Helical antenna

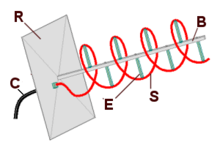

(B) Central support,

(C) Coaxial cable feedline,

(E) Insulating supports for the helix,

(R) Reflector ground plane,

(S) Helical radiating wire

A helical antenna is an antenna consisting of a conducting wire wound in the form of a helix. In most cases, helical antennas are mounted over a ground plane. The feed line is connected between the bottom of the helix and the ground plane. Helical antennas can operate in one of two principal modes — normal mode or axial mode.

In the normal mode or broadside helical antenna, the diameter and the pitch of the aerial are small compared with the wavelength. The antenna acts similarly to an electrically short dipole or monopole, and the radiation pattern, similar to these antennas is omnidirectional, with maximum radiation at right angles to the helix axis. The radiation is linearly polarised parallel to the helix axis. These are used for compact antennas for portable and mobile two-way radios, and for UHF television broadcasting antennas.

In the axial mode or end-fire helical antenna, the diameter and pitch of the helix are comparable to a wavelength. The antenna functions as a directional antenna radiating a beam off the ends of the helix, along the antenna's axis. It radiates circularly polarised radio waves. These are used for satellite communication.

Normal-mode helical

If the circumference of the helix is significantly less than a wavelength and its pitch (axial distance between successive turns) is significantly less than a quarter wavelength, the antenna is called a normal-mode helix. The antenna acts similar to a monopole antenna, with an omnidirectional radiation pattern, radiating equal power in all directions perpendicular to the antenna's axis. However, because of the inductance added by the helical shape, the antenna acts like a inductively loaded monopole; at its resonant frequency it is shorter than a quarter-wavelength long. Therefore, normal-mode helices can be used as electrically short monopoles, an alternative to center- or base-loaded whip antennas, in applications where a full sized quarter-wave monopole would be too big. As with other electrically short antennas, the gain, and thus the communication range, of the helix will be less than that of a full sized antenna. Their compact size makes "helicals" useful as antennas for mobile and portable communications equipment on the HF, VHF, and UHF bands.

An effect of using a helical conductor rather than a straight one is that the matching impedance is changed from the nominal 50 ohms to between 25 and 35 ohms base impedance. This does not seem to be adverse to operation or matching with a normal 50 ohm transmission line, provided the connecting feed is the electrical equivalent of a 1/2 wavelength at the frequency of operation.

Another example of the type as used in mobile communications is "spaced constant turn" in which two or more different linear windings are wound on a single former and spaced so as to provide an efficient balance between capacitance and inductance for the radiating element at a particular resonant frequency.

Many examples of this type have been used extensively for 27 MHz CB radio with a wide variety of designs originating in the US and Australia in the late 1960s. Multi-frequency versions with plug-in taps have become the mainstay for multi-band Single-sideband modulation (SSB) HF communications.

Most examples were wound with copper wire using a fiberglass rod as a former. This flexible radiator is then covered with heat-shrink tubing which provides a resilient and rugged waterproof covering for the finished mobile antenna.

These popular designs are still in common use as of 2010 and have been universally adapted as standard FM receiving antennas for many factory produced motor vehicles as well as the existing basic style of aftermarket HF and VHF mobile helical. The most common use for broadside helixes is in the "rubber ducky antenna" found on most portable VHF and UHF radios.

Helical broadcasting antennas

Specialized normal-mode helical antennas are used for FM radio and television broadcasting on the VHF and UHF bands.

Axial-mode helical

When the helix circumference is near the wavelength of operation, the antenna operates in axial mode. This is a nonresonant traveling wave mode, in which instead of standing waves, the waves of current and voltage travel in one direction, up the helix. Instead of radiating linearly polarized waves normal to the antenna's axis, it radiates a beam of radio waves with circular polarisation along the axis, off the ends of the antenna. The main lobes of the radiation pattern are along the axis of the helix, off both ends. Since in a directional antenna only radiation in one direction is wanted, the other end of the helix is terminated in a flat metal sheet or screen reflector to reflect the waves forward.

