Harrowing of Hell

_Cropped.jpg)

In Christian theology, the Harrowing of Hell (Latin: Descensus Christi ad Inferos, "the descent of Christ into hell") is the triumphant descent of Christ into Hell (or Hades) between the time of his Crucifixion and his Resurrection when he brought salvation to all of the righteous who had died since the beginning of the world (excluding the damned).[1] After his death, the soul of Jesus was supposed to have descended into the realm of the dead, which the Apostles' Creed calls "hell" in the old English usage. The realm into which Jesus descended is called Sheol or Limbo by some Christian theologians to distinguish it from the hell of the damned.[2]

The Harrowing of Hell is referred to in the Apostles' Creed and the Athanasian Creed (Quicumque vult) which state that Jesus Christ "descended into Hell". Christ having descended to the underworld is alluded to in the New Testament in 1 Peter 3:19–20, which speaks of Jesus preaching to "the imprisoned spirits". (The Catholic Catechism interprets Ephesians 4:9, which states that "[Christ] descended into the lower parts of the earth", as also supporting this interpretation.)[3] This near-absence in Scripture has given rise to controversy and differing interpretations.[4]

According to The Catholic Encyclopedia, the story first appears clearly in the Gospel of Nicodemus in the section called the Acts of Pilate, which also appears separately at earlier dates within the Acts of Peter and Paul.[5] The descent into hell had been related in Old English poems connected with the names of Cædmon and Cynewulf. It is subsequently repeated in Aelfric's homilies c. 1000 AD, which is the first known inclusion of the word "harrowing". Middle English dramatic literature contains the fullest and most dramatic development of the subject.[1]

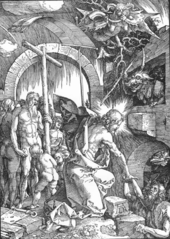

As an image in Christian art, the harrowing is also known as the Anastasis (a Greek word for "resurrection"), considered a creation of Byzantine culture and first appearing in the West in the early 8th century.[6]

Terminology

The Greek wording in the Apostles' Creed is κατελθόντα εἰς τὰ κατώτατα, ("katelthonta eis ta katôtata"), and in Latin descendit ad inferos. The Greek τὰ κατώτατα (ta katôtata,"the lowest") and the Latin inferos ("those below") may also be translated as "underworld", "netherworld", or "abode of the dead."

The word "harrow" comes from the Old English hergian meaning to harry or despoil and is seen in the homilies of Aelfric, c. 1000.[7] The term Harrowing of Hell refers not merely to the idea that Christ descended into Hell, as in the Creed, but to the rich tradition that developed later, asserting that he triumphed over inferos, releasing Hell's captives, particularly Adam and Eve, and the righteous men and women of the Old Testament period.

Sources

Scripture

In Classical mythology Hades is the underworld inhabited by departed souls and the god Pluto is its ruler. The New Testament uses the term "Hades" to refer to the abode or state of the dead. In some places it seems to represent a neutral place where the dead awaited the death, burial, and resurrection of Jesus. Several passages from the New Testament have been taken by some to imply that Christ descended into this realm of the dead to bring the righteous ones to Heaven. Other New Testament passages imply it is a place of torment for the unrighteous, leading to speculation that it may be divided into two very different sections.

Verses containing the word "Hades"

In the New King James version of the New Testament, there are 11 references to Hades:

- Matthew 11:23: "And you, Capernaum, who are exalted to heaven, will be brought down to Hades; for if the mighty works which were done in you had been done in Sodom, it would have remained until this day."

- Matthew 12:40 Without using the word "Hades", it may be implicit here: "For as Jonah was three days and three nights in the belly of the great fish, so will the Son of Man be three days and three nights in the heart of the earth.

- Matthew 16:18: "And I also say to you that you are Peter, and on this rock I will build My church, and the gates of Hades shall not prevail against it."

- Luke 10:15: "And you, Capernaum, who are exalted to heaven, will be brought down to Hades."

