Hartford, Connecticut

| Hartford, Connecticut | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| City | ||||||||

| City of Hartford | ||||||||

From top to bottom, left to right: Downtown Hartford skyline from the Connecticut River, Connecticut State Capitol, Old State House, University of Connecticut School of Law, Hartford Seminary, historic Cheney Building | ||||||||

| ||||||||

|

Nickname(s):

| ||||||||

Location in Hartford County and Connecticut | ||||||||

Hartford  Hartford Location in Connecticut and the United States | ||||||||

| Coordinates: 41°45′45″N 72°40′27″W / 41.76250°N 72.67417°WCoordinates: 41°45′45″N 72°40′27″W / 41.76250°N 72.67417°W | ||||||||

| Country |

| |||||||

| State |

| |||||||

| County | Hartford | |||||||

| NECTA | Hartford | |||||||

| Region | Capitol Region | |||||||

| Settled | 1636 | |||||||

| Named | 1637 | |||||||

| Incorporated (city) | 1784 | |||||||

| Consolidated | 1896 | |||||||

| Government | ||||||||

| • Type | Mayor-council | |||||||

| • Mayor | Luke Bronin (D) | |||||||

| • Council | Hartford City Council | |||||||

| Area | ||||||||

| • City | 18.1 sq mi (46.8 km2) | |||||||

| • Land | 17.4 sq mi (45.0 km2) | |||||||

| • Water | 0.7 sq mi (1.7 km2) | |||||||

| • Urban | 469 sq mi (1,216 km2) | |||||||

| Elevation | 59 ft (18 m) | |||||||

| Population (2010) | 124,775 | |||||||

| • Estimate (2016)[1] | 123,243 | |||||||

| • Density | 7,135/sq mi (2,754.7/km2) | |||||||

| • Urban | 924,859 (US: 47th) | |||||||

| • Metro | 1,214,295 (US: 47th) | |||||||

| • CSA | 1,489,361 (US: 36th) | |||||||

| Time zone | EST (UTC−5) | |||||||

| • Summer (DST) | EDT (UTC−4) | |||||||

| ZIP code | 061xx | |||||||

| Area code(s) | 860 and 959 | |||||||

| FIPS code | 09-37000 | |||||||

| GNIS feature ID | 0213160 | |||||||

| Website |

www | |||||||

Hartford is the capital of the U.S. state of Connecticut. It was the seat of Hartford County until Connecticut disbanded county government in 1960. As of the 2010 Census, Hartford's population was 124,775, making it Connecticut's third-largest city after the coastal cities of Bridgeport and New Haven. Census Bureau estimates since then have indicated Hartford's fall to fourth place statewide, as a result of sustained population growth in the coastal city of Stamford.[2]

Hartford is nicknamed the "Insurance Capital of the World", as it hosts many insurance company headquarters and insurance is the region's major industry. The city was founded in 1635 and is among the oldest cities in the United States. It is home to the nation's oldest public art museum (Wadsworth Atheneum), the oldest publicly funded park (Bushnell Park), the oldest continuously published newspaper (The Hartford Courant), and the second-oldest secondary school (Hartford Public High School). It also is home to Trinity College, a private liberal arts college, and the Mark Twain House where the author wrote his most famous works and raised his family, among other historically significant attractions. Twain wrote in 1868, "Of all the beautiful towns it has been my fortune to see this is the chief."[3]

Following the American Civil War, Hartford was the richest city in the United States for several decades.[4] Today, Hartford is one of the poorest cities in the nation, with 3 out of every 10 families living below the poverty line. In sharp contrast, the Hartford metropolitan area is ranked 32nd of 318 metropolitan areas in total economic production and 7th out of 280 metropolitan statistical areas in per capita income. Highlighting the socio-economic disparity between Hartford and its suburbs, 83% of Hartford's jobs are filled by commuters from neighboring towns who earn over $80,000, while 75% of Hartford residents who commute to work in other towns earn just $40,000.[5]

History

Various tribes lived in or around present-day Hartford, all part of the loose Algonquin confederation. The area was referred to as Suckiaug', meaning "Black Fertile River-Enhanced Earth, good for planting." These included the Podunks, mostly east of the Connecticut River; the Poquonocks north and west of Hartford; the Massacoes in the Simsbury area; the Tunxis tribe in West Hartford and Farmington; the Wangunks to the south; and the Saukiog in Hartford itself.[6]

Colonial Hartford

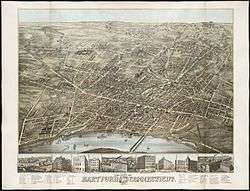

.jpg)

The first Europeans known to have explored the area were the Dutch under Adriaen Block, who sailed up the Connecticut in 1614. Dutch fur traders from New Amsterdam returned in 1623 with a mission to establish a trading post and fortify the area for the Dutch West India Company. The original site was located on the south bank of the Park River in the present-day Sheldon/Charter Oak neighborhood. This fort was called Fort Hoop or the "House of Hope." In 1633, Jacob Van Curler formally bought the land around Fort Hoop from the Pequot chief for a small sum. It was home to perhaps a couple families and a few dozen soldiers. The fort was abandoned by 1654, but the area is known today as Dutch Point; the name of the Dutch fort "House of Hope" is reflected in the name of Huyshope Avenue.[7][8]

The Dutch outpost and the tiny contingent of Dutch soldiers who were stationed there did little to check the English migration, and the Dutch soon realized that they were vastly outnumbered. The House of Hope remained an outpost, but it was steadily swallowed up by waves of English settlers. In 1650, Peter Stuyvesant met with English representatives to negotiate a permanent boundary between the Dutch and English colonies; the line that they agreed on was more than 50 miles (80 km) west of the original settlement.

The English began to arrive 1637, settling upstream from Fort Hoop near the present-day Downtown and Sheldon/Charter Oak neighborhoods.[9] Puritan pastors Thomas Hooker and Samuel Stone, along with Governor John Haynes, led 100 settlers with 130 head of cattle in a trek from Newtown in the Massachusetts Bay Colony (now Cambridge) and started their settlement just north of the Dutch fort.[10] The settlement was originally called Newtown, but it was changed to Hartford in 1637 in honor of Stone's hometown of Hertford, England. (Hooker also created the nearby town of Windsor in 1633.)[11] The etymology of Hartford is the ford where harts cross, or "deer crossing." The Seal of the City of Hartford[12] features a male deer which was referred to by the medieval hunting term hart when in full maturity.

The fledgling colony along the Connecticut River was outside of the jurisdiction of the Massachusetts Bay Colony's charter and had to determine how it was to be governed. Therefore, Hooker delivered a sermon that inspired the writing of the Fundamental Orders of Connecticut, a document ratified January 14, 1639 which invested the people with the authority to govern, rather than ceding such authority to a higher power. Historians suggest that Hooker's conception of self-rule embodied in the Fundamental Orders inspired the Connecticut Constitution, and ultimately the U.S. Constitution. Today, one of Connecticut's nicknames is the "Constitution State."[13]

The original settlement area contained the site of the Charter Oak, an old white oak tree in which colonists hid Connecticut's Royal Charter of 1662 to protect it from confiscation by an English governor-general. The state adopted the oak tree as the emblem on the Connecticut state quarter. The Charter Oak Monument is located at the corner of Charter Oak Place, a historic street, and Charter Oak Avenue.[14]

19th century

Throughout the 19th century, Hartford's residential population, economic productivity, cultural influence, and concentration of political power continued to grow. The advance of the Industrial Revolution in Hartford in the mid-1800s made this city by late century one of the wealthiest per capita in United States.[15]

Political turmoil

On December 15, 1814, delegates from the five New England states (Maine was still part of Massachusetts at that time) gathered at the Hartford Convention to discuss New England's possible secession from the United States.[16] During the early 19th century, the Hartford area was a center of abolitionist activity, and the most famous abolitionist family was the Beechers. The Reverend Lyman Beecher was an important Congregational minister known for his anti-slavery sermons.[17][18] His daughter Harriet Beecher Stowe wrote Uncle Tom's Cabin; her brother Henry Ward Beecher was a noted clergyman who vehemently opposed slavery and supported the temperance movement and women's suffrage.[19][20] Harriet Beecher Stowe's sister Isabella Beecher Hooker was a leading member of the women's rights movement.[21]

In 1860, Hartford was the site of the first "Wide Awakes," abolitionist supporters of Abraham Lincoln. These supporters organized torch-light parades that were both political and social events, often including fireworks and music, in celebration of Lincoln's visit to the city. This type of event caught on and eventually became a staple of mid-to-late-19th century campaigning.[22]

Industrialization and the Colt legacy

Industrialist and inventor Samuel Colt and his wife Elizabeth had a great influence on Hartford's development in the 100 years after independence. Colt is often considered the father of the Connecticut River Valley industrial revolution, although there were a handful of small outfits already in operation by the time that he purchased a large tract of land in the area in the 1840s.

