Quackery

| This article is part of a series on |

| Alternative and pseudo‑medicine |

|---|

|

|

Fringe medicine and science |

|

Quackery is the promotion[1] of fraudulent or ignorant medical practices. A quack is a "fraudulent or ignorant pretender to medical skill" or "a person who pretends, professionally or publicly, to have skill, knowledge, or qualifications he or she does not possess; a charlatan or snake oil salesman".[2] The term quack is a clipped form of the archaic term quacksalver, from Dutch: kwakzalver a "hawker of salve".[3] In the Middle Ages the term quack meant "shouting". The quacksalvers sold their wares on the market shouting in a loud voice.[4]

Common elements of general quackery include questionable diagnoses using questionable diagnostic tests, as well as untested or refuted treatments, especially for serious diseases such as cancer. Quackery is often described as "health fraud" with the salient characteristic of aggressive promotion.[1]

Definition

Since it is difficult to distinguish between those who knowingly promote unproven medical therapies and those who are mistaken as to their effectiveness, United States courts have ruled in defamation cases that accusing someone of quackery or calling a practitioner a quack is not equivalent to accusing that person of committing medical fraud. To be both quackery and fraud, the quack must know they are misrepresenting the benefits and risks of the medical services offered (instead of, for example, promoting an ineffective product they honestly believe is effective).

In addition to the ethical problems of promising benefits that can not reasonably be expected to occur, quackery also includes the risk that patients may choose to forego treatments that are more likely to help them, in favor of ineffective treatments given by the "quack".[5][6][7]

Stephen Barrett of Quackwatch defines quackery "as the promotion of unsubstantiated methods that lack a scientifically plausible rationale" and more broadly as:

"anything involving overpromotion in the field of health." This definition would include questionable ideas as well as questionable products and services, regardless of the sincerity of their promoters. In line with this definition, the word "fraud" would be reserved only for situations in which deliberate deception is involved.[1]

Paul Offit has proposed four ways in which alternative medicine "becomes quackery":[8]

- "...by recommending against conventional therapies that are helpful."

- "...by promoting potentially harmful therapies without adequate warning."

- "...by draining patients' bank accounts,..."

- "...by promoting magical thinking,..."

Quacksalver

Unproven, usually ineffective, and sometimes dangerous medicines and treatments have been peddled throughout human history. Theatrical performances were sometimes given to enhance the credibility of purported medicines. Grandiose claims were made for what could be humble materials indeed: for example, in the mid-19th century revalenta arabica was advertised as having extraordinary restorative virtues as an empirical diet for invalids; despite its impressive name and many glowing testimonials it was in truth only ordinary lentil flour, sold to the gullible at many times the true cost.

Even where no fraud was intended, quack remedies often contained no effective ingredients whatsoever. Some remedies contained substances such as opium, alcohol and honey, which would have given symptomatic relief but had no curative properties. Some would have addictive qualities to entice the buyer to return. The few effective remedies sold by quacks included emetics, laxatives and diuretics. Some ingredients did have medicinal effects: mercury, silver and arsenic compounds may have helped some infections and infestations; willow bark contained salicylic acid, chemically closely related to aspirin; and the quinine contained in Jesuit's bark was an effective treatment for malaria and other fevers. However, knowledge of appropriate uses and dosages was limited.

Criticism of quackery in academia

The science-based medicine community has criticized the infiltration of alternative medicine into mainstream academic medicine, education, and publications, accusing institutions of "diverting research time, money, and other resources from more fruitful lines of investigation in order to pursue a theory that has no basis in biology."[9][10] R.W. Donnell coined the phrase "quackademic medicine" to describe this attention given to alternative medicine by academia. Referring to the Flexner Report, he said that medical education "needs a good Flexnerian housecleaning."[11]

For example, David Gorski criticized Brian M. Berman, founder of the University of Maryland Center for Integrative Medicine, for writing that "There [is] evidence that both real acupuncture and sham acupuncture [are] more effective than no treatment and that acupuncture can be a useful supplement to other forms of conventional therapy for low back pain." He also castigated editors and peer reviewers at the New England Journal of Medicine for allowing it to be published, since it effectively recommended deliberately misleading patients in order to achieve a known placebo effect.[9][12]

History in Europe and the United States

With little understanding of the causes and mechanisms of illnesses, widely marketed "cures" (as opposed to locally produced and locally used remedies), often referred to as patent medicines, first came to prominence during the 17th and 18th centuries in Britain and the British colonies, including those in North America. Daffy's Elixir and Turlington's Balsam were among the first products that used branding (e.g. using highly distinctive containers) and mass marketing to create and maintain markets.[13] A similar process occurred in other countries of Europe around the same time, for example with the marketing of Eau de Cologne as a cure-all medicine by Johann Maria Farina and his imitators. Patent medicines often contained alcohol or opium, which, while presumably not curing the diseases for which they were sold as a remedy, did make the imbibers feel better and confusedly appreciative of the product.

The number of internationally marketed quack medicines increased in the later 18th century; the majority of them originated in Britain[14] and were exported throughout the British Empire. By 1830, British parliamentary records list over 1,300 different "proprietary medicines,"[15] the majority of which were "quack" cures by modern standards.

A Dutch organisation that opposes quackery, Vereniging tegen de Kwakzalverij (VtdK) was founded in 1881, making it the oldest organisation of this kind in the world.[16] It has published its magazine Nederlands Tijdschrift tegen de Kwakzalverij (Dutch Magazine against Quackery) ever since.[17] In these early years the VtdK played a part in the professionalisation of medicine.[18] Its efforts in the public debate helped to make the Netherlands one of the first countries with governmental drug regulation.[19]

In 1909, in an attempt to stop the sale of quack medicines, the British Medical Association published Secret Remedies, What They Cost And What They Contain.[20][lower-alpha 1] This publication was originally a series of articles published in the British Medical Journal between 1904 and 1909.[22] The publication was composed of 20 chapters, organising the work by sections according to the ailments the medicines claimed to treat. Each remedy was tested thoroughly, the preface stated: "Of the accuracy of the analytical data there can be no question; the investigation has been carried out with great care by a skilled analytical chemist."[20](vi) The book did lead to the end of some of the quack cures, but some survived the book by several decades. For example, Beecham's Pills, which according to the British Medical Association contained in 1909 only aloes, ginger and soap, but claimed to cure 31 medical conditions,[20](p175) were sold until 1998.

