Haweswater Reservoir

| Haweswater Reservoir | |

|---|---|

Reserview seen from Harter Fell, Mardale | |

| Location | Lake District, Cumbria |

| Coordinates | 54°31′08″N 2°48′17″W / 54.51889°N 2.80472°WCoordinates: 54°31′08″N 2°48′17″W / 54.51889°N 2.80472°W |

| Type | reservoir, natural lake |

| Primary inflows | Mardale Beck, Riggindale Beck |

| Primary outflows | Haweswater Beck |

| Basin countries | England |

| Max. length | 6.7 km (4.2 mi)[1] |

| Max. width | 900 m (3,000 ft)[1] |

| Surface area | 3.9 km2 (1.5 sq mi)[1] |

| Average depth | 23.4 m (77 ft)[1] |

| Max. depth | 57 m (187 ft)[1] |

| Water volume | 76.6×106 m3 (62,100 acre·ft)[1] |

| Residence time | 500 days[1] |

| Surface elevation | 246 m (807 ft) |

| Islands | 1 |

| References | [1] |

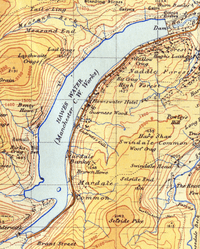

Haweswater is a reservoir in the English Lake District, built in the valley of Mardale in the county of Cumbria. The controversial construction of the Haweswater dam started in 1929, after Parliament passed an Act giving the Manchester Corporation permission to build the reservoir to supply water for Manchester. The decision caused public outcry, since the farming villages of Measand and Mardale Green would be flooded, with their inhabitants needing to be relocated. Also, many desired to maintain the picturesque valley in its existing state.

Creation

Originally, Haweswater was a natural lake about four kilometres long, nearly divided by a tongue of land at Measand; the two reaches of the lake were known as High Water and Low Water. The building of the dam raised the water level by 29 metres (95 feet) and created a reservoir six kilometres (four miles) long and around 600 metres (almost half a mile) wide. The dam wall measures 470 metres long and 27.5 metres high; at the time of construction it was considered to be cutting-edge technology as it was the world's first hollow buttress dam, using 44 separate buttressed units joined by flexible joints. A parapet, 1.4 metres (56 inches) wide, runs the length of the dam and from this, tunnelled supplies can be seen entering the reservoir from the adjoining valleys of Heltondale and Swindale. When the reservoir is full, it holds 84 billion litres (18.6 billion gallons) of water. The reservoir is now owned by United Utilities PLC. It supplies about 25% of the North West's water supply.

Before the valley was flooded in 1935, all the farms and dwellings of the villages of Mardale Green and Measand were demolished, as well as the centuries-old Dun Bull Inn at Mardale Green. The village church was dismantled and the stone used in constructing the dam; all the bodies in the churchyard were exhumed and re-buried at Shap. Today, when the water in the reservoir is low, the remains of the submerged village of Mardale Green can still be seen, including stone walls and the village bridge.

Manchester Corporation built a new road along the eastern side of the lake to replace the flooded highway lower in the valley, and the Haweswater Hotel was constructed midway down the length of the reservoir as a replacement for the Dun Bull. The road continues to the western end of Haweswater, to a car park, a popular starting point for a path to the surrounding fells of Harter Fell, Branstree and High Street.

Lake District writer and fell walker Alfred Wainwright had this to say on the construction of the Haweswater Dam in A Pictorial Guide to the Lakeland Fells:

- "If we can accept as absolutely necessary the conversion of Haweswater [to a reservoir], then it must be conceded that Manchester have done the job as unobtrusively as possible. Mardale is still a noble valley. But man works with such clumsy hands! Gone for ever are the quiet wooded bays and shingly shores that nature had fashioned so sweetly in the Haweswater of old; how aggressively ugly is the tidemark of the new Haweswater!"[2]

Wildlife

Fish

There is a population of schelly fish in the lake, believed to have lived there since the last Ice Age.

RSPB Haweswater

The Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) first became involved in Haweswater because of the presence of golden eagles. The organisation currently manages two farms in the area.

Golden Eagle

Until 2015 Haweswater was the only place in England where a golden eagle was resident. A pair of eagles first nested in the valley of Riggindale in 1969, and the male and female of the pairing changed several times over the years, during which sixteen chicks were produced. The female bird disappeared in April 2004, leaving the male alone.[3] There was an RSPB observation post in the valley for people wishing to see the eagle: the last sighting was in November 2015. It was reported that the 20-year old bird may have died of natural causes.[4]

Farming and conservation

In 2012 the RSPB leased two farms from the landowner United Utilities.[5][6] The aim is to combine the improvement of wildlife habitats and water quality with running a viable sheep farm. Moorland and woodland habitats are being improved for birds as well as the rare small mountain ringlet butterfly. Measures include grip blocking, heather replanting, juniper woodland planting (especially in the ghylls).

Etymology

"Possibly 'Hafr's lake', from a pers.[onal] n.[ame] such as ON [Old Norse] 'Hafr' or a postulated OE [Old English] 'Hæfer', and 'water'... 'wæter OE, water ModE' the dominant term for 'lake'..." [7]

Literary references

Haweswater is a 2002 novel by British writer Sarah Hall, set in Mardale at the time of the building of the dam and flooding of the valley. It won the 2003 Commonwealth Writers' Prize for a First Book. The novel was released in the United States as a paperback original in October 2006, by Harper Perennial.

Hawes Water is described in Anthony Trollope's novel Can You Forgive Her? (1864).

Haweswater is the lake that can be seen from the door of 'Crow Crag' in the film Withnail and I although filming of the cottage itself was done elsewhere.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 McNamara, Jane, Table of lake facts, Environment Agency of England and Wales, archived from the original on 28 June 2009, retrieved 13 November 2007

- ↑ Wainwright, A (2005). A pictorial guide to the Lakeland fells. Book 2: The far Eastern fells (2nd ed. revised by Chris Jesty ed.). London: Frances Lincoln. pp. n.p. "Some personal notes in conclusion". ISBN 9780711224667.

- ↑ "Haweswater". RSPB website. Retrieved 4 March 2007.

- ↑ Aldred, Jessica (2016). "England's last Golden Eagle feared dead". Retrieved 26 May 2016.

- ↑ "RSPB turns to farming". Westmorland Gazette.

- ↑ "New deal for nature and water". 2012.

- ↑ Whaley, Diana (2006). A dictionary of Lake District place-names. Nottingham: English Place-Name Society. pp. lx, 157, 422, 423. ISBN 0904889726.

External links

-

Media related to Haweswater Reservoir at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Haweswater Reservoir at Wikimedia Commons - Lake District Walks - Haweswater

- - Haweswater Estate

- RSPB Haweswater