In 1836, Connecticut-born Samuel Colt received a U.S. patent for a revolver mechanism which enabled a gun to be fired multiple times without reloading. Sales were initially slow and his business ventures struggled. Then the U.S. government ordered 1,000 Colt revolvers in 1846, with the Mexican–American War under way. In 1848, Colt was able to start again with a new business of his own, and he converted it into a corporation in 1855 under the name of Colt's Patent Fire Arms Manufacturing Company. The original factory is situated in the Sheldon/Charter Oak neighborhood just south of downtown Hartford.[23]

With business booming by 1855, Colt entered an aggressive expansionary phase and opened the Colt Armory, the world's largest private armament factory. He employed advanced manufacturing techniques such as interchangeable parts and an organized production line. By 1856, the company could produce 150 weapons per day. The Civil War led to a surge in demand, and Colt supplied the Union Army. Colt's Patent Fire-Arms Manufacturing Company operated at full capacity and employed over 1,000 people in its Hartford factory. By that time, Colt had become one of the wealthiest men in America. He was presiding over his enterprise from Armsmear, an ornate Italianate manor built near the armory in 1857. Upon his death in 1862, he was worth over $15 million ($380 million by 2015 standards).[24]

Colt's methods were at the forefront of the Industrial Revolution, and his successes secured Hartford's place as a major 19th century manufacturing center. It is estimated that his company produced over 400,000 revolvers in its first 25 years of manufacturing. His use of interchangeable parts helped him become one of the first to exploit the assembly line.[25] Moreover, his innovative use of art, celebrity endorsements, and corporate gifts to promote his wares made him a pioneer in the fields of advertising, product placement, and mass marketing. His business practices were also innovative, involving a shrewd use of patents to protect his products, as well as new developments in marketing and business organization to create a highly successful business which long outlived him.

Elizabeth Colt inherited a controlling interest in her late husband's manufacturing company following his death in 1862. At the time, Colt firearms were producing an estimated 1/996th of the entire gross national product of the United States. She steered the company until 1901 with her brother Richard Jarvis as president, becoming one of the most prominent female industrialists in America. Together they transitioned the company from the end of the American Civil War into the 20th century, seeing the evolution from percussion revolvers to cartridge revolvers to semiautomatic pistols and machineguns.[26]

In addition, the Colts left an indelible imprint on Hartford's architectural environment. Samuel Colt was inspired by what he had seen during a trip to London in 1851, and he embarked upon one of the boldest real estate development campaigns in Hartford's history. His intention was to build an industrial community to house his workers adjacent to the Colt Armory. By 1856, it was a city within a city, where workers of many nationalities and religions worked and lived alongside one another. Coltsville was among the first of America's 19th century company towns, and it was easily the most advanced of its time—though not the largest, the most prominent, or the most tightly controlled. Colt's complex also included the largest armory in the world, as well as wharf and ferry facilities on the Connecticut River.[27]

A major fire destroyed the original armory in 1864, but Elizabeth Colt had it rebuilt, including its most dramatic feature: the blue onion dome with gold starts, topped by a gold orb and a rampant colt, the original symbol of Colt Manufacturing Company. The Colt Armory is visible to commuters on I-91 and stands as a monument to Hartford's first "celebrity industrialist" and the once mighty empire that he created.[28]

Elizabeth Colt dedicated her final decades to philanthropy and public works. She commissioned the Church of the Good Shepherd in 1896 as a monument to her son following his death. It is built in High Victorian Gothic style, and architectural features include a variety of gun parts, such as bullet molds, gun sights, and cylinders—likely the only church in the world with a gun motif.[29]

With no remaining children, Elizabeth willed her extensive collection of rare art to the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, one of the oldest art galleries in America. The Elizabeth Hart Jarvis Colt Memorial Wing was the first American museum wing to bear the name of a female patron.[30]

When Elizabeth Colt died in 1904, she willed the majority of her estate Armsmear to the City of Hartford for use as a public park. Today the 105 acres (42 ha) Colt Park serves the community with a number of athletic fields, playgrounds, a swimming pool, playground, skating rink, and Dillon Stadium.[31]

Hartford was a major manufacturing city from the 19th century until the mid-20th century. During the Industrial Revolution into the mid-20th century, the Connecticut River Valley cities produced many major precision manufacturing innovations. Among these was Hartford's pioneer bicycle and automobile maker Pope.[32] Many factories have been closed or relocated, or have reduced operations, as in nearly all former Northern manufacturing cities.

Rise of a major manufacturing center

.jpg)

Around 1850, Hartford native Samuel Colt perfected the precision manufacturing process that enabled the mass production of thousands of his revolvers with interchangeable parts. A variety of industries adopted and adapted these techniques over the next several decades, and Hartford became the center of production for a wide array of products, including:

- Colt, Richard Gatling, and John Browning firearms

- Weed sewing machines

- Royal and Underwood typewriters

- Columbia bicycles

- Pope automobiles[33]

The Pratt & Whitney Company was founded in Hartford in 1860 by Francis A. Pratt and Amos Whitney. They built a substantial factory in which the company manufactured a wide range of machine tools, including tools for the makers of sewing machines, and gun-making machinery for use by the Union Army during the American Civil War. Pratt Street (off Main St) continues to reflect this heritage. In 1925, the company expanded into aircraft engine design at its Hartford factory.

Just three years after Colt's first factory opened, the Sharps Rifle Manufacturing Company set up shop in 1852 at a nearby site along the now-buried Park River, located in the present-day neighborhood of Frog Hollow. Their factory heralded the beginning of the area's transformation from marshy farmland into a major industrial zone. The road leading from town to the factory was called Rifle Lane; the name was later changed to College Street and then Capitol Avenue.[34] A century earlier, mills had located along the Park River because of the water power, but by the 1850s water power was approaching obsolescence. Sharps located there specifically to take advantage of the railroad line that had been constructed alongside the river in 1838.

The Sharps Rifle Company failed in 1870, and the Weed Sewing Machine Company took over its factory. The invention of a new type of sewing machine led to a new application of mass production after the principles of interchangeability were applied to clocks and guns. The Weed Company played a major role in making Hartford one of three machine tool centers in New England and even outranked the Colt Armory in nearby Coltsville in size.[34] Weed eventually became the birthplace of both the bicycle and automobile industries in Hartford.

Industrialist Albert Pope was inspired by a British-made, high-wheeled bicycle (called a velocipede) that he saw at the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exposition, and he bought patent rights for bicycle production in the United States. He wanted to contract out his first order, however, so he approached George Fairfield of Weed Sewing Machine Company, who produced Pope's first run of bicycles in 1878.[35] Bicycles proved to be a huge commercial success, and production expanded in the Weed factory, with Weed making every part but the tires. Demand for bicycles overshadowed the failing sewing machine market by 1890, so Pope bought the Weed factory, took over as its president, and renamed it the Pope Manufacturing Company. The bicycle boom was short-lived, peaking near the turn of the century when more and more consumers craved individual automobile travel, and Pope's company suffered financially from over-production amidst falling demand.

In an effort to save his business, Pope opened a motor carriage department and turned out electric carriages, beginning with the "Mark III" in 1897. His venture might have made Hartford the capital of the automobile industry were it not for the ascendancy of Henry Ford and a series of pitfalls and patent struggles that outlived Pope himself.[36]

In 1876, Hartford Machine Screw was granted a charter "for the purpose of manufacturing screws, hardware and machinery of every variety." The basis for its incorporation was the invention of the first single-spindle automatic screw machine. For its next four years, the new firm occupied one of Weed's buildings, milling thousands of screws daily on over 50 machines. Its president was George Fairfield, who ran Weed, and its superintendent was Christopher Spencer, one of Connecticut's most versatile inventors. Soon Hartford Machine Screw outgrew its quarters and built a new factory adjacent to Weed, where it remained until 1948.[37]

20th century

On the week of April 12, 1909, the Connecticut River reached a record flood stage of 24.5 feet (7.47 meters) above the low water mark, flooding the city of Hartford and doing great damage.[38]

On July 6, 1944, Hartford was the scene of one of the worst fire disasters in the history of the United States. It occurred at a performance of the Ringling Brothers and Barnum and Bailey Circus and became known as the Hartford Circus Fire.[39]

After World War II, many residents of Puerto Rico moved to Hartford and Puerto Rican flags can be found on cars and buildings all over the city even today.[40] Former Hartford Mayor Eddie Pérez was born in Puerto Rico and moved to Hartford in 1969 when he was 12 years old.