British patent medicines lost their dominance in the United States when they were denied access to the Thirteen Colonies markets during the American Revolution, and lost further ground for the same reason during the War of 1812. From the early 19th century "home-grown" American brands started to fill the gap, reaching their peak in the years after the American Civil War.[14][23] British medicines never regained their previous dominance in North America, and the subsequent era of mass marketing of American patent medicines is usually considered to have been a "golden age" of quackery in the United States. This was mirrored by similar growth in marketing of quack medicines elsewhere in the world.

In the United States, false medicines in this era were often denoted by the slang term snake oil, a reference to sales pitches for the false medicines that claimed exotic ingredients provided the supposed benefits. Those who sold them were called "snake oil salesmen," and usually sold their medicines with a fervent pitch similar to a fire and brimstone religious sermon. They often accompanied other theatrical and entertainment productions that traveled as a road show from town to town, leaving quickly before the falseness of their medicine was discovered. Not all quacks were restricted to such small-time businesses however, and a number, especially in the United States, became enormously wealthy through national and international sales of their products.

In 1875, the Pacific Medical and Surgical Journal complained:

If Satan has ever succeeded in compressing a greater amount of concentrated mendacity into one set of human bodies above every other description, it is in the advertising quacks. The coolness and deliberation with which they announce the most glaring falsehoods are really appalling. A recent arrival in San Francisco, whose name might indicate that he had his origin in the Pontine marshes of Europe, announces himself as the "Late examining physician of the Massachusetts Infirmary, Boston." This fellow has the impudence to publish that his charge to physicians in their own cases is $5.00! Another genius in Philadelphia, of the bogus diploma breed, who claims to have founded a new system of practice and who calls himself a "Professor," advertises two elixers of his own make, one of which is for "all male diseases" and the other for "all female diseases"! In the list of preparations which this wretch advertises for sale as the result of his own labors and discoveries, is ozone!

One among many examples is William Radam, a German immigrant to the USA, who, in the 1880s, started to sell his "Microbe Killer" throughout the United States and, soon afterwards, in Britain and throughout the British colonies. His concoction was widely advertised as being able to "cure all diseases",[24] and this phrase was even embossed on the glass bottles the medicine was sold in. In fact, Radam's medicine was a therapeutically useless (and in large quantities actively poisonous) dilute solution of sulfuric acid, coloured with a little red wine.[23] Radam's publicity material, particularly his books,[24] provide an insight into the role that pseudo-science played in the development and marketing of "quack" medicines towards the end of the 19th century.

Similar advertising claims[25] to those of Radam can be found throughout the 18th, 19th, 20th and 21st centuries. "Dr." Sibley, an English patent medicine seller of the late 18th and early 19th centuries, even went so far as to claim that his Reanimating Solar Tincture would, as the name implies, "restore life in the event of sudden death". Another English quack, "Dr. Solomon" claimed that his Cordial Balm of Gilead cured almost anything, but was particularly effective against all venereal complaints, from gonorrhoea to onanism. Although it was basically just brandy flavoured with herbs, the price of a bottle was a half guinea (£sd system) in 1800,[26](p155)[lower-alpha 2] equivalent to over £38 ($51) in 2014.[21]

Not all patent medicines were without merit. Turlingtons Balsam of Life, first marketed in the mid-18th century, did have genuinely beneficial properties. This medicine continued to be sold under the original name into the early 20th century, and can still be found in the British and American Pharmacopoeias as "Compound tincture of benzoin". In these cases, the treatments likely lacked empirical support when they were introduced to the market, and their benefits were simply a convenient coincidence discovered after the fact.

The end of the road for the quack medicines now considered grossly fraudulent in the nations of North America and Europe came in the early 20th century. February 21, 1906 saw the passage into law of the Pure Food and Drug Act in the United States. This was the result of decades of campaigning by both government departments and the medical establishment, supported by a number of publishers and journalists (one of the most effective was Samuel Hopkins Adams, who wrote "The Great American Fraud" series in Collier's in 1905).[27] This American Act was followed three years later by similar legislation in Britain, and in other European nations. Between them, these laws began to remove the more outrageously dangerous contents from patent and proprietary medicines, and to force quack medicine proprietors to stop making some of their more blatantly dishonest claims.

"Medical quackery and promotion of nostrums and worthless drugs were among the most prominent abuses that led to formal self-regulation in business and, in turn, to the creation of the" Better Business Bureau.[28](p1217)

Contemporary culture

"Quackery is the promotion of false and unproven health schemes for a profit. It is rooted in the traditions of the marketplace", with "commercialism overwhelming professionalism in the marketing of alternative medicine".[31] Quackery is most often used to denote the peddling of the "cure-alls" described above. Quackery continues even today; it can be found in any culture and in every medical tradition. Unlike other advertising mediums, rapid advancements in communication through the Internet have opened doors for an unregulated market of quack cures and marketing campaigns rivaling the early 20th century. Most people with an e-mail account have experienced the marketing tactics of spamming—in which modern forms of quackery are touted as miraculous remedies for "weight-loss" and "sexual enhancement", as well as outlets for medicines of unknown quality.

While quackery is often aimed at the aged or chronically ill, it can be aimed at all age groups, including teens, and the FDA has mentioned[32] some areas where potential quackery may be a problem: breast developers, weight loss, steroids and growth hormones, tanning and tanning pills, hair removal and growth, and look-alike drugs.

In 1992, the president of The National Council Against Health Fraud, William T. Jarvis, wrote in Clinical Chemistry that:

The U.S. Congress determined quackery to be the most harmful consumer fraud against elderly people. Americans waste $27 billion annually on questionable health care, exceeding the amount spent on biomedical research. Quackery is characterized by the promotion of false and unproven health schemes for profit and does not necessarily involve imposture, fraud, or greed. The real issues in the war against quackery are the principles, including scientific rationale, encoded into consumer protection laws, primarily the U.S. Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. More such laws are badly needed. Regulators are failing the public by enforcing laws inadequately, applying double standards, and accrediting pseudomedicine. Non-scientific health care (e.g., acupuncture, ayurvedic medicine, chiropractic, homeopathy, naturopathy) is licensed by individual states. Practitioners use unscientific practices and deception on a public who, lacking complex health-care knowledge, must rely upon the trustworthiness of providers. Quackery not only harms people, it undermines the scientific enterprise and should be actively opposed by every scientist.[33]

For those in the practice of any medicine, to allege quackery is to level a serious objection to a particular form of practice. Most developed countries have a governmental agency, such as the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the US, whose purpose is to monitor and regulate the safety of medications as well as the claims made by the manufacturers of new and existing products, including drugs and nutritional supplements or vitamins. The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) participates in some of these efforts.[34] To better address less regulated products, in 2000, US President Clinton signed Executive Order 13147 that created the White House Commission on Complementary and Alternative Medicine. In 2002, the commission's final report made several suggestions regarding education, research, implementation, and reimbursement as ways to evaluate the risks and benefits of each.[35] As a direct result, more public dollars have been allocated for research into some of these methods.

