Harlequin Cock Robin and Jenny Wren

Harlequin Cock Robin and Jenny Wren; or, Fortunatus and the Water of Life, the Three Bears, the Three Gifts, the Three Wishes, and the Little Man who Woo'd the Little Maid[1] was a pantomime written by W. S. Gilbert. As with many pantomimes of the Victorian era, the piece consisted of a story involving evil spirits, young lovers and "transformation" scenes, followed by a harlequinade.

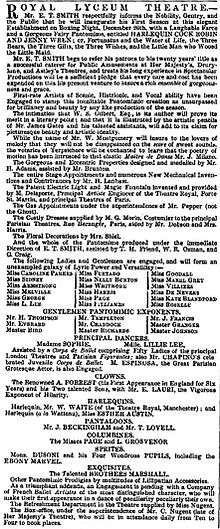

The piece premiered at the Lyceum Theatre, London on 26 December 1867. It was the only pantomime written by Gilbert alone, although before and afterwards he collaborated with other authors on pantomimes for the London stage. It was written early in his career, when he was not yet an established playwright, and the script was regarded as of less importance than the spectacle. The first night was under-rehearsed, and the spectacular effects and scenery failed to work properly. Later performances were satisfactory in that respect, and the piece received some good reviews.

Background

Gilbert had always been fascinated by pantomime.[2] In 1865, he had written Pantomimic Presentiments, one of his Bab Ballads, satirising pantomime and complaining that "I'm beginning to get weary of dramatic desert dreary,/ And I ask myself a query, when will novelties begin?"[3] Gilbert had collaborated on an earlier pantomime, Hush-a-Bye, Baby, on the Tree Top, in 1866.[4] Immediately following his production of Harlequin Cock Robin, Gilbert published an article called "Getting Up a Pantomime".[5] His 1875 opera with Arthur Sullivan, Trial by Jury, included a pantomime-style transformation scene (especially prominent in the 1884 version), and he collaborated on The Forty Thieves, a pantomime written as a charity fund-raiser in 1878, in which he played Harlequin.[6] His last full-length play, The Fairy's Dilemma (1904), drew heavily on (and satirised) pantomimic conventions. But Harlequin Cock Robin was Gilbert's only solo essay in the genre of traditional pantomime.[7]

In the West End, during the mid-19th century, pantomimes traditionally opened at the major theatres on 26 December, known in England as Boxing Day, intended to play for only a few weeks into the new year. Gilbert's pantomime opened on the same night as rival shows at the Drury Lane Theatre, Covent Garden, Sadler's Wells, and eight other London theatres. Less well-established pantomime venues opened on Christmas Eve to give themselves an edge over the competition; seven such shows opened on 24 December 1867.[8] The writers of the rival shows included established authors such as Mark Lemon, Gilbert à Beckett, C. H. Hazlewood and E. L. Blanchard.[8] Gilbert's piece ran until the end of February 1868, being given about 83 performances. So, notwithstanding Gilbert's statement about it in 1868, it gained average success for a Christmas pantomime.[9]

At this early stage of his career as a playwright, Gilbert had only two substantial successes behind him – his burlesques, Dulcamara! or, The Little Duck and the Great Quack and La Vivandière; or, True to the Corps!. Professionally, he was not yet in a position to control the casting or staging of his works. In 1884, he wrote a humorous article for the annual almanac published by The Era recalling the chaotic circumstances of the production of his pantomime.

The piece was written in four days and produced in about three weeks … [A]ll the laughs in the piece were the stage manager's. I was rude to him at the time, but I apologise to him now. The rehearsals, of course, were a wild scramble. Everybody was going to introduce a song or a dance (unknown to me), and these songs and dances were rehearsed surreptitiously in corners. … At about four o'clock on Boxing-day [the day of the opening] instalments of the scenery began to arrive—three pairs of wings, then half a flat, then a couple of sky borders and so on. When the curtain rose on the piece about three complete scenes had arrived. ... [A] "Fish Ballet" entered (very shiny and scaly but otherwise not like any fish I have ever met) and danced a long ballet, which they themselves thoughtfully encored. Then came the clever and hardworking lady with another song (from last year's pantomime). Then a can-can by the Finette troupe. Then a party of acrobats. Then the spotted monarch's mystic dance. Altogether a chain of events calculated to arrest the attention of a wayfarer through that wood and set him pondering.

