Harlon Block

| Harlon Block | |

|---|---|

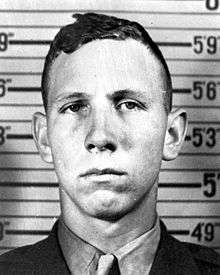

Block in 1943 | |

| Birth name | Harlon Henry Block |

| Born |

November 6, 1924 Yorktown, Texas |

| Died |

March 1, 1945 (aged 20) Iwo Jima, Japan |

| Buried | Harlingen, Texas |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/branch |

|

| Years of service | 1943 – 1945 |

| Rank | Corporal |

| Unit | E Company, 2nd Battalion, 28th Marines, 5th Marine Division |

| Battles/wars |

|

| Awards |

Purple Heart Medal Combat Action Ribbon |

Harlon Henry Block (November 6, 1924 – March 1, 1945) was a United States Marine Corps corporal who was killed in action during the Battle of Iwo Jima in World War II.

Born in Yorktown, Texas, Block joined the Marine Corps with seven high school classmates in February 1943, and subsequently participated in combat on Bougainville and Iwo Jima. He is best known for being one of the six flag-raisers who helped raise the second U.S. flag atop Mount Suribachi on February 23, 1945, as shown in the iconic photograph Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima.

The Marine Corps War Memorial located in Arlington, Virginia, which was modeled after the flag-raising photograph, depicts bronze statues of each of the six Marine flag-raisers.

Early life

Block was born in Yorktown, Texas, the third of six children to Edward Frederick Block and Ada Belle Brantley, a Seventh day-Adventist family.[1][2] The Block children were: Edward, Jr., Maurine, Harlon, Larry, Corky, and Melford.[3] Edward Frederick Block was a World War I veteran and supported his family by working as a dairy farmer.[4] In hopes of improving the family, the Block family relocated to Weslaco, Texas, a city located in the Rio Grande Valley. His father became a dairy farmer, and the children attended a Seventh-day Adventist private school. Harlon Block was expelled in his freshman year when he refused to tell the principal which student had vandalized the school. Block then transferred to Weslaco High School and was remembered as an outgoing student with many friends. A natural athlete, Block led the Weslaco Panther Football Team to the Conference Championship. He was honored as "All South Texas End". Block and seven of his high school friends decided on joining the Marine Corps before they graduated and the school held a special early graduation ceremony for them in January 1943.[5]

U.S. Marine Corps

World War II

Block and seven of his high school football teammates enlisted together in the Marine Corps through the Selective Service System at San Antonio on February 18, 1943 and were sent to recruit training at the Marine Corps Recruit Depot in San Diego. On April 14, Block began parachute training at the Marine Parachute Training School in San Diego, and on May 22, he qualified as a Paramarine and was promoted to private first class. He was sent to the Pacific Theater. He arrived at New Caledonia on November 15, where he served as a member of Headquarters and Service Company, 1st Marine Parachute Regiment, I Marine Amphibious Corps. On December 21, he landed on Bougainville. On December 22, 1st Parachute Battalion, Weapons Company and a Headquarters and Service platoon attached to the 2nd Marine Raider Regiment, relieved the 1st Battalion, 3rd Marines in the vicinity of Eagle Creek on Bougainville. Block returned to San Diego with his unit on February 14. On February 29, the parachutists disbanded and Block joined the Second Platoon, E Company, 2nd Battalion, 28th Marine Regiment, 5th Marine Division at Camp Pendleton, California on March 1. He was promoted to corporal on October 27, 1944.

Flag raising(s) on Mount Suribachi

On February 19, 1945, Block landed with the Second Battalion, 28th Marines who were nearest to Mount Suribachi at the southern end of Iwo Jima which was the battalion's objective, and fought in the battle for the capture of the island. On February 23, a 40-man patrol from mostly Third Platoon, Easy Company, was sent up Mount Suribachi to seize and occupy the crest and raise an American flag to signal that the mountaintop was captured. The patrol led by First Lieutenant Harold Schrier who carried the battalion's flag, left 8 AM and soon made it to the top of Mount Suribachi. The flag was raised by Lt. Schrier, Platoon Sergeant Ernest Thomas, and Sergeant Henry Hansen.[6] After a brief firefight with Japanese soldiers who were hiding in caves after the flag was raised, the summit was secured.

It was determined that the flag was too small to be seen on the north side of Mount Suribachi (where most of the Japanese were located and heavier fighting would occur), so another and larger flag was called for. At around noon or so, Marine Sgt. Michael Strank was ordered to take three of his squad members in Second Platoon up to the top of Suribachi with supplies and raise a replacement flag. He then chose Cpl. Block (assistant squad leader), Pfc. Ira Hayes, and Pfc. Franklin Sousley to go with him up the mountain. Pfc. Rene Gagnon, the Easy Company runner (messenger), was ordered to take the flag up and return with the first flag.

