Helen Cordero

| Helen Cordero | |

|---|---|

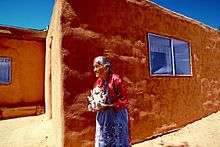

Helen Cordero, 1986 | |

| Born |

Helen Quintano June 15, 1915 Cochiti Pueblo, New Mexico |

| Died | July 24, 1994 (aged 79)[1] |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation | Traditional potter |

| Known for | Storyteller pottery figurines |

| Spouse(s) | George Cordero |

| Children | Antonita "Toni" Cordero Suina, Dolores Peshlakai, Jimmy Cordero, George Cordero, Leonard Trujillo |

| Parent(s) | Quintana and Coroline Quintana-Pecos |

| Relatives | Grandchildren, Delbert Moses Trancosa,Tim Cordero, Buffy Cordero, Kevin Peshlakai, Tia Cordero, Kevin Peshlakai, Ivan Trujillo, Evon Trujillo, Robert Trujillo, Jeanette Trujillo, Del Trancosa; son-in-law Del Trancosa, foster daughters-in-law Kathy Trujillo and Mary Trujillo |

| Awards | Santa Fe Living Treasure, 1985; National Heritage Fellow, 1986 |

Helen Cordero (June 15, 1915 – July 24, 1994) was a Cochiti Pueblo potter from Cochiti, New Mexico. She was renowned for her storyteller pottery figurines, a motif she invented,[2] based upon the traditional "singing mother" motif.

Background

Cordero was a lifelong resident of Cochiti Pueblo. She married Fred Cordero, an artist, drum-maker, and governor of Cochiti Pueblo, and they had four children.[3] She first learned to create leatherwork, then in the 1950s started creating pottery birds and animals that her husband painted.[4] It is said that Helen's aunt suggested clay as a medium over the more expensive leather. She also recommended figures after the early attempts by Helen at bowls and jars were misshapen.[5] According to one account, she was commissioned by the Anglo designer and collector Alexander Girard to create the first Storyteller.[6] Yet in a 1981 article Cordero said she created the first Storyteller on her own in 1964. "I made some more of my Storytellers with lots of children climbing on him to listen, then I took them up to the Santo Domingo Feast Day" where Alexander Girard bought them.[4] Alexander Girard was a patron who purchased her early work.[7] Not long after Helen started her dolls, Gerard asked her to increase her yield and the size of her figures. This request ultimately terminated in a 250-piece Nativity set. It is suggested the Gerard also proposed Helen should fashion a larger figure seated with children. Helen mulled over the idea, and thought of her grandfather, Santiago Quintana, who she remembered as a great storyteller. Helen's grandfather would in part inspire her first Storyteller surrounded by five grandchildren.[5]

Cordero "followed a traditional way of life including digging her own clay and preparing her own pigments."[8] She used three types of clay, all sourced near Cochiti Pueblo, and clay and plant materials for paint.[3] Over time, Helen's finish became more refined, and she made her children separately instead of from the primary piece of clay allowing for her to vary their placement around the storyteller. As Helen's work progressed, she ultimately developed the trademark face for which her dolls are now known.[5]

After 1964, her family members joined her in making Storyteller figurines.[9]

She would

"work outdoors in warm weather and at her kitchen table in the winter. Her husband and son drove one hundred miles to bring home the cedar wood she used to fire her pieces ... on an open iron grate behind her house."[10]

Her Storyteller design became popular with other pottery-makers, who have created variations, including animal storytellers.[4] To distinguish her work and to fulfill the expectations of some collectors, Helen began signing her works. After the success of the Storyteller, Helen eventually drew more from her experiences and went on to develop other types including, drummers, singing mothers, Pueblo father, and Hopi maiden.[5]

Helen Cordero was honored as a Santa Fe Living Treasure in 1985.[10] In 1986 she was made a National Heritage Fellow.

Helen Cordero Primary School, in Albuquerque, New Mexico, is named after her.[11]

Collections

Cordero's work is found in the Museum of International Folk Art and the New Mexico Museum of Art in Santa Fe, New Mexico, the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, DC, the Heard Museum in Phoenix, and the Brooklyn Museum.

References

- ↑ "Helen Cordero: Death Record from the Social Security Death Index (SSDI)". GenealogyBank. Retrieved 2014-02-20.

- ↑ Smith, Jack (30 March 2005). "OLD AND NEW; The History Is Here, but the Action Is Elsewhere". The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-10-01.

- 1 2 Babcock, Barbara (December 1978). "Helen Cordero, The Storyteller Lady". New Mexico Magazine.

- 1 2 3 Love, Marian (December 1981). "Helen Cordero's Dolls". The Santa Fean.

- 1 2 3 4 Jones, Michael Owen (1997). "How Can We Apply Event Analysis to "Material Behavior," and Why Should We?". Western Folklore. 56, 3/4: 204 – via JSTOR.

- ↑ Peterson, Susan (1997). Pottery by American Indian Women: The Legacy of Generations. Abbeville Press. p. 92.

- ↑ "Helen Cordero, Cochiti Pueblo". Adobe Gallery, Santa Fe. Retrieved 2014-02-20.

- ↑ "Helen Cordero - Artist, Fine Art, Auction Records, Prices, Biography for Helen Cordero". Ask Art, the Artist's Bluebook. Retrieved 2014-02-20.

- ↑ "Antonita Cordero Suina (b. 1948 - )". Adobe Gallery, Santa Fe. Retrieved 2014-02-20.

- 1 2 "Cordero, Helen". Santa Fe Living Treasures – Elder Stories. Retrieved 2014-02-20.

- ↑ "Helen Cordero Primary School". Retrieved 2014-02-20.

Further reading

- Babcock, Barbara A.; Monthan, Guy; Monthan, Doris Born (1986). The Pueblo Storyteller: Development of a figurative ceramic tradition. Tucson, Arizona: University of Arizona Press. ISBN 978-0-8165-0870-9.

- Howard, Nancy Shroyer (1995). Helen Cordero and the Storytellers of Cochiti People. Worcester, Massachusetts: Davis Publications. ISBN 978-0-87192-295-3.

- Guy and Doris Monthan. (1975) Art and Indian Individualist: Profile of 17 Southwest Native American Artists. Flagstaff, Arizona. Northland Press. ISBN 0-87358-137-7. LCCCN 74-31544