Gilbert's article also mentions that he was paid £60 for Harlequin Cock Robin. This was twice what he had been paid for the libretto of Dulcamara in 1866, but was still a modest sum for the time.[10] The Gilbert scholar Jane Stedman notes that this production had "the questionable honour of introducing the cancan to the English stage."[11] Men flocked to see what one paper called "the most gross and filthy exhibition that has ever disgraced our degenerate stage."[12]

Gilbert's early pantomimes, burlesques and farces, full of awful puns and broad humour, show signs of the satire that would later be a defining part of his work.[13] These works gave way, after 1869, to plays containing original plots and fewer puns.[14] These included his "fairy comedies", such as The Palace of Truth (1870) and Pygmalion and Galatea (1871), and his German Reed Entertainments, which led to the famous Gilbert and Sullivan operas.[15]

Roles and cast

- Evil Spirits

- The Demon Miasma (an awfully bad lot though a Fiend of common scents) – Henry Thompson

- Ague and Malaria (his offensive offspring) – Misses Villiers and Kate Blandford

- Satana (a supernatural preternatural and altogether utterly unnatural Mephistophelian personage – in league with Miasma) – Miss Goodall.[16]

- Demonio (not the Bel of that name but a Metallic Monster, the dumb familiar of Miasma who hasn't a word to say for himself, so is by no means vulgar) – M. Espinosa

- Good Spirits

- The Spirit of Fresh Air (a beneficent Fairy, the Guardian Spirit of Dicky-Birds in general and Cock-Robin in particular, Jenny Wren's lively friend, and Miasma's deadly foe) – Minnie Sydney

- Health and Happiness (her attendant Spirits, Godmothers of Cock-Robin and Jenny Wren) – Nellie Burton and Lizzie Grosvenor

- Fairies Oak, Willow and Fir (her three Fairy Subordinates who are rooted to one spot but are never in want of change as they always have a little Sylva about them) – Misses Mabel Gray, Whitmore, and Page

- Fairy Cook, Fairy Butler and Fairy Fortune (Low menials who provide for Cock Robin's Hy-meneal, with her wheel but without her woe) – Misses Flowers, De Nevers, and Roselle

- Fairy of the Fountain (The Spirit of the Water of Life, not to be confounded with the Spirit of Eau de Vie) – Miss O. Armstrong

- First Fairy. – Miss Laidlaw

- Wicked Animals

- Cuckoo, Raven and Sparrow (three conspicuous Conspirators, base to the back-bone, rejected lovers of Jenny Wren) – Masters Bird, Beaker, and Mr. J. Francis

- Great Bear, Middle-sized Bear and Little Bear (afterwards changed into three baser Bar-bear-ians and more rejected than ever by Jenny) – Mr. Templeton, Mr. Everard, and Master Grainger

- Virtuous Animals

- Cock-Robin (the Bird who has been the burd-en of many a rhyme, the Cock that no one can be Robin of his fame whose he-red-itary red breast can be recognised by hen-nybody) – Caroline Parkes

- Jenny Wren (the little Wren who has ren-dered up her liberty to the Dicky-Bird of her heart and nearly breaks it when he hops the twig) – Teresa Furtado

- Descriptive Description of Dicky-Birds: Messrs. Twit, Twitter and Twutter, Flit, Flitter, Fly and Flutter, Hop, Pop, Crop, Pick, Peck, Tweet, Sweet, Dick, Chick, Beak, Tweak, Chip, Chow, Bill and Coo, Chatter and Chirrup, &c.

