Heinrich Hertz

| Heinrich Hertz | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

Heinrich Rudolf Hertz 22 February 1857 Hamburg, German Confederation |

| Died |

1 January 1894 (aged 36) Bonn, German Empire |

| Residence | Germany |

| Nationality | German |

| Fields |

Physics Electronic Engineering |

| Institutions |

University of Kiel University of Karlsruhe University of Bonn |

| Alma mater |

University of Munich University of Berlin |

| Doctoral advisor | Hermann von Helmholtz |

| Doctoral students | Vilhelm Bjerknes |

| Known for |

Electromagnetic radiation Photoelectric effect Hertz's principle of least curvature |

| Notable awards |

Matteucci Medal (1888) Rumford Medal (1890) |

|

Signature  | |

Heinrich Rudolf Hertz (German: [hɛɐʦ]; 22 February 1857 – 1 January 1894) was a German physicist who first conclusively proved the existence of the electromagnetic waves theorized by James Clerk Maxwell's electromagnetic theory of light. The unit of frequency — cycle per second — was named the "hertz" in his honor.[1]

Biography

Heinrich Rudolf Hertz was born in 1857 in Hamburg, then a sovereign state of the German Confederation, into a prosperous and cultured Hanseatic family. His father Gustav Ferdinand Hertz (originally named David Gustav Hertz) (1827–1914) was a barrister and later a senator.[2] His mother was Anna Elisabeth Pfefferkorn.

Hertz's father converted from Judaism to Christianity[3][4] in 1834.[5] His mother's family was a Lutheran[6] pastor's family.

While studying at the Gelehrtenschule des Johanneums in Hamburg, Hertz showed an aptitude for sciences as well as languages, learning Arabic and Sanskrit. He studied sciences and engineering in the German cities of Dresden, Munich and Berlin, where he studied under Gustav R. Kirchhoff and Hermann von Helmholtz. In 1880, Hertz obtained his PhD from the University of Berlin, and for the next three years remained for post-doctoral study under Helmholtz, serving as his assistant. In 1883, Hertz took a post as a lecturer in theoretical physics at the University of Kiel. In 1885, Hertz became a full professor at the University of Karlsruhe.

In 1886, Hertz married Elisabeth Doll, the daughter of Dr. Max Doll, a lecturer in geometry at Karlsruhe. They had two daughters: Johanna, born on 20 October 1887 and Mathilde, born on 14 January 1891, who went on to become a notable biologist. During this time Hertz conducted his landmark research into electromagnetic waves.

Hertz took a position of Professor of Physics and Director of the Physics Institute in Bonn on 3 April 1889, a position he held until January 1894. During this time he worked on theoretical mechanics with his work published in the book Die Prinzipien der Mechanik in neuem Zusammenhange dargestellt (The Principles of Mechanics Presented in a New Form), published posthumously in 1894.

Death

In 1892, Hertz was diagnosed with an infection (after a bout of severe migraines) and underwent operations to treat the illness. He died of granulomatosis with polyangiitis at the age of 36 in Bonn, Germany in 1894, and was buried in the Ohlsdorf Cemetery in Hamburg.[7][8][9][10]

Hertz's wife, Elisabeth Hertz née Doll (1864–1941), did not remarry. Hertz left two daughters, Johanna (1887–1967) and Mathilde (1891–1975). Hertz's daughters never married and he has no descendants.[11]

Scientific work

Meteorology

Hertz always had a deep interest in meteorology, probably derived from his contacts with Wilhelm von Bezold (who was his professor in a laboratory course at the Munich Polytechnic in the summer of 1878). However, Hertz did not contribute much to the field himself except some early articles as an assistant to Helmholtz in Berlin, including research on the evaporation of liquids, a new kind of hygrometer, and a graphical means of determining the properties of moist air when subjected to adiabatic changes.[12]

Contact mechanics

In 1886–1889, Hertz published two articles on what was to become known as the field of contact mechanics. Hertz is well known for his contributions to the field of electrodynamics (see below); however, most papers that look into the fundamental nature of contact cite his two papers as a source for some important ideas. Joseph Valentin Boussinesq published some critically important observations on Hertz's work, nevertheless establishing this work on contact mechanics to be of immense importance. His work basically summarises how two axi-symmetric objects placed in contact will behave under loading, he obtained results based upon the classical theory of elasticity and continuum mechanics. The most significant failure of his theory was the neglect of any nature of adhesion between the two solids, which proves to be important as the materials composing the solids start to assume high elasticity. It was natural to neglect adhesion in that age as there were no experimental methods of testing for it.

