Sed festival

The Sed festival (ḥb-sd, conventional pronunciation /sɛd/; also known as Heb Sed or Feast of the Tail) was an ancient Egyptian ceremony that celebrated the continued rule of a pharaoh. The name is taken from the name of an Egyptian wolf god, one of whose names was Wepwawet or Sed.[1]

The less-formal feast name, the Feast of the Tail, is derived from the name of the animal's tail that typically was attached to the back of the pharaoh's garment in the early periods of Egyptian history. This tail might have been the vestige of a previous ceremonial robe made out of a complete animal skin.[2]

Despite the antiquity of the Sed Festival and the hundreds of references to it throughout the history of ancient Egypt, the most detailed records of the ceremonies—apart from the reign of Amenhotep III—come mostly from "relief cycles of the Fifth Dynasty king Neuserra... in his sun temple at Abu Ghurab, of Akhenaten at East Karnak, and the relief cycles of the Twenty-second Dynasty king Osorkon II... at Bubastis."[3]

The ancient festival might, perhaps, have been instituted to replace a ritual of murdering a pharaoh who was unable to continue to rule effectively because of age or condition.[4] Eventually, Sed festivals were jubilees celebrated after a ruler had held the throne for thirty years and then every three (or four in one case) years after that. They primarily were held to rejuvenate the pharaoh's strength and stamina while still sitting on the throne, celebrating the continued success of the pharaoh.

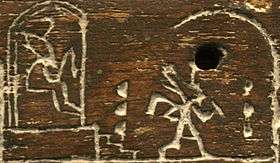

There is clear evidence for early pharaohs celebrating the Heb Sed, such as the First Dynasty pharaoh Den[5] and the Third Dynasty pharaoh Djoser. In the Pyramid of Djoser, there are two boundary stones in his Heb Sed court, which is within his pyramid complex. He also is shown performing the Heb Sed in a false doorway inside his pyramid.

Sed festivals implied elaborate temple rituals and included processions, offerings, and such acts of religious devotion as the ceremonial raising of a djed, the base or sacrum of a bovine spine, a phallic symbol representing the strength, "potency and duration of the pharaoh's rule".[6] One of the earliest Sed festivals for which there is substantial evidence is that of the Sixth Dynasty pharaoh Pepi I Meryre in the South Saqqara Stone Annal document. The most lavish, judging by surviving inscriptions, were those of Ramesses II and Amenhotep III. Sed festivals still were celebrated by the later Libyan-era kings such as Shoshenq III, Shoshenq V, Osorkon I, who had his second Heb Sed in his 33rd year, and Osorkon II, who constructed a massive temple at Bubastis complete with a red granite gateway decorated with scenes of this jubilee to commemorate his own Heb Sed.

Pharaohs who followed the typical tradition, but did not reign so long as 30 years had to be content with promises of "millions of jubilees" in the afterlife.[7]

Several pharaohs seem to have deviated from the traditional 30-year tradition, notably two pharaohs of the Eighteenth Dynasty, Hatshepsut and Akhenaten, rulers in a dynasty that was recovering from occupation by foreigners, reestablishing itself, and redefining many traditions.

Hatshepsut, an extremely successful pharaoh, celebrated her Sed jubilee at Thebes—in what some Victorian-era historians insist was only her sixteenth regnal year—but she did this by counting the time she was the strong consort of her weak husband, and some recent research indicates that she did exercise authority usually reserved for pharaohs during his reign, thereby acting as a co-ruler rather than as his Great Royal Wife, the duties of which were assigned to their royal daughter. Upon her husband's death, the only eligible male in the royal family was a stepson and nephew of hers who was a child. He was made a consort and, shortly thereafter, she was crowned pharaoh. Some Egyptologists, such as Jürgen von Beckerath in his book Chronology of the Egyptian Pharaohs, speculate that Hatshepsut may have celebrated her first Sed jubilee to mark the passing of 30 years from the death of her father, Thutmose I, from whom she derived all of her legitimacy to rule Egypt. He had appointed his daughter to the highest administrative office in his government, giving her a co-regent's experience at ruling many aspects of his bureaucracy. This reflects an oracular assertion supported by the priests of Amun-Re that her father named her as heir to the throne.[8]

Akhenaten made many changes to religious practices in order to remove the stranglehold on the country by the priests of Amun-Re, whom he saw as corrupt. His religious reformation may have begun with his decision to celebrate his first Sed festival in his third regnal year. His purpose may have been to gain an advantage against the powerful temple, since a Sed-festival was a royal jubilee intended to reinforce the pharaoh's divine powers and religious leadership. At the same time he also moved his capital away from the city that these priests controlled.

References

- ↑ Shaw, Ian. Exploring Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press. 2003. ISBN 0-19-511678-X. p. 53

- ↑ Kamil, Jill (1996). The Ancient Egyptians: Life in the Old Kingdom. American Univ in Cairo Press. p. 47. ISBN 978-977-424-392-9.

- ↑ David O'Connor & Eric Cline, Amenhotep: Perspectives on his Reign, University of Michigan, 1998, p. 16.

- ↑ Cottrell, Leonard. The Lost Pharaohs. Evans, 1950. p. 71.

- ↑ Wilkinson, Toby A. H. Early Dynastic Egypt. Routledge, 1999. p. 63. ISBN 0-203-20421-2.

- ↑ Quoted from: Applegate, Melissa Littlefield. The Egyptian Book of Life: Symbolism of Ancient Egyptian Temple and Tomb Art. HCI, 2001. p. 173.

- ↑ William Murnane, The Sed Festival: A Problem in Historical Method, MDAIK 37, pp. 369–76.

- ↑ Breasted, James Henry, Ancient Records of Egypt: Historical Documents from the Earliest Times to the Persian Conquest, The University of Chicago Press, 1907, pp. 116–117.

External links

Media related to Sed festival at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Sed festival at Wikimedia Commons