Individuals and non-governmental agencies are active in attempts to expose quackery. According to John C. Norcross et al. less is consensus about ineffective "compared to effective procedures" but identifying both "pseudoscientific, unvalidated, or 'quack' psychotherapies" and "assessment measures of questionable validity on psycho-metric grounds" was pursued by various authors.[36](p515) The evidence-based practice (EBP) movement in mental health emphasizes the consensus in psychology that psychological practice should rely on empirical research.[36](pp515, 522) There are also "anti-quackery" websites, such as Quackwatch, that help consumers evaluate claims.[37] Quackwatch's information is relevant to both consumers and medical professionals.[38]

People's Republic of China

Zhang Wuben, a quack who posed as skilled in traditional Chinese medicine in the People's Republic of China, based his operation on representations that raw eggplant and mung beans were a general cure-all. Zhang, who has escaped legal liability as he portrayed himself as a nutritionist, not a doctor, appeared on television in China and authored a best-selling book, Eat Away the Diseases You Get from Eating. Zhang, who charged the equivalent of $450 for a 10-minute examination, had a two-year waiting list when he was exposed. Investigations launched after a run on mung beans revealed that contrary to his representations, he did not come from a family of accomplished traditional practitioners (中医世家) and never had the medical degree from Beijing Medical University he claimed to have. His only education was a brief correspondence or night school course, completed after he was laid off from a textile factory. Zhang, despite negative publicity on the national level, continues to practice but has committed himself to finding a cheaper cure-all than mung beans. His clinic, Wuben Hall, adjacent to Beijing National Stadium, was torn down as an illegal structure. Much of Zhang Wuben's success was due to the efforts of Chinese entrepreneurs, including one government-owned company, who promoted him.[39][40][41]

Hu Wanlin, who did hold himself out as a doctor, was exposed in 2000 and sentenced to 15 years in prison. He adulterated his concoctions with sodium sulfate, Glauber's salt, a poison in large doses. That case resulted in creating a system of licensing medical doctors in China.[41]

Presence and acceptance

There have been several suggested reasons why quackery is accepted by patients in spite of its lack of effectiveness:

- Ignorance

- Those who perpetuate quackery may do so to take advantage of ignorance about conventional medical treatments versus alternative treatments, or may themselves be ignorant regarding their own claims. Mainstream medicine has produced many remarkable advances, so people may tend to also believe groundless claims.

- Medicines or treatments known to have no pharmacological effect on a disease can still affect a person's perception of their illness, and this belief in its turn does indeed sometimes have a therapeutic effect, causing the patient's condition to improve. This is not to say that no real cure of biological illness is effected – "though we might describe a placebo effect as being 'all in the mind', we now know that there is a genuine neurobiological basis to this phenomenon."[42] People report reduced pain, increased well-being, improvement, or even total alleviation of symptoms. For some, the presence of a caring practitioner and the dispensation of medicine is curative in itself.

- Lack of understanding that health conditions change with no treatment and attributing changes in ailments to a given therapy.[43]

- Also called myside bias, is the tendency to search for, interpret, or prioritize information in a way that confirms one's beliefs or hypotheses. It is a type of cognitive bias and a systematic error of inductive reasoning.

- Distrust of conventional medicine

- Many people, for various reasons, have a distrust of conventional medicine, or of the regulating organizations such as the FDA, or the major drug corporations. For example, "CAM may represent a response to disenfranchisement [discrimination] in conventional medical settings and resulting distrust".[44]

- Anti-quackery activists ("quackbusters") are accused of being part of a huge "conspiracy" to suppress "unconventional" and/or "natural" therapies, as well as those who promote them. It is alleged that this conspiracy is backed and funded by the pharmaceutical industry and the established medical care system – represented by the AMA, FDA, ADA, CDC, WHO, etc. – for the purpose of preserving their power and increasing their profits. In the case of chiropractic, the case for a conspiracy was supported by a court decision in an antitrust lawsuit, Wilk v. American Medical Association, ruling that the AMA had engaged in an unlawful conspiracy in restraint of trade "to contain and eliminate the chiropractic profession."[45][46][47]

- Fear of side effects

- A great variety of pharmaceutical medications can have very distressing side effects, and many people fear surgery and its consequences, so they may opt to shy away from these mainstream treatments.

- Cost

- There are some people who simply cannot afford conventional treatment, and seek out a cheaper alternative. Nonconventional practitioners can often dispense treatment at a much lower cost. This is compounded by reduced access to healthcare.

- Desperation

- People with a serious or terminal disease, or who have been told by their practitioner that their condition is "untreatable," may react by seeking out treatment, disregarding the lack of scientific proof for its effectiveness, or even the existence of evidence that the method is ineffective or even dangerous. Despair may be exacerbated by the lack of palliative non-curative end-of-life care.

- Pride

- Once people have endorsed or defended a cure, or invested time and money in it, they may be reluctant or embarrassed to admit its ineffectiveness and therefore recommend a treatment that does not work.

- Fraud

- Some practitioners, fully aware of the ineffectiveness of their medicine, may intentionally produce fraudulent scientific studies and medical test results, thereby confusing any potential consumers as to the effectiveness of the medical treatment.

Persons accused of quackery

Deceased

- Thomas Allinson (1858–1918), founder of naturopathy. His views often brought him into conflict with the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh and the General Medical Council, particularly his opposition to doctors' frequent use of drugs, his opposition to vaccination and his self-promotion in the press.[48] His views and publication of them led to him being labeled a quack and being struck off by the General Medical Council for infamous conduct in a professional respect.[49][50]

- Lovisa Åhrberg (1801–1881), the first Swedish female doctor. Åhrberg was met with strong resistance from male doctors and was accused of quackery. During the formal examination she was acquitted of all charges and allowed to practice medicine in Stockholm even though it was forbidden for women in the 1820s. She later received a medal for her work.