To develop his theory Hertz used his observation of elliptical Newton's rings formed upon placing a glass sphere upon a lens as the basis of assuming that the pressure exerted by the sphere follows an elliptical distribution. He used the formation of Newton's rings again while validating his theory with experiments in calculating the displacement which the sphere has into the lens. K. L. Johnson, K. Kendall and A. D. Roberts (JKR) used this theory as a basis while calculating the theoretical displacement or indentation depth in the presence of adhesion in 1971.[13] Hertz's theory is recovered from their formulation if the adhesion of the materials is assumed to be zero. Similar to this theory, however using different assumptions, B. V. Derjaguin, V. M. Muller and Y. P. Toporov published another theory in 1975, which came to be known as the DMT theory in the research community, which also recovered Hertz's formulations under the assumption of zero adhesion. This DMT theory proved to be rather premature and needed several revisions before it came to be accepted as another material contact theory in addition to the JKR theory. Both the DMT and the JKR theories form the basis of contact mechanics upon which all transition contact models are based and used in material parameter prediction in nanoindentation and atomic force microscopy. So Hertz's research from his days as a lecturer, preceding his great work on electromagnetism, which he himself considered with his characteristic soberness to be trivial, has come down to the age of nanotechnology.

Electromagnetic waves

During Hertz's studies in 1879 Helmholtz suggested that Hertz's doctoral dissertation be on testing Maxwell's theory of electromagnetism, published in 1865, which predicted the existence of electromagnetic waves moving at the speed of light, and predicted that light itself was just such a wave. Helmholtz had also proposed the "Berlin Prize" problem that year at the Prussian Academy of Sciences for anyone who could experimentally prove an electromagnetic effect in the polarization and depolarization of insulators, something predicted by Maxwell's theory.[15][16] Helmholtz was sure Hertz was the most likely candidate to win it.[16] Not seeing any way to build an apparatus to experimentally test this, Hertz thought it was too difficult, and worked on electromagnetic induction instead. Hertz did produce an analysis of Maxwell's equations during his time at Kiel, showing they did have more validity than the then prevalent "action at a distance" theories.[17]

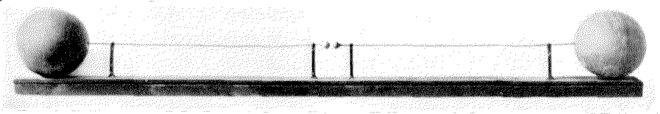

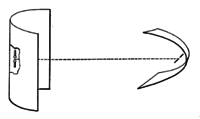

After Hertz received his professorship at Karlsruhe he was experimenting with a pair of Riess spirals in the autumn of 1886 when he noticed that discharging a Leyden jar into one of these coils would produce a spark in the other coil. With an idea on how to build an apparatus, Hertz now had a way proceed with the "Berlin Prize" problem of 1879 on proving Maxwell's theory (although the actual prize had expired uncollected in 1882).[18][19] He used a Ruhmkorff coil-driven spark gap and one-meter wire pair as a radiator. Capacity spheres were present at the ends for circuit resonance adjustments. His receiver was a simple half-wave dipole antenna with a micrometer spark gap between the elements. This experiment produced and received what are now called radio waves in the very high frequency range.

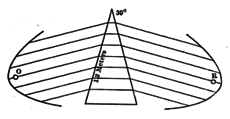

Between 1886 and 1889 Hertz would conduct a series of experiments that would prove the effects he was observing were results of Maxwell's predicted electromagnetic waves. Starting in November 1887 with his paper "On Electromagnetic Effects Produced by Electrical Disturbances in Insulators", Hertz would send a series of papers to Helmholtz at the Berlin Academy, including papers in 1888 that showed transverse free space electromagnetic waves traveling at a finite speed over a distance.[19][20] In the apparatus Hertz used, the electric and magnetic fields would radiate away from the wires as transverse waves. Hertz had positioned the oscillator about 12 meters from a zinc reflecting plate to produce standing waves. Each wave was about 4 meters long. Using the ring detector, he recorded how the wave's magnitude and component direction varied. Hertz measured Maxwell's waves and demonstrated that the velocity of these waves was equal to the velocity of light. The electric field intensity, polarity and reflection of the waves were also measured by Hertz. These experiments established that light and these waves were both a form of electromagnetic radiation obeying the Maxwell equations. Hertz also described the "Hertzian cone", a type of wave-front propagation through various media.