Starting in the late 1950s, the suburbs ringing Hartford began to grow and flourish and the capital city began a long decline. Insurance giant Connecticut General (now CIGNA) moved to a new, modern campus in the suburb of Bloomfield. Constitution Plaza had been hailed as a model of urban renewal, but it gradually became a concrete office park. Once-flourishing department stores shut down, such as Brown Thomson, Sage-Allen, and G. Fox & Co., as suburban malls grew in popularity, such as Westfarms and Buckland Hills.[41]

In 1997, the city lost its professional hockey franchise, with the Hartford Whalers moving to Raleigh, North Carolina—despite an increase in season ticket sales and an offer from the state for a new arena. In 2005, a developer from Newton, Massachusetts (who was also the city's largest property owner) tried to work with the city to bring an NHL team back to Hartford and house them in a new, publicly funded stadium.[42]

Hartford experienced problems as the population shrank 11 percent during the 1990s. Only Flint, Michigan, Gary, Indiana, Saint Louis, and Baltimore experienced larger population losses during the decade. However, the population has increased since the 2000 Census.[43]

In 1987, Carrie Saxon Perry was elected mayor of Hartford, the first female African-American mayor of a major American city.[44]

21st century

In 2004, Underground Coalition, a Connecticut hip hop promotion company, produced the First Annual Hartford Hip Hop Festival, which also took place at Adriaen's Landing. The event drew over 5,000 fans. A significant number of cultural events and performances take place every year at Mortensen Plaza (Riverfront Recapture Organization) by the banks of the CT River. These events are held outdoors and include live music, festivals, dance, arts and crafts and they are very diverse in ethnicity. Hartford also has a vibrant theater scene with major Broadway productions at the Bushnell Theater as well as performances at the Hartford Stage and Theaterworks (City Arts).[45]

In July 2017, Hartford started considering filing Chapter 9 bankruptcy.[46][47]

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 18.0 square miles (47 km2), of which 17.3 square miles (45 km2) is land and 0.7 square miles (1.8 km2) (3.67%) is water.[48][49]

Hartford is bordered by the towns of West Hartford, Newington, Wethersfield, East Hartford, Bloomfield, South Windsor, and Windsor. The Connecticut River forms the boundary between Hartford and East Hartford, and is located on the east side of the city.[50]

The Park River originally divided Hartford into northern and southern sections and was a major part of Bushnell Park, but the river was nearly completely enclosed and buried by flood control projects in the 1940s.[51] The former course of the river can still be seen in some of the roadways that were built in the river's place, such as Jewell Street and the Conlin-Whitehead Highway.[52]

Climate

Hartford lies in the humid continental climate zone (Köppen Dfa), and is part of USDA Hardiness zone 6b, degrading to 6a in the northern, western, and eastern suburbs away from the Connecticut River valley.[53]

Seasonally, the period from May through October is warm to hot in Hartford, with the hottest months being June, July, and August. In the summer months there is often high humidity and occasional (but brief) thundershowers. The cool to cold months are from November through April, with the coldest months in December, January, and February having average highs in the lower 30's F and overnight lows near 20 F.[54]

The average annual precipitation is approximately 45.9 inches (1,170 mm),[55] which is distributed fairly evenly throughout the year. Hartford typically receives about 44.5 inches (113 cm) of snow in an average winter – about 40% more than coastal Connecticut cities like New Haven, Stamford, and New London.[55] seasonal snowfall has ranged from 115.2 inches (293 cm) during the winter of 1995–96 to 13.5 inches (34 cm) in 1999–2000.[56] During the summer, temperatures reach or exceed 90 °F (32 °C) on an average of 17 days per year,[55] though the record number of occurrences was 38 in 1983 and 1920 saw none. Conversely, on average, temperatures do not rise above freezing on 30 days and dip to 0 °F (−18 °C) or below on 4.0 nights per year.[55] Tropical storms and hurricanes have also struck Hartford, although the occurrence of such systems is rare and is usually confined to the remnants of such storms. Hartford saw extensive damage from the 1938 New England Hurricane, as well as with Hurricane Irene in 2011. The highest officially recorded temperature is 103 °F (39 °C) on July 22, 2011 and the lowest is −26 °F (−32 °C) on January 22, 1961; the record cold daily maximum is −1 °F (−18 °C) on December 2, 1917, while, conversely, the record warm daily minimum is 80 °F (27 °C) on July 31, 1917.[55]

| Climate data for Bradley International Airport, Connecticut (1981–2010 normals,[lower-alpha 1] extremes 1905–present)[lower-alpha 2] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 72 (22) |

73 (23) |

89 (32) |

96 (36) |

99 (37) |

100 (38) |

103 (39) |

102 (39) |

101 (38) |

91 (33) |

83 (28) |

76 (24) |

103 (39) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 55.6 (13.1) |

57.4 (14.1) |

70.1 (21.2) |

82.9 (28.3) |

89.0 (31.7) |

92.8 (33.8) |

95.1 (35.1) |

94.1 (34.5) |

88.7 (31.5) |

79.4 (26.3) |

70.8 (21.6) |

59.0 (15) |

97.2 (36.2) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 34.5 (1.4) |

38.5 (3.6) |

47.7 (8.7) |

60.5 (15.8) |

71.2 (21.8) |

79.6 (26.4) |

84.5 (29.2) |

82.7 (28.2) |

74.9 (23.8) |

63.1 (17.3) |

51.6 (10.9) |

39.7 (4.3) |

60.7 (15.9) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 17.7 (−7.9) |

20.9 (−6.2) |

27.9 (−2.3) |

38.4 (3.6) |

47.7 (8.7) |

57.3 (14.1) |

62.7 (17.1) |

61.1 (16.2) |

52.7 (11.5) |

41.1 (5.1) |

33.2 (0.7) |

23.4 (−4.8) |

40.3 (4.6) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | −2 (−19) |

1.9 (−16.7) |

10.7 (−11.8) |

26.2 (−3.2) |

33.5 (0.8) |

44.2 (6.8) |

51.5 (10.8) |

48.4 (9.1) |

37.8 (3.2) |

26.9 (−2.8) |

17.5 (−8.1) |

6.0 (−14.4) |

−4.5 (−20.3) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −26 (−32) |

−24 (−31) |

−6 (−21) |

9 (−13) |

28 (−2) |

37 (3) |

44 (7) |

36 (2) |

30 (−1) |

17 (−8) |

1 (−17) |

−18 (−28) |

−26 (−32) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.23 (82) |

2.89 (73.4) |

3.62 (91.9) |

3.72 (94.5) |

4.35 (110.5) |

4.35 (110.5) |

4.18 (106.2) |

3.93 (99.8) |

3.88 (98.6) |

4.37 (111) |

3.89 (98.8) |

3.44 (87.4) |

45.85 (1,164.6) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 12.3 (31.2) |

11.0 (27.9) |

6.4 (16.3) |

1.4 (3.6) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

2.0 (5.1) |

7.4 (18.8) |

40.5 (102.9) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 inch) | 10.8 | 9.7 | 11.5 | 11.2 | 12.8 | 12.2 | 10.4 | 10.0 | 9.8 | 10.2 | 10.7 | 10.7 | 130.0 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 inch) | 5.8 | 4.7 | 3.5 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.9 | 4.7 | 20.1 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 63.9 | 63.0 | 60.4 | 58.0 | 63.0 | 67.3 | 68.0 | 70.6 | 72.9 | 69.2 | 68.3 | 68.0 | 66.0 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 169.8 | 176.1 | 213.9 | 228.2 | 258.6 | 273.4 | 293.1 | 269.6 | 223.6 | 199.4 | 139.4 | 139.5 | 2,584.6 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 58 | 59 | 58 | 57 | 57 | 60 | 64 | 63 | 60 | 58 | 47 | 49 | 58 |

| Source: NOAA (relative humidity and sun 1961–1990)[55][58][59] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1790 | 2,683 | — | |

| 1800 | 3,523 | 31.3% | |

| 1810 | 3,955 | 12.3% | |

| 1820 | 4,726 | 19.5% | |

| 1830 | 7,074 | 49.7% | |

| 1840 | 9,468 | 33.8% | |

| 1850 | 17,966 | 89.8% | |

| 1860 | 29,152 | 62.3% | |

| 1870 | 37,180 | 27.5% | |

| 1880 | 42,015 | 13.0% | |

| 1890 | 53,230 | 26.7% | |

| 1900 | 79,850 | 50.0% | |

| 1910 | 98,915 | 23.9% | |

| 1920 | 138,036 | 39.6% | |

| 1930 | 164,072 | 18.9% | |

| 1940 | 166,267 | 1.3% | |

| 1950 | 177,397 | 6.7% | |

| 1960 | 162,178 | −8.6% | |

| 1970 | 158,017 | −2.6% | |

| 1980 | 136,392 | −13.7% | |

| 1990 | 139,739 | 2.5% | |

| 2000 | 121,578 | −13.0% | |

| 2010 | 124,775 | 2.6% | |

| Est. 2016 | 123,243 | [1] | −1.2% |

| Population 1800–1990[60] | |||

.png)

As of the census[61] of 2010, there were 124,775 people, 44,986 households, and 27,171 families residing in the city. The population density was 7,025.5 people per square mile (2,711.8/km²). There were 50,644 housing units at an average density of 2,926.5 per square mile (1,129.6/km²). The racial makeup of the city was 29.8% white, 38.7% African American or black, 0.6% Native American, 2.8% Asian, 0% Pacific Islander, 23.9% from other races, and 4.2% from two or more races. 43.4% of the population were Hispanic or Latino, chiefly of Puerto Rican origin.[62] Whites not of Latino background were 15.8% of the population in 2010,[63] down from 63.9% in 1970.[64]