- Johanna Brandt (1876–1964), a South African naturopath who advocated the "Grape Cure" as a cure for cancer.[51]

- John R. Brinkley (1885–1942), a Kansas nonphysician and xenotransplant specialist who claimed to have discovered a method of effectively transplanting the testicles of goats into aging men. After state authorities took steps to shut down his practice, he retaliated by entering politics in 1930 and running for the office of Governor of Kansas.[52]

- Hulda Regehr Clark (1928–2009), was a controversial naturopath, author, and practitioner of alternative medicine who claimed to be able to cure all diseases and advocated methods that have no scientific validity.[53]

- Max Gerson (1881–1959), was a German-born American physician who developed a dietary-based alternative cancer treatment that he claimed could cure cancer and most chronic, degenerative diseases. His treatment was called The Gerson Therapy. Most notably, Gerson Therapy was used, unsuccessfully, to treat Jessica Ainscough. According to Quackwatch, Gerson Institute claims of cure are based not on actual documentation of survival, but on "a combination of the doctor's estimate that the departing patient has a 'reasonable chance of surviving', plus feelings that the Institute staff have about the status of people who call in".[54] The American Cancer Society reports that "[t]here is no reliable scientific evidence that Gerson therapy is effective..."[55]

- Samuel Hahnemann (1755–1843), founder of homeopathy. Hahnemann believed that all diseases were caused by "miasms," which he defined as irregularities in the patient's vital force.[56] He also said that illnesses could be treated by substances that in a healthy person produced similar symptoms to the illness, in extremely low concentrations, with the therapeutic effect increasing with dilution and repeated shaking.[57][58][59]

- Lawrence B. Hamlin (in 1916), was fined under the 1906 Pure Food and Drug Act for advertising that his Wizard Oil could kill cancer.[60]

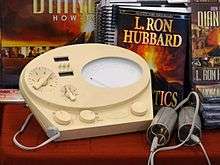

- L. Ron Hubbard (1911–1986), was the founder of the Church of Scientology. He was an American science fiction writer, former United States Navy officer, and creator of Dianetics. He has been commonly called a quack and a conman by both critics of Scientology and by many psychiatric organizations in part for his often extreme anti-psychiatric beliefs.[61][62][63]

- William Donald Kelley, (1925–2005), was an orthodontist and a follower of Max Gerson who developed his own alternative cancer treatment called Nonspecific Metabolic Therapy. This treatment is based on the unsubstantiated belief that "wrong foods [cause] malignancy to grow, while proper foods [allow] natural body defenses to work".[64] It involves, specifically, treatment with pancreatic enzymes, 50 daily vitamins and minerals (including laetrile), frequent body shampoos, coffee enemas, and a specific diet.[65] According to Quackwatch, "not only is his therapy ineffective,[66] but people with cancer who take it die more quickly and have a worse quality of life than those having standard treatment, and can suffer serious or fatal side-effects. Kelley's most famous patient was actor Steve McQueen.

- John Harvey Kellogg (1852–1943), was a medical doctor in Battle Creek, Michigan, USA who ran a sanitarium using holistic methods, with a particular focus on nutrition, enemas and exercise. Kellogg was an advocate of vegetarianism and invented the corn flake breakfast cereal with his brother, Will Keith Kellogg.[67]

- John St. John Long (1798–1834) was an Irish artist who claimed to be able to cure tuberculosis by causing a sore or wound on the back of the patient, out of which the disease would exit. He was tried twice for manslaughter of his patients who died under this treatment.[68]

- Franz Anton Mesmer (1734–1815), was a German physician and astrologist, who invented what he called magnétisme animal.

- Theodor Morell (1886–1948), a German physician best known as Adolf Hitler's personal doctor. Morell administered approximately 74 substances (in 28 different mixtures)[69] to Hitler, including heroin, cocaine, Doktor Koster's Antigaspills, potassium bromide, papaverine, testosterone, vitamins and animal enzymes.[70] Despite Hitler's dependence on Morell, and his recommendations of him to other Nazi leaders, Hermann Göring, Heinrich Himmler, Albert Speer and others quietly dismissed Morell as a quack.

- Daniel David Palmer (1845–1913), was a grocery store owner that claimed to have healed a janitor of deafness after adjusting the alignment of his back. He founded the field of chiropractic based on the principle that all disease and ailments could be fixed by adjusting the alignment of someone's back. His hypothesis was disregarded by medical professionals at the time and despite a considerable following has yet to be scientifically proven.[71] Palmer established a magnetic healing facility in Davenport, Iowa, styling himself 'doctor'. Not everyone was convinced, as a local paper in 1894 wrote about him: "A crank on magnetism has a crazy notion that he can cure the sick and crippled with his magnetic hands. His victims are the weak-minded, ignorant and superstitious, those foolish people who have been sick for years and have become tired of the regular physician and want health by the short-cut method…he has certainly profited by the ignorance of his victims…His increase in business shows what can be done in Davenport, even by a quack."[72]

- Louis Pasteur (1822–1895), was a French chemist best known for his remarkable breakthroughs in microbiology. His experiments confirmed the germ theory of disease, also reducing mortality from puerperal fever (childbed), and he created the first vaccine for rabies. He is best known to the general public for showing how to stop milk and wine from going sour – this process came to be called pasteurization. His hypotheses initially met with much hostility, and he was accused of quackery on multiple occasions. However, he is now regarded as one of the three main founders of microbiology, together with Ferdinand Cohn and Robert Koch.[73]

- Linus Pauling (1901–1994), a Nobel Prize winner in chemistry, Pauling spent much of his later career arguing for the treatment of somatic and psychological diseases with orthomolecular medicine. Among his claims were that the common cold could be cured with massive doses of vitamin C. Together with Ewan Cameron he wrote the 1979 book "Cancer and Vitamin C", which was again more popular with the public than the medical profession, which continued to regard claims about the effectiveness of vitamin C in treating or preventing cancer as quackery.[74] A biographer has discussed how controversial his views on megadoses of Vitamin C have been and that he was "still being called a 'fraud' and a 'quack' by opponents of his 'orthomolecular medicine'".[75]

- Doctor John Henry Pinkard (1866–1934) was a Roanoke, Virginia businessman and "Yarb Doctor" or "Herb Doctor" who concocted quack medicines that he sold and distributed in violation of the Food and Drugs Act and the earlier Pure Food and Drug Act. He was also known as a "...clairvoyant, herb doctor and spiritualist."[76] Some of Pinkard's Sanguinaria Compound, made from bloodroot or bloodwort, was seized by federal officials in 1931. "Analysis by this department of a sample of the article showed that it consisted essentially of extracts of plant drugs including sanguinaria, sugar, alcohol, and water. It was alleged in the information that the article was misbranded in that certain statements, designs, and devices regarding the therapeutic and curative effects of the article, appearing on the bottle label, falsely and fraudulently represented that it would be effective as a treatment, remedy, and cure for pneumonia, coughs, weak lungs, asthma, kidney, liver, bladder, or any stomach troubles, and effective as a great blood and nerve tonic." He pleaded guilty and was fined.[77]

