Har Gobind Khorana

| Har Gobind Khorana | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

9 January 1922 Raipur,[1] British India (now Raipur, Pakistan) |

| Died |

9 November 2011 (aged 89) Concord, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Residence |

British India United States United Kingdom |

| Citizenship | United States, British India |

| Fields | Molecular biology |

| Institutions |

|

| Alma mater | |

| Known for | First to demonstrate the role of nucleotides in protein synthesis |

| Notable awards | |

|

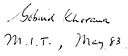

Signature  | |

Har Gobind Khorana (9 January 1922 – 9 November 2011),[4][5] was an Indian-American biochemist who shared the 1968 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine with Marshall W. Nirenberg and Robert W. Holley for research that showed how the order of nucleotides in nucleic acids, which carry the genetic code of the cell, control the cell’s synthesis of proteins. Khorana and Nirenberg were also awarded the Louisa Gross Horwitz Prize from Columbia University in the same year.[6][7]

Khorana was born in Raipur, British India (today Tehsil Kabirwala, Punjab, Pakistan). He served on the faculty of the University of British Columbia from 1952-1960, where he initiated his Nobel Prize winning work. He became a naturalized citizen of the United States in 1966,[8] and subsequently received the National Medal of Science. He co-directed the Institute for Enzyme Research,[9] became a professor of biochemistry in 1962 and was named Conrad A. Elvehjem Professor of Life Sciences at University of Wisconsin–Madison.[10] He served as MIT's Alfred P. Sloan Professor of Biology and Chemistry, Emeritus[11] and was a member of the Board of Scientific Governors at The Scripps Research Institute.

Research work

Ribonucleic acid pro (RNA) with three repeating units (UCUCUCU → UCU CUC UCU) produced two alternating amino acids. This, combined with the Nirenberg and Leder experiment, showed that UCU codes for Serine and CUC codes for Leucine. RNAs with three repeating units (UACUACUA → UAC UAC UAC, or ACU ACU ACU, or CUA CUA CUA) produced three different strings of amino acids. RNAs with four repeating units including UAG, UAA, or UGA, produced only dipeptides and tripeptides thus revealing that UAG, UAA and UGA are stop codons.[12]

With this, Khorana and his team had established that the mother of all codes, the biological language common to all living organisms, is spelled out in three-letter words: each set of three nucleotides codes for a specific amino acid. Their Nobel lecture was delivered on 12 December 1968.[12] Khorana was the first scientist to chemically synthesize oligonucleotides.[13]

Subsequent research

He extended the above to long DNA polymers using non-aqueous chemistry and assembled these into the first synthetic gene, using polymerase and ligase enzymes that link pieces of DNA together,[13] as well as methods that anticipated the invention of PCR.[14] These custom-designed pieces of artificial genes are widely used in biology labs for sequencing, cloning and engineering new plants and animals, and are integral to the expanding use of DNA analysis to understand gene-based human disease as well as human evolution. Khorana's invention(s) have become automated and commercialized so that anyone now can order a synthetic oligonucleotide or a gene from any of a number of companies. One merely needs to send the genetic sequence to one of the companies to receive an oligonucleotide with the desired sequence.

Since the middle of the 1970s, his lab has studied the biochemistry of bacteriorhodopsin, a membrane protein that converts light energy into chemical energy by creating a proton gradient.[15] Later, his lab went on to study the structurally related visual pigment known as rhodopsin.[16]

Awards and honours

Khorana was elected as Foreign Member of the Royal Society (ForMemRS) in 1978.[3] The University of Wisconsin-Madison, the Government of India (DBT Department of Biotechnology), and the Indo-US Science and Technology Forum jointly created the Khorana Program in 2007. The mission of the Khorana Program is to build a seamless community of scientists, industrialists, and social entrepreneurs in the United States and India.