- Luke 16:23: "And being in torments in Hades, he lifted up his eyes and saw Abraham afar off, and Lazarus in his bosom. (See article Abraham's bosom)

- Acts 2:27: "For You will not leave my soul in Hades, nor will You allow Your Holy One to see corruption.

- Acts 2:31: "...he, foreseeing this, spoke concerning the resurrection of the Christ, that His soul was not left in Hades, nor did His flesh see corruption."

- 1 Corinthians 15:55: “O Death, where is your sting? O Hades, where is your victory?”

- Revelation 1:18: "I am He who lives, and was dead, and behold, I am alive forevermore. Amen. And I have the keys of Hades and of Death."

- Revelation 6:8: "So I looked, and behold, a pale horse. And the name of him who sat on it was Death, and Hades followed with him. And power was given to them over a fourth of the earth, to kill with sword, with hunger, with death, and by the beasts of the earth."

- Revelation 20:13: "The sea gave up the dead who were in it, and Death and Hades delivered up the dead who were in them. And they were judged, each one according to his works."

- Revelation 20:14: "Then Death and Hades were cast into the lake of fire. This is the second death."

Verses without "Hades" but doctrinal support

Although these verses do not contain the word "Hades", theologians have concluded that comparable terms are used as synonyms:

- 1 Peter 3:19–20: (Jesus) "went and made proclamation to the imprisoned spirits—to those who were disobedient long ago when God waited patiently in the days of Noah while the ark was being built. In it only a few people, eight in all, were saved through water...."

- In the original Greek: "ἐν ᾧ καὶ τοῖς ἐν φυλακῇ πνεύμασιν πορευθεὶς ἐκήρυξεν, ἀπειθήσασίν ποτε ὅτε ἀπεξεδέχετο ἡ τοῦ θεοῦ μακροθυμία ἐν ἡμέραις Νῶε…."

- 1 Peter 4:6: "For this reason the gospel was preached also to those who are dead, that they might be judged according to men in the flesh, but live according to God in the spirit."

- In the original Greek: "εἰς τοῦτο γὰρ καὶ νεκροῖς εὐηγγελίσθη…")

- Ephesians 4:7-10 NIV: "But to each one of us grace has been given as Christ apportioned it. This is why it[or God] says, 'When he ascended on high, he took many captives and gave gifts to his people.'[Psalm 68:18] (What does 'he ascended' mean except that he also descended to the lower, earthly regions?[or the depths of the earth] He who descended is the very one who ascended higher than all the heavens, in order to fill the whole universe."

- In the original Greek: διὸ λέγει, ἀναβὰς εἰς ὕψος ᾐχμαλώτευσεν αἰχμαλωσίαν, ἔδωκεν δόματα τοῖς ἀνθρώποις. τὸ δὲ ἀνέβη τί ἐστιν εἰ μὴ ὅτι καὶ κατέβη εἰς τὰ κατώτερα [μέρη] τῆς γῆς; ὁ καταβὰς αὐτός ἐστιν καὶ ὁ ἀναβὰς ὑπεράνω πάντων τῶν οὐρανῶν, ἵνα πληρώσῃ τὰ πάντα.

- Verse 8 above is a truncated paraphrase adapting Psalm 68:18, with a changed point of view: "When you ascended on high, you led captives in your train; you received gifts from men, even from the rebellious—that you, O LORD God, might dwell there."(NIV) The parenthetical verses 9–10 of Ephesians are widely read as an exegetical gloss on the text. The word for "lower parts" (the comparative form: τὰ κατώτερα) is similar to the word used for "Hell" in the Greek version of the Apostles Creed (the superlative form: τὰ κατώτατα, English: "lowest [places]").

- Frank Stagg writes that the entire passage Ephesians 4:1-16 is a prayerful exhortation to the readers that they measure up to their high calling in Christ. He takes "measuring up" to mean in terms of the unity and maturity of the one body which they already are (vv. 4,12,16). He says that in this long paragraph, the goal of redemption is the building up of the one body of Christ. Verses 4 through 6 set forth their sevenfold unity: "one body, one Spirit, ...one hope..., one Lord, one faith, one baptism, one God and Father of all, the one over all and through all, and in all." Without mentioning "harrowing", he writes that "The very Christ who ascended is then described as the one who descended and who gave the apostles, the prophets, the evangelists, the pastors, and teachers to the church.[8]:p.195

- Philippians 2:9-10: "God exalted Him and gave to Him the name that is above every name, so that at the name of Jesus, every knee should bend, of those in heaven, and on the earth, and under the earth" (Emphasis added).

