153–8.

- ↑ (PDF) http://www.vaoutcomes.org/papers/DRE_CSP_final.pdf. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Kratochvil JF, et al. (1971). "Isolation and characterization of alpha-guaiaconic acid and the nature of guiacum blue". Phytochem. 10: 2529–2531. doi:10.1016/s0031-9422(00)89901-x.

- ↑ Guthlein W, Wielinger H, Rittersdorf W, Werner W. Guaiaconic acid A from guaiac resin, US Patent 4297271 PDF version at http://www.freepatentsonline.com/4297271.html

- ↑ Jaffe RM, Kasten B, Young DS, MacLowry JD (December 1975). "False-negative stool occult blood tests caused by ingestion of ascorbic acid (vitamin C)". Annals of Internal Medicine. 83 (6): 824–6. PMID 1200528. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-83-6-824.

- ↑ Garrick DP, Close JR, McMurray W (October 1977). "Detection of occult blood in faeces". Lancet. 2 (8042): 820–1. PMID 71626. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(77)90753-X.

- ↑ Ahlquist DA, McGill DB, Schwartz S, Taylor WF, Owen RA (May 1985). "Fecal blood levels in health and disease. A study using HemoQuant". N. Engl. J. Med. 312 (22): 1422–8. PMID 3873009. doi:10.1056/NEJM198505303122204.

- ↑ Wells HJ, Pagano JF (1977). "Hemoccult test — reversal of false-negative results due to storage". Gastroenterology. 72: 1148.

- ↑ Macrae FA, St John DJ (May 1982). "Relationship between patterns of bleeding and Hemoccult sensitivity in patients with colorectal cancers or adenomas". Gastroenterology. 82 (5 Pt 1): 891–8. PMID 7060910.

- ↑ Frame PS, Kowulich BA (December 1982). "Stool occult blood screening for colorectal cancer". J Fam Pract. 15 (6): 1071–5. PMID 7142926.

- ↑ Michigan Regional Laboratory System. Fecal occult blood. 2007 August, as web accessioned 2010 October 26 https://docs.google.com/viewer?url=http://www.michigan.gov/documents/Prhemocl_25742_7.wpd__PR_Hemeoccult_bld_in_feces_proc.doc

- ↑ https://docs.google.com/viewer?url=http://www.beckmancoulter.com/literature/ClinDiag/462489.E.pdf

- ↑ Grossman MI, Matsumoto KK, Lichter RJ (March 1961). "Fecal blood loss produced by oral and intravenous administration of various salicylates". Gastroenterology. 40: 383–8. PMID 13709097.

- ↑ Pierson RN, Holt PR, Watson RM, Keating RP (August 1961). "Aspirin and gastrointestinal bleeding. Chromate blood loss studies". Am. J. Med. 31: 259–65. PMID 13735596. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(61)90114-0.

- ↑ Norfleet RG (April 1983). "1,300 mg of aspirin daily does not cause positive fecal hemoccult tests". J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 5 (2): 123–5. PMID 6304182. doi:10.1097/00004836-198304000-00006.

- ↑ Doubilet P, Donowitz M, Pauker SG (1982). "Evaluation for colon cancer in patients with occult fecal blood loss while taking aspirin: a Bayesian viewpoint". Med Decis Making. 2 (2): 147–60. PMID 7167043. doi:10.1177/0272989x8200200206.

- ↑ Bahrt KM, Korman LY, Nashel DJ (November 1984). "Significance of a positive test for occult blood in stools of patients taking anti-inflammatory drugs". Arch. Intern. Med. 144 (11): 2165–6. PMID 6333854. doi:10.1001/archinte.144.11.2165.

- ↑ Laine LA, Bentley E, Chandrasoma P (February 1988). "Effect of oral iron therapy on the upper gastrointestinal tract. A prospective evaluation". Dig. Dis. Sci. 33 (2): 172–7. PMID 3257437. doi:10.1007/BF01535729.

- ↑ Anderson GD, Yuellig TR, Krone RE (May 1990). "An investigation into the effects of oral iron supplementation on in vivo Hemoccult stool testing". Am. J. Gastroenterol. 85 (5): 558–61. PMID 2186616.

- ↑ Imperiale TF (September 2010). "Continue or discontinue warfarin for fecal occult blood testing in 2010? Does the published evidence provide an answer?". Am. J. Gastroenterol. 105 (9): 2036–9. PMID 20818354. doi:10.1038/ajg.2010.269.

