Heavy-footed moa

| Heavy-footed moa | |

|---|---|

| |

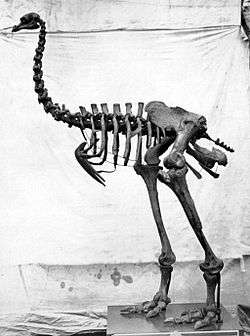

| P. elephantopus skeleton photographed by Roger Fenton | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Superorder: | Paleognathae |

| Order: | Struthioniformes |

| Family: | Dinornithidae |

| Genus: | Pachyornis |

| Species: | Pachyornis elephantopus (Owen, 1856) |

| Binomial name | |

| Pachyornis elephantopus (Owen, 1856) Lydekker 1891 non Cracraft 1976 [1][2] | |

| Synonyms | |

|

List

| |

The heavy-footed moa (Pachyornis elephantopus) is a species of moa from the family Dinornithidae. This moa was widespread on the South Island only, and its habitat was the lowlands (shrublands, dunelands, grasslands, and forests).[3] It was a ratite and a member of the order Struthioniformes. The Struthioniformes are flightless birds with a sternum without a keel. They also have a distinctive palate. The origin of these birds is becoming clearer as it is now believed that early ancestors of these birds were able to fly and flew to the southern areas in which they have been found.[3]

The heavy-footed moa was about 1.8 m (5.9 ft) tall, and weighed as much as 145 kg (320 lb).[4]

Discovery

The heavy-footed moa was discovered by W.B.D. Mantell at Awamoa, near Oamaru, and the bones were taken by him to England. Bones from multiple birds were used to make a full skeleton, which was then put in the British Museum. The name Dinornis elephantopus was given by Richard Owen.[4]

Distribution and habitat

The heavy-footed moa was found only on the South Island of New Zealand.[5][6] Their range covered much of the eastern side of the island, with a northern and southern variant of the species.[5][7]

They were a primarily lowland species, preferring dry and open habitats such as grasslands, shrublands and dry forests.[5] They were absent from sub-alpine and mountain habitats, where they were replaced by the crested moa (Pachyornis australis).[5]

During the Pleistocene-Holocene warming event, the retreat of glacial ice meant that the heavy-footed moa’s preferred habitat area increased, allowing their distribution across the island to increase as well.[7]

Ecology and diet

Due to its relative isolation before the Polynesian settlers arrived, New Zealand has a unique plant and animal community and had no native terrestrial mammals.[6][7] Moa filled the ecological niche of large herbivores, filled by mammals elsewhere, until the arrival of the Polynesian settlers and the associated mammalian invasion in the 13th Century.[7] The heavy-footed Moa is thought to have been less abundant than other moa species due to its less frequent representation in the fossil record.[5]

Until recently it was unknown exactly what the diet of the heavy-footed moa consisted of.[5] The fact that it had different head and beak shapes to its contemporaries suggested that it had a different diet, possibly of tougher vegetation as suggested by its preferred dry and shrubby habitat.[5] Specialising in different foods would have also allowed it to avoid competition with other moa species which may have shared part of its range (niche separation).[5][6] In 2007 Jamie Wood[8] described the gizzard contents of a heavy-footed moa for the first time. They found 21 plant taxa which included Hebe leaves, various seeds and mosses as well as a large amount of twigs and wood, some of which were of a considerable size. This supports the earlier idea that the heavy-footed moa was adapted to consume tough vegetation, but it also shows that it had a varied diet and could eat most plant products, including wood.[8]

The heavy-footed moa’s only real predator (before the arrival of humans and non-native placental mammals) was the Haast's eagle; however, recent evidence from coprolites has shown that they also hosted several groups of host-specific parasites, including nematode worms.[9]

References

- ↑ Brands, S. (2008)

- ↑ Checklist Committee Ornithological Society of New Zealand (2010). "Checklist-of-Birds of New Zealand, Norfolk and Macquarie Islands and the Ross Dependency Antarctica" (PDF). Te Papa Press. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- 1 2 Davies, S. J. J. F. (2003)

- 1 2 Olliver, Narena (2005)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Worthy, T.H. (1990). "An analysis of the distribution and relative abundance of moa species (Aves: Dinornithiformes)". New Zealand Journal of Zoology. 17 (2): 213–241. doi:10.1080/03014223.1990.10422598.

- 1 2 3 Cooper, A., Atkinson, I. A. E., Lee, W. G. & Worthy, T. H. (1993). "Evolution of the moa and their effect on the New Zealand flora". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 8 (12): 433–437. doi:10.1016/0169-5347(93)90005-a.

- 1 2 3 4 Rawlence, N. J., Metcalf, J. L., Wood, J. R. Worthy, T. H., Austin, J. J., & Cooper, A. (2012). "The effect of climate and environmental change on the megafaunal moa of New Zealand in the absence of humans". Quaternary Science Reviews. 50: 141–153. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2012.07.004.

- 1 2 Wood, J. R. (2007). "Moa gizzard content analyses: Further information on the diets of Dinornis robustus and Emeus crassus, and the first evidence for the diet of Pachyornis elephantopus (Aves : Dinornithiformes)". Records of the Canterbury Museum. 21: 27–39.

- ↑ Wood, J. R., Wilmshurst, J. M., Rawlence, N. J., Bonner, K. I., Worthy, T. H., Kinsella, J. M. & Cooper, A. (2013). "A Megafauna's Microfauna: Gastrointestinal Parasites of New Zealand's Extinct Moa (Aves: Dinornithiformes)". PLoS ONE. 8 (2): e57315. PMC 3581471

. PMID 23451203. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0057315.

. PMID 23451203. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0057315.

- Brands, Sheila (Aug 14, 2008). "Systema Naturae 2000 / Classification, Genus Pachyornis". Project: The Taxonomicon. Retrieved Feb 4, 2009.

- Davies, S. J. J. F. (2003). "Moas". In Hutchins, Michael. Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia. 8 Birds I Tinamous and Ratites to Hoatzins (2 ed.). Farmington Hills, MI: Gale Group. pp. 95–98. ISBN 0-7876-5784-0.

- Olliver, Narena (2005). "Heavy–footed Moa". Birds (of New Zealand). New Zealand Birds. Retrieved Feb 15, 2011.

External links

- Heavy-footed Moa. Pachyornis elephantopus. by Paul Martinson. Artwork produced for the book Extinct Birds of New Zealand, by Alan Tennyson, Te Papa Press, Wellington, 2006