Once on top, Strank told Hayes and Sousley to find a pipe to be used for a flagpole to tie the flag on. The flag was attached to a Japanese steel pipe they found, and as the four Marines were about to raise the flagstaff, Strank called for help from Gagnon and Pfc. Harold Schultz (Navy corpsman John Bradley was incorrectly identified as a flag-raiser until June 23, 2016)[7] The six Marines then raised the replacement flag together as the first flag and flagstaff was lowered under Lt. Schrier's command. The second raising was immortalized forever by the black and white photo of the flag raising by Joe Rosenthal of the Associated Press. This flag-raising was also filmed in color by Sergeant Bill Genaust who was killed in action on March 4. Strank was killed in action on March 1, and Sousley on March 21, five days before the battle ended on March 26.

Death

According to the book Flags of Our Fathers by James Bradley (son of Navy corpsman John Bradley), Block then assumed command of Strank's squad in Second Platoon after Strank was killed on March 1, and later the same day Block was mortally wounded by an enemy mortar round explosion while leading the squad during an attack toward Nishi Ridge. Block's last words were, "They killed me!".[8] However, Ralph Griffiths, a member of the same platoon as Block, claimed that Strank and Block were killed instantly by the same shell which wounded him on March 1.[9][10][11] Block was originally buried in the 5th Marine Division Cemetery on Iwo Jima in 1945. A service was held there on March 26 which included Hayes and other members of Easy Company. In January 1949, Block's remains was re-interred in Weslaco, Texas. In 1995, his body was moved to a burial place at the Marine Military Academy near its Iwo Jima monument in Harlingen, Texas.[1][12]

Flag raising controversy

A controversy arose as to the identity of the person shown at the right end and bottom of the flagstaff in the famous photograph of the second flag-raising on Mount Suribachi. When Block's mother first viewed Rosenthal's iconic photograph of the second flag-raising in the Weslaco newspaper on February 25, 1945, just two days after the photo was taken, she immediately exclaimed, "That's Harlon", pointing to the flag-raiser on the far right. She never wavered in her belief that it was Harlon in the photo, insisting, "I know my boy."

On March 27, 1945, the 28th Marines departed Iwo Jima for Hawaii. On March 30, President Franklin Roosevelt (died on April 12, 1945) ordered the Marine Corps to send the flag-raisers in Rosenthal's photograph to Washington, D.C. where it was determined that Hansen was in the photograph. On April 7, Rene Gagnon (Easy Company's runner (messenger)), mistakenly identified the person in the photograph as Sergeant Hank Hansen of Boston (Hansen was a member of Third Platoon of Company E, who had participated in the first flag-raising on Mount Suribachi earlier that morning).[13] On April 8, the Marine Corps released publicly the names of the six flag-raisers in the photograph which were identified by Gagnon (he also incorrectly identified Bradley in the photograph).[7] When Navy corpsman John Bradley (Third Platoon corpsman, Easy Company, who was involved with the first flag-raising on Suribachi) arrived in Washington, D.C. a few days later, Bradley (he incorrectly identified himself in the photograph)[7] concurred with Gagnon that Hansen was in the photograph. However, on April 19, when Ira Hayes (Second Platoon) arrived in Washington, D.C., he told the lieutenant colonel interviewing him (also interviewed Gagnon and Bradley) about who the flag-raisers were, that an "error" was made, Block (Second Platoon) and not Hansen was at the base of the flagstaff in the photo. Hayes (who incorrectly identified Bradley in the photograph)[7] was then told the six names (Hansen...) were already released and since Block and Hansen were both deceased, to not say a word about it again[14](the lt. colonel later claimed Hayes never mentioned Block's name to him).

In 1946, after Hayes was honorably discharged from the Marine Corps (December 1945), he visited Mr. Block at his home and told him Harlon was in the photograph. Mrs. Block then persuaded Mr. Block to write their congressman about the matter which he did in September, and the Marine Corps replied that an investigation would be held by them into the identities of the second flag-raisers in the Rosenthal photograph. During the following investigation, Hayes's written statements and letter to Mrs. Block in September 1945, were instrumental in proving Harlon Block was in the famous photograph and Hansen was not (Hayes, and Hansen who wore parachutist boots on Suribachi... were former Paramarines). Gagnon and Bradley who said it was Hansen, agreed that "it could be Block" after learning why Hayes said it was Block. The investigation which began in December and concluded in January 1947, found that it was indeed Block and not Hansen in the picture, and that no blame was to be placed on anyone in this matter.