- This can also refer to the power of Jesus over Satan. The passage is poetic, and so need not mean that Sheol is under the earth.[2]

- Romans 10:6-8: "But the righteousness which is of faith speaketh on this wise, Say not in thine heart, Who shall ascend into heaven? (that is, to bring Christ down from above:) Or, Who shall descend into the deep? (that is, to bring up Christ again from the dead.) But what saith it? The word is nigh thee, even in thy mouth, and in thy heart: that is, the word of faith, which we preach;" refers to descending into the deep (the abyss) and this is contrasted with ascending into heaven.

- These verses speak of the work of Christ as Himself having done all that is necessary, descending to the deep and ascending into heaven, being complete and sufficient for all who believe in Him. This salvation can therefore be received by faith in the word preached, without the need for persons to achieve it for themselves.

- Zechariah 9:11 refers to prisoners in a waterless pit. "As for you, because of the blood of my covenant with you, I will free your prisoners from the waterless pit."

- The verses' reference to captives has been presented as a reflection of Yahweh's captives of the enemy in Psalm 68:17–18: "God's chariots were myriad, thousands upon thousands; from Sinai the Lord entered the holy place. You went up to its lofty height; you took captives, received slaves as tribute. No rebels can live in the presence of God."

- Isaiah 24:21-22 also refers to spirits in prison, reminiscent of Peter's account of a visitation to spirits in prison: "And it shall come to pass in that day, that the LORD shall punish the host of the high ones that are on high, and the kings of the earth upon the earth. And they shall be gathered together, as prisoners are gathered in the pit, and shall be shut up in the prison, and after many days shall they be visited."

Early Christian teaching

The Harrowing of Hell was taught by theologians of the early church: St Melito of Sardis (died c. 180) Homily on the Passion; Tertullian (A Treatise on the Soul, 55), Hippolytus (Treatise on Christ and Anti-Christ) Origen (Against Celsus, 2:43), and, later, St Ambrose (died 397) all wrote of the Harrowing of Hell. The early heretic Marcion and his followers also discussed the Harrowing of Hell, as mentioned by Tertullian, Irenaeus, and Epiphanius.

The Gospel of Matthew relates that immediately after Christ died, the earth shook, there was darkness, the veil in the Temple was torn in two, and many people rose from the dead and walked about in Jerusalem and were seen by many people there. According to the apocryphal Gospel of Nicodemus, the Harrowing of Hell was foreshadowed by Christ's raising of Lazarus from the dead prior to his own crucifixion. The hymns proper to the weekend suggest that as he did on earth, John the Baptist prepared the way for Jesus in Hell by prophesying to the spirits held there that Christ would soon save them.

In the Acts of Pilate—usually incorporated with the widely read medieval Gospel of Nicodemus—texts built around an original that might have been as old as the 3rd century AD with many improvements and embroidered interpolations, chapters 17 to 27 are called the Decensus Christi ad Inferos. They contain a dramatic dialogue between Hades and prince Satan, and the entry of the King of Glory, imagined as from within Tartarus.

The richest, most circumstantial accounts of the Harrowing of Hell are found in medieval dramatic literature, such as the four great cycles of English mystery plays which each devote a separate scene to depict it, or in passing references in Dante's Inferno. The subject is found also in the Cornish mystery plays and the York and Wakefield cycles. These medieval versions of the story do not derive from the bare suggestion made in the Epistle ascribed to Peter, but come from the Gospel of Nicodemus.[9]

Conceptions of the afterlife

The Old Testament view of the afterlife was that all people, whether righteous or unrighteous, went to Sheol when they died. No Hebrew figure ever descended into Sheol and returned, although an apparition of the recently deceased Samuel briefly appeared to Saul when summoned by the Witch of Endor. Several works from the Second Temple period elaborate the concept of Sheol, dividing it into sections based on the righteousness or unrighteousness of those who have died.