There were 44,986 households, out of which 34.4% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 25.2% were married couples living together, 29.6% had a female householder with no husband present, and 39.6% were non-families. 33.2% of all households were made up of individuals and 9.6% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.58 and the average family size was 3.33.[63]

In the city, the population distribution skews young: 30.1% under the age of 18, 12.6% from 18 to 24, 29.8% from 25 to 44, 18.0% from 45 to 64, and 9.5% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 30 years. For every 100 females, there were 91.4 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 86.0 males.[63]

The median income for a household in the city was $20,820, and the median income for a family was $22,051. Males had a median income of $28,444 versus $26,131 for females. The per capita income for the city was $13,428.[63]

As of 2010, 33.7% of Hartford residents claimed Puerto Rican heritage.[63] This was the second-largest concentration of Puerto Ricans in the Northeast, behind only Holyoke, Massachusetts, approximately 30 miles (48 km) to the north along the Connecticut River.[65][66]

Government

Hartford is governed via the strong-mayor form of the mayor-council system. The current mayor is Luke Bronin. In 2015, Bronin succeeded former mayor Pedro Segarra, who was sworn in as mayor on June 25, 2010, was Hartford's second mayor of Puerto Rican ancestry, and the first openly gay mayor of the city.[67][68]

More than fifty years after establishing the council-manager form, Hartford voted in favor of restoring a mayor-council system in 2003, restoring municipal authority in an elected mayor in 2003. Mayor Eddie Perez, first elected in 2001, was re-elected with 76% of the vote in 2003. As the first strong mayor elected under the revised charter, he is widely credited with reducing crime, reforming the school system and sparking economic revitalization in the city. However, his reputation was hurt by accusations of corruption.[69]

In Connecticut there is no county-level executive or legislative government; the counties determine probate, civil and criminal court boundaries, but little else. Connecticut municipalities (like those of neighboring states Massachusetts and Rhode Island) provide nearly all local services (such as fire and rescue, education, snow removal, etc.), as county government has been abolished since 1960.[70]

| Voter registration and party enrollment as of October 27, 2015[71] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Active voters | Inactive voters | Total voters | Percentage | |

| Democratic | 36,034 | 5,226 | 41,260 | 71.53% | |

| Republican | 1,723 | 321 | 2,044 | 3.54% | |

| Unaffiliated | 11,771 | 2,241 | 14,012 | 24.29% | |

| Minor Parties | 336 | 31 | 367 | 0.64% | |

| Total | 49,864 | 7,819 | 57,683 | 100% | |

City council

| Name | Position | Political affiliation |

|---|---|---|

| Thomas J. Clarke II | President | Democrat |

| Julio A. Concepción | Majority leader | Democrat |

| John Q. Gale | Councilman | Democrat |

| Glendowlyn H. Thames | Councilwoman | Democrat |

| James B. Sanchez | Councilman | Democrat |

| Jo Winch | Councilwoman | Democrat |

| Wildaliz Bermudez | Minority leader | Working Families |

| Larry Deutsch | Councilman | Working Families |

| Cynthia Renee Jennings | Councilwoman | Working Families |

Fire

The Hartford Fire Department provides fire protection and first responder emergency medical services to the city of Hartford. Operating out of 12 fire stations located throughout the city, the HFD is the fifth-largest fire department in Connecticut. Under the command of two Deputy Chiefs in two Districts, the HFD maintains a fire apparatus fleet of eleven engines, five ladders, one tac unit (rescue), one fireboat, one rehab unit, one decon Unit, one foam unit, one fire investigation unit, three Maintenance Units, and numerous other spare apparatus. The spare apparatus fleet comprises six spare engines, three spare ladders, one spare tac, and three spare district chief's units.[74][75]

Police

The Hartford Police Department (HPD) was founded in 1860, though the history of law enforcement in Hartford begins in 1636.[76] The current Hartford Police Chief is James C. Rovella.[77] The department is located at 253 High Street and includes divisions such as Animal Control, Bomb Squad, Detective Bureau, K-9 Unit, Marine Division, Records, E.R.T., and Vice & Narcotics. To date seven officers have died in the line of duty.[78] The proposed 2010–2011 budget for the police department was $76,110,089, which included 424 sworn officers.[79]

Ambulance

Hartford outsources ambulance services to private companies, including Aetna Ambulance in the South End and American Medical Response in the North End.[80]

Neighborhoods

The central business district, as well as the State Capitol, Old State House and a number of museums and shops are located Downtown.[81] Parkville, home to Real Art Ways, is named for the confluence of the north and the south branches of the Park River.[82] Frog Hollow, in close proximity to Downtown, is home to Pope Park and Trinity College, which is one of the nation's oldest institutions of higher learning.[83] Asylum Hill, a mixed residential and commercial area, houses the headquarters of several insurance companies as well as the historic homes of Mark Twain and Harriet Beecher Stowe.[84] The West End, home to the Governor's residence, Elizabeth Park, and the University of Connecticut School of Law, abuts the Hartford Golf Club.[85] Sheldon Charter Oak is renowned as the location of the Charter Oak and its successor monument as well as the former Colt headquarters including Samuel Colt's family estate – Armsmear.[86] The North East neighborhood is home to Keney Park and a number of the city's oldest and ornate homes.[87] The South End features "Little Italy" and was the home of Hartford's sizeable Italian community.[88] South Green hosts Hartford Hospital.[89] The South Meadows is the site of Hartford–Brainard Airport and Hartford's industrial community.[90] The North Meadows has retail strips, car dealerships, and Comcast Theatre.[91] Blue Hills is home of the University of Hartford and also houses the largest per capita of residents claiming Jamaican-American heritage in the United States.[92] Other neighborhoods in Hartford include Barry Square, Behind the Rocks, Clay Arsenal, South West, and Upper Albany- which is dotted by many Caribbean restaurants and specialty stores.[93]

In 2010, Hartford ranked 19th in the United States' annual national crime rankings (below the 200.00 rating).[94] It had the second highest crime rate in Connecticut, behind New Haven. Statistically Hartford's Northern districts (North East, Asylum Hill, Upper Albany) had the highest murder rate, while the South districts (Downtown, Sheldon, South Green) had a slightly lower murder rate, but had the most crime overall. Overall, the South Meadows neighborhood had the lowest crime rate, respectively.[95]

Economy

Hartford is the historic international center of the insurance industry, with companies such as Aetna, Conning & Company, The Hartford, The Phoenix Companies, and Hartford Steam Boiler based in the city, and companies such as Travelers and Lincoln National Corporation having major operations in the city. The city is also home to the corporate headquarters of U.S. Fire Arms and United Technologies.[96]

Aetna and the Hartford Financial Services Group, both Fortune 100 companies, are headquartered in Hartford. Travelers Insurance has its largest national employment center and historical headquarters in the city. CIGNA insurance is headquartered in the region with a presence in Hartford and its suburb Bloomfield. United Health Insurance has a significant presence in the city.[97]

At the same time, many companies have moved to or expanded in the central business district and surrounding neighborhoods. Aetna announced mid-decade that by 2010 it would move nearly 3,500 employees from its Middletown, Connecticut offices to its corporate headquarters in the Asylum Hill section of the city.[98] Travelers recently expanded its operations at several downtown locations.[99] In 2008, Sovereign Bank consolidated two bank branches as well as its regional headquarters in a nineteenth-century palazzo on Asylum Street.[100] In 2009, Northeast Utilities, a Fortune 500 company and New England's largest energy utility, announced it would establish its corporate headquarters downtown.[101] Other recent entrants into the downtown market include GlobeOp Financial Services and specialty insurance broker S.H. Smith. CareCentrix, a patient home healthcare management company, is moving into downtown from East Hartford, where it will add over 200 jobs within the next few years.

Hartford is a center for medical care, research, and education. Within Hartford itself the city includes Hartford Hospital, The Institute of Living, Connecticut Children's Medical Center, and Saint Francis Hospital & Medical Center (which merged in 1990 with Mount Sinai Hospital).[102]

After rising during the Great Recession to over 9% during 2010, unemployment in Connecticut had fallen by December 2014 to 6.4%, .6 above the national average of 5.8%.[103]

Media

The daily Hartford Courant newspaper is the country's oldest continuously published newspaper, founded in 1764. A weekly newspaper, owned by the same company that owns the Courant, the Hartford Advocate, also serves Hartford and the surrounding area, as does the Hartford Business Journal ("Greater Hartford's Business Weekly") and the weekly Hartford News.[104]

The Hartford region is also served by several magazines. Among the local publications are: Hartford Magazine,[105] a monthly lifestyle magazine serving Greater Hartford; CT Cottages & Gardens,[106] Connecticut Business,[107] a glossy monthly serving all of Connecticut; and Home Living CT,[108] a home and garden magazine published five times a year and distributed statewide.

