Harper's Weekly

.jpg) Harper's Weekly cover featuring President-Elect Abraham Lincoln; illustration by Winslow Homer from a photograph by Mathew Brady (November 10, 1860) | |

| Illustrators | |

|---|---|

| Categories | News, politics |

| Frequency | Weekly |

| Founder | Fletcher Harper |

| Year founded | 1857 |

| First issue | January 3, 1857 |

| Final issue | May 13, 1916 |

| Company | Harper & Brothers |

| Country | United States |

| Based in | New York City, New York |

| Language | English |

Harper's Weekly, A Journal of Civilization was an American political magazine based in New York City. Published by Harper & Brothers from 1857 until 1916, it featured foreign and domestic news, fiction, essays on many subjects, and humor, alongside illustrations. It carried extensive coverage of the American Civil War, including many illustrations of events from the war. During its most influential period, it was the forum of the political cartoonist Thomas Nast.

History

Inception

.jpg)

Along with his brothers James, John, and Wesley, Fletcher Harper began the publishing company Harper & Brothers in 1825. Following the successful example of the Illustrated London News, Harper started publishing Harper's Magazine in 1850. The monthly publication featured established authors such as Charles Dickens and William Makepeace Thackeray, and within several years, its circulation and interest grew enough to sustain a weekly edition.[1]

In 1857, his company began publishing Harper's Weekly in New York City.[1] By 1860 the circulation of the Weekly had reached 200,000. Illustrations were an important part of the Weekly's content, and it developed a reputation for using some of the most renowned illustrators of the time, notably Winslow Homer, Granville Perkins and Livingston Hopkins.

Among the recurring features were the political cartoons of Thomas Nast, who was recruited in 1862 and worked with the Weekly for more than 20 years. Nast was a feared caricaturist, and is often called the father of American political cartooning.[2] He was the first to use an elephant as the symbol of the Republican Party.[3] He also drew the legendary character of Santa Claus; his version became strongly associated with the figure, who was popularized as part of Christmas customs in the late nineteenth century.

Civil War coverage

Harper's Weekly was the most widely read journal in the United States throughout the period of the Civil War.[4][5] So as not to upset its wide readership in the South, Harper's took a moderate editorial position on the issue of slavery prior to the outbreak of the war. Publications that supported abolition referred to it as "Harper's Weakly". The Weekly had supported the Stephen A. Douglas presidential campaign against Abraham Lincoln, but as the American Civil War broke out, it fully supported Lincoln and the Union. A July 1863 article on the escaped slave Gordon included a photograph of his back, severely scarred from whippings; this provided many readers in the North their first visual evidence of the brutality of slavery. The photograph inspired many free blacks in the North to enlist.[6]

Some of the most important articles and illustrations of the time were Harper's reporting on the war. Besides renderings by Homer and Nast, the magazine also published illustrations by Theodore R. Davis, Henry Mosler, and the brothers Alfred and William Waud.

In 1863, George William Curtis, one of the founders of the Republican Party, became the political editor of the magazine, and remained in that capacity until his death in 1892. His editorials advocated civil service reform, low tariffs, and adherence to the gold standard.[7]

"President maker"

After the war, Harper's Weekly more openly supported the Republican Party in its editorial positions, and contributed to the election of Ulysses S. Grant in 1868 and 1872. It supported the Radical Republican position on Reconstruction. In the 1870s, the cartoonist Thomas Nast began an aggressive campaign in the journal against the corrupt New York political leader William "Boss" Tweed. Nast turned down a $500,000 bribe to end his attack.[8] Tweed was arrested in 1873 and convicted of fraud.

Nast and Harper's also played an important part in securing Rutherford B. Hayes' 1876 presidential election. Later on Hayes remarked that Nast was "the most powerful, single-handed aid [he] had".[9] After the election, Nast's role in the magazine diminished considerably. Since the late 1860s, Nast and George W. Curtis had frequently differed on political matters and particularly on the role of cartoons in political discourse.[10] Curtis believed that mockery by caricature should be reserved for Democrats, and did not approve of Nast's cartoons assailing Republicans such as Carl Schurz and Charles Sumner, who opposed policies of the Grant administration. Harper's publisher Fletcher Harper strongly supported Nast in his disputes with Curtis. In 1877, Harper died, and his nephews, Joseph W. Harper Jr. and John Henry Harper, assumed control of the magazine. They were more sympathetic to Curtis' arguments for rejecting cartoons that contradicted his editorial positions.[11]

In 1884, however, Curtis and Nast agreed that they could not support the Republican candidate James G. Blaine, whose association with corruption was anathema to them.[12] Instead they supported the Democratic candidate, Grover Cleveland. Nast's cartoons helped Cleveland become the first Democrat to be elected President since 1856. In the words of the artist's grandson, Thomas Nast St Hill, "it was generally conceded that Nast's support won Cleveland the small margin by which he was elected. In this his last national political campaign, Nast had, in fact, 'made a president.'"[13]