- Wilhelm Reich (1897–1957), Austrian-American Psychoanalyst. Claimed that he had discovered a primordial cosmic energy called Orgone. He developed several devices, including the Cloudbuster and the Orgone Accumulator, that he believed could use orgone to manipulate the weather, battle space aliens and cure diseases, including cancer. After an investigation, the FDA concluded that they were dealing with a "fraud of the first magnitude". On February 10, 1954, the U.S. Attorney for Maine filed a complaint seeking a permanent injunction under Sections 301 and 302 of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, to prevent interstate shipment of orgone accumulators and to ban some of Reich's writing promoting and advertising the devices. Reich refused to appear in court, arguing that no court was in a position to evaluate his work. Reich was arrested for contempt of court, and convicted to 2 years in jail, a $10,000 fine, and his Orgone Accumulators and work on Orgone were ordered destroyed. On August 23, 1956, six tons of his books, journals, and papers were burned in the 25th Street public incinerator in New York. On March 12, 1957 he was sent to Danbury Federal Prison, where Richard C. Hubbard, a psychiatrist who admired Reich, examined him, recording paranoia manifested by delusions of grandiosity, persecution, and ideas of reference. On November 18, 1957 Reich died of a heart attack 9 months later while he was in the federal penitentiary in Lewisburg, Pennsylvania.

- William Herbert Sheldon (1898–1977), who created the theory of somatotypes corresponding to intelligence.[78][79]

Living

- Stanislaw Burzynski conducts experimental research on and administers antineoplastons to cancer patients, which are ineffective and dangerous.[80] Burzynski operates the Burzynski Clinic in Houston, Texas. He has been involved in numerous lawsuits and the subject of FDA warnings.[81] Aided through aggressive legal threats to critics and an active group of patient-supporters, Burzynski continues practicing cancer quackery.[82][83]

- Ann Louise Gittleman (born 1949) published a series of fad diet books that promote pseudoscientific ideas about weight loss,[84][85] "detoxification",[86] and electromagnetic radiation.[87][88] She received a PhD from the now defunct Clayton College of Natural Health,[87] which is known as a diploma mill that gave degrees to a number of individuals who went on to be accused of quackery.[89]

- Mehmet Oz (born 1960), as host of The Dr. Oz Show, has promoted pseudoscientific health treatments and supplements, and faced a hearing at the United States Senate for helping companies sell fraudulent medicine.[90][91][92]

- Kevin Trudeau (born 1963) published several books about cures relating to maladies, weight loss, and debt. He is currently in an Alabaman jail for failing to pay a $37.6 million fine that he incurred as a result of claims he made in his book about weight loss cures.[93][94][95]

- Andrew Wakefield (born 1957) published a fraudulent study in The Lancet in 1998 claiming that the MMR vaccine increases the chance of autism. His research has been described as "an elaborate fraud". None of his results could be reproduced by other researchers. The study claimed the combined MMR vaccine increased the risk of autism, while Wakefield had just applied for patent on separate vaccines for the three diseases, and therefore the study, if accepted, would have generated a large profit for Wakefield.[96][97][98][99] The General Medical Council subsequently struck Wakefield off its register.

- Tullio Simoncini (born 1951)

See also

- Alternative cancer treatments

- Alternative medicine

- Confidence trick

- Consumer protection

- Crystal healing

- Fraud

- Health care fraud

- List of topics characterized as pseudoscience

- Medical ethics

- Medical error

- Naturopathy

- Psychic

- Radioactive quackery

Regulatory organizations

- Federal Trade Commission

- Food and Drug Administration

- Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency

Anti-quackery organizations

Notes

- ↑ The British Medical Association estimated that, based on ad valorem tax revenues from patent medicines for the fiscal year ending March 31, 1908, the British public spent about £2.42 million on patent medicines.[20](pp182–84) This is equivalent to about £226 million ($305 million) in 2014.[21]

- ↑ The price of a bottle of Cordial Balm of Gilead was 33 shillings in the period of the Napoleonic wars, equivalent to over £109 ($147) in 2014.[21]

References

- 1 2 3 Barrett, Stephen (2009-01-17). "Quackery: how should it be defined?". quackwatch.org. Archived from the original on 2009-02-25. Retrieved 2013-08-09.

- ↑ "quack". Dictionary.com Unabridged. Random House. Retrieved 2007-02-07.

- ↑ Harper, Douglas. "quack". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 2015-11-06.

- ↑ "German-English glossary of idioms". accurapid.com. Poughkeepsie, New York: Accurapid. quacksalber. Archived from the original on 2010-12-04.

- ↑ Tabish, Syed Amin (January 2008). "Complementary and alternative healthcare: is it evidence-based?". International Journal of Health Sciences. Qassim, SA: Qassim University. 2 (1): v–ix. ISSN 1658-3639. PMC 3068720

. PMID 21475465.

. PMID 21475465. - ↑ Angell, Marcia; Kassirer, Jerome P. (17 September 1998). "Alternative Medicine – The Risks of Untested and Unregulated Remedies". New England Journal of Medicine. 339 (12): 839–41. PMID 9738094. doi:10.1056/NEJM199809173391210.

- ↑ Cassileth, Barrie R.; Yarett, I.R. (2012). "Cancer quackery: the persistent popularity of useless, irrational 'alternative' treatments.". Oncology. 28 (8): 754–58.

- ↑ Offit, Paul A. (2013). Do you believe in magic? : the sense and nonsense of alternative medicine. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 9780062222961. Also titled Killing us softly: the sense and nonsense of alternative medicine. London: Fourth Estate. 2013. ISBN 9780007491728.

- 1 2 Gorski, David (2010-08-03). "Credulity about acupuncture infiltrates the New England Journal of Medicine ". sciencebasedmedicine.org. Science-Based Medicine. Archived from the original on 2010-12-10.

- ↑ Novella, Steven (2010-08-04). "Acupuncture pseudoscience in the New England Journal of Medicine ". sciencebasedmedicine.org. Science-Based Medicine. Archived from the original on 2010-08-07.