- Mortals

- Little Man – Caroline Parkes

- Little Maid – Teresa Furtado

- Gaffer Gray (Little Maid's Pa) – Mr. Marshall

- Laundry-Women – Mesdames Suds, Soda, and Starch

- Mammoth Monsters

- The Giant Herlotrobosanguinardodiotso – John Craddock

- The Giant's Footman Lengthylankyshankylongo – Mr. Tallboy

- The Giant Wittleemgobbleem – Mr. Wolfem

- The Giant Clubemdrubem – Mr. Gogmagog

- The Giant Feedy Greedy – Mr. Hungryman

- The Giant Savagusravenous – Mr. Chopemup

- The Giant Gorgeumsplorgum – Mr. Longswallow

Other Personalities by Legions of Useful Utilities and Superior Supernumeraries. Members of the Vokes family danced in the piece.[17]

Note: the parenthetical descriptions of the characters are Gilbert's own.

Synopsis

The magazine The Orchestra printed the following description of the plot:

The story opens in the Demon Miasma's Dismal Swamp. Miasma, indignant at the ascendancy that his old foe, Fresh Air, is gaining over him, consults with Satana as to the best means of revenging himself on the fairy. He cannot enter her pure realms himself, so he is fain to intrust the accomplishment of his designs upon her to three wicked birds – the Sparrow, the Cuckoo, and the Raven. They explain that they cannot kill her as Miasma suggests, because Fresh Air is absolutely necessary to their existence, but they offer to kill her favourite child, Cock Robin, who is that day to be united to Jenny Wren, of whom the Sparrow, the Cuckoo, and the Raven are rejected admirers. Health and Happiness overhear this conspiracy, and interpose to plead for Cock Robin's life, but Miasma is inexorable, and the three birds, attended by Satana and her dumb-familiar Demonio, betake themselves to The Abode of the Spirit of Fresh Air, who is then in the act of receiving the various feathered guests, whom she has invited to the grand wedding of Cock Robin and Jenny Wren. Just as the happy pair are on the point of being united, the Cuckoo attempts to kiss Jenny Wren, and the Sparrow, pretending to shoot Cuckoo as a punishment for his madness, kills Cock Robin. A court-martial is held, and, on the evidence of "the fly who saw him die", and "the fish who caught his blood", the Sparrow and his companions are found guilty. As summary justice is about to be wreaked on them, their friend Satana changes them into three bears.

The next scene takes place in the forest, where Cock Robin is to be buried. Fairy Fresh Air transforms the dead body of Robin into a live little man. We now come to The Home of the Three Bears. Jenny seeks shelter in their new abode from the storm, and, finding the house unoccupied, takes the liberty of tasting the porridge prepared for the breakfast of the bears. After sitting in all their chairs, and trying all their beds, she finally goes a nid nid nodding on the bed of The Little Bear. The three bears return, and, finding their porridge eaten and their beds tumbled, seize on Little Maid and turn her into a pie, but Little Man arrives, defeats the three bears and Demonio. A fairy at that moment appears, and gives them a magic ring, which entitles the holder to three wishes. The Little Man and Little Maid transfer the responsibility of wishing to Gaffer and Gammer Guy, Little Maid's father and mother. Through the agency of Demonio, the old lady desires that a black pudding shall come down the chimney ready dressed. Her wish is realised, and the Old Gentleman wishes as a punishment it may stick to her nose. This it does, and the old lady wishes the pudding off again.