Nast's final contribution to Harper's Weekly was his Christmas illustration in December 1886. Journalist Henry Watterson said that "in quitting Harper's Weekly, Nast lost his forum: in losing him, Harper's Weekly lost its political importance."[14] Nast's biographer Fiona Deans Halloran says "the former is true to a certain extent, the latter unlikely. Readers may have missed Nast's cartoons, but Harper's Weekly remained influential."[15]

Early 1900s

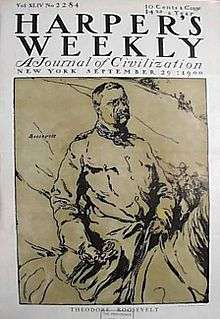

After 1900, Harper's Weekly devoted more print to political and social issues, and featured articles by some of the more prominent political figures of the time, such as Theodore Roosevelt. Harper's editor George Harvey was an early supporter of Woodrow Wilson's candidacy, proposing him for the Presidency at a Lotos Club dinner in 1906.[16] After that dinner, Harvey would make sure that he "emblazoned each issue of Harper's Weekly with the words 'For President—Woodrow Wilson'".[17]

Harper's Weekly published its final issue on May 13, 1916.[18] It was absorbed by The Independent, which in turn merged with The Outlook in 1928.

1970s

In the mid-1970s Harper's Magazine used the Harper's Weekly title for a spinoff publication, again published in New York. Published biweekly for most of its run, the revived Harper's Weekly depended on contributions from readers for much of its content.

Publications

On January 14, 1893, Harper's Weekly became the first American magazine to publish a Sherlock Holmes story—"The Adventure of the Cardboard Box".[19]

See also

Notes

- 1 2 Palmquist & Kailborn 2002, p. 279.

- ↑ Halloran 2012, p. 289.

- ↑ Halloran 2012, p. 214.

- ↑ http://onlinebooks.library.upenn.edu/webbin/serial?id=harpersweekly

- ↑ Heidler et al 2002, p. 931.

- ↑ Goodyear, "Photography changes ..."

- ↑ Halloran 2012, p. 254.

- ↑ Paine 1904, pp. 181–182.

- ↑ Paine 1904, p. 349.

- ↑ Halloran 2012, p. 228.

- ↑ Halloran 2012, p. 230.

- ↑ Halloran 2012, p. 255.

- ↑ Nast & St. Hill 1974, p. 33.

- ↑ Paine 1904, p. 528.

- ↑ Halloran 2012, p. 270.

- ↑ Link 1970, p. 4.

- ↑ Throntveit 2008, p. 30.

- ↑ Mott 1938, p. 469.

- ↑ Panek 1990, p. 53.

References

- DeBrava, Valerie (2001). "The Offending Hand of War in Harper's Weekly," American Periodicals, vol. 11, pp. 49-64. In JSTOR

- Goodyear III, Frank H. "Photography changes the way we record and respond to social issues". Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on May 1, 2013. Retrieved 26 August 2013.

- Halloran, Fiona Deans (2012). Thomas Nast: The Father of Modern Political Cartoons. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-80783-587-6.

- Heidler, David Stephen; Heidler, Jeanne T.; Coles, David J. (2002). Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-39304-758-X.

- Link, Arthur S. (February 1970). "Woodrow Wilson: The American as Southerner". The Journal of Southern History. 36 (1): 3–17. doi:10.2307/2206599.

- Mott, Frank Luther (1938). A History of American Magazines, 1850–1865. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-39551-0.

- Nast, Thomas; St. Hill, Thomas N. (1974). Thomas Nast: Cartoons and Illustrations. New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-23067-8.

- Paine, Albert Bigelow (1904). Th. Nast, His Period and His Pictures. MacMillan – via Internet Archive.

- Palmquist, Peter; Kailborn, Thomas (2002). Pioneer Photographers of the Far West: A Biographical Dictionary, 1840–1865. Stanford University Press.

- Panek, LeRoy L. (1990). Probable Cause: Crime Fiction in America. Popular Press. ISBN 978-0-87972-486-3.

- Prettyman, Gib (2001). "Harper's Weekly and the Spectacle of Industrialization," American Periodicals, vol. 11, pp. 24-28. In JSTOR

- Throntveit, Trygve (2008). "'Common Counsel': Woodrow Wilson's Pragmatic Progressivism, 1885–1913". In John Milton Cooper Jr. Reconsidering Woodrow Wilson. Woodrow Wilson Center Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-9074-1.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Harper's Weekly. |

- Online Books Page. Harper's Weekly digitized issues, various dates

- Virginia Civil War Archive – online images including those illustrations in Harper's Weekly during 1861–1865 that relate specifically to the Commonwealth of Virginia and its part in the Civil War.

- Access for Issues 1861–1865 via sonofthesouth.net

- Hathi Trust. Harper's Weekly