- ↑ Donnell, Robert W. "Exposing quackery in medical education". doctorrw.blogspot.com (blog). Archived from the original on 2008-02-05.

- ↑ Berman, Brian M.; Langevin, Helene M.; Witt, Claudia M.; Dubner, Ronald (2010-07-29). "Acupuncture for chronic low back pain". New England Journal of Medicine. 363 (5): 454–61. PMID 20818865. doi:10.1056/NEJMct0806114. Correction of an author name in "Acupuncture for chronic low back pain". New England Journal of Medicine. 363 (9): 893. 2010-08-26. doi:10.1056/NEJMx100048.

- ↑ Styles, John (2000). "Product innovation in early modern London". Past & Present. Oxford University Press. 168 (1): 124–69. doi:10.1093/past/168.1.124.

- 1 2 Griffenhagen, George B.; Young, James Harvey (1959) [first published in 1929]. Old English patent medicines in America. Contributions from the museum of history and technology. 10. [Washington, DC]: [Smithsonian Institution] (published 2009). pp. 155–83. OCLC 746980411. Project Gutenberg, 30162 – via Project Gutenberg.

- ↑ "House of Commons Journal, 8 April 1830". British-history.ac.uk. 2003-06-22. Retrieved 2013-08-09.

- ↑ Lewis, Andy (3 August 2009). "Dutch sceptics have 'bogus' libel decision overturned on human rights grounds". quackometer.net (blog). Andy Lewis. Archived from the original on 2014-02-13. Retrieved 2014-05-16.

- ↑ De Kort, Marcel (1995). Tussen patient en delinquent: geschiedenis van het Nederlandse drugsbeleid [Between patient and delinquent: the history of drug policy in the Netherlands]. Publikaties van de Faculteit der Historische en Kunstwetenschappen (in Dutch). 19. Hilversum: Verloren. pp. 25–26. ISBN 9789065504203.

- ↑ De Kort, Marcel (1993). "Drug policy: medical or crime control? Medicalization and criminalization of drug use, and shifting drug policies". In Binneveld, Hans. Curing and insuring: essays on illness in past times: the Netherlands, Belgium, England and Italy, 16th–20th centuries. Illness and History, Rotterdam, 16 November 1990. Publikaties van de Faculteit der Historische en Kunstwetenschappen. 9. Hilversum: Verloren. pp. 207–08. ISBN 9789065504081.

- ↑ Oudshoorn, Nelly (1993). "United we stand: the pharmaceutical industry, laboratory, and clinic in the development of sex hormones into scientific drugs, 1920–1940". Science, Technology & Human Values. Sage Publications. 18 (1): 5–24. JSTOR 689698. doi:10.1177/016224399301800102.

- 1 2 3 4 British Medical Journal (1909). Secret remedies, what they cost and what they contain. London: British medical association. OCLC 807108391.

- 1 2 3 UK Consumer Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Gregory Clark (2016), "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)", MeasuringWorth.com.

- ↑ "The Composition of Certain Secret Remedies: I.-Some Remedies for Epilepsy.". British Journal of Medicine. 2 (2293): 1585–86. Dec 10, 1904. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.2293.1585.

- 1 2 Young, James H. (1961). The toadstool millionaires: a social history of patent medicines in America before federal regulation. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. OCLC 599159278. Archived from the original on 2002-10-10 – via quackwatch.org.

- 1 2 Radam, William (1895) [1890]. Microbes and the microbe killer (Rev. ed.). New York: The author. pp. 137, 180, 205. OCLC 768310771.

I offer to cure all diseases with but one remedy, and to stop children dying of disease, for of course I cannot prevent accidents in all cases that are taken in time, and where my instructions are faithfully followed.

- ↑ Clark, Hulda Regehr (1995). The cure for all diseases: with many case histories of diabetes, high blood pressure, seizures, chronic fatigue syndrome, migraines, Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, multiple sclerosis, and others showing that all of these can be simply investigated and cured. San Diego, CA: ProMotion. ISBN 9781890035013.

- ↑ Helfand, William H. (1989). "President's address: Samuel Solomon and the Cordial Balm of Gilead". Pharmacy in History. Madison, WI: American Institute of the History of Pharmacy. 31 (4): 151–59. ISSN 0031-7047. JSTOR 41111251.

- ↑ Adams, Samuel Hopkins (1912) [1905]. The great American fraud: articles on the nostrum evil and quackery reprinted from Collier's (5th ed.). Chicago: American Medical Association. OCLC 894099555.

- ↑ Ladimer, Irving (August 1965). "The Health Advertising Program of the National Better Business Bureau". American Journal of Public Health. 55 (8): 1217–27. PMC 1256406

. PMID 14326419. doi:10.2105/ajph.55.8.1217.

. PMID 14326419. doi:10.2105/ajph.55.8.1217. - ↑ "Religion's Shocking Experience". St Petersburg Times. 3 May 1969. Retrieved 27 September 2012.

- ↑ Janssen, Wallace (1993). "The gadgeteers". In Barrett, Stephen; Jarvis, William. The health robbers: a close look at quackery in America. Consumer health library. Buffalo, NY: Prometheus Books. ISBN 9780879758554.

- ↑ Jarvis WT (November 1999). "Quackery: the National Council Against Health Fraud perspective". Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 25 (4): 805–14. PMID 10573757. doi:10.1016/S0889-857X(05)70101-0.

- ↑ Food and Drug Administration; Council of Better Business Bureaus (April 1990) [February 1988]. "Quackery targets teens". cfsan.fda.gov. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services. Public Health Service. Food and Drug Administration. DHHS Publication No. (FDA) 90-1147. Archived from the original on 2009-05-12.

- ↑ Jarvis, WT (August 1992). "Quackery: a national scandal". Clinical Chemistry. 38 (8B Pt 2): 1574–86. ISSN 0009-9147. PMID 1643742.

- ↑ ""Operation Cure.all" Targets Internet Health Fraud". Federal Trade Commission. June 24, 1999.

- ↑ White House Commission on Complementary and Alternative Medicine Policy (March 2002). Final report (PDF). NIH publication. 03-5411. Washington, DC: United States. Department of Health and Human Services. ISBN 9780160514760. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2004-10-16.

- 1 2 Norcross, John C.; Koocher, Gerald P.; Garofalo, Ariele (Oct 2006). "Discredited psychological treatments and tests: a Delphi poll". Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. American Psychological Association. 37 (5): 515–22. doi:10.1037/0735-7028.37.5.515.