Several television and radio stations are based in Hartford, including Connecticut Public Television, which is headquartered in Hartford. In addition to Connecticut Public Television, Hartford's major television stations include WFSB 3 (CBS), WTNH 8 (ABC), WVIT 30 (NBC O&O), WTIC-TV 61 (Fox), WCCT-TV 20 (The CW), and WCTX 59 (MyNetworkTV). These stations serve the Hartford/New Haven market, which is the 29th largest media market in the U.S.[109]

Education

Colleges and universities

Hartford houses several world-class institutions such as Trinity College.[110] Other notable institutions include Capital Community College (located Downtown in the old G. Fox Department Store building on Main Street), the University of Connecticut School of Business (also Downtown), the Hartford Seminary (in the West End), the University of Connecticut School of Law (also in the West End) and Rensselaer at Hartford (a Downtown branch campus of Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute). University of Saint Joseph opened its school of pharmacy in the downtown area in 2011.[111] The University of Hartford features several cultural institutions: the Joseloff Gallery, the Renee Samuels Center, and the Mort and Irma Handel Performing Arts center. The "U of H" campus is co-located in the city's Blue Hills neighborhood and in neighboring towns West Hartford and Bloomfield.[112]

Primary and secondary education

Hartford is served by the Hartford Public Schools.[113] Hartford Public High School, the nation's second-oldest high school, is located in the Asylum Hill neighborhood of Hartford.[114] The city is also home to Bulkeley High School on Wethersfield Avenue, Global Communications Academy on Greenfield Avenue, Weaver High School on Granby Street, and Sport Medical and Sciences Academy on Huyshope Avenue. In addition, Hartford contains The Learning Corridor, which is home to the Montessori Magnet School, Hartford Magnet Middle School, Greater Harford Academy of Math and Science, and the Greater Hartford Academy of the Arts. One of the technical high schools in the Connecticut Technical High School System, A.I. Prince Technical High School, also calls the city home. The Classical Magnet School is one of the many Hartford Magnet Schools. The city's high school graduation rate reached 71 percent in 2013, according to the state Department of Education.[115] Hartford is also home to Watkinson School, a private coeducational day school, and Grace S. Webb School, a special education school. Catholic schools are administered by the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Hartford.

Transportation

Highways

I-84 which runs from Scranton, to its intersection with I-90 in Sturbridge, just over the Massachusetts border, and I-91, which runs from New Haven along the Connecticut River ultimately to Canada, intersect in downtown Hartford.[116] In addition to I-84 and I-91, two other highways service the city: Route 2, an expressway that runs from downtown Hartford to Westerly, passing through Norwich and past Foxwoods Resort Casino.[117] The Wilbur Cross Highway portion of Route 15 that skirts the southeastern part of the city near Brainard Airport.[118] A short connector known as the Conlin–Whitehead Highway also provides direct access from I-91 to the Capitol Area of downtown Hartford.[119] The Main St. Bridge is a historic bridge on the highway.[120]

Hartford experiences heavy traffic as a result of its substantial suburban population (nearly 10 times that of the actual city). As a result, thousands of people travel on area highways at the start and end of each workday. I-84 experiences traffic from Farmington through Hartford and into East Hartford and Manchester during the rush hour.[121][122]

Several major surface arteries also run through the city. Albany Avenue (Route 44) runs westward through the northern part of West Hartford to the Farmington Valley and the hills of northern Litchfield County and into New York, and eastward towards Putnam and into Rhode Island.[123] Blue Hills Avenue (Route 187) runs north from Albany Avenue toward Bloomfield and East Granby.[124] Main Street (Route 159) heads north through Windsor towards the western suburbs of Springfield, Massachusetts.[125] Wethersfield Avenue (Route 99) heads south through Wethersfield towards Middletown.[126] Maple Avenue heads south-southwest, becoming the Berlin Turnpike in Wethersfield and Newington. Farmington Avenue heads west through West Hartford Center and Farmington towards Torrington.[127]

A large-scale project is being built, rebuilding I-84.[128]

Rail

Amtrak provides service from Hartford to Vermont, via Springfield (and from there to points west, e.g. to Chicago, or east through the western suburbs of Boston), and southward to New Haven, with connections to New York, Boston, Providence, and Washington DC. The station also serves numerous bus companies because of Hartford's mid-way location on the New York to Boston route.[129]

As of late 2016, there are plans to create a commuter rail service connecting New Haven to Springfield via Hartford. Called the Hartford Line, it will stop at stations in communities along I-91. It will use the rail line currently used by Amtrak, which was formerly part of the New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad system. The commuter rail line is anticipated to open in January 2018, and is currently under construction.[130]

Airports

Bradley International Airport (BDL), in Windsor Locks, Connecticut, is about halfway between Hartford and Springfield, Massachusetts. It features over 150 daily departures to over 30 destinations on nine airlines. Connecticut Transit's 30-Bradley Flyer route provides semi-express bus service between Bradley International Airport and downtown Hartford for a low local bus fare (the one-way fare is $1.50). The Bradley Flyer provides direct service to the Connecticut Convention Center, Union Station, and other downtown Hartford points of interest. Other airports serving the Hartford area include:[131]

- Hartford-Brainard Airport (HFD), located in Hartford off I-91 and close to Wethersfield, serves charter flights and local flights.[132]

- Westover Metropolitan Airport (CEF), located in Chicopee, Massachusetts, 27 miles (43 km) north of Hartford, serves commercial, local, charter, and military flights.[133]

- Tweed New Haven Regional Airport (HVN), located in New Haven, Connecticut, is served by American Eagle.[134]

Bus

Connecticut Transit (CTtransit) is owned by the Connecticut Department of Transportation. The Hartford Division of CTtransit operates local and commuter bus service within the city and the surrounding area. Hartford's Downtown Area Shuttle (DASH) bus route is a free downtown circulator. Additionally, all city buses are equipped with bike racks.[135]

In March 2015, CTfastrak, Connecticut's first bus rapid transit system, opened, providing a separated right-of-way between Hartford and New Britain. In addition, express bus services travel from downtown Hartford and Waterbury, servicing intermediate suburban communities like Southington and Cheshire, providing reliable public transportation between these communities for the first time. CTfastrak consists of 10 stations along the dedicated New Britain to Hartford busway, as well as a downtown loop serving Union Station and other downtown landmarks. Amenities include high-level station platforms, on-board wi-fi, ticket machines for pre-boarding fare collection, and real-time arrival information at stations.[136][137]

Interstate bus service is provided by Peter Pan Bus, Greyhound Bus and Megabus. Chinatown bus lines provide low-cost bus service between Hartford and their New York and Boston hubs. In addition, there are buses for connections to smaller cities in the state. The main bus station is located on the ground floor of the transport center at Hartford Union Station at One Union Place, serving Peter Pan Bus and Greyhound Bus customers. All Megabus arrivals and departures are at the corner of Columbus Boulevard and Talcott Street on the opposite side of downtown.[138][139]

Bicycle

A bicycle route runs through the center of Hartford. This route is a small piece of the large eastern bicycle route – the East Coast Greenway (ECG). The 3,000-mile (4,800 km) ECG runs from Calais, Maine to the Florida Keys. The route is intended to be off-road, but some sections are currently on-road. The section through Hartford is right through the middle of Bushnell Park.[140][141][142]

There are designated bicycle lanes on several roads including Capitol Avenue, Zion Street, Scarborough Lane, Whitney, and South Whitney.[143]

Culture

Points of interest

- Aetna Headquarters – The world's largest colonial revival building, the Aetna headquarters on Farmington Avenue is crowned by a tall Georgian tower inspired by the Old State House downtown.[144]

- Ancient Burying Ground – The oldest historic site in Hartford. It was Hartford's first graveyard. Many of Hartford's first renowned residents and founders are buried there.[145]

- Armsmear – The Colt family estate.[146]

- Bulkeley Bridge – Spanning the Connecticut River and connecting the city of Hartford with East Hartford, the nine-span structure is a stone-arch bridge.[147]

- Bushnell Center for the Performing Arts – Constructed in the 1930s by the same architects who designed New York City's Radio City Music Hall, the theater features a Georgian Revival exterior and an exquisite Art Deco interior, with a large hand-painted mural suspended from the ceiling that is the largest of its kind in the United States.[148]

- Bushnell Park – Located below the State Capitol and legislative office complex, this park consists of rolling lawn, sculpture, fountains, and a historic carousel. It is the first park in the country purchased by a municipality for public use, and it was designed by Jacob Weidenmann. The Soldiers & Sailors Memorial Arch, a Civil War Memorial, which frames the northern entrance to the park, is the first triumphal arch in the United States.[149]

- Cathedral of St. Joseph – Located west of downtown along Farmington Avenue in the Asylum Hill neighborhood, this 281-foot (86 m) limestone Roman Catholic cathedral (built in 1961 to replace its predecessor lost to fire) has large Parisian stained glass windows, an 8,000 pipe organ, and the largest ceramic tile mural of Christ in Glory in the world.[150]