The New Testament maintains a distinction between Sheol, the common "place of the dead", and the eternal destiny of those condemned at the Final Judgment, variously described as Gehenna, "the outer darkness," or a lake of eternal fire. Modern English translations of the Bible maintain this distinction (e.g. by translating Sheol as "the Pit" and Gehenna as "Hell"), but the influential King James Version used the word "hell" to translate both concepts.

The Hellenistic views of heroic descent into the Underworld and successful return follow traditions that are far older than the mystery religions popular at the time of Christ. The Epic of Gilgamesh includes such a scene, and it appears also in Odyssey XI. Writing shortly before the birth of Jesus, Vergil included it in the Aeneid. What little we know of the worship in mystery religions such as the Eleusinian Mysteries and Mithraism suggests that a ritual death and rebirth of the initiate was an important part of their liturgy. Again, this has earlier parallels, in particular with the worship of Osiris. The ancient homily on The Lord's Descent into Hell may mirror these traditions by referring to baptism as a symbolic death and rebirth. (cf. Colossians 2:9–15) Or, these traditions of Mithraism may be drawn from early Christian homilies.

Interpretations of the doctrine

Catholic

There is an ancient homily on the subject, of unknown authorship, usually entitled The Lord's Descent into Hell that is the second reading at Office of Readings on Holy Saturday in the Catholic Church.[10]

The Catechism of the Catholic Church states: "By the expression 'He descended into Hell', the Apostles' Creed confesses that Jesus did really die and through his death for us conquered death and the devil 'who has the power of death' (Hebrews 2:14). In his human soul united to his divine person, the dead Christ went down to the realm of the dead. He opened Heaven's gates for the just who had gone before him."[11]

As the Catechism says, the word "Hell"—from the Norse, Hel; in Latin, infernus, infernum, inferi; in Greek, ᾍδης (Hades); in Hebrew, שאול (Sheol)—is used in Scripture and the Apostles' Creed to refer to the abode of all the dead, whether righteous or evil, unless or until they are admitted to Heaven (CCC 633). This abode of the dead is the "Hell" into which the Creed says Christ descended. His death freed from exclusion from Heaven the just who had gone before him: "It is precisely these holy souls who awaited their Savior in Abraham's bosom whom Christ the Lord delivered when he descended into Hell", the Catechism states (CCC 633), echoing the words of the Roman Catechism, 1,6,3. His death was of no avail to the damned.

Conceptualization of the abode of the dead as a place, though possible and customary, is not obligatory (Church documents, such as catechisms, speak of a "state or place"). Some maintain that Christ did not go to the place of the damned, which is what is generally understood today by the word "Hell". For instance, Thomas Aquinas taught that Christ did not descend into the "Hell of the lost" in his essence, but only by the effect of his death, through which "he put them to shame for their unbelief and wickedness: but to them who were detained in Purgatory he gave hope of attaining to glory: while upon the holy Fathers detained in Hell solely on account of original sin, he shed the light of glory everlasting."[12]

While some maintain that Christ merely descended into the "limbo of the fathers", others, notably theologian Hans Urs von Balthasar (inspired by the visions of Adrienne von Speyr), maintain that it was more than this and that the descent involved suffering by Jesus.[13] Some maintain that this is a matter on which differences and theological speculation are permissible without transgressing the limits of orthodoxy.[13] However, Balthasar's point here has been forcefully condemned by conservative Catholic outlets.[14][15]

Eastern Orthodox

Saint John Chrysostom's Paschal Homily also addresses the Harrowing of Hades, and is typically read during the Paschal Vigil, the major service of the Eastern Orthodox celebration of Pascha (Easter).