- ↑ Baldwin, Fred D. (2004-07-19). "If it quacks like a duck...". medhunters.com. [s.l.]: MedHunters. Archived from the original on 2008-02-06. Retrieved 2007-10-13.

- ↑ Nguyen-Khoa, Bao-Anh (July 1999). "Selected Web Site Reviews – Quackwatch.com". The Consultant Pharmacist. Archived from the original on December 14, 2007. Retrieved 2007-01-25.

- ↑ Jacobs, Andrew; et al. (2010-10-07) [2010-10-06]. "Rampant fraud threat to China's brisk ascent". www.nytimes.com. New York: The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-10-07.

- ↑ Mu, Eric (2010-06-18). "Zhang Wuben and the traditional Chinese medicine racket". danwei.org. Archived from the original on 2010-06-21. Retrieved 2010-10-07.

- 1 2 Shengxia, Song; et al. (2010-05-31). "Popular diet guru exposed as fraud". china.globaltimes.cn. Global Times. Archived from the original on 2010-06-04. Retrieved 2010-10-07.

- ↑ Benedetti, Fabrizio. Placebo effects: understanding the mechanisms in health and disease. Oxford University Press 2009. back cover. ISBN 978-0-19-955912-1.

- ↑ J. Thomas Butler (1 July 2011). Consumer Health: Making Informed Decisions. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. pp. 64–. ISBN 978-0-7637-9340-1.

- ↑ Shippee, Tetyana; Henning-Smith, Carrie; Shippee, Nathan; Kemmick Pintor, Jessie; Call, Kathleen T.; McAlpine, Donna; Johnson, Pamela Jo (2013). "Discrimination in Medical Settings and Attitudes toward Complementary and Alternative Medicine: The Role of Distrust in Conventional Providers". Journal of Health Disparities Research and Practice. 6 (1): 3.

- ↑ Johnson C, Baird R, Dougherty PE, et al. (2008). "Chiropractic and public health: current state and future vision". J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 31 (6): 397–410. PMID 18722194. doi:10.1016/j.jmpt.2008.07.001.

- ↑ Cherkin D (1989). "AMA policy on chiropractic". Am J Public Health. 79 (11): 1569–70. PMC 1349822

. PMID 2817179. doi:10.2105/AJPH.79.11.1569-a.

. PMID 2817179. doi:10.2105/AJPH.79.11.1569-a. - ↑ Cooper RA, McKee HJ (2003). "Chiropractic in the United States: trends and issues". Milbank Q. 81 (1): 107–38. PMC 2690192

. PMID 12669653. doi:10.1111/1468-0009.00040.

. PMID 12669653. doi:10.1111/1468-0009.00040. - ↑ Scott CJ (1999). "The Life and Trials of TR Allinson ex L.R.C.P.ED 1858–1918". Proc. R. Coll. Physicians Edinb. 29 (3): 258–61. PMID 11624001.

- ↑ "Diet advice 1893 style lost doctor his job". Daily Express. 2 January 2008.

- ↑ Janet Smith (27 January 2005). "The Shipman Inquiry". Department of Health.

- ↑ Barrett, Stephen (2001-09-18). "The grape cure". quackwatch.org. Archived from the original on 2002-10-01.

- ↑ Hutchens, John K. (June 7, 1942). "Notes on the Late Dr. John R. Brinkley, Whom Radio Raised to a Certain Fame". New York Times. Retrieved 2009-05-07.

- ↑ Barrett, Stephen (2009-10-23). "The bizarre claims of Hulda Clark". quackwatch.org. Archived from the original on 2009-12-10.

- ↑ Lowell, James (February 1986). "Background History of the Gerson Clinic". Nutrition Forum Newsletter. Quackwatch. Retrieved April 22, 2009.

- ↑ "Gerson Therapy". American Cancer Society. Retrieved April 22, 2009.

- ↑ Samuel Hahnemann. Organon of Medicine (5th ed.). para 29.

- ↑ "The Life and Letters of Dr Samuel Hahnemann". Retrieved 24 December 2007.Template:Rs-inline

- ↑ Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr. (1842). "Homoeópathy and its kindred delusions: Two lectures delivered before the Boston Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge". Boston., reprinted in Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr. (1861). Currents and Counter-currents in Medical Science. Ticknor and Fields. pp. 72–188.

- ↑ Michael Emmans Dean (2001). "Homeopathy and the "Progress of Science" (PDF). Hist. Sci. xxxix (125 Pt 3): 255–83. Bibcode:2001HisSc..39..255E. PMID 11712570.

- ↑ E.C. Alft. "Chapter 7: Good Old Days". Elgin: Days Gone By. Elgin History. Retrieved 2009-09-25.

- ↑ "Operation Clambake presents: FBI Files on L Ron Hubbard". xenu.net.

- ↑ Virginia Linn (July 24, 2005). "L. Ron Hubbard". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

- ↑ David S. Touretzky. "Secrets of Scientology: The E-Meter". Computer Science Department & Center for the Neural Basis of Cognition, Carnegie Mellon University.

- ↑ Lerner BH (2006). Chapter 7: Unconventional Healing – Steve McQueen's Mexican Journey. When Illness Goes Public: Celebrity Patients and How We Look at Medicine. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press. pp. 139–. ISBN 0-8018-8462-4.

- ↑ Lerner, Barron H. (15 November 2005). "McQueen's Legacy of Laetrile". New York Times. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- ↑ Green S (20 April 2000). "Nicholas Gonzalez Treatment for Cancer: Gland Extracts, Coffee Enemas, Vitamin Megadoses, and Diets". Quackwatch. Retrieved February 2014. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ "John Harvey Kellogg". Museum of Quackery.

- ↑ Hempel, Sandra (May 3, 2014). "John St John Long: quackery and manslaughter". The Lancet. 383 (9928): 1540–41. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60737-6.

- ↑ Trevor-Roper, Hugh (2012). "The Last Days of Hitler". Pan Macmillan. pp. 79–82. ISBN 0330470272. Retrieved 8 September 2015 – via Google Books, preview.

- ↑ Hitler's Hidden Drug Habit: Secret History on YouTube directed and produced by Chris Durlacher. A Waddell Media Production for Channel 4 in association with National Geographic Channels, MMXIV. Executive Producer Jon-Barrie Waddell.

- ↑ Cleveland, Carl (July 1952). "History of Chiropractic".