Hertz helped establish the photoelectric effect (which was later explained by Albert Einstein) when he noticed that a charged object loses its charge more readily when illuminated by ultraviolet radiation (UV). In 1887, he made observations of the photoelectric effect and of the production and reception of electromagnetic (EM) waves, published in the journal Annalen der Physik. His receiver consisted of a coil with a spark gap, whereby a spark would be seen upon detection of EM waves. He placed the apparatus in a darkened box to see the spark better. He observed that the maximum spark length was reduced when in the box. A glass panel placed between the source of EM waves and the receiver absorbed UV that assisted the electrons in jumping across the gap. When removed, the spark length would increase. He observed no decrease in spark length when he substituted quartz for glass, as quartz does not absorb UV radiation. Hertz concluded his months of investigation and reported the results obtained. He did not further pursue investigation of this effect, nor did he make any attempt at explaining how the observed phenomenon was brought about.

Hertz did not realize the practical importance of his radio wave experiments. He stated that,

- "It's of no use whatsoever[...] this is just an experiment that proves Maestro Maxwell was right—we just have these mysterious electromagnetic waves that we cannot see with the naked eye. But they are there."[22][23][24]

Asked about the ramifications of his discoveries, Hertz replied,

- "Nothing, I guess."[22]

Hertz's proof of the existence of airborne electromagnetic waves led to an explosion of experimentation with this new form of electromagnetic radiation, which was called "Hertzian waves" until around 1910 when the term "radio waves" became current. Within 10 years researchers such as Oliver Lodge, Ferdinand Braun, and Guglielmo Marconi employed radio waves in the first wireless telegraphy radio communication systems, leading to radio broadcasting, and later television. Today radio is an essential technology in global telecommunication networks, and the transmission medium underlying modern wireless devices.

Cathode rays

In 1892, Hertz began experimenting and demonstrated that cathode rays could penetrate very thin metal foil (such as aluminium). Philipp Lenard, a student of Heinrich Hertz, further researched this "ray effect". He developed a version of the cathode tube and studied the penetration by X-rays of various materials. Philipp Lenard, though, did not realize that he was producing X-rays. Hermann von Helmholtz formulated mathematical equations for X-rays. He postulated a dispersion theory before Röntgen made his discovery and announcement. It was formed on the basis of the electromagnetic theory of light (Wiedmann's Annalen, Vol. XLVIII). However, he did not work with actual X-rays.

Nazi persecution

Heinrich Hertz was a Lutheran throughout his life and would not have considered himself Jewish, as his father's family had all converted to Lutheranism[26] when his father was still in his childhood (aged seven) in 1834.[5]

Nevertheless, when the Nazi regime gained power decades after Hertz's death, his portrait was removed by them from its prominent position of honor in Hamburg's City Hall (Rathaus) because of his partly Jewish ethnic ancestry. (The painting has since been returned to public display.[27])

Hertz's widow and daughters left Germany in the 1930s and went to England.

Legacy and honors

Heinrich Hertz's nephew Gustav Ludwig Hertz was a Nobel Prize winner, and Gustav's son Carl Helmut Hertz invented medical ultrasonography. His daughter Mathilde Carmen Hertz was a well-known biologist and comparative psychologist.

The SI unit hertz (Hz) was established in his honor by the International Electrotechnical Commission in 1930 for frequency, an expression of the number of times that a repeated event occurs per second. It was adopted by the CGPM (Conférence générale des poids et mesures) in 1960, officially replacing the previous name, "cycles per second" (cps).

In 1928 the Heinrich-Hertz Institute for Oscillation Research was founded in Berlin. Today known as the Fraunhofer Institute for Telecommunications, Heinrich Hertz Institute, HHI.

In 1969 (East Germany), a Heinrich Hertz memorial medal[28] was cast. The IEEE Heinrich Hertz Medal, established in 1987, is "for outstanding achievements in Hertzian waves [...] presented annually to an individual for achievements which are theoretical or experimental in nature".

A crater that lies on the far side of the Moon, just behind the eastern limb, is named in his honor. The Hertz market for radio electronics products in Nizhny Novgorod, Russia, is named after him. The Heinrich-Hertz-Turm radio telecommunication tower in Hamburg is named after the city's famous son.