In the Eastern Orthodox Church, the Harrowing of Hades is celebrated annually on Holy and Great Saturday, during the Vesperal Divine Liturgy of Saint Basil. At the beginning of the service, the hangings in the church and the vestments worn by the clergy are all somber Lenten colours (usually purple or black). Then, just before the Gospel reading, the liturgical colors are changed white and the deacon performs a censing, and the priest strews laurel leaves around the church, symbolizing the broken gates of hell; this is done in celebration of the harrowing of Hades then taking place, and in anticipation of Christ's imminent resurrection.

The Harrowing of Hades is generally more common and prominent in Orthodox iconography compared to the Western tradition. It is the traditional icon for Holy Saturday, and is used during the Paschal season and on Sundays throughout the year.

The traditional Eastern Orthodox icon of the Resurrection of Jesus does not depict simply the physical act of Jesus's coming out of the Tomb, but rather it depicts what Orthodox Christians believe to be the spiritual reality of what his Death and Resurrection accomplished.

The icon shows Jesus, vested in white and gold to symbolize his divine majesty, standing on the brazen gates of Hades (also called the "Doors of Death"), which are broken and have fallen in the form of a cross, illustrating the belief that by his death on the cross, Jesus trampled down death (see Paschal troparion). He is holding Adam and Eve and pulling them up out of Hades. Traditionally, he is not shown holding them by the hands, but by their wrists, to illustrate the theological teaching that mankind could not pull himself out of his ancestral sin, but that it could come about only by the work (energia) of God. Jesus is surrounded by various righteous figures from the Old Testament (Abraham, David, etc.); the bottom of the icon depicts Hades as a chasm of darkness, often with various pieces of broken locks and chains strewn about. Quite frequently, one or two figures are shown in the darkness, bound in chains, who are generally identified as personifications of Death and/or the Devil.

Lutheran

Martin Luther, in a sermon delivered in Torgau in 1533, stated that Christ descended into Hell.

The Formula of Concord (a Lutheran confession) states, "we believe simply that the entire person, God and human being, descended to Hell after his burial, conquered the devil, destroyed the power of Hell, and took from the devil all his power." (Solid Declaration, Art. IX)

Many attempts were made following Luther's death to systematize his theology of the descensus, whether Christ descended in victory or humiliation. For Luther, however, the defeat or "humiliation" of Christ is never fully separable from His victorious glorification. Some argued that Christ's suffering was completed with His words from the cross, "It is finished." Luther himself, when pressed to elaborate on the question of whether Christ descended to Hell in humiliation or victory responded, "It is enough to preach the article to the laypeople as they have learned to know it in the past from the stained glass and other sources."

Calvinist

John Calvin expressed his concern that many Christians "have never earnestly considered what it is or means that we have been redeemed from God's judgment. Yet this is our wisdom: duly to feel how much our salvation cost the Son of God." Calvin's conclusion is that "Christ's descent into Hell was necessary for Christians' atonement, because Christ did in fact endure the penalty for the sins of the redeemed."[16] Calvin strongly opposed the notion that Christ freed prisoners, as opposed to traveling to Hell as part of completing his sufferings (Institutes of the Christian Religion, Book 2, chapter 16, sections 8-10),

The Reformed interpret the phrase "he descended into Hell" as referring to Christ's pain and humiliation prior to his death, and that this humiliation had a spiritual dimension as part of God's judgement upon the sin which he bore on behalf of Christians. The doctrine of Christ's humiliation is also meant to assure believers that Christ has redeemed them from the pain and suffering of God's judgment on sin.[17]

Latter-day Saints

The Harrowing of Hell has been a unique and important doctrine among members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints since its founding in 1830 by Joseph Smith, although members of the church ("Mormons") usually call it by other terms, such as "Christ's visit to the spirit world." Like Christian exegetes distinguishing between Sheol and Gehenna, Latter-day Saints distinguish between the realm of departed spirits (the "spirit world") and the portion (or state) of the wicked ("spirit prison"). The portion or state of the righteous is often referred to as "paradise".