Marine Corps War Memorial

The Marine Corps War Memorial (also known as the Iwo Jima Memorial) in Arlington, Virginia which was inspired by Rosenthal's photograph of the second flag raising on Mount Suribachi was dedicated on November 10, 1954.[15] Block is depicted as the first bronze statue at the bottom of the flagstaff with the 32 foot (9.8 m) bronze statues of the other five flag-raisers on the monument (as of June 23, 2016, Franklin Sousley is depicted as the third bronze statue from the bottom of the flagstaff and Harold Schultz is depicted as the fifth statue from the bottom of the flagstaff).[7]

President Dwight D. Eisenhower sat upfront with Vice President Richard Nixon, Deputy Secretary of Defense Robert Anderson, and General Lemuel C. Shepherd, the 20th Commandant of the Marine Corps during the dedication ceremony. Two of the three surviving flag-raisers depicted on the monument, Ira Hayes and Rene Gagnon, were seated together with John Bradley (he was incorrectly identified as a surviving flag-raiser)[7] in the front rows of seats along with relatives of those who were killed in action on the island.[16] Speeches were given by Richard Nixon, Robert Anderson who dedicated the memorial, and General Shepherd who presented the memorial to the American people.[17] Inscribed on the memorial are the following words:

- In Honor And Memory Of The Men of The United States Marine Corps Who Have Given Their Lives To Their Country Since 10 November 1775

Military awards

Block's military decorations and awards include:

| Navy Presidential Unit Citation | ||

| American Campaign Medal | Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal with two 3⁄16" bronze stars | World War II Victory Medal |

Parachutist Badge Parachutist Badge |

Rifle Sharpshooter Badge Rifle Sharpshooter Badge |

Note: The Marine Corps Good Conduct Medal in World War II required 4 years of serice.

Portrayal in film

Harlon Block is featured in the 2006 Steven Spielberg and Clint Eastwood film Flags of Our Fathers, directed by Clint Eastwood and produced by Eastwood, Spielberg and Robert Lorenz. In the movie, Block is portrayed by American actor Benjamin Walker. His parents are portrayed by Christopher Curry and Judith Ivey. The film is based on the 2000 book of the same title.

Public honors

- Marine Corps War Memorial

- Harlon Block exhibit, Weslaco Museum, Weslaco, Texas

- Harlon Block Memorial (Texas National Guard Armory), Weslaco, Texas

- Harlon Block Sports Complex (Park), Weslaco, Texas

See also

- Flags of Our Fathers

- Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima

- Shadow of Suribachi: Raising The Flags on Iwo Jima

- Meliton Kantaria - Soviet flag raiser over the Reichstag in Berlin, 1945.

- Mikhail Yegorov - Soviet flag raiser over the Reichstag in Berlin, 1945.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Harlon Block. |

References

- 1 2 "Block, Harlon Henry". The Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 28 October 2015.

- ↑ "Famed Iwo Jima flag raisers gone but not forgotten". Marines.mil. Retrieved 2012-05-17.

- ↑ Bradley, p. 31.

- ↑ Flags of Our Fathers by James Bradley, p. 29.

- ↑ Hendricks, Mark (7/26/2001), Iwo Jima: In Memory Of A Friend, 7/26/2001 Retrieved January 10, 2015

- ↑ Rural Florida Living. Thomas was interviewed by CBS radio broadcaster Dan Pryor on February 25, 1945, aboard the USS Eldorado (AGC-11): "Three of us actually raised the flag".

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 USMC Statement on Marine Corps Flag Raisers, Office of U.S. Marine Corps Communication, 23 June 2016

- ↑ Bradley, James (May 2000). Flags of Our Fathers. New York: Bantam Books. pp. 232–233. ISBN 0-553589-34-2.

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ "Harlon Block". Find a Grave. Retrieved September 22, 2010.

- ↑ Rural Florida Living. CBS Radio interview by Dan Pryor with flag raiser Ernest "Boots" Thomas on February 25, 1945 aboard the USS Eldorado (AGC-11): "Three of us actually raised the flag"

- ↑ Bradley, James. Flags of Our Fathers. p. 417.

- ↑ The Marine Corps War Memorial Marine Barracks Washington, D.C.

- ↑ "Memorial honoring Marines dedicated". Reading Eagle. Pennsylvania. Associated Press. November 10, 1954. p. 1.

- ↑ "Marine monument seen as symbol of hopes, dreams". Spokane Daily Chronicle. Washington. Associated Press. November 10, 1954. p. 2.

- ↑ Combat Action Ribbon (1969): Retroactive from December 7, 1941: Public Law 106-65, October 5, 1999, 113 STAT 508, Sec. 564