Hertz is honored by Japan with a membership in the Order of the Sacred Treasure, which has multiple layers of honor for prominent people, including scientists.[29]

Heinrich Hertz has been honored by a number of countries around the world in their postage issues, and in post-World War II times has appeared on various German stamp issues as well.

On his birthday in 2012, Google honored Hertz with a Google doodle, inspired by his life's work, on its home page.[30][31]

See also

|

|

References

- ↑ IEC History. Iec.ch.

- ↑ "Biography: Heinrich Rudolf Hertz". MacTutor History of Mathematics archive. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- ↑ Robertson, Struan. "Buildings Integral to the Former Life and/or Persecution of Jews in Hamburg". uni-hamburg.de. Archived from the original on 27 March 2012. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- ↑ Heinrich Rudolf Hertz. ur5eaw.com

- 1 2 Wolff, Stefan L. (2008-01-04) Juden wider Willen – Wie es den Nachkommen des Physikers Heinrich Hertz im NS-Wissenschaftsbetrieb erging. Jüdische Allgemeine.

- ↑ Mitchell, Curtis (1970). Cavalcade of broadcasting. Follett Pub. Co.

- ↑ "Heinrich Rudolf Hertz". Find a Grave. Retrieved 22 August 2014.

- ↑ Hamburger Friedhöfe » Ohlsdorf » Prominente. Friedhof-hamburg.de. Retrieved on 22 August 2014.

- ↑ Plan Ohlsdorfer Friedhof (Map of Ohlsdorf Cemetery). friedhof-hamburg.de.

- ↑ IEEE Institute, Did You Know? Historical ‘Facts’ That Are Not True

- ↑ Susskind, Charles. (1995). Heinrich Hertz: A Short Life. San Francisco: San Francisco Press. ISBN 0-911302-74-3

- ↑ Mulligan, J. F.; Hertz, H. G. "An unpublished lecture by Heinrich Hertz: "On the energy balance of the Earth’’". American Journal of Physics. 65: 36–45. Bibcode:1997AmJPh..65...36M. doi:10.1119/1.18565.

- ↑ Johnson, K. L.; Kendall, K.; Roberts, A. D. (1971). "Surface energy and contact of elastic solids" (PDF). Proceedings of the Royal Society A. 324 (1558): 301–313. Bibcode:1971RSPSA.324..301J. doi:10.1098/rspa.1971.0141.

- 1 2 Appleyard, Rollo (October 1927). "Pioneers of Electrical Communication part 5 - Heinrich Rudolph Hertz" (PDF). Electrical Communication. New York: International Standard Electric Corp. 6 (2): 63–77. Retrieved December 19, 2015.The two images shown are p. 66, fig. 3 and p. 70 fig. 9

- ↑ Heinrich Hertz. nndb.com. Retrieved on 22 August 2014.

- 1 2 Baird, Davis, Hughes, R.I.G. and Nordmann, Alfred eds. (1998). Heinrich Hertz: Classical Physicist, Modern Philosopher. New York: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-7923-4653-X. p. 49

- ↑ Heilbron, John L. (2005) The Oxford Guide to the History of Physics and Astronomy. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195171985. p. 148

- ↑ Baird, Davis, Hughes, R.I.G. and Nordmann, Alfred eds. (1998). Heinrich Hertz: Classical Physicist, Modern Philosopher. New York: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-7923-4653-X. p. 53

- 1 2 Huurdeman, Anton A. (2003) The Worldwide History of Telecommunications. Wiley. ISBN 0471205052. p. 202

- ↑ "The most important Experiments - The most important Experiments and their Publication between 1886 and 1889". Fraunhofer Heinrich Hertz Institute. Retrieved 2016-02-19.

- 1 2 3 4 Pierce, George Washington (1910). Principles of Wireless Telegraphy. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Co. pp. 51–55.

- 1 2 Institute of Chemistry, Hebrew University of Jerusalem: Heinrich Rudolf Hertz.

- ↑ Capri, Anton Z. (2007) Quips, quotes, and quanta: an anecdotal history of physics. World Scientific. ISBN 9812709207. p 93.

- ↑ Norton, Andrew (2000) Dynamic fields and waves. CRC Press. ISBN 0750307196. p. 83.