Perhaps the most notable aspect of Latter-day Saint beliefs regarding the Harrowing of Hell is their view on the purpose of it, both for the just and the wicked. Joseph F. Smith, the sixth president of the Church, explained in what is now a canonized revelation, that when Christ died, "there were gathered together in one place an innumerable company of the spirits of the just, ... rejoicing together because the day of their deliverance was at hand. They were assembled awaiting the advent of the Son of God into the spirit world, to declare their redemption from the bands of death" (D&C 138:12,15-16).

In the Latter-day Saint view, while Christ announced freedom from physical death to the just, he had another purpose in descending to Hell regarding the wicked. "The Lord went not in person among the wicked and the disobedient who had rejected the truth, to teach them; but behold, from among the righteous, he organized his forces…and commissioned them to go forth and carry the light of the gospel to them that were in darkness, even to all the spirits of men; and thus was the gospel preached to the dead ... to those who had died in their sins, without a knowledge of the truth, or in transgression, having rejected the prophets" (D&C 138:29-30,32). From the Latter-day Saint viewpoint, the rescue of spirits was not a one-time event but an ongoing process that still continues (D&C 138; 1 Peter 4:6). This concept goes hand-in-hand with the doctrine of baptism for the dead, which is based on the LDS belief that those who choose to accept the gospel in the spirit world must still receive the saving ordinances in order to dwell in the kingdom of God (Mark 16:16; John 3:5; 1 Peter 3:21). These baptisms and other ordinances are performed in LDS temples, wherein a church member is baptized vicariously, or in behalf of, those who died without being baptized by proper authority. The recipients in the spirit world then have the opportunity to accept or reject this baptism.[18]

Rejection of the doctrine

A number of Christians reject the doctrine of the "harrowing of hell", claiming that "there is scant scriptural evidence for [it], and that Jesus's own words contradict it".[19] John Piper, for example, says "there is no textual [i.e. Biblical] basis for believing that Christ descended into hell", and, therefore, Piper does not recite the "he descended into hell" phrase when saying the Apostles' Creed.[20] Wayne Grudem also skips the phrase when reciting the Creed; he says that the "single argument in ... favor [of the "harrowing of hell" clause in the Creed] seems to be that it has been around so long. ... But an old mistake is still a mistake".[19] In his book Raised with Christ, Pentecostal Adrian Warnock agrees with Grudem, commenting, "Despite some translations of an ancient creed [i.e. the Apostles' Creed], which suggest that Jesus ... 'descended into hell', there is no biblical evidence to suggest that he actually did so."[21]

Augustine (354–430) argued that 1 Peter 3:19–20, the chief passage used to support the doctrine of the "harrowing of hell", is "more allegory than history".[19]

Christian mortalism

The above views share the traditional Christian belief in the immortality of the soul. The mortalist view of the intermediate state requires an alternative view of the Acts 2:27 and Acts 2:31, taking a view of the New Testament use of Hell as equivalent to use of Hades in the Septuagint and therefore to Sheol in the Old Testament.[22] William Tyndale and Martin Bucer of Strassburg argued that Hades in Acts 2 was merely a metaphor for the grave. Other reformers Christopher Carlisle and Walter Deloenus in London, argued for the article to be dropped from the creed.[23] The Harrowing of Hell was a major scene in traditional depictions of Christ's life avoided by John Milton due to his mortalist views.[24] Mortalist interpretations of the Acts 2 statements of Christ being in Hades are also found among later Anglicans such as E. W. Bullinger.[25]

While those holding mortalist views on the soul would agree on the "harrowing of hell" concerning souls, that there were no conscious dead for Christ to literally visit, the question of whether Christ himself was also dead, unconscious, brings different answers:

- To most Protestant advocates of "soul sleep" such as Martin Luther, Christ himself was not in the same condition as the dead, and while his body was in Hades, Christ, as second person of the Trinity, was conscious in heaven.[26]

- To Christian mortalists who are also non-Trinitarian, such as Socinians and Christadelphians,[27] the maxim "the dead know nothing" includes also Christ during the three days.