- Center Church – The First Church of Christ in Hartford, located at 60 Gold Street and also known as Center Church, has stood at the corner of Main and Gold Streets in downtown Hartford for more than two centuries and was founded by Thomas Hooker.[145]

- Cheney Building – Constructed in the late 19th-century, this notable building by famed architect H. H. Richardson is located Downtown on Main Street. It housed the Brown, Thomson & Co. department store.[151]

- City Place I- The tallest building in Hartford at 38 stories and the tallest building in Connecticut. It is located at 185 Asylum Street.[152]

- Colt Armory – Topped with a blue and gold dome, the complex was once the main factory building of Colt's Manufacturing Company. It is currently being redeveloped and renovated and will feature apartments, retail and office space.[153]

- Xfinity Theater (formerly the Meadows Music Theater) – Located in the North Meadows, it is an indoor/outdoor amphitheater-style performance venue.[154]

- Connecticut Science Center – 154,000 square foot (14,000 m²), nine-story, $165 million museum. Designed by César Pelli, it opened on June 12, 2009.[155]

- Connecticut State Library & Supreme Court – Located in the hill district near the State Capitol atop Bushnell Park, the building also contains the Museum of Connecticut History and a number of galleries devoted to Samuel Colt memorabilia.[156]

- Connecticut Convention Center – The 540,000 square foot (42,000 m²) convention center is now open, and overlooks the Connecticut River and the central business district. Attached to the center is a new 409 room, 22-story Marriott Hotel (opened late August 2005).[157]

- Connecticut Governor's Mansion – An imposing Georgian revival mansion situated near the highest point in the City of Hartford on upper Prospect Avenue. Four landscaped acres surround the residence continuing the garden setting of Elizabeth Park, just opposite Asylum Avenue.[158]

- Connecticut Opera – Founded in 1942, is the six-oldest opera company in the United States, performing three fully staged operas per season, primarily at The Bushnell Center for the Performing Arts in Hartford.[159]

- Connecticut State Capitol – Located atop Bushnell Park, this large Gothic-inspired building features many statues and engravings on its exterior. It is topped with a gold leafed dome.[160]

- Constitution Plaza – Built in the early 1960s, Constitution Plaza is a renowned, and notorious, redevelopment project. To build the plaza, Hartford's historic Front Street neighborhood was razed. The complex is composed of numerous office buildings, underground parking, a restaurant, broadcasting studio, and outdoor courtyards and fountains. During the holiday season the area is filled with Christmas lights for the Festival of Light. The Plaza passes over I-91 and connects the city to the Connecticut River by way of Riverfront Plaza.[161]

- Elizabeth Park & Rose Garden – Straddling the Hartford/West Hartford border, both sections of the park administered by the City of Hartford.[162]

- Harriet Beecher Stowe House & Research Center – The former home of Harriet Beecher Stowe, located in Nook Farm, the Asylum Hill neighborhood on Farmington Avenue, has become a museum, along with its neighbor – the home of Mark Twain.[163]

- The Hartford Financial Services Group headquarters campus on Asylum Hill occupies the former site of the American School for the Deaf, which has moved to a campus in West Hartford.[164]

- Hartford Public Library – The Library was founded in 1774 and has over 500,000 holdings, an extensive calendar of programs and free public access computers and Wifi.[165]

- Hartford Symphony Orchestra – Connecticut's regional orchestra.[166]

- The Hartt School at the University of Hartford is recognized as one of the premiere performing arts conservatories in the United States.[167]

- The Mark Twain House and Museum – The home was built by Samuel Clemens and his wife in 1874. They lived here 17 years, raising three daughters. This is where Mark Twain wrote many of his most popular books. The house is open year-round for tours, events, and author programs. It is located in Nook Farm,[163] part of the Asylum Hill neighborhood, on Farmington Avenue. National Geographic named it one of the ten best historic homes in the world.[168]

- Old State House – The Old State House, dating back to 1796, makes it one of the nation's oldest. It was designed by Charles Bulfinch, who later went on to design the Massachusetts State House in Boston. Recently restored with a gold-leafed dome rising from its top, the Old State House sits facing the Connecticut River in Downtown. The Old State House was the site of the Amistad trial.[169]

- Phoenix Life Insurance Company Building – The first two-sided building in the world, it is located on Constitution Plaza and listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[170]

- Pope Park – Public park originally landscaped by the Olmsted brothers.[171]

- Real Art Ways – An alternative art gallery and hosts contemporary art, music, and film productions.[172]

- Soldiers and Sailors Memorial Arch – Located in Bushnell Park, the now buried Park River once flowed beneath it. Honoring the 4,000 Hartford citizens who served in the American Civil War, and the 400 who perished, the brownstone memorial is the first triumphal arch in the United States.[173]

- Trinity College – The liberal arts college was founded in 1823 and has more than 2,100 students. It is the second-oldest in Connecticut after Yale University in New Haven.[110]

- University of Connecticut School of Business – A branch of the University of Connecticut Business school operates in downtown Hartford. The building is located on Market Street, north of Constitution Plaza.[174]

- University of Connecticut School of Law – located off Farmington Avenue, the campus features an extensive Gothic-inspired library.[175]

- University of Hartford – The university, which was founded in 1877, sits on 340 acres (140 ha) with a 13-acre (5.3 ha) campus on Bloomfield Avenue situated on land divided between Hartford, West Hartford and Bloomfield. Located in the Blue Hills neighborhood, the campus is minutes from Downtown. There are more than 7,200 students and 86 undergraduate majors.[112]

- Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art – The oldest art museum in the U.S. is located on Main Street in downtown Hartford opposite the Travelers Tower. The museum features a significant collection of Italian Baroque old masters and post-impressionist modern art. In the plaza located between it and Hartford Municipal Building, Alexander Calder's 'Stegosaurus' sculpture sits in an open-air plaza.[176]

- XL Center – Built in 1975, the center hosts concerts and shows. Formerly home to the NHL Hartford Whalers, it is currently the home to the Hartford Wolf Pack AHL hockey team and, part-time, to the UConn Huskies basketball team.[177]

- Dunkin' Donuts Park – A baseball field that opened up on April 13, 2017 that currently hosts the Hartford Yard Goats.[178]

Parades

- Greater Hartford St. Patrick's Day Parade – Downtown – March – Run by The Central Connecticut Celtic Cultural Committee.[179]

- Greater Hartford Puerto Rican Day Parade – Downtown, South Green, and Frog Hollow – June – Run by The Connecticut Institute for Community Development.[180]

- Greater Hartford West Indian Parade – Northeast – August – Run by The West Indian Independence Celebrations since 1962.[181]

- Hooker Day Parade – Downtown – May – Run by Hartford Business Improvement District.[182]

- Connecticut Veterans Parade – Downtown – November – Run by The Ferris Group, LLC.[183]

Sports

| Club | League | Venue | Founded | Titles |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hartford Yard Goats | EL, Baseball | Dunkin' Donuts Park | 1983 | 2 |

| Hartford Wolf Pack | AHL, Ice hockey | XL Center | 1926 | 1 |

The Hartford Wolf Pack of the American Hockey League plays ice hockey at the XL Center in downtown Hartford.[184] The XL Center also hosts larger-profile games for both the men's and women's basketball teams of the UConn Huskies. Other UConn home games are played at Gampel Pavilion located on the university's campus in Storrs.

The Hartford Yard Goats, the Double-A affiliate of the Colorado Rockies, moved to Hartford in 2017, moving from New Britain. The team currently play at Dunkin' Donuts Park. The move was made in an effort to keep the team from leaving the state for nearby Springfield, Massachusetts.[185]

Former teams

Hartford became the home of the WHA's New England Whalers in 1975 after the club moved from Boston, one of four WHA teams that joined the NHL in 1979. The city was home to the NHL's Hartford Whalers from 1979 to 1997, before the team relocated to Raleigh, North Carolina and became the Carolina Hurricanes.[186]

The Boston Celtics played various home games per year in Hartford from 1975 until 1995, when they opened the new TD Garden.[187]

Hartford was also home to the Hartford Hellions of the Major Indoor Soccer League (MISL).[188]

Hartford also used to have a National League baseball team, the Hartford Dark Blues, back in the 1870s, and had an NFL team, the Hartford Blues, for three seasons in the 1920s.[189]

Hartford briefly had a team in the UFL called the Hartford Colonials, but games were played in neighboring East Hartford's Rentschler Field.[190]

Recent developments

- Adriaen's Landing – The state and privately funded project is situated on the banks of the Connecticut River along Columbus Boulevard, and connects to Constitution Plaza. Constitution Plaza forced hundreds of households to relocate when it was built a few decades ago. The latest project includes the 540,000-square-foot (50,000 m2) Connecticut Convention Center, which opened in June 2005 and is the largest meeting space between New York City and Boston. Attached to the Convention Center is the 22-story, 409 room Marriott Hartford Hotel-Downtown, which opened in August 2005. Being constructed next to the convention center and hotel is the 140,000-square-foot (13,000 m2) Connecticut Science Center.[191]