- ↑ Heinrich Hertz (1893). Electric Waves: Being Researches on the Propagation of Electric Action with Finite Velocity Through Space. Dover Publications. ISBN 1-4297-4036-1.

- ↑ Koertge, Noretta. (2007). Dictionary of Scientific Biography. New York: Thomson-Gale. ISBN 0-684-31320-0. Vol. 6, p. 340.

- ↑ Robertson, Struan II. Buildings Integral to the Former Life and/or Persecution of Jews in Hamburg – Eimsbüttel/Rotherbaum I. uni-hamburg.de

- ↑ Heinrich Rudolf Hertz. Highfields-arc.co.uk. Retrieved on 22 August 2014.

- ↑ L'Harmattan: List of recipients of Japanese Order of the Sacred Treasure (in French)

- ↑ Albanesius, Chloe (22 February 2012). "Google Doodle Honors Heinrich Hertz, Electromagnetic Wave Pioneer". pcmag.com. Retrieved 22 February 2012

- ↑ Heinrich Rudolf Hertz's 155th Birthday. Google (22 February 2012). Retrieved on 22 August 2014.

Further reading

- Hertz, H.R. "Ueber sehr schnelle electrische Schwingungen", Annalen der Physik, vol. 267, no. 7, p. 421–448, May 1887 doi:10.1002/andp.18872670707

- Hertz, H.R. "Ueber einen Einfluss des ultravioletten Lichtes auf die electrische Entladung", Annalen der Physik, vol. 267, no. 8, p. 983–1000, June 1887 doi:10.1002/andp.18872670827

- Hertz, H.R. "Ueber die Einwirkung einer geradlinigen electrischen Schwingung auf eine benachbarte Strombahn", Annalen der Physik, vol. 270, no. 5, p. 155–170, March 1888 doi:10.1002/andp.18882700510

- Hertz, H.R. "Ueber die Ausbreitungsgeschwindigkeit der electrodynamischen Wirkungen", Annalen der Physik, vol. 270, no. 7, p. 551–569, May 1888 doi:10.1002/andp.18882700708

- Hertz, H. R.(1899) The Principles of Mechanics Presented in a New Form, London, Macmillan, with an introduction by Hermann von Helmholtz (English translation of Die Prinzipien der Mechanik in neuem Zusammenhange dargestellt, Leipzig, posthumously published in 1894).

- Jenkins, John D. "The Discovery of Radio Waves – 1888; Heinrich Rudolf Hertz (1847–1894)" (retrieved 27 Jan 2008)

- Naughton, Russell. "Heinrich Rudolph (alt: Rudolf) Hertz, Dr : 1857 – 1894" (retrieved 27 Jan 2008)

- Roberge, Pierre R. "Heinrich Rudolph Hertz, 1857–1894" (retrieved 27 Jan 2008)

- Appleyard, Rollo. (1930). Pioneers of Electrical Communication". London: Macmillan and Company. reprinted by Ayer Company Publishers, Manchester, New Hampshire: ISBN 0-8369-0156-8

- Bodanis, David. (2006). Electric Universe: How Electricity Switched on the Modern World. New York: Three Rivers Press. ISBN 0-307-33598-4

- Buchwald, Jed Z. (1994). The Creation of Scientific Effects: Heinrich Hertz and Electric Waves. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-07887-6

- Bryant, John H. (1988). Heinrich Hertz, the Beginning of Microwaves: Discovery of Electromagnetic Waves and Opening of the Electromagnetic Spectrum by Heinrich Hertz in the Years 1886–1892. New York: IEEE (Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers). ISBN 0-87942-710-8

- Lodge, Oliver Joseph. (1900). Signaling Across Space without Wires by Electric Waves: Being a Description of the work of [Heinrich] Hertz and his Successors. reprinted by Arno Press, New York, 1974. ISBN 0-405-06051-3

- Maugis, Daniel. (2000). Contact, Adhesion and Rupture of Elastic Solids. New York: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 3-540-66113-1

- Susskind, Charles. (1995). Heinrich Hertz: A Short Life. San Francisco: San Francisco Press. ISBN 0-911302-74-3

External links

-

Media related to Heinrich Hertz at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Heinrich Hertz at Wikimedia Commons -

Quotations related to Heinrich Hertz at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Heinrich Hertz at Wikiquote -

"Hertz, Heinrich Rudolf". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

"Hertz, Heinrich Rudolf". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.