- ↑ Colquhoun, D (July 2008). "Doctor Who? Inappropriate use of titles by some alternative "medicine" practitioners". The New Zealand medical journal. 121 (1278): 6–10. ISSN 0028-8446. PMID 18670469. Archived from the original on June 15, 2009.

- ↑ John W. Campbell, Jr., ed. (June 1964). Louis Pasteur, Medical Quack. Analog.

- ↑ Dunitz, Jack D. (November 1996). "Linus Carl Pauling, 28 February 1901–19 August 1994". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 42: 316–338. PMID 11619334. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1996.0020.

- ↑ Thomas Blair. Linus Pauling: Nobel Laureate for Peace and Chemistry 1901–1994 Archived January 10, 2010, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Margaret Claytor Woodbury and Ruth Claytor Marsh. Virginia Kaleidoscope: the Claytor family of Roanoke, and some of its kinships, from first families of Virginia and their former slaves. M.C. Woodbury, 1994. p. 408. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/34546014

- ↑ Case #19890. Misbranding of Pinkard's sanguinaria compound. U. S. v. John Henry Pinkard. Plea of guilty. Fine, $25.

- ↑ "Nude Photos Are Sealed At Smithsonian". New York Times. January 21, 1995. Retrieved December 1, 2011.

Later, other photographs were taken by W. H. Sheldon, a researcher who believed that there was a relationship between body shape and intelligence and other traits. Mr. Sheldon has since died, and his work has long been dismissed by most scientists as quackery. ...

- ↑ "Nude Photos of Yale Graduates Are Shredded". New York Times. January 29, 1995. Retrieved 2011-12-07.

Mr. Sheldon, whose work has since been dismissed by most scientists, died in 1977. ...

- ↑ Vickers, Andrew (2004). "Alternative cancer cures: 'unproven' or 'disproven'?". CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 54 (2): 110–18. PMID 15061600. doi:10.3322/canjclin.54.2.110.

- ↑ Gorski, David (2014). "Stanislaw Burzynski: four decades of an unproven cancer cure". Skeptical inquirer. Committee for Skeptical Inquiry. 38 (2): 36. ISSN 0194-6730. Archived from the original on 2014-04-06.

- ↑ Blaskiewicz, Robert (2014). "Skeptic activists fighting for Burzynski's cancer patients". Skeptical inquirer. Committee for Skeptical Inquiry. 38 (2): 44–47. ISSN 0194-6730. Archived from the original on 2014-04-07.

- ↑ McCartney, Margaret (2011). "Texan clinic threatens UK bloggers with legal action over criticisms of its treatments". BMJ. 343: d7865. PMID 22138837. doi:10.1136/bmj.d7865.

- ↑ Maureen Callahan. "Fat Flush - Diet Fitness". Health.com. Retrieved 2016-03-02.

- ↑ "The Fat Flush Diet". Healthline. 11 February 2016. Retrieved 28 April 2017.

- ↑ Elin, Abby (21 January 2009). "Flush Those Toxins! Eh, Not So Fast". New York Times. Retrieved 4 March 2016.

- 1 2 Poppy, Carrie (1 February 2016). "Do Cell Phones Cause Brain Cancer?". Tech Times. Retrieved 3 March 2016.

- ↑ Knibbs, Kate (28 January 2016). "Gwyneth Paltrow's Goop Consults 'Fat Flush' Diet Quack About 'Cell Phone Toxicity'". Gizmodo. Retrieved 4 March 2016.

- ↑ Barrett, Stephen. "Clayton College of Natural Health: Be Wary of the School and Its Graduates". Quackwatch. Retrieved 5 July 2016.

- ↑ "Senate Sub-Committee for Commerce, Science, and Transportation Hearing on Protecting Consumers from False and Deceptive Advertising of Weight-Loss Products". June 17, 2014.

- ↑ "Dr.Oz-endorsed diet pill study was bogus, researchers admit". cbsnews.com. 20 October 2014.

- ↑ "Dr. Oz Green Coffee Bean Study Retracted". The Daily Beast.

- ↑ Leslie Holland, CNN (18 March 2014). "Television pitchman Kevin Trudeau is headed to prison". CNN.

- ↑ Meisner, Jason (2014-03-17). "TV pitchman Kevin Trudeau sentenced to 10 years in prison". chicagotribune.com. Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on 2015-07-01.

- ↑ Choi, Candice (2005-10-04). " 'Natural Cures' book: is it the truth or is it quackery?". quackfiles.blogspot.ca (blog). Associated Press. Archived from the original on 2015-04-05.

- ↑ Godlee F, Smith J, Marcovitch H (2011). "Wakefield's article linking MMR vaccine and autism was fraudulent". BMJ. 342: c7452. PMID 21209060. doi:10.1136/bmj.c7452.

- ↑ Fang, Ferric C.; Steen, R. Grant; Casadevall, Arturo (October 2012). "Misconduct accounts for the majority of retracted scientific publications". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 109 (42): 17028–33. PMC 3479492

. PMID 23027971. doi:10.1073/pnas.1212247109.

. PMID 23027971. doi:10.1073/pnas.1212247109. - ↑ Park, Alice (2012-01-13). "Great science frauds". healthland.time.com. Time. Archived from the original on 2015-04-29.

- ↑ General Medical Council (2010-01-28). "Fitness to Practise Panel hearing 28 January 2010" (PDF). General Medical Council. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2010-02-16. Retrieved 2014-05-31 – via briandeer.com.

Works cited

- Carroll, 2003. "The Skeptics Dictionary". New York: Wiley.

- Della Sala, 1999. Mind Myths: Exploring Popular Assumptions about the Mind and Brain. New York: Wiley.

- Eisner, 2000. The Death of Psychotherapy; From Freud to Alien Abductions. Westport, CT: Praegner.

- Lilienfeld, SO., Lynn, SJ., Lohr, JM. 2003. Science and Pseudoscience in Clinical Psychology. New York: Guildford

- Norcross, JC, Garofalo, A. Koocher, G. 2006. "Discredited Psychological Treatments and Tests; A Delphi Poll". Professional Psychology; Research and Practice. 37(5), 515–22

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Quackery |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Quackery. |

| Look up quackery in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

![]() Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Quack". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Quack". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Quackery at DMOZ

- Medline Plus – entry on Health Fraud

- How to Spot Health Fraud Article from the Food and Drug Administration

- 'Miracle' Health Claims: Add a Dose of Skepticism Article at the Federal Trade Comiision

- Museum of Questionable Medical Devices – Science Museum of Minnesota

- "Quackery." Handbook of Texas.