- Capital Community College at the 11-story G. Fox Department Store Building – The 913,000-square-foot (84,800 m2) former home of the G. Fox & Company Department Store on Main Street has been renovated and made the new home of Capital Community College as well as offices for the State of Connecticut and ground level retail space. Capital Community College helps train (mostly) adult students in specific career fields. On Thursdays, vendors sell crafts on the Main Street level. Two music clubs, Mezzanine and Room 960, are housed in the building.[192]

- CTfastrak – The recently completed bus rapid transit system connects Hartford's Union Station to downtown New Britain. It was built to ease traffic on I-84.[193]

- Front Street – The final component of Adriaen's Landing, 'Front Street', sits across from the Convention Center and covers the land between Columbus Boulevard and The Hartford Times Building. The Front Street development combines retail, entertainment and residential components. Publicly funded parts of the project will include transportation improvements. There have been significant delays in the Front Street project – the first developer was removed from the project because of lack of progress. The city has chosen a new developer, but work is yet to begin on the retail and residential component of Front Street. The city and state may soon take action to increase the speed with which the project enters implementation phases. There has been talk of bringing an ESPN Zone to the Front Street (ESPN is headquartered in nearby Bristol).[194] On the back side of Front Street, the historic Beaux-Arts Hartford Times Buildinzg is being converted into a downtown campus of the University of Connecticut.[195]

- Hartford Line – According to Connecticut Governor Malloy, the Hartford Line commuter rail service will reach speeds up to 110 mph (177 km/h).[196] The rail line is intended to unite the densely populated, 61 mile (91 km) region between Hartford, Springfield, and New Haven; ease the frequently congested Interstate 91 automobile highway; and increase mobility in a region that is now almost entirely dependent upon automobile ownership. As of May 2011, Connecticut's portion of the commuter line has been 3/4 funded. Currently, the state is seeking the $227 million necessary to complete the northern portion of the line from the $2.4 billion in Federal funds that Florida rejected to fund its own high-speed rail project.[196]

- Knowledge Corridor Partnership – In 2000, at The Big E in West Springfield, Massachusetts, Hartford and Springfield, Massachusetts – the two major New England, Connecticut River Valley cities with centers only 24 miles (37 km) apart – jointly announced the Knowledge Corridor Partnership. The Knowledge Corridor Partnership aims to unite the two metropolitan areas economically, culturally, and geographically. The nickname comes from the metropolitan region's over 32 universities and liberal arts colleges, including several of the United States' most prestigious. As of the 10th anniversary of the Knowledge Corridor, it was announced that the Knowledge Corridor is beginning to receive federal funds, as opposed to either state or city.[197]

- New condos and apartments:

- Spectra Boutique Apartments – The former 300 room Sonesta Hotel at 5 Constitution Plaza was converted into 190 luxury rental apartments in 2015 by New York City Developers Girona Ventures and Wonder Works Construction & Development Corp. The building was awarded the Best of Hartford: 2017 for Best Upscale Apartment Building.[198]

- Hartford 21 – On the site of the former Hartford Civic Center Mall (now known as the XL Center), the project includes a 36 story residential tower—the tallest residential tower between New York City and Boston, and is located at the intersection of Trumbull Street and Asylum Street. Attached to the tower is 90,000 square feet (8,000 m²) of office space and 45,000 square feet (4,200 m²) of retail space, all contained within a connected complex.[199]

- Trumbull on the Park – Recently opened along Bushnell Park, this apartment community is housed in a new 11-story brick building along with a parking garage and ground-level retail space. Additional units are housed in recently renovated historic buildings on nearby Lewis Street.[200]

- Sage Allen Building – On Main Street, the former Sage Allen department store building has been turned into 44 4-bedroom townhouses as well as an upscale apartment building comprising about 70 units that opened in January 2007. The project also includes the renovation of the Richardson Food Court and the reopening of Temple Street, which once again reconnects Main and Market Streets. Many of the townhouses will be occupied by University of Hartford students. It sits directly across Market Street from the University of Connecticut Graduate Business Learning Center.[201]

- American Airlines Building – Located at 915 Main Street across from Capital Community College and the Residence Inn by Marriott, the site was formerly home to an E. J. Korvette department store and later American Airlines. The building has been converted into apartments with renovated ground-level retail space.[202]

Notable people

Hartford has been home to many historically significant people, such as dictionary author Noah Webster (1758–1843), inventor Sam Colt (1814–62), and American financier and industrialist J.P. Morgan (1837–1913).[203][204][205]

Some of America's most famous authors lived in Hartford, including Mark Twain (1835–1910), who moved to the city in 1874. Twain's next-door neighbor at Nook Farm was Harriet Beecher Stowe (1811–96). Poet Wallace Stevens (1879–1955) was an insurance executive in the city, and World War II correspondent Lyn Crost (1915–97) lived there.[206][207][208][209] More recently, Dominick Dunne (1925–2009), John Gregory Dunne (1932–2003), and Suzanne Collins (born 1962) have resided in Hartford.[210][211][212]

Actors and others in the entertainment business from Hartford include Academy Award–winning film icon Katharine Hepburn, actors Gary Merrill, Linda Evans, Eriq La Salle, Diane Venora, William Gillette, and Charles Nelson Reilly, and TV producer and writer Norman Lear. Marvel Comics artist George Tuska grew up in Hartford.[213]

Barbara McClintock (1902-1992), pioneering cytogeneticist was born in Hartford, CT. She was awarded the 1983 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for the breakthrough discovery of genetic transposition. She is the only woman to receive an unshared Nobel Prize in the Medicine category.

Frederick Law Olmsted (1822 - 1903), considered the father of the profession of Landscape Architecture, among his designs: New York's Central Park, 1901 Chicago World's Fair, and Asheville's Biltmore Estate. Other projects that Olmsted was involved in include the country's first and oldest coordinated system of public parks and parkways in Buffalo, New York; the country's oldest state park, the Niagara Reservation in Niagara Falls, New York; one of the first planned communities in the United States, Riverside, Illinois; Mount Royal Park in Montreal, Quebec; the Emerald Necklace in Boston, Massachusetts; Highland Park in Rochester, New York; Belle Isle Park, in the Detroit River for Detroit, Michigan; the Grand Necklace of Parks in Milwaukee, Wisconsin; Cherokee Park and entire parks and parkway system in Louisville, Kentucky.

In the field of music, natives include singer Sophie Tucker (1884–1966), "last of the red-hot mamas." Others include:

- Rock and Roll Hall of Fame members Gene Pitney and Mike Carabello (of Santana)

- Mark McGrath

- bass guitarist Doug Wimbish of Living Colour

- Cindy Blackman (drummer for Lenny Kravitz)

- jazz alto saxophonist Jackie McLean[214]

- concert violinist Elmar Oliveira (b. 1950)

- brothers Jeff Porcaro, Mike Porcaro, and Steve Porcaro (of the group Toto)

Former Cleveland Browns head coach Eric Mangini is from Hartford. Former NHL player Craig Janney and current player Nick Bonino were born in Hartford. Other sports stars include NBA players Marcus Camby, Rick Mahorn, Johnny Egan, and Michael Adams, as well as NFL kicker John Carney, Dwight Freeney, Tebucky Jones, and Eugene Robinson.[215]

Sister cities

Hartford features numerous sister cities.[216] They include:

-

Afula, Israel

Afula, Israel -

Bydgoszcz, Poland

Bydgoszcz, Poland -

Caguas, Puerto Rico

Caguas, Puerto Rico -

Dongguan, Guangdong, China

Dongguan, Guangdong, China -

Floridia, Italy

Floridia, Italy -

Freetown, Sierra Leone

Freetown, Sierra Leone -

Hertford, Hertfordshire, United Kingdom

Hertford, Hertfordshire, United Kingdom -

João Pessoa, Brazil

João Pessoa, Brazil -

Mangualde, Portugal

Mangualde, Portugal -

Morant Bay, Jamaica

Morant Bay, Jamaica -

New Ross, Ireland

New Ross, Ireland -

Ocotal, Nicaragua

Ocotal, Nicaragua -

Thessaloniki, Greece

Thessaloniki, Greece

See also

Notes

- ↑ Mean monthly maxima and minima (i.e. the expected highest and lowest temperature readings at any point during the year or given month) calculated based on data at said location from 1981 to 2010.

- ↑ Official records for Hartford kept at downtown from January 1905 to December 1948, Brainard Airport from January 1949 to December 1954, and at Bradley Int'l in Windsor Locks since January 1955.[57]

References

- 1 2 "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved June 9, 2017.

- ↑ http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/cph-2-8.pdf Connecticut: 2010 Population and Housing Unit Counts, U.S. Census Bureau, June 2012, table 8, page 11. Retrieved May 17, 2014

- ↑ City of Hartford History (The State of Connecticut is sometimes known as "the land of steady habits.")Connecticut Nicknames, Connecticut State Library Archived February 5, 2006, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Paul Zielbauer, "Poverty in a Land of Plenty: Can Hartford Ever Recover?" The New York Times, August 26, 2002.