In radio transmission, circular polarisation is often used where the relative orientation of the transmitting and receiving antennas cannot be easily controlled, such as in animal tracking and spacecraft communications, or where the polarisation of the signal may change, so end-fire helical antennas are frequently used for these applications. Since large helices are difficult to build and unwieldy to steer and aim, the design is commonly employed only at higher frequencies, ranging from VHF up to microwave.

The helix in the antenna can twist in two possible directions: right-handed or left-handed, as defined by the right-hand rule. In an axial-mode helical antenna the direction of twist of the helix determines the polarisation of the radio waves. Two mutually incompatible conventions are in use for describing waves with circular polarisation, so the relationship between the handedness (left or right) of a helical antenna, and the type of circularly-polarised radiation it emits cannot be stated without ambiguity. Helical antennas can receive signals with any type of linear polarisation, such as horizontal or vertical polarisation, but when receiving circularly polarised signals the handedness of the receiving antenna must be the same as the transmitting antenna; left-hand polarised antennas suffer a severe loss of gain when receiving right-circularly-polarised signals, and vice versa.

The dimensions of the helix are determined by the wavelength λ of the radio waves used, which depends on the frequency. In order to operate in axial-mode, the circumference should be equal to the wavelength.[1] The pitch angle should be 13 degrees, which is a pitch distance (distance between each turn) of 0.23 times the circumference, which means the spacing between the coils should be approximately one-quarter of the wavelength (λ/4). The number of turns in the helix determines how directional the antenna is: more turns improves the gain in the direction of its axis at both ends (or at 1 end when a ground plate is used), at a cost of gain in the other directions. When C<λ it operates more in normal mode where the gain direction is a donut shape to the sides instead of out the ends.

Terminal impedance in axial mode ranges between 100 and 200 ohms, approximately

where C is the circumference of the helix, and λ is the wavelength. Impedance matching (when C=λ) to standard 50 or 75 ohm coaxial cable is often done by a quarter wave stripline section acting as an impedance transformer between the helix and the ground plate.

The maximum directive gain is approximately:

where N is the number of turns and S is the spacing between turns. Most designs use C=λ and S=0.23*C, so the gain is typically G=0.8*N. In decibels, the gain is .

The half-power beamwidth is:

The beamwidth between nulls is:

The gain of the helical antenna strongly depends on the reflector.[3] The above classical formulas assume that the reflector has the form of a circular resonator (a circular plate with a rim) and the pitch angle is optimal for this type of reflector. Nevertheless, these formulas overestimate the gain for several dB.[4] The optimal pitch that maximizes the gain for a flat ground plane is in the range from 3° to 10° and it depends on the wire radius and antenna length.[4]

See also

References

- ↑ https://www.cv.nrao.edu/~demerson/helixgain/helix.htm

- 1 2 Tomasi, Wayne (2004). Electronic Communication Systems - Fundamentals Through Advanced. Jurong, Singapore: Pearson Education SE Asia Ltd. ISBN 981-247-093-X.

- ↑ Djordjević, A.R., Zajić, A.G., and Ilić, M.M., “Enhancing the gain of helical antennas by shaping the ground conductor”, IEEE Antennas and Wireless Propagation Letters, Vol. 5, 2006, pp. 138-140

- 1 2 Djordjević, A.R., Zajić, A.G., Ilić, M.M., and Stueber, G.L., “Optimization of helical antennas“, IEEE Antennas and Propagation Magazine, vol. 48, no. 6, December 2006, pp. 107-115

- General

- John D. Kraus and Ronald J. Marhefka, "Antennas: For All Applications, Third Edition", 2002, McGraw-Hill Higher Education

- Constantine Balanis, "Antenna Theory, Analysis and Design", 1982, John Wiley and Sons

- Warren Stutzman and Gary Thiele, "Antenna Theory and Design, 2nd. Ed.", 1998, John Wiley and Sons

External links

- Helical Antennas Antenna-Theory