Of the three days, Christ says "I was dead" (Greek egenomen nekros ἐγενόμην νεκρὸς, Latin fui mortuus).[Revelation 1:18]

In culture

Drama

- The earliest surviving Christian drama probably intended to be performed is the Harrowing of Hell found in the 8th-century Book of Cerne.

Literature

- In Dante's Inferno the Harrowing of Hell is mentioned in Canto IV by the pilgrim's guide Virgil. Virgil was in Hell in the first place because he was not exposed to Christianity in his lifetime, and therefore he actually describes in generic terms Christ as a "mighty one" who rescued the Hebrew forefathers of Christianity, but left him behind in the very same circle. It is clear that he does not fully understand the significance of the event, as Dante does.

- An incomplete Middle English telling of the Harrowing of Hell is found in the Auchinleck manuscript.[28]

- Although the Orfeo legend has its origin in pagan antiquity, the Medieval romance of Sir Orfeo has often been intrepreted as drawing parallels between the Greek hero and Jesus freeing souls from Hell,[29][30] with the explication of Orpheus' descent and return from the underworld as an allegory for Christ's as early as the Ovide Moralisé (1340).[31]

- In Stephen Lawhead's novel Byzantium (1997), a young Irish monk is asked to explain Jesus' life to a group of Vikings, who were particularly impressed with Jesus' "Descent to the underworld" (Helreið).

Parallels in Jewish literature reference legends of Enoch and Abraham's harrowings of the underworld, unrelated to Christian themes. These have been updated in Isaac Leib Peretz's short story "Neilah in Gehenna", in which a Jewish hazzan descends to Hell and uses his unique voice to bring about the repentance and liberation of the souls imprisoned there.

Music

- The Harrowing of Hell is the subject of several baroque oratorios, most notably Salieri's Gesù al Limbo (1803) to a text by Luigi Prividali.[32]

Art

- A follower of Hieronymus Bosch depicts Christ in Limbo in a vivid composition, now owned by the Indianapolis Museum of Art[33]

See also

References

- 1 2 Warren, Kate Mary. "Harrowing of Hell." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 7. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1910.3 Mar. 2013 Notice that the Latin word is inferos NOT infernos. Inferos meaning below, infernos meaning flames of fire.<http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/07143d.htm>.

- 1 2 Most, William G. "Christ's Descent into Hell and His Resurrection".<http://www.ewtn.com/faith/teachings/resua1.htm> Accessed 7 Mar 2013

- ↑ http://www.vatican.va/archive/ccc_css/archive/catechism/p122a5p1.htm%7C Section 631

- ↑ D. Bruce Lockerbie, The Apostle's Creed: Do You Really Believe It (Victor Books, Wheaton, IL) 1977:53–54, on-line text.

- ↑ New Testament Apocrypha, Vol. 1 by Wilhelm Schneemelcher and R. Mcl. Wilson (Dec 1, 1990) ISBN 066422721X pages 501-502

- ↑ Leslie Ross, entry on "Anastasis", Medieval Art: A Topical Dictionary (Greenwood, 1996), pp. 10–11 online.

- ↑ Harrow is a by-form of harry, a military term meaning to "make predatory raids or incursions"OED

- ↑ Stagg, Frank. New Testament Theology. Nashville: Broadman, 1962. ISBN 0-8054-1613-7

- ↑ "The Apocryphal New Testament" edited by Prof JK Elliott 1993 ISBN 0-19-826182-9 pp164

- ↑ The Lord's descent into hell

- ↑ Catechism of the Catholic Church, p. 636–7.

- ↑ Summa Theologica, III, 52, art. 2

- 1 2 Reno, R.R. Was Balthasar a Heretic? First Things, October 13, 2008

- ↑ "Massa Damnata". ChurchMilitant.TV.

- ↑ Did Christ Suffer in Hell When He Descended into Hell?. Taylor Marshall.

- ↑ Center for Reformed Theology and Apologetics

- ↑ Allen, R. Michael (2012). Reformed Theology. pp. 67–68.