The program is focused on three objectives: Providing graduate and undergraduate students with a transformative research experience, engaging partners in rural development and food, security, and facilitating public-private partnerships between the U.S. and India. In 2009, Khorana was hosted by the Khorana Program and honored at the 33rd Steenbock Symposium in Madison, Wisconsin.[9]

Death

Khorana died of natural causes on 9 November 2011 in Concord, Massachusetts, aged 89.[17] A widower since 2001, he was survived by his children Julia and Davel.[18]

References

- ↑ GELLENE, DENISE (14 November 2011). "H. Gobind Khorana, 89, Nobel-Winning Scientist, Dies". The New York Times. Retrieved 4 August 2016.

- ↑ http://www.gcu.edu.pk/About.htm

- 1 2 "Fellowship of the Royal Society 1660-2015". London: Royal Society. Archived from the original on 15 July 2015.

- ↑ Caruthers, M.; Wells, R. (2011). "Har Gobind Khorana (1922-2011)". Science. 334 (6062): 1511. PMID 22174242. doi:10.1126/science.1217138.

- ↑ Rajbhandary, U. L. (2011). "Har Gobind Khorana (1922–2011)". Nature. 480 (7377): 322. doi:10.1038/480322a.

- ↑ "The Official Site of Louisa Gross Horwitz Prize".

- ↑ Thomas P. Sakmar (2012). "Har Gobind Khorana (1922–2011): Pioneering Spirit". PLoS Biology. 10 (2). doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001273.

- ↑ "HG Khorana Britannica".

- 1 2 "Biochemist Har Gobind Khorana, whose UW work earned the Nobel Prize, dies". news.wisc.edu. Retrieved 2017-01-10.

- ↑ Kresge, Nicole; Simoni, Robert D.; Hill, Robert L. (2009-05-29). "Total Synthesis of a Tyrosine Suppressor tRNA: the Work of H. Gobind Khorana". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 284 (22): e5. ISSN 0021-9258. PMC 2685647

.

. - ↑ "MIT HG Khorana MIT laboratory".

- 1 2 "HG Khorana Nobel Lecture".

- 1 2 Khorana, H. G. (1979). "Total synthesis of a gene". Science. 203 (4381): 614–625. PMID 366749. doi:10.1126/science.366749.

- ↑ Kleppe, K.; Ohtsuka, E.; Kleppe, R.; Molineux, I.; Khorana, H. G. (1971). "Studies on polynucleotides *1, *2XCVI. Repair replication of short synthetic DNA's as catalyzed by DNA polymerases". Journal of Molecular Biology. 56 (2): 341–361. PMID 4927950. doi:10.1016/0022-2836(71)90469-4.

- ↑ Wildenauer, D.; Khorana, H. G. (1977). "The preparation of lipid-depleted bacteriorhodopsin". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 466 (2): 315–324. PMID 857886. doi:10.1016/0005-2736(77)90227-9.

- ↑ Ahuja, S.; Crocker, E.; Eilers, M.; Hornak, V.; Hirshfeld, A.; Ziliox, M.; Syrett, N.; Reeves, P. J.; Khorana, H. G.; Sheves, M.; Smith, S. O. (2009). "Location of the Retinal Chromophore in the Activated State of Rhodopsin*". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 284 (15): 10190–10201. PMC 2665073

. PMID 19176531. doi:10.1074/jbc.M805725200.

. PMID 19176531. doi:10.1074/jbc.M805725200. - ↑ "Gobind Khorana, MIT professor emeritus, dies at 89 – MIT News Office". Web.mit.edu. 7 November 2011. Retrieved 12 November 2011.

- ↑ Chandigarh mourns death of Nobel laureate Hargobind Khorana

External links

- The Khorana Program

- 33rd Steenbock Symposium

- Remembering Har Gobind Khorana: University of Wisconsin Biochemistry Newsletter, adapted from article in Cell

- Har Gobind Khorana materials in the South Asian American Digital Archive (SAADA)