- ↑ Jaffin BW, Bliss CM, LaMont JT (August 1987). "Significance of occult gastrointestinal bleeding during anticoagulation therapy". Am. J. Med. 83 (2): 269–72. PMID 3497580. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(87)90697-8.

- ↑ Barada K, Abdul-Baki H, El Hajj II, Hashash JG, Green PH (January 2009). "Gastrointestinal bleeding in the setting of anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy". J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 43 (1): 5–12. PMID 18607297. doi:10.1097/MCG.0b013e31811edd13.

- ↑ Levin B, Lieberman DA, McFarland B, et al. (May 2008). "Screening and surveillance for the early detection of colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps, 2008: a joint guideline from the American Cancer Society, the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and the American College of Radiology". Gastroenterology. 134 (5): 1570–95. PMID 18384785. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2008.02.002. Also published as Levin B; Lieberman DA; McFarland B; et al. (2008). "Screening and surveillance for the early detection of colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps, 2008: a joint guideline from the American Cancer Society, the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and the American College of Radiology". CA Cancer J Clin. 58 (3): 130–60. PMID 18322143. doi:10.3322/CA.2007.0018.

- ↑ National Guideline Clearinghouse (NGC), a U.S. government-provided resource for evidence-based clinical practice guidelines, at http://www.guideline.gov/summary/summary.aspx?doc_id=14345

- ↑ http://www.practicalgastro.com/pdf/June07/June07AllisonArticle.pdf

- ↑ Collins JF, Lieberman DA, Durbin TE, Weiss DG (January 2005). "Accuracy of screening for fecal occult blood on a single stool sample obtained by digital rectal examination: a comparison with recommended sampling practice". Annals of Internal Medicine. 142 (2): 81–5. PMID 15657155. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-142-2-200501180-00006.

- ↑ "Screening average risk patients for colorectal cancer — B01". Retrieved 2007-10-25.

- ↑ Nadel MR, Berkowitz Z, Klabunde CN, Smith RA, Coughlin SS, White MC (August 2010). "Fecal occult blood testing beliefs and practices of U.S. primary care physicians: serious deviations from evidence-based recommendations". J Gen Intern Med. 25 (8): 833–9. PMC 2896587

. PMID 20383599. doi:10.1007/s11606-010-1328-7.

. PMID 20383599. doi:10.1007/s11606-010-1328-7. - ↑ Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Colorectal cancer: Preventable, treatable and beatable: Medicare coverage and billing for colorectal cancer screening. Medicare Learning Network Matters SE0710. www.cms.hhs.gov/MLNMattersArticles/downloads/SE0710.pdf Accessioned 2010 November 1

- ↑ Rockey DC (July 1999). "Occult gastrointestinal bleeding". N. Engl. J. Med. 341 (1): 38–46. PMID 10387941. doi:10.1056/NEJM199907013410107.

- ↑ Herzog P, Holtermüller KH, Preiss J, et al. (November 1982). "Fecal blood loss in patients with colonic polyps: a comparison of measurements with 51chromium-labeled erythrocytes and with the Haemoccult test". Gastroenterology. 83 (5): 957–62. PMID 7117808.

- ↑ Rockey DC (December 2005). "Occult gastrointestinal bleeding". Gastroenterol. Clin. North Am. 34 (4): 699–718. PMID 16303578. doi:10.1016/j.gtc.2005.08.010.

- ↑ Zappa M, Visioli CB, Ciatto S, et al. (April 2007). "Gastric cancer after positive screening faecal occult blood testing and negative assessment". Dig Liver Dis. 39 (4): 321–6. PMID 17314076. doi:10.1016/j.dld.2006.11.010.

- ↑ Bond JH (April 2007). "FOBT is not an effective way to screen for gastric cancer". Dig Liver Dis. 39 (4): 327–8. PMID 17317346. doi:10.1016/j.dld.2006.12.013.

- ↑ Allard J, Cosby R, Del Giudice ME, Irvine EJ, Morgan D, Tinmouth J (February 2010). "Gastroscopy following a positive fecal occult blood test and negative colonoscopy: systematic review and guideline". Can. J. Gastroenterol. 24 (2): 113–20. PMC 2852233

. PMID 20151070.

. PMID 20151070.