- ↑ "Frequently Asked Questions", Mormon.org, LDS Church

|contribution=ignored (help) - 1 2 3 Daniel Burke, 'What did Jesus do on Holy Saturday?' in The Washington Post, April 2, 2012 (accessed 14/01/2013)

- ↑ John Piper, 'Did Christ Ever Descend to Hell?' in The Christian Post April 23, 2011 (accessed 14/01/2013)

- ↑ Adrian Warnock, Raised with Christ (Wheaton: Crossway, 2010), p. 33-34

- ↑ Norman T. Burns, Christian Mortalism from Tyndale to Milton 1972 p. 180.

- ↑ Descent into Hell in International Standard Bible Encyclopedia: A-D ed. and article Geoffrey W. Bromiley pp. 926-927.

- ↑ William Bridges Hunter Milton's English poetry: being entries from A Milton encyclopedia p. 151.

- ↑ E. W. Bullinger "Hell" in A Critical Lexicon and Concordance to the English and Greek New Testament pp. 367-369.

- ↑ Kenneth Hagen. A theology of Testament in the young Luther: the lectures on Hebrews 1974 p95 "For Luther it refers to God's abandonment of Christ during the three days of his death:"

- ↑ Whittaker H.A. Studies in the Gospels

- ↑ "Auchinleck manuscript". Auchinleck.nls.uk.

- ↑ Henry, Elisabeth (1992). Orpheus with His Lute: Poetry and the Renewal of Life. Bristol Classical Press. pp. 38, 50–53, 81. et passim

- ↑ Treharne, Elaine (2010). "Speaking of the Medieval". The Oxford Handbook of Medieval Literature in English. Oxford University Press. p. 10.

- ↑ Friedman, John Block (2000). Orpheus in the Middle Ages. Syracuse University Press. pp. 125–126.

- ↑ Recording and essay with Il Giudizio Finale; Te Deum. dir Alberto Turco, Bongiovanni

- ↑ "Christ in Limbo". Indianapolis Museum of Art. Retrieved 17 March 2016.

Bibliography

- Trumbower, J. A., "Jesus' Descent to the Underworld," in Idem, Rescue for the Dead: The Posthumous Salvation of Non-Christians in Early Christianity (Oxford, 2001) (Oxford Studies in Historical Theology), 91-108.

- Brinkman, Martien E., "The Descent into Hell and the Phenomenon of Exorcism in the Early Church," in Jerald D. Gort, Henry Jansen and Hendrik M. Vroom (eds), Probing the Depths of Evil and Good: Multireligious Views and Case Studies (Amsterdam/New York, NY, 2007) (Currents of Encounter - Studies on the Contact between Christianity and Other Religions, Beliefs, and Cultures, 33).

- Alyssa Lyra Pitstick, Light in Darkness: Hans Urs von Balthasar and the Catholic Doctrine of Christ's Descent into Hell (Grand Rapids (MI), Eerdmanns, 2007).

- Gavin D'Costa, "Part IV: Christ’s Descent into Hell," in Idem, Christianity and World Religions: Disputed Questions in the Theology of Religions (Oxford, Wiley-Blackwell, 2009),

- Georgia Frank, "Christ’s Descent to the Underworld in Ancient Ritual and Legend," in Robert J. Daly (ed), Apocalyptic Thought in Early Christianity (Grand Rapids (MI), Baker Academic, 2009) (Holy Cross Studies in Patristic Theology and History), 211-226.

- Hilarion Alfayev, Christ the Conqueror of Hell: The Descent into Hades from an Orthodox Perspective. St Vladimirs Seminary Pr (November 20, 2009)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Harrowing of Hell. |

- Catholic Encyclopedia: Harrowing of Hell

- Encyclopædia Britannica: Harrowing of Hell

- Gospel of Nicodemus: Descensus Christ ad inferos

- The Gospel of Nicodemus including the Descent into Hell

- Harrowing of Hell in the Chester Cycle

- Le Harrowing of Hell dans les Cycles de York, Towneley et Chester, by Alexandra Costache-Babcinschi (ebook, French)

- Lord's Descent into Hell, The

- Russian Orthodox iconography of the Harrowing of Hell

- Summa Theologica: Christ's descent into hell