The good Fairy, Fortune, appears, and gives Little Man a magic purse, a magic cap, and a magic sword, conferring unlimited wealth, universal locomotion, and absolute invincibility. Little Man gives Little Maid the magic purse, and leaves her to find the waters of unceasing life. He at last reaches the fountain in safety, notwithstanding many vicissitudes on the road, in one of which he encounters the great Ogre Herlotrobosanguinardodiotso, and in compassing whose destruction relieves the lilliputian inhabitants of Toy Island of their terror-instilling tyrant. But Satana has cited Demonio to drug the waters of the fountain, and when Little Man imbibes what he imagines the waters of life he is dismally disappointed, and becomes stupefied. The three bears have mustered their army to pepper Little Maid's castle, and upon which, headed by Satana, they make a successful assault, and carry her off into The Depths of the Dingle Dell. Little Man, however, follows, and is about rescuing his lady love when the noxious Miasma appears and overwhelms them with his unhealthy fumes. Fresh Air penetrates the formidable forest, and asserts her supremacy by reviving the two lovers, and transforms them into Harlequin and Columbine and the transformation takes place.[18]

Critical reception

The papers remarked on the chaos of the first night. The Times wrote, "Few managers would have attempted to get up such a pantomime within the very short time Mr. E. T. Smith has had possession of the Lyceum. The want of sufficient preparation was manifest in more than one instance during the first night's performance; but had everything gone off perfectly smooth, such a result would, perhaps, have surprised persons much more than did the drawbacks for which Mr. Smith felt it necessary to ask the forbearance of the audience."[19] The review comments on the elaborate requirements of the piece: "This is a pantomime with not merely a single transformation, but three changes leading up to the comic business; and when the latter commences there are four clowns, two harlequins, a harlequin à la Watteau – played by a lady – two columbines, two pantaloons, five sprites, and two “exquisites,” besides scores of supernumerary comic pantomimists, in the shape of policemen, costermongers, butchers’ boys, &c."[19]

Once the piece had settled in, the reviews were favourable. The Era wrote, "The Pantomime is now in proper working order, the audience increase at each representation, and there is every prospect of a triumphant success."[20]

Notes

- ↑ W. R. Osman had written a pantomime called "Harlequin Cock Robin and the Children in the Wood" in 1866. See Nicoll, Allardyce. A History of English Drama, 1660–1900, Volume 6, p. 206, Cambridge University Press, 2009 ISBN 0-521-10933-7

- ↑ Crowther, Andrew. "Clown and Harlequin", W. S. Gilbert Society Journal, vol. 3, issue 23, Summer 2008, pp. 710–21

- ↑ Pantomimic Presentiments, Bab Ballads, originally published in Fun magazine on 7 October 1865, reprinted at The Gilbert and Sullivan Archive, accessed 31 December 2010

- ↑ Stedman, pp. 34–35

- ↑ Gilbert, W. S. "Getting Up a Pantomime", London Society, January 1868, pp. 50–51; Crowther, pp. 716–17

- ↑ Hollingshead, John. Good Old Gaiety: An Historiette & Remembrance, pp. 39–41 (1903) London: Gaity Theatre Co

- ↑ Stedman, passim

- 1 2 "The Christmas Burlesques and Pantomimes", The Era Almanack, 1868, p. 60

- ↑ Moss, Simon. "Harlequin Cock-Robin and Jenny Wren", c20th.com, W. S. Gilbert archive, accessed 31 December 2010

- ↑ W. S. Gilbert, "My Pantomime" , The Era Almanack, 1884, pp. 77–79

- ↑ Stedman, p. 53

- ↑ Stedman, p. 54

- ↑ See The Cambridge History of English and American Literature, Volume XIII, Chapter VIII, Section 15 (1907–21) and Crowther, Andrew, The Life of W. S. Gilbert.

- ↑ Crowther, Andrew. The Life of W. S. Gilbert

- ↑ Article by Andrew Crowther.

- ↑ Evidently not Bella Goodall, who was appearing in a rival Christmas show at the time

- ↑ "The Vokes Family". Its-behind-you.com, accessed 31 December 2010

- ↑ "The Pantomimes", The Orchestra, 28 December 1867, p. 213

- 1 2 "Lyceum Theatre", The Times, 27 December 1867

- ↑ "Progress of the Pantomimes", The Era, 12 January 1868, p. 11

References

- Stedman, Jane W. (1996). W. S. Gilbert, A Classic Victorian & His Theatre. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-816174-3.

External links

Libretto of Harlequin Cock Robin and Jenny Wren