Hauran

| Auranitis (Hauran) Plateau | |

|---|---|

| سهل حوران | |

The village of Johfiyeh in the Jordanian part of Hauran | |

| Geography | |

|

Satellite view of Syria and surrounding countries with position of Hauran highlighted

| |

| Location | Syria/Jordan |

Auranitis (Hauran) (Arabic: حوران / ALA-LC: Ḥawrān), also spelled Hawran, Houran and Horan,[1] is a volcanic plateau, a geographic area and a people located in southwestern Syria and extending into the northwestern corner of Jordan.

Name

It gets its name from the Aramaic Hawran, meaning "cave land."

Location

In geographic and geomorphic terms, it extends from near Damascus and Mount Hermon in the north to the Ajloun mountains of Jordan in the south. It includes the Golan Heights in the west and is bounded there by the Jordan Rift Valley; it also includes Jabal al-Druze in the east and is bounded there by more arid steppe and desert terrains. The Yarmouk River drains much of the Hauran to the west and is the largest tributary of the Jordan River.

Administrative districts

Today, the Hauran is not a distinct political entity, but encompasses parts of the Syrian governorates of Quneitra, As Suwayda, and Daraa, and parts of the Jordanian governorates of Irbid, Ajloun and Jerash, as well as the western part of Mafraq Governorate. However, the name is used colloquially by both the inhabitants of the region (Hauranis) and outsiders, to refer to the area and its people.

Soil, water, and agriculture

The volcanic soils of Hauran make it one of the most fertile regions in Syria; it produces considerable wheat and is famous for its vineyards. The region receives above-average annual precipitation but has few rivers. Hauran relies mainly on annual snow and rain during winter and spring and many of the ancient sites contain cisterns and water storage facilities to better utilize the seasonal rainfall. The area is unlike other historical fertile areas of Syria (the Orontes and the Euphrates river valleys), which rely on controlled irrigation systems for their farming productivity. Since the mid-1980s, Syria has built a considerable number of seasonal storage dams within the headwaters of the Yarmouk River drainage basin.[2]

History

Prehistory

The plains of Auranitis (Houran) appear to have been initially inhabited by small bands of hunters and gatherers. By circa 12,000 BC, microliths and bone tools were becoming part of daily lifestyle. It is thought that the development of farming around 10,000 BC triggered an agricultural revolution that changed human history and paved the way for the appearance of ancient civilizations after millennia of hunting and gathering in small groups. By this time Natufians settled in Taiyiba in southern Houran, and southwest of Houran in Tabqat Fahl and in the Golan Heights to the west in Nhal ‘En Gev-II as well as all over Canaan.

To their east, circa 8,300 BC wheat was domesticated and their neighbors to the west in Canaan and to the East in Mesopotamia started living in oval houses. Between 8,000 and 7,000 BC, people of Hauran were eating mostly hunted gazelles and foxes. Between 7000 and 6000 BC their daily food was mostly domesticated animals (sheep, goat, pig, and cattle) and domesticated cereals. By the 4th millennium BC (4,000 BC to 3,000 BC) there were many Chalcolithic settlements in the valley of the Yarmouk river.

Hebrew Bible

The Auranitis (Houran) is mentioned in the Hebrew Bible (Ezekiel 47:16-18) including the boundary area of the Israelite northern kingdom at the time. The country's most distinguished citizen is said to have been the prophet Job (Arabic name: Ayyub).[3]

Hellenistic and Roman periods

Centuries later, the Ancient Greeks and Romans referred to the area as Auranitis, and it marked the traditional eastern border of Roman Syria; this is evidenced by the well-preserved Roman ruins in the cities of Bosra and Shahba. At the time, the Hauran also included the northern cities of the Decapolis.

Ottoman period

Atypically, its name is part of that of the Melkite Greek Catholic Archeparchy of Bosra-Haūrān, not just the (historical) main city.

19th-century Swiss traveller Johann Ludwig Burckhardt noted his observation of people from the region:

My companions intending to leave Damascus very early the next morning, I quitted my lodgings in the evening, and went with them to sleep in a small Khan in the suburb of Damascus, at which the Haouaerne, or people of Hauran, generally alight.[4]

Early photographs of Hauran's archaeological sites, taken in the late 19th and early 20th centuries by German explorer and photographer, Hermann Burchardt, are now held at the Ethnological Museum of Berlin.[5]

In the late nineteenth century, the region became an important source of grain and lentil production, and thus attracted the attention of both Ottoman administrators and Damascus merchants alike.[6] The Ottoman state attempted to promote cultivation in the region by settling Circassian refugees there.[6]

Localities

Cities and towns

In alphabetical order, article (Al-, As-, etc.) included.

| | |

|---|---|

| As-Suwayda | Ajloun |

| Busra | Ar Ramtha |

| Daraa | Irbid |

| Qanawat | Jerash |

| Quneitra | |

Villages

In alphabetical order, including article (Al-, Ash-, etc.) and disregarding hyphens.