- ↑ "Metro Hartford Progress Points, retrieved 3/13/2015" (PDF). Archived from the original on 2014-07-06.

- ↑ Bacon, Nick. 2013. "Podunk after Pratt: Place and Placelessness in East Hartford, CT." Pp. 46–64 in Confronting Urban Legacy: Rediscovering Hartford and New England's Forgotten Cities. Xiangming Chen and Nick Bacon (eds). Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

- ↑ Sterner, Daniel (2012). A Guide to Historic Hartford, Connecticut. The History Press. p. 81. ISBN 1-60949-635-3. Retrieved 16 August 2014.

- ↑ "House of Hope". The New Netherland Institute. The New Netherland Institute. Retrieved 5 April 2015.

- ↑ Scaeva (1853). Hartford in the Olden Time, Its First Thirty Years (1st ed.). Hartford: F.A. Brown. pp. 25–36.

- ↑ Walsh, Andrew. "Hartford: A Global History." Pp. 21–45 in Confronting Urban Legacy: Rediscovering Hartford and New England's Forgotten Cities. Xiangming Chen and Nick Bacon (eds.). Lanham, MD: Lexington Books

- ↑ Shuffelton, Frank (1977). Thomas Hooker, 1586–1647. Princeton University Press. p. 212. ISBN 978-0-691-61327-7. Retrieved 5 April 2015.

- ↑ "Seal of the City of Hartford (higher resolution image)".

- ↑ Voigt, Steven. "Lessons from Thomas Hooker about the frailty of humanity and the importance of a worldview". Renew America. Archived from the original on October 31, 2005. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- ↑ "The Charter Oak Fell – Today in History: August 21". connecticuthistory.org. Connecticut Humanities. Retrieved 16 August 2014.

- ↑ Lamb, David (15 June 2003). "Once-Gilded City Buffing Itself Up". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

- ↑ "Hartford Convention | United States history". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2017-04-30.

- ↑ "God In America - People - Lyman Beecher". God in America. Retrieved 2017-04-30.

- ↑ "Lyman Beecher - Ohio History Central". www.ohiohistorycentral.org. Retrieved 2017-04-30.

- ↑ "Harriet B. Stowe - Ohio History Central". www.ohiohistorycentral.org. Retrieved 2017-04-30.

- ↑ "Harriet Beecher Stowe's Life". www.harrietbeecherstowecenter.org. Retrieved 2017-04-30.

- ↑ "Education & Resources - National Women's History Museum - NWHM". www.nwhm.org. Retrieved 2017-04-30.

- ↑ "Hartford Wide-Awakes – Today in History: July 26 | ConnecticutHistory.org". connecticuthistory.org. Retrieved 2017-04-30.

- ↑ Spencer, Luke (7 May 2015). "Coltsville, USA: Inside America's Gun-Funded Utopia". Atlas Obscura. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

- ↑ Smith, Anthony (2 November 2004). Machine Gun: The Story of the Men and the Weapon That Changed the Face of War. St. Martin's Press. pp. 52–53. ISBN 978-0-312-93477-4.

- ↑ Lehto, Mark R.; Buck, James R. (2008). Introduction to Human Factors and Ergonomics for Engineers. New York: Taylor & Francis. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-8058-5308-7.

- ↑ Grant, Ellsworth S. (1982). The Colt legacy: the Colt Armory in Hartford, 1855–1980. Mowbray Co. pp. 22, 58. ISBN 978-0-917218-17-0.

- ↑ Hosley, William. "Making a Success of Coltsville". hogriver.org. Hog River Journal. Retrieved 16 August 2014.

- ↑ Editorial Staff (11 July 2014). "Sam Colt's 200th Birthday". Hartford Courant. Retrieved 16 August 2014.

- ↑ "Church of the Good Shepherd and Parish House" (pdf). Retrieved 16 August 2014.

- ↑ "Elizabeth Hart Jarvis Colt". Connecticut Women's Hall of Fam. 2012. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

- ↑ Hartford Parks Department. "Colt Park and Dillon Stadium". hartford.gov. City of Hartford. Retrieved 16 August 2014.

- ↑ Clymer, Floyd. Treasury of Early American Automobiles, 1877–1925 (New York: Bonanza Books, 1950), p.37.

- ↑ Hintz, Eric (6 June 2012). "Samuel Colt ... and Sewing Machines?". O, Say Can You See Blog. National Museum of American History. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

- 1 2 Flayderman, Norm (2007). Flayderman's Guide to Antique American Firearms and Their Values. Iola, Wisconsin: F+W Media, Inc. pp. 193–196. ISBN 0-89689-455-X.

- ↑ "Invention hot spot: Beginnings of mass production in 19th-century Hartford, Connecticut". invention.smithsonian.org. Jerome and Dorothy Lemelson Center for the Study of Invention and Innovation, Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on 19 August 2014. Retrieved 15 August 2014.

- ↑ Goddard, Stephen B. (December 30, 2008). Colonel Albert Pope and His American Dream Machines: The Life and Times of a Bicycle Tycoon Turned Automotive Pioneer. McFarland. pp. 176–182. ISBN 0-7864-4089-9.

- ↑ Hamilton, Robert A. (1992-04-12). "116-Year-Old Company Thrives on Innovation". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2017-04-30.

- ↑ "Record-Breaking Flood at Hartford, Conn.". Popular Mechanics. June 1909. Retrieved 4 February 2009.

- ↑ "Hartford Circus Fire: "The Tent's on Fire!" – Who Knew? | ConnecticutHistory.org". connecticuthistory.org. Retrieved 2017-04-30.

- ↑ Cruz, Jose. "A Decade of Change: Putero Rican Politics in Hartford Connecticut" (PDF). trincoll.edu. Retrieved 2017-04-29.

- ↑ "The "Four Builds" – The History of Hartford, Connecticut - Connecticut Historical Society". Connecticut Historical Society. 2014-12-16. Retrieved 2017-04-30.

- ↑ "Developer proposes new arena in Hartford" AP report on ESPN.com (December 29, 2005)

- ↑ The estimated population as of 2008 is 124,062 – an increase of 2,484 from the 2000 Census. US Census: Population Finder: hartford city, CT

- ↑ "I Dream a World: Portraits of Black Women Who Changed America" by Brian Lanker Archived March 20, 2012, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ HAMAD, MICHAEL. "Four Days Of Hip Hop At Trinity International Fest". courant.com. Retrieved 2017-04-30.

- ↑ CARLESSO, JENNA. "Hartford Hires Bankruptcy Lawyer As City Officials Weigh Options". Courant Community. Retrieved 2017-07-09.

- ↑ "Law Firm to Help Hartford Evaluate Restructuring Efforts". NBC Connecticut. Retrieved 2017-07-09.

- ↑ Office, Enter your Company or Top-Level. "DECD: DECD:Connecticut Population, Land Area, and Density by Location". www.ct.gov. Retrieved 2017-04-30.

- ↑ "Population per square mile, 2010". www.census.gov. Retrieved 2017-04-30.

- ↑ GRANT, STEVE. "Hartford: A City On The River". courant.com. Retrieved 2017-04-30.

- ↑ Archived June 22, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Main Street Bridge". Past-inc.org. Retrieved 2012-06-09.

- ↑ "USDA Plant Hardiness Zone Map". planthardiness.ars.usda.gov. Retrieved 2017-05-19.

- ↑ Team, National Weather Service Corporate Image Web. "National Weather Service Climate". w2.weather.gov. Retrieved 2017-05-19.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2016-04-17.

- ↑ "The Winter of 95–96: A Season of Extremes, National Climatic Data Center" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-06-09.

- ↑ ThreadEx

- ↑ "Station Name: CT HARTFORD BRADLEY INTL AP". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2014-03-13.

- ↑ "WMO Climate Normals for HARTFORD/BRADLEY INT'L ARPT CT 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2014-03-11.

- ↑

- ↑ "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ↑ Hartford (city) QuickFacts from the US Census Bureau Archived 2012-06-18 at WebCite. Quickfacts.census.gov. Retrieved on 2013-07-15.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Hartford (city), Connecticut". State & County QuickFacts. U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 2012-06-18.

- ↑ "Race and Hispanic Origin for Selected Cities and Other Places: Earliest Census to 1990". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 2012-08-06.

- ↑ Sacks, Michael Paul (2011-05-01). "The Puerto Rican effect on Hispanic residential segregation: A study of the Hartford and Springfield metro areas in national perspective". Latino Studies. 9 (1): 87–105. ISSN 1476-3435. doi:10.1057/lst.2011.1.

- ↑ RODRÍGUEZ, FÉLIX; MATOS, V. (2013-12-09). "Puerto Ricans in the United States: Past, Present and Future" (PDF). Eastern Regional Conference. Retrieved 2017-05-29.