- Abtaa, Syria

- Aidoon

- Ajami, Syria

- Akaider

- Al-Jiza, Syria

- Al-Mughayyir, Jordan

- Al-Sanamayn, Syria

- Al-Qurayya, Syria

- Al-Yadudah, Syria

- Al-Shaykh Maskin, Syria

- Shajara, Jordan

- Bassir, Syria

- Busra al-Harir, Syria

- Buwaidha

- Da'el, Syria

- Deir al-Bukht, Syria

- Gaittah

- Huwwarah, Jordan

- Izra', Syria

- Jalin (Jileen), Syria

- Jasim, Syria

- Johfiyeh, Jordan

- Khabab, Syria

- Kharab al-Shahem

- Lemtaeyeh

- Lemseifreh

- Lihrak

- Muzayrib, Syria

- Nafia

- Namar, Syria

- Nawa, Syria

- Nuaymah

- Othman, Syria

- Qarfa, Syria

- Saham al-Jawlan, Syria

- Sal, Syria

- Sarih, Syria

- Shajara, Syria

- Tell Shihab, Syria

- Tafas, Syria

- Tubna, Syria

- Umm Walad, Syria

- Zeizun

Archaeological sites

Abandoned ancient towns, forts

- Jawa, Jordan

- Umm el-Jimal, Jordan

- Qasr Burqu' "desert castle"

Roman bridges

Famous local figures

Maps

- Realm of Herod the Great

Geographical regional boundaries, Roman period, map from 1865 atlas

Geographical regional boundaries, Roman period, map from 1865 atlas Golan Heights (1), Trachonitis (2), ...

Golan Heights (1), Trachonitis (2), ...- "Golan, Bashan, Trachonitis, Hauran (?)" on map from Encyclopaedia Biblica (1903)

Claude Reignier Conder, Palestine geological map, showing Hauran (1889)

Claude Reignier Conder, Palestine geological map, showing Hauran (1889) Claude Reignier Conder, Palestine physical map, showing Leja (Trachonitis) and Hauran (1889)

Claude Reignier Conder, Palestine physical map, showing Leja (Trachonitis) and Hauran (1889) Claude Reignier Conder, Palestine in the beginning of the Christian Era, showing Auranitis (1889)

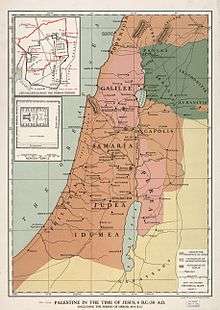

Claude Reignier Conder, Palestine in the beginning of the Christian Era, showing Auranitis (1889) Palestine in the time of Herod and Jesus (40 BCE-30 CE), showing Auranitis (1912)

Palestine in the time of Herod and Jesus (40 BCE-30 CE), showing Auranitis (1912)

Gallery

Dar (House of) Saleem Muhammad -el Hamad- el Gharaibeh in Irbid, Jordan

Dar (House of) Saleem Muhammad -el Hamad- el Gharaibeh in Irbid, Jordan Dar Abu Habis (Dhaifallah el Mahmoud el Gharaibeh) in Irbid, Jordan

Dar Abu Habis (Dhaifallah el Mahmoud el Gharaibeh) in Irbid, Jordan Dar Abu Ghaleb in Irbid, Jordan

Dar Abu Ghaleb in Irbid, Jordan Dar Qasim Tanash Courtesy of Ahmed Abdallah Jameel Gharaibeh in Irbid, Jordan

Dar Qasim Tanash Courtesy of Ahmed Abdallah Jameel Gharaibeh in Irbid, Jordan

References

- ↑ "Cash boost for Syrian rebels to pressure Assad". The National. Abu Dhabi. 5 February 2014. Retrieved 26 July 2015.

- ↑ Jordan River: Johnston negotiations, 1953-55; Yarmuk mediations, 1980s

- ↑ Mukaddasi, Description of Syria, Including Palestine, ed. Guy Le Strange, London 1886, p. 26

- ↑ Travels in Syria and the Holy Land: Journal of an Excursion into the Hauran in the Autumn and Winter of 1810

- ↑ The castle (citadel) of Salkhad, photographed by Hermann Burchardt (click on photo to enlarge it); Melach Es-Sarrar (Malah) in Hauran, in 1895; Dibese, 400 meters west of Suwayda; Qasr (fortress) al-Mushannaf, in Hauran (click to enlarge); The citadel, Khirbat al-Bayda, in Hauran (1895); The ruins of Khirbet al-Bayda.

- 1 2 Gingeras, Ryan (2016). Fall of the Sultanate: The Great War and the End of the Ottoman Empire. Oxford: